Shifting Perspectives in the Venice Biennale's Hungarian Exhibition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ausstellungskalender

Zu loben ist, mit welch großer Genauigkeit sich Verf. des Kataloges angenommen, mit welcher Sorgfalt er jedes einzelne der Blätter geprüft hat, deren überraschend umfang reiche Zahl in den verschiedenen öffentlichen Sammlungen und im Privatbesitz mehr als 100 beträgt. Die auf Tafeln beigegebenen Abbildungen sind in der Auswahl als vor züglich zu bezeichnen. Leider sind die Zeichnungen alle in einem einheitlichen, rötlich braun getönten Offsetdruck wiedergegeben, selbst da, wo der Katalog z. B. grau laviert angibt, was häufig der Fall ist (vgl. dagegen die doch sehr gut auf Kunstdruck wiedergegebenen Taf. 66 u. 68!). Dem Verf. kommt das Verdienst zu, in dem vorliegen den repräsentativen Band einen wichtigen Beitrag zur Erforschung des südwestdeutschen Rokoko geleistet zu haben. Sein Werk ist außerdem ein wesentlicher Beitrag zur Kennt nis der deutschen Zeichnung im 18. Jahrhundert. Gerhard Woeckel PERSONALIA Der bisherige Konservator am Germanischen Nationalmuseum Dr. Peter Metz wurde mit Wirkung vom 1. Januar 1955 als Direktor der Skulpturen-Abteilung der Ehern. Staatl. Museen nach Berlin berufen. Der bisherige Leiter der Fürstl. Fürstenberg. Sammlungen Dr. Altgraf Salm ist mit der Gesamtleitung der Fürstl. Fürstenberg. Institute für Kunst und Wissenschaft be trautworden. GROSSE AUSSTELLUNGEN 1955 Venedig Palazzo Ducale. 25. 4.—23. 10. 1955: Giorgione e i Giorgioneschi. Paris Bibliotheque Nationale. Ab 15. 6. 1955: Les Manuscrits ä Peintures en France du XHIe au XVIe Siede. AUSSTELLUNGSKALENDER AACHEN Suermondt-Museum. Februar BREMEN Kunsthalle. Bis 20. 2. 1955: Zeit 1955: Gemälde von Günther Weißflog. Im graph. genössische Kunst des deutschen Ostens. Bis 27. 2. Kabinett: „Bilderbögen“ der Biedermeierzeit.1955: „Das Aquarell“. Meisterblätter a. d. Kupfer BASEL Galerie d’Art Moderne. -

1 Pavilion of Greece at the 58Th International Art Exhibition ― La

Press Release Pavilion of Greece at the 58th International Art Exhibition ― La Biennale di Venezia Artists Panos Charalambous, Eva Stefani, and Zafos Xagoraris represent Greece at the Biennale Arte 2019 in an exhibition titled Mr. Stigl curated by Katerina Tselou May 11–November 24, 2019 Pre-opening: May 8–10, 2019 Inauguration: May 10, 2019, 2 p.m. Giardini, Venice Artists Panos Charalambous, Eva Stefani, and Zafos Xagoraris represent Greece at the 58th International Art Exhibition―La Biennale di Venezia (May11–November 24, 2019) with new works and in situ installations, curated by Katerina Tselou. Lining the Greek Pavilion in Venice―both inside and outside―with installations, images, In the environment they create, there is an constant transposition occurring from grand narratives to personal stories. The unknown (or less known) details of history emerge, subverting Mr. Stigl, who lends his name to the title of the Greek Pavilion exhibition, is a historical paradox, a constructive misunderstanding, a fantastical hero of an unknown story whose poetics take us to a space of doubt, paraphrased sounds, and nonsensical identities and histories. What does history rewrite and what does it conceal? The voices introduced by Panos Charalambous reach us through the rich collection of vinyl records he has accumulated since the 1980s. By combining installations with sonic performances, Charalambous brings forward voices that have been forgotten or silenced, recomposing their orality through an idiosyncratic play of vinyl using eagle’s claws, rose thorns, and agave leaves. His new work An Eagle Was Standing drinking glasses upon which an ecstatic, “ultrasonic” dance is performed—a vortex of deep listening. -

MOMA Pavilion in Venice

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART 11 WEST 53 STREET, NEW YORK 19, N. Y FOR RELEASE: MONDAY, TELEPHONE: CIRCLE 5-8900 March 29, 19Si No. 32 MUSEUM OF MODERN ART BUYS EXHIBITION PAVILION IN VENICE William A.M. Burden, President of the Museum of Modern Art, announced today that the Museum has bought the pavilion used for showing modern American art at the Intel-national Art Biennale Exhibitions in Venice, The pavilion, formerly owned by the Grand Central Art Galleries of New York, is the only privately-owned exhibition hall at the famous international art show. The other pavilions are owned by more that 20 governments which officially sponsor exhibitions of contemporary art from their own countries at the Biennale, The Museum of Modern Art has bought the building, Mr* Burden said, in order to insure the continuous representation of art from this country at these famous inter national exhibitions which have been held every two years since 1892 except for the war period* The Venice Biennale is sponsored by the Italian government in order "to bring together some of the most noteworthy and significant examples of con temporary Italian and foreign art" according to the official prospectus, To present as broad a representation of American art as possible the Museum of Modern Art will ask other leading institutions in this country to co-operate in organizing future exhibitions. The exhibition hall in Venice was purchased to implement the Museum's Inter national Exhibitions Program, made possible by a grant to the Museum last year from the Rockefeller Brothers Fund. -

Venice & the Common Ground

COVER Magazine No 02 Venice & the Common Ground Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 01 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 01 of 02 EDITORIAL 04 STATEMENTS 25 - 29 EDITORIAL Re: COMMON GROUND Reflections and reactions on the main exhibition By Pedro Gadanho, Steven Holl, Andres Lepik, Beatrice Galilee a.o. VIDEO INTERVIew 06 REPORT 30 - 31 WHAT IS »COMMON GROUND«? THE GOLDEN LIONS David Chipperfield on his curatorial concept Who won what and why Text: Florian Heilmeyer Text: Jessica Bridger PHOTO ESSAY 07 - 21 INTERVIew 32 - 39 EXCAVATING THE COMMON GROUND STIMULATORS AND MODERATORS Our highlights from the two main exhibitions Jury member Kristin Feireiss about this year’s awards Interview: Florian Heilmeyer ESSAY 22 - 24 REVIEW 40 - 41 ARCHITECTURE OBSERVES ITSELF GUERILLA URBANISM David Chipperfield’s Biennale misses social and From ad-hoc to DIY in the US Pavilion political topics – and voices from outside Europe Text: Jessica Bridger Text: Florian Heilmeyer Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 02 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 02 of 02 ReVIEW 42 REVIEW 51 REDUCE REUSE RECYCLE AND NOW THE ENSEMBLE!!! Germany’s Pavilion dwells in re-uses the existing On Melancholy in the Swiss Pavilion Text: Rob Wilson Text: Rob Wilson ESSAY 43 - 46 ReVIEW 52 - 54 OLD BUILDINGS, New LIFE THE WAY OF ENTHUSIASTS On the theme of re-use and renovation across the An exhibition that’s worth the boat ride biennale Text: Elvia Wilk Text: Rob Wilson ReVIEW 47 ESSAY 55 - 60 CULTURE UNDER CONSTRUCTION DARK SIDE CLUB 2012 Mexico’s church pavilion The Dark Side of Debate Text: Rob Wilson Text: Norman Kietzman ESSAY 48 - 50 NEXT 61 ARCHITECTURE, WITH LOVE MANUELLE GAUTRAND Greece and Spain address economic turmoil Text: Jessica Bridger Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 03 EDITORIAL Inside uncube No.2 you’ll find our selections from the 13th Architecture Biennale in Venice. -

Venice's Giardini Della Biennale and the Geopolitics of Architecture

FOLKLORIC MODERNISM: VENICE’S GIARDINI DELLA BIENNALE AND THE GEOPOLITICS OF ARCHITECTURE Joel Robinson This paper considers the national pavilions of the Venice Biennale, the largest and longest running exposition of contemporary art. It begins with an investigation of the post-fascist landscape of Venice’s Giardini della Biennale, whose built environment continued to evolve in the decades after 1945 with the construction of several new pavilions. With a view to exploring the architectural infrastructure of an event that has always billed itself as ‘international’, the paper asks how the mapping of national pavilions in this context might have changed to reflect the supposedly post-colonial and democratic aspirations of the West after the Second World War. Homing in on the nations that gained representation here in the 1950s and 60s, it looks at three of the more interesting architectural additions to the gardens: the pavilions for Israel, Canada and Brazil. These raise questions about how national pavilions are mobilised ideologically, and form/provide the basis for a broader exploration of the geopolitical superstructure of the Biennale as an institution. Keywords: pavilion, Venice Biennale, modernism, nationalism, geopolitics, postcolonialist. Joel Robinson, The Open University Joel Robinson is a Research Affiliate in the Department of Art History at the Open University and an Associate Lecturer for the Open University in the East of England. His main interests are modern and contemporary art, architecture and landscape studies. He is the author of Life in Ruins: Architectural Culture and the Question of Death in the Twentieth Century (2007), which stemmed from his doctoral work in art history at the University of Essex, and he is co-editor of a new anthology in art history titled Art and Visual Culture: A Reader (2012). -

Network Venice Brochure

NETWORK 2020 “The Venice Architecture Biennale is the most important architectural show on earth.” Tristram Carfrae Deputy Chair, Arup NETWORK Join us on the journey to 2020 Support Australia in Venice and be a part of something big as we seek to advance architecture through international dialogue, answering the call – How will we live together?. Network, build connections and engage with the local and global architecture and design community and be recognised as a leader with acknowledgement of support throughout Australia’s marketing campaign and on the ground in Venice. Join Network Venice now and maximise your benefits with VIP attendance at the upcoming Creative Director Reveal events being held in Melbourne and Sydney this October. JOURNEY TO National and international and beyond media campaign commences Exhibition development October Creative Director 2019 Shortlist announced 2020 Creative Director Engagement announced at opportunities for a special event Network Venice for partners and supporters supporters VENICE 2020 How will we live together? “We need a new spatial contract. In the context of widening political divides and growing 275k + economic inequalities, we call on architects to Total Exhibition imagine spaces in which we can generously Visitors live together: together as human beings who, despite our increasing individuality, yearn to connect with one another and with other species across digital and real space; together as new households looking for more diverse 95k + and dignified spaces for inhabitation; together Australian -

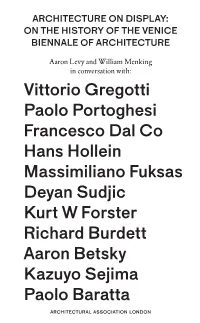

Architecture on Display: on the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture

archITECTURE ON DIspLAY: ON THE HISTORY OF THE VENICE BIENNALE OF archITECTURE Aaron Levy and William Menking in conversation with: Vittorio Gregotti Paolo Portoghesi Francesco Dal Co Hans Hollein Massimiliano Fuksas Deyan Sudjic Kurt W Forster Richard Burdett Aaron Betsky Kazuyo Sejima Paolo Baratta archITECTUraL assOCIATION LONDON ArchITECTURE ON DIspLAY Architecture on Display: On the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION LONDON Contents 7 Preface by Brett Steele 11 Introduction by Aaron Levy Interviews 21 Vittorio Gregotti 35 Paolo Portoghesi 49 Francesco Dal Co 65 Hans Hollein 79 Massimiliano Fuksas 93 Deyan Sudjic 105 Kurt W Forster 127 Richard Burdett 141 Aaron Betsky 165 Kazuyo Sejima 181 Paolo Baratta 203 Afterword by William Menking 5 Preface Brett Steele The Venice Biennale of Architecture is an integral part of contemporary architectural culture. And not only for its arrival, like clockwork, every 730 days (every other August) as the rolling index of curatorial (much more than material, social or spatial) instincts within the world of architecture. The biennale’s importance today lies in its vital dual presence as both register and infrastructure, recording the impulses that guide not only architec- ture but also the increasingly international audienc- es created by (and so often today, nearly subservient to) contemporary architectures of display. As the title of this elegant book suggests, ‘architecture on display’ is indeed the larger cultural condition serving as context for the popular success and 30- year evolution of this remarkable event. To look past its most prosaic features as an architectural gathering measured by crowd size and exhibitor prowess, the biennale has become something much more than merely a regularly scheduled (if at times unpredictably organised) survey of architectural experimentation: it is now the key global embodiment of the curatorial bias of not only contemporary culture but also architectural life, or at least of how we imagine, represent and display that life. -

This Book Is a Compendium of New Wave Posters. It Is Organized Around the Designers (At Last!)

“This book is a compendium of new wave posters. It is organized around the designers (at last!). It emphasizes the key contribution of Eastern Europe as well as Western Europe, and beyond. And it is a very timely volume, assembled with R|A|P’s usual flair, style and understanding.” –CHRISTOPHER FRAYLING, FROM THE INTRODUCTION 2 artbook.com French New Wave A Revolution in Design Edited by Tony Nourmand. Introduction by Christopher Frayling. The French New Wave of the 1950s and 1960s is one of the most important movements in the history of film. Its fresh energy and vision changed the cinematic landscape, and its style has had a seminal impact on pop culture. The poster artists tasked with selling these Nouvelle Vague films to the masses—in France and internationally—helped to create this style, and in so doing found themselves at the forefront of a revolution in art, graphic design and photography. French New Wave: A Revolution in Design celebrates explosive and groundbreaking poster art that accompanied French New Wave films like The 400 Blows (1959), Jules and Jim (1962) and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964). Featuring posters from over 20 countries, the imagery is accompanied by biographies on more than 100 artists, photographers and designers involved—the first time many of those responsible for promoting and portraying this movement have been properly recognized. This publication spotlights the poster designers who worked alongside directors, cinematographers and actors to define the look of the French New Wave. Artists presented in this volume include Jean-Michel Folon, Boris Grinsson, Waldemar Świerzy, Christian Broutin, Tomasz Rumiński, Hans Hillman, Georges Allard, René Ferracci, Bruno Rehak, Zdeněk Ziegler, Miroslav Vystrcil, Peter Strausfeld, Maciej Hibner, Andrzej Krajewski, Maciej Zbikowski, Josef Vylet’al, Sandro Simeoni, Averardo Ciriello, Marcello Colizzi and many more. -

1 Artist Portfolio This Document Includes

Artist Portfolio This document includes biographical information of the participating contribu- tors and abstracts of the planned projects (marked bold) for the biennial, com- piled by Asli Serbest and Mona Mahall, following conversations with the contrib- utors. 1 Artist Portfolio Mobile Albania Julia Blawert * 1983 in Offenburg, lives in Leipzig, works in Frankfurt/Main Till Korfhage * 1990 in Frankfurt/Main, lives in Halle, works in Frankfurt/Main Mobile Albania is a nomadic theatrical post state; its territories are temporary and its networks are analogue. Since 2009, it has traveled across Germany and the European continent, with different vehicles through different landscapes: cities, streets, rural areas. Mobile Albania is organized as an open collective with various artists, amateurs, and those that they collide with on the streets and in the cities. While being on the road Mobile Albania constantly develops new methodologies to start a dialogue with the surrounding, as a sort of a street university, as a communal space of artistic practices, knowledge exchange and production. Theater takes place that creates its contents on the street and from the encounter with passersby and residents. In Sinop, Mobile Albania will develop a mobile space where they adopt to the surrounding, interact with people and be tourists, but not regular ones: With the support of a wooden donkey they will find new ways to move around in the city. They will cross borders, fences, walls that normally tell us to stop. It is about bringing the way of wandering around in nature into the city and also to create news ways, to not always accept ready-made paths but to find their own ways. -

1910 Brussels International Exhibition

1910 Brussels International Exhibition Belgium’s 5th such event confirmed her position as a major host of international events. Staged thirteen years after the previous Brussels Expo (5 years after that in Liège), and a year after the London international exhibition at which Belgium had a large pavilion, this fair revealed the government’s heavy commitment to international display. King Albert was patron and le Comte de Smet de Naeyer, minister of finance and public works, oversaw his department’s involvement in its construction. Major participants were France, Holland, UK & Ireland, Russia, Germany, Brazil, Spain & Italy. A pavilion for all other nations was erected, in which they put up stands. In all fewer nations attended than previous exhibitions. The exhibition opened on 23 April and closed during November. Some 13,000,000 people attended but the fair lost some 10,000 BEF. About 9 pm on the evening of Sunday 14 August, a fire broke out, but apart from the animals in the zoo being killed by smoke and heat, nobody was killed, as the public had already gone home. The fire broke out near the central gallery and quickly spread to the British section, the city of Paris pavilion and a French restaurant. After several hours the fire was brought under control, the rest of the site escaping damage. The remaining British industrial exhibits were relocated in the Salle des Fêtes. The fire greatly stimulated people’s curiosity to see the exhibition. The exhibition was sited in the Solbosch park, near the Bois de la Cambre at the outer end of the Avenue Louise in. -

Antonio Prieto; » Julio Aè Pared 30 a Craftsman5 Ipko^Otonmh^

Until you see and feel Troy Weaving Yarns . you'll find it hard to believe you can buy such quality, beauty and variety at such low prices. So please send for your sample collection today. and Textile Company $ 1.00 brings you a generous selection of the latest and loveliest Troy quality controlled yarns. You'll find new 603 Mineral Spring Avenue, Pawtucket, R. I. 02860 pleasure and achieve more beautiful results when you weave with Troy yarns. »««Él Mm m^mmrn IS Dialogue .n a « 23 Antonio Prieto; » Julio Aè Pared 30 A Craftsman5 ipKO^OtONMH^ IS«« MI 5-up^jf à^stoneware "iactogram" vv.i is a pòìnt of discussion in Fred-Schwartz's &. Countercues A SHOPPING CENTER FOR JEWELRY CRAFTSMEN at your fingertips! complete catalog of... TOOLS AND SUPPLIES We've spent one year working, compiling and publishing our new 244-page Catalog 1065 ... now it is available. In the fall of 1965, the Poor People's Corporation, a project of the We're mighty proud of this new one... because we've incor- SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee), sought skilled porated brand new never-before sections on casting equipment, volunteer craftsmen for training programs in the South. At that electroplating equipment and precious metals... time, the idea behind the program was to train local people so that they could organize cooperative workshops or industries that We spent literally months redesigning the metals section . would help give them economic self-sufficiency. giving it clarity ... yet making it concise and with lots of Today, PPC provides financial and technical assistance to fifteen information.. -

56Th Venice Biennale—Main Exhibition, National Pavilions, Off-Site and Museums

56th Venice Biennale—Main exhibition, National Pavilions, Off-Site and Museums by Chris Sharp May 2015 Adrian Ghenie, Darwin and the Satyr, 2014. Okay, in the event that you, dear reader(s), are not too tired of the harried Venice musings of the art-agenda corps rearing up in your inbox, here’s a final reflection. Allow me to start with an offensively obvious observation. In case you haven’t noticed, Venice is not particularly adapted to the presentation of contemporary art. In fact, this singular city is probably the least appropriate place to show contemporary art, or art of any kind, and this is from a totally practical point of view. From the aquatic transportation of works to questions of humidity to outmoded issues of national representation, Venice is not merely an anachronism but also, and perhaps more importantly, a point of extravagance without parallel in the global art-circuit calendar. When you learn how much it costs to get on the map even as a collateral event, you understand that the sheer mobilization of monies and resources that attends this multifarious, biannual event is categorically staggering. This mobilization is far from limited to communication as well as the production and transportation of art, but also includes lodging, dinners, and parties. For example, the night of my arrival, I found myself at a dinner for 400 people in a fourteenth-century palazzo. Given in honor of one artist, it was bankrolled by her four extremely powerful galleries, who, if they want to remain her galleries and stay in the highest echelons of commercial power, must massively throw down for this colossal repast and subsequent party, on top of already, no doubt, jointly co-funding the production of her pavilion, while, incidentally, co-funding other dinners, parties, and so on and so forth.