Renato Guttuso's Boogie Woogie in Rome (1953): a Geopolitical Tableau

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Venice & the Common Ground

COVER Magazine No 02 Venice & the Common Ground Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 01 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 01 of 02 EDITORIAL 04 STATEMENTS 25 - 29 EDITORIAL Re: COMMON GROUND Reflections and reactions on the main exhibition By Pedro Gadanho, Steven Holl, Andres Lepik, Beatrice Galilee a.o. VIDEO INTERVIew 06 REPORT 30 - 31 WHAT IS »COMMON GROUND«? THE GOLDEN LIONS David Chipperfield on his curatorial concept Who won what and why Text: Florian Heilmeyer Text: Jessica Bridger PHOTO ESSAY 07 - 21 INTERVIew 32 - 39 EXCAVATING THE COMMON GROUND STIMULATORS AND MODERATORS Our highlights from the two main exhibitions Jury member Kristin Feireiss about this year’s awards Interview: Florian Heilmeyer ESSAY 22 - 24 REVIEW 40 - 41 ARCHITECTURE OBSERVES ITSELF GUERILLA URBANISM David Chipperfield’s Biennale misses social and From ad-hoc to DIY in the US Pavilion political topics – and voices from outside Europe Text: Jessica Bridger Text: Florian Heilmeyer Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 02 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 02 of 02 ReVIEW 42 REVIEW 51 REDUCE REUSE RECYCLE AND NOW THE ENSEMBLE!!! Germany’s Pavilion dwells in re-uses the existing On Melancholy in the Swiss Pavilion Text: Rob Wilson Text: Rob Wilson ESSAY 43 - 46 ReVIEW 52 - 54 OLD BUILDINGS, New LIFE THE WAY OF ENTHUSIASTS On the theme of re-use and renovation across the An exhibition that’s worth the boat ride biennale Text: Elvia Wilk Text: Rob Wilson ReVIEW 47 ESSAY 55 - 60 CULTURE UNDER CONSTRUCTION DARK SIDE CLUB 2012 Mexico’s church pavilion The Dark Side of Debate Text: Rob Wilson Text: Norman Kietzman ESSAY 48 - 50 NEXT 61 ARCHITECTURE, WITH LOVE MANUELLE GAUTRAND Greece and Spain address economic turmoil Text: Jessica Bridger Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 03 EDITORIAL Inside uncube No.2 you’ll find our selections from the 13th Architecture Biennale in Venice. -

The Role of Literature in the Films of Luchino Visconti

From Page to Screen: the Role of Literature in the Films of Luchino Visconti Lucia Di Rosa A thesis submitted in confomity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph. D.) Graduate Department of ltalian Studies University of Toronto @ Copyright by Lucia Di Rosa 2001 National Library Biblioth ue nationale du Cana2 a AcquisitTons and Acquisitions ef Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 WeOingtOn Street 305, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Otiawa ON K1AW Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence ailowing the exclusive ~~mnettantà la Natiofliil Library of Canarla to Bibliothèque nation& du Canada de reprcduce, loan, disûi'bute or seil reproduire, prêter, dishibuer ou copies of this thesis in rnicroform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format é1ectronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation, From Page to Screen: the Role of Literatuce in the Films af Luchino Vionti By Lucia Di Rosa Ph.D., 2001 Department of Mian Studies University of Toronto Abstract This dissertation focuses on the role that literature plays in the cinema of Luchino Visconti. The Milanese director baseci nine of his fourteen feature films on literary works. -

Venice's Giardini Della Biennale and the Geopolitics of Architecture

FOLKLORIC MODERNISM: VENICE’S GIARDINI DELLA BIENNALE AND THE GEOPOLITICS OF ARCHITECTURE Joel Robinson This paper considers the national pavilions of the Venice Biennale, the largest and longest running exposition of contemporary art. It begins with an investigation of the post-fascist landscape of Venice’s Giardini della Biennale, whose built environment continued to evolve in the decades after 1945 with the construction of several new pavilions. With a view to exploring the architectural infrastructure of an event that has always billed itself as ‘international’, the paper asks how the mapping of national pavilions in this context might have changed to reflect the supposedly post-colonial and democratic aspirations of the West after the Second World War. Homing in on the nations that gained representation here in the 1950s and 60s, it looks at three of the more interesting architectural additions to the gardens: the pavilions for Israel, Canada and Brazil. These raise questions about how national pavilions are mobilised ideologically, and form/provide the basis for a broader exploration of the geopolitical superstructure of the Biennale as an institution. Keywords: pavilion, Venice Biennale, modernism, nationalism, geopolitics, postcolonialist. Joel Robinson, The Open University Joel Robinson is a Research Affiliate in the Department of Art History at the Open University and an Associate Lecturer for the Open University in the East of England. His main interests are modern and contemporary art, architecture and landscape studies. He is the author of Life in Ruins: Architectural Culture and the Question of Death in the Twentieth Century (2007), which stemmed from his doctoral work in art history at the University of Essex, and he is co-editor of a new anthology in art history titled Art and Visual Culture: A Reader (2012). -

Militante. Enrico Crispolti E Il Suo Archivio

LA VERTIGINE DELL’ARCHIVIO - https://teca.unibo.it LUCA PIETRO NICOLETTI Un ‘cantiere’ militante. Enrico Crispolti e il suo archivio ABSTRACT The paper is about the archive of Enrico Crispolti (Roma 1933-2018), art critic and contemporary art historian, and about his militant idea of ‘dynamic’ archive and the methodological consequences: the researcher witch study contemporary art often is the ‘inventor’ of future archival source. KEYWORDS: Militant critic; History of contemporary art; Critical blockbuster notes; Correspondence; Rome. L’intervento si concentra sull’archivio del critico d’arte Enrico Crispolti (Roma 1933-2018), e soprattutto l’evoluzione di un’idea ‘militante’ di archivio ‘attivo’, con le sue conseguenze sul piano metodologico: lo storico dell’arte contemporanea, spesso, contribuisce alla creazione delle fonti d’archivio sui temi che costituiscono oggetto del suo studio. PAROLE CHIAVE: Critica militante; Storia dell’arte contemporanea; Taccuino critico; Carteggio; Roma. DOI: https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.2240-3604/11684 _______________________________________ rispolti, ricordava Enrico Baj nel 1983 nella sua Automitobiografia, entrò in contatto con me verso la fine del 1957 […]: gli mandai inoltre dei gran pacchi di documenti che lo resero felice. Crispolti infatti è una macchina raccoglitrice e nei suoi archivi trovi di tutto: anche quello che tu, che ne sei l’autore, non hai. […] Poi, a partire dal 1970, compilava per l’editore Bolaffi di Torino il catalogo generale delle mie opere, catalogo che vedeva la luce nell’ottobre del 1973 e che comprendeva tutti i miei quadri sino al Pinelli incluso. Fu appunto nella stesura critica e documentale di detta opera che la vastità e la varietà dell’informazione crispoltiana eccelse incontrastata. -

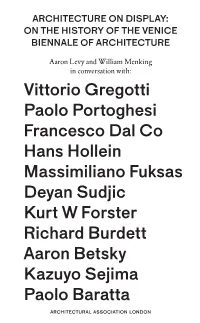

Architecture on Display: on the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture

archITECTURE ON DIspLAY: ON THE HISTORY OF THE VENICE BIENNALE OF archITECTURE Aaron Levy and William Menking in conversation with: Vittorio Gregotti Paolo Portoghesi Francesco Dal Co Hans Hollein Massimiliano Fuksas Deyan Sudjic Kurt W Forster Richard Burdett Aaron Betsky Kazuyo Sejima Paolo Baratta archITECTUraL assOCIATION LONDON ArchITECTURE ON DIspLAY Architecture on Display: On the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION LONDON Contents 7 Preface by Brett Steele 11 Introduction by Aaron Levy Interviews 21 Vittorio Gregotti 35 Paolo Portoghesi 49 Francesco Dal Co 65 Hans Hollein 79 Massimiliano Fuksas 93 Deyan Sudjic 105 Kurt W Forster 127 Richard Burdett 141 Aaron Betsky 165 Kazuyo Sejima 181 Paolo Baratta 203 Afterword by William Menking 5 Preface Brett Steele The Venice Biennale of Architecture is an integral part of contemporary architectural culture. And not only for its arrival, like clockwork, every 730 days (every other August) as the rolling index of curatorial (much more than material, social or spatial) instincts within the world of architecture. The biennale’s importance today lies in its vital dual presence as both register and infrastructure, recording the impulses that guide not only architec- ture but also the increasingly international audienc- es created by (and so often today, nearly subservient to) contemporary architectures of display. As the title of this elegant book suggests, ‘architecture on display’ is indeed the larger cultural condition serving as context for the popular success and 30- year evolution of this remarkable event. To look past its most prosaic features as an architectural gathering measured by crowd size and exhibitor prowess, the biennale has become something much more than merely a regularly scheduled (if at times unpredictably organised) survey of architectural experimentation: it is now the key global embodiment of the curatorial bias of not only contemporary culture but also architectural life, or at least of how we imagine, represent and display that life. -

Villa Wolkonsky Leonardo in Milan the Renzi Government Guttuso at the Estorick Baron Corvo in Venice

Villa Wolkonsky Leonardo in Milan The Renzi Government Guttuso at the Estorick RIVISTA Baron Corvo in Venice 2015-2016 The Magazine of Dear readers o sooner had we consigned our first Rivista to the in their city. We hope that you too will make some printers, than it was time to start all over again. discoveries of your own as you make your way through the NStaring at a blank piece of paper, or more accurately pages that follow. an empty screen and wondering where the contributions We are most grateful for the positive feedback we received are going to come from is a daunting prospect. But slowly from readers last year and hope that this, our second issue, the magazine began to take shape; one or two chance will not disappoint. encounters produced interesting suggestions on subjects Buona lettura! we knew little or nothing about and ideas for other features developed from discussion between ourselves and British Linda Northern and Vanessa Hall-Smith Italian Society members. Thank you to all our contributors. And as the contributions began to arrive we found some unlikely connections – the Laocoon sculpture, the subject of an excellent talk which you can read about in the section dedicated to the BIS year, made a surprise appearance in a feature about translation. The Sicilian artist, Renato Guttoso, an exhibition of whose work is reviewed on page 21, was revealed as having painted Ian Greenlees, a former director of the British Institute of Florence, whose biography is considered at page 24. We also made some interesting discoveries, for example that Laura Bassi, an 18th century mathematician and physicist from Bologna, was highly regarded by no less a figure than Voltaire and that the Milanese delight in finding unusual nicknames for landmarks Vanessa Hall-Smith Linda Northern Cover photo: Bastoni in a Sicilian pack of cards. -

Export / Import: the Promotion of Contemporary Italian Art in the United States, 1935–1969

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2016 Export / Import: The Promotion of Contemporary Italian Art in the United States, 1935–1969 Raffaele Bedarida Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/736 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] EXPORT / IMPORT: THE PROMOTION OF CONTEMPORARY ITALIAN ART IN THE UNITED STATES, 1935-1969 by RAFFAELE BEDARIDA A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 RAFFAELE BEDARIDA All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the Dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ___________________________________________________________ Date Professor Emily Braun Chair of Examining Committee ___________________________________________________________ Date Professor Rachel Kousser Executive Officer ________________________________ Professor Romy Golan ________________________________ Professor Antonella Pelizzari ________________________________ Professor Lucia Re THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT EXPORT / IMPORT: THE PROMOTION OF CONTEMPORARY ITALIAN ART IN THE UNITED STATES, 1935-1969 by Raffaele Bedarida Advisor: Professor Emily Braun Export / Import examines the exportation of contemporary Italian art to the United States from 1935 to 1969 and how it refashioned Italian national identity in the process. -

58TH VENICE ART BIENNALE By

73 / JULY / AUGUST / SEPTEMBER 2019 1 JULY — AUGUST — SEPTEMBER 2019 / OFFICE OF DISPOSAL 9000 GENT X - P509314 - X GENT 9000 DISPOSAL OF OFFICE / 2019 SEPTEMBER — AUGUST — JULY 20 58TH VENICE ART BIENNALE by DOMINIQUE MOULIN CULTURAL COMMENTS COMMENTS CULTURAL Too real to be surreal 2019 Deep See Blue Surrounding You, , s Laure Prouvo 20 21 58TH VENICE ART BIENNALE Dominique Moulin It goes without saying that the Venice COMMENTS CULTURAL Art Biennale divides opinion, for that is the very nature of the sometimes-beautiful beast. The 58th edition was entrusted to the American curator Ralph Rugoff and his headline theme, May You Live In Interesting Times, appears a warning to appreciate the world as it is by observing it. And given Rugoff’s decision to only feature living artists, what we end up with are observers of our time. Jumping around the locations, DAMN°’s man on the ground gives his own point of view on the points of view on show. To live in the present time, as Ralph spectra III in the Central Pavilion. It put on a VR headset. For the next Rugoff – whose day job is director is a corridor whose white light daz- eight minutes we are immersed in of London’s Hayward Gallery – en- zles us so much that we protect our- a universe in a gaseous state, with- courages us to do, is also to accept selves with our hands, as though not out any gravity or apparent limits, extreme complexity. And that may to observe the unobservable. This until we realise that we can act on be the reason why he asked Lara excess might suggest the mass of its form with movement – uncon- Favaretto to plunge the Central Pa- information that daily overwhelms scious at first – of the head. -

La Città Dell' Uomo

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Archivio istituzionale della ricerca - Politecnico di Milano A € 25,00 / B € 21,00 / CH CHF 20,00 Poste Italiane S.p.A. aprile/april euro 10.00 Italy only CH Canton Ticino CHF 20,00 / D € 26,00 Spedizione in Abbonamento Postale D.L. 353/2003 periodico mensile E € 19,95 / F € 16,00 / I € 10,00 / J ¥ 3,100 (conv. in Legge 27/02/2004 n. 46), Articolo 1, 2017 d. usc. 01/04/17 NL € 16,50 / P € 19,00 / UK £ 18,20 / USA $ 33,95 Comma 1, DCB—Milano 1012 LA CITTÀ DELL’ UOMO domus 1012 Aprile / April 2017 SOMMARIO/CONTENTS IX Autore / Author Progettista / Designer Titolo Title Nicola Di Battista X Editoriale Editorial Del mestiere On our profession Coriandoli Confetti Ross Lovegrove 1 Scultura e tecnologia Sculpture and technology Christian Kerez 6 Laboratorio Burda The Burda workshop Smiljan Radic Franco Marrocco 10 Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera, Milano Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera, Milan Predrag Matvejevic´ 16 Sull’Adriatico The Adriatic Collaboratori / Lorenzo Pignatti 20 Un ricordo di Predrag Matvejevic´ Remembering Predrag Matvejevic´ Consultants Cristina Moro Guido Musante Emanuele Orsini 21 Fare sistema e ascoltare tutti i territori d’Italia Create a system and listen to all areas of Italy Traduttori / Translators Beppe Finessi 24 SaloneSatellite. 20 anni di nuova creatività SaloneSatellite. 20 years of new creativity Paolo Cecchetto Daniel Clarke Achille Bonito Oliva 30 Totò e l’arte contemporanea Totò and contemporary art Barbara Fisher Ferdinando -

Polish Pavilion at the 58Th International Art Exhibition — La Biennale Di Venezia Venice, 11 May–24 November 2019

Polish Pavilion at the 58th International Art Exhibition — La Biennale di Venezia Venice, 11 May–24 November 2019 FLIGHT artist: Roman Stańczak curators: Łukasz Mojsak, Łukasz Ronduda representative of the Zachęta: Ewa Mielczarek commissioner of the Polish Pavilion: Hanna Wróblewska organiser: Zachęta — National Gallery of Art Please feel invited to explore the texts accompanying the exhibition at the Polish Pavilion: curatorial statement by Łukasz Mojsak and Łukasz Ronduda, excerpt from text by Andrzej Szczerski concerning the Flight project, text by Dorota Michalska devoted to the artistic practice of Roman Stańczak, and essay by Adam Szymczyk devoted to the idea of the Biennale and national pavilions. Łukasz Mojsak, Łukasz Ronduda Two Aircrafts Imagining the outcome of the process, initiated by Roman Stańczak, of turning an aircraft inside out posed considerable difficulties. Based on a seemingly straightforward transformation algorithm, the artist’s concept was challenging, if not downright impossible, to visualise. Stańczak himself declared that for him the final result was shrouded in mystery. Thus, from the very beginning, Flight has borne characteristics of an artwork that seeks to convey an unimaginable situation — one that needs to be ex- perienced in order to make any attempts at understanding possible at all. Stańczak’s inside-out aircraft is a piece devoted to unimaginable reversals, extremely rare and often inexplicable events, paradoxes and shocks that shape history and determine the modern-day condition of Europe and the world. It is a monument to the obverses and reverses of reality, which — however difficult it is to imagine — pene- trate each other or unexpectedly swap places. -

Pizzinato.Pdf

CENTRO INTERUNIVERSITARIO DI STUDI VENETI * BIBLIOTECA VENETA CARTE DEL CONTEMPORANEO a cura di silvana tamiozzo goldmann 3 Con « Carte del Contemporaneo » si inaugura, per il Centro Interuniversitario di Studi Veneti, una nuova stagione. « Biblioteca veneta » si trasforma: non piú (non soltanto) collezione di edizioni e di ricerche letterarie e filologiche, ma sistema ar- ticolato dell’intera attività del CISVe. Sotto la sua ombra protettiva si vogliono svi- luppare, in forma di collane, progetti editoriali dedicati ad ambiti diversi ma tutti ancorati alla storia e alla cultura delle Venezie: oltre agli studi sulla testualità lette- raria Antico Regime e moderna (terreno abituale degli studiosi che finora hanno alimentato il palchetto della nostra collezione), la ricerca sulla letteratura contem- poranea, sui fondi librari (manoscritti e a stampa), sulle fonti d’archivio, sulla storia linguistica e socio-culturale. «Carte del Contemporaneo » è la prima di queste collane, dedicata alla ricerca sulla cultura del Novecento veneto, vista attraverso una lente particolare, i docu- menti d’archivio; essa nasce innanzitutto come estensione editoriale dell’Archivio omonimo, creato per impulso di Silvana Tamiozzo Goldmann e di Francesco Bru- ni, e ospitato nella sede del CISVe, dove oggi sono conservati, per la comunità degli studiosi, i fondi Ernesto Calzavara, Pier Maria Pasinetti, Armando Pizzinato, Carlo Della Corte. La collana intende essere il luogo in cui filologia materiale, critica genetica e ana- lisi letteraria possano agire perché le pratiche della catalogazione e della conserva- zione dei beni d’archivio siano anche il lievito vitale della ricezione critica di testi e autori; essa ospiterà quindi edizioni di inediti e di epistolari, studi filologici e critici, repertori catalografici, che abbiano come oggetto le carte inedite depositate nel- l’Archivio, e come fine la loro interpretazione e valorizzazione. -

10 Pittori E 10 Incisori Trentini Del XX Secolo

10 pittori e 10 incisori trentini del XX secolo : problematica artistica di 3 generazioni : Roma, Palazzo delle Esposizioni, giugno-luglio 1971 : Trento, Palazzo Pretorio, settembre-ottobre 1971 / Comitato trentino per la diffusione della cultura. - Roma : Arti grafiche Privitera, [1971?]. - [19], 111 p. : ill. ; 24 cm. 100 opere di van Dyck : catalogo della mostra : Genova Palazzo dell'Accademia, giugno-agosto 1955. - Genova : AGIS, 1955. - 54 p., [50] c. di tav. ; 24 cm. 105 opere di Antonio Mancini : mostra commemorativa sotto gli auspici della Reale Accademia d'Italia nel decennale della morte : marzo 1940-18. - [S.l. : s.n.], 1940 (Torino : Società editrice Torinese). - 27 p., [30] c. di tav. ; 25 cm. In testa al front.: Mostre d'arte della Gazzetta del Popolo. - Catalogo della mostra tenuta a Torino nel 1940. 300 dipinti di maestri contemporanei in vendita : esposizione dal 14 al 22 marzo, asta, 23-24-25 marzo alla Brera Galleria d'arte, Milano. - Milano : Galleria Centro Brera, 1964. - [68] c. : in gran parte ill ; 24 cm. Catalogo della mostra. 300 dipinti di maestri contemporanei in vendita : esposizione dal 23 al 31 marzo, asta, 1-2-3 aprile alla Brera Galleria d'arte, Milano. - Milano : Brera Galleria d'arte, 1963. - [69] c. : ill. ; 24 cm. Catalogo della mostra. 300 dipinti di maestri contemporanei in vendita : esposizione dall'1 al 9 giugno 1963, asta, 10-11-12 giugno alla Brera Galleria d'arte. - Milano : Brera Galleria d'arte, 1963. - [54] c. : in gran parte ill. ; 24 cm. Catalogo della mostra. 300 dipinti e disegni di maestri contemporanei in vendita : esposizione dal 10 al 25 marzo, asta, 26-27-28 marzo alla Brera Galleria d'arte, Milano.