TRANSFORMATIONS Comparative Study of Social Transformations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central Europe

Central Europe West Germany FOREIGN POLICY wTHEN CHANCELLOR Ludwig Erhard's coalition government sud- denly collapsed in October 1966, none of the Federal Republic's major for- eign policy goals, such as the reunification of Germany and the improvement of relations with its Eastern neighbors, with France, NATO, the Arab coun- tries, and with the new African nations had as yet been achieved. Relations with the United States What actually brought the political and economic crisis into the open and hastened Erhard's downfall was that he returned empty-handed from his Sep- tember visit to President Lyndon B. Johnson. Erhard appealed to Johnson for an extension of the date when payment of $3 billion was due for military equipment which West Germany had bought from the United States to bal- ance dollar expenses for keeping American troops in West Germany. (By the end of 1966, Germany paid DM2.9 billion of the total DM5.4 billion, provided in the agreements between the United States government and the Germans late in 1965. The remaining DM2.5 billion were to be paid in 1967.) During these talks Erhard also expressed his government's wish that American troops in West Germany remain at their present strength. Al- though Erhard's reception in Washington and Texas was friendly, he gained no major concessions. Late in October the United States and the United Kingdom began talks with the Federal Republic on major economic and military problems. Relations with France When Erhard visited France in February, President Charles de Gaulle gave reassurances that France would not recognize the East German regime, that he would advocate the cause of Germany in Moscow, and that he would 349 350 / AMERICAN JEWISH YEAR BOOK, 1967 approve intensified political and cultural cooperation between the six Com- mon Market powers—France, Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. -

Bbm:978-3-322-95484-8/1.Pdf

Anmerkungen Vgl. hierzu: Winfried Steffani, Monistische oder pluralistische Demokratie?, in: Günter Doeker, Winfried Steffani (Hrsg.), Klassenjustiz und Pluralismus. Festschrift ftir Ernst Fraenkel, Ham burg 1973, S. 482-514, insb. S. 503. 2 Da es im folgenden um die Untersuchung eines speziellen Ausschnittes des bundesdeutschen Regierungssystems geht, kann unter dem Aspekt arbeitsteiliger Wissenschaft auf die Entwick lung eines eigenständigen ausgewiesenen Konzepts parlamentarischer Herrschaft verzichtet werden. Grundlegend ftir diese Untersuchung ist die von Winfried Steffani entwickelte Parla mentarismustheorie, vgl. zuletzt: ders., Parlamentarische und präsidentielle Demokratie, Opla den 1979, S. 160-163. 3 Steffani, Parlamentarische und präsidenticlle Demokratie, a.a.O., S. 92f. 4 Theodor Eschenburg, Zur politischen Praxis in der Bundesrepublik, Bd. 1, 2. überarbeitete und mit Nachträgen versehene Auflage, München 1967, Vorwort, S. 10. 5 Zur Bedeutung des Amtsgedankens für die politische Theorie vgl. Wilhelm Hennis, Amtsgedanke und Demokratiebegriff, in: ders., Die mißverstandene Demokratie, Freiburg im Breisgau 1973, S.9-25. 6 Ein Amtseid für Parlamentspräsidenten, so wie er von Wolfgang Härth gefordert wird, würde dieser Verpflichtung des Bundestagspräsidenten öffentlichen Ausdruck verleihen und sie damit zusätzlich unterstreichen. Eine Vereidigung des Bundestagspräsidenten wäre schon allein aus diesem Grunde sinnvoll und erforderlich. Vgl. Wolfgang Härth, Parlamentspräsidenten und Amtseid, in: Zeitschrift ftir Parlamentsfragen, Jg. 11 (1980), S. 497·503. 7 Vgl. Aristoteles, Nikomachische Ethik, übersetzt und herausgegeben von Franz Dirlmeier, 5. Aufl. Berlin (Akademie-Verlag) 1969, 1094b (S. 6f): "Die Darlegung wird dann befriedigen, wenn sie jenen Klarheitsgrad erreicht, den der gegebene Stoff gestattet. Der Exaktheitsanspruch darf nämlich nicht bei allen wissenschaftlichen Problemen in gleicher Weise erhoben werden " 8 Vgl. als Kritik aus neuerer Zeit z. -

Mitteilungen Für Die Presse

Read the speech online: www.bundespraesident.de Page 1 of 6 Federal President Frank-Walter Steinmeier at the inauguration of the Robert-Blum-Saal with artworks depicting Germany’s history of democracy at Schloss Bellevue on 9 November 2020 According to legend, the last words of Robert Blum were “I die for freedom, may my country remember me.” He was executed – shot – by imperial military forces on 9 November 1848, one day before his 41st birthday. The German democrat and champion for freedom, one of the most well-known members of the Frankfurt National Assembly, thus died on a heap of sand in Brigittenau, a Viennese suburb. The bullets ended the life of a man who had fought tirelessly for a Germany unified in justice and in freedom – as a political publicist, publisher and founder of the Schillerverein in Leipzig, as a parliamentarian in the Paulskirche in Frankfurt, and finally with a gun in his hand on the barricades in Vienna. To the very last, Robert Blum fought for a German nation-state in the republican mould, legitimised by parliamentary structures. He campaigned for a brand of democracy in which civil liberties and human rights were accorded to one and all. And he fought for a Europe in which free peoples should live together in peace, from France to Poland and to Hungary. His death on 9 November 1848 marked one of the many turning points in our history. By executing the parliamentarian Robert Blum, the princes and military commanders of the Ancien Régime demonstrated their power and sent an unequivocal message to the Paulskirche National Assembly. -

The German Fear of Russia Russia and Its Place Within German History

The German Fear of Russia Russia and its place within German History By Rob Dumont An Honours Thesis submitted to the History Department of the University of Lethbridge in partial fulfillment of the requirements for History 4995 The University of Lethbridge April 2013 Table of Contents Introduction 1-7 Chapter 1 8-26 Chapter 2 27-37 Chapter 3 38-51 Chapter 4 39- 68 Conclusion 69-70 Bibliography 71-75 Introduction In Mein Kampf, Hitler reflects upon the perceived failure of German foreign policy regarding Russia before 1918. He argues that Germany ultimately had to prepare for a final all- out war of extermination against Russia if Germany was to survive as a nation. Hitler claimed that German survival depended on its ability to resist the massive faceless hordes against Germany that had been created and projected by Frederick the Great and his successors.1 He contends that Russia was Germany’s chief rival in Europe and that there had to be a final showdown between them if Germany was to become a great power.2 Hitler claimed that this showdown had to take place as Russia was becoming the center of Marxism due to the October Revolution and the founding of the Soviet Union. He stated that Russia was seeking to destroy the German state by launching a general attack on it and German culture through the introduction of Leninist principles to the German population. Hitler declared that this infiltration of Leninist principles from Russia was a disease and form of decay. Due to these principles, the German people had abandoned the wisdom and actions of Frederick the Great, which was slowly destroying German art and culture.3 Finally, beyond this expression of fear, Hitler advocated that Russia represented the only area in Europe open to German expansion.4 This would later form the basis for Operation Barbarossa and the German invasion of Russia in 1941 in which Germany entered into its final conflict with Russia, conquering most of European 1 Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, trans Ralph Manheim (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1943, originally published 1926), 197. -

Erdverbunden Und Einfallsreich Lebenserinnerungen Des Sozialdemokraten Hans „Lumpi“ Lemp

Erdverbunden und einfallsreich Lebenserinnerungen des Sozialdemokraten Hans „Lumpi“ Lemp Lebenserinnerungen des Sozialdemokraten Hans „Lumpi“ Lemp ISBN 978-3-95861-499-4 Reihe Gesprächskreis Geschichte ISSN 0941-6862 und einfallsreich Erdverbunden Heft 106 Erdverbunden und einfallsreich Lebenserinnerungen des Sozialdemokraten Hans „Lumpi“ Lemp Gesprächskreis Geschichte Heft 106 Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Archiv der sozialen Demokratie GESPRÄCHSKREIS GESCHICHTE | HEFT 106 Herausgegeben von Anja Kruke und Meik Woyke Archiv der sozialen Demokratie Kostenloser Bezug beim Archiv der sozialen Demokratie der Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Email: [email protected] <http://library.fes.de/history/pub-history.html> © 2017 by Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Bonn Eine gewerbliche Nutzung der von der Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung herausgegebenen Medien ist ohne schriftliche Zustimmung der Herausgeberin nicht gestattet. Redaktion: Jens Hettmann, Patrick Böhm unter Mitarbeit von Helmut Herles Gestaltung und Satz: PAPYRUS – Lektorat + Textdesign, Buxtehude Umschlag: Pellens Kommunikationsdesign GmbH Druck: bub Bonner Universitäts-Buchdruckerei Bildmaterial: Soweit nicht anders vermerkt, stammen die hier verwendeten Fotos aus dem Familienbesitz Lemp; die Coverabbildung und die Abbildung auf S. 40 wurden uns von Volker Ernsting freundlicherweise kostenlos zur Verfügung gestellt; das Foto auf S. 22 haben wir unentgelt- lich von der Rechteinhaberin Nordphoto Vechta (Ferdinand Kokenge) erhalten. Eventuelle Rechte weiterer Dritter konnten nicht ermittelt werden. Für aufklärende -

Literaturverzeichnis

Literaturverzeichnis Jürgen Peter Schmied Sebastian Haffner Eine Biographie 683 Seiten, Gebunden ISBN: 978-3-406-60585-7 © Verlag C.H.Beck oHG, München Quellen- und Literaturverzeichnis I. Quellen A Ungedruckte Quellen 1. Akten Archiv der Humboldt Universität zu Berlin. Matrikelbuch, Rektorat, 600/116. Jur. Fak., Bd. 309. BBC Written Archive Centre, Reading. RCont 1, Sebastian Haffner File 1. Bundesarchiv. Personalakte Raimund Pretzel, R 3001, 71184. Personalakte Raimund Pretzel, ehemals BDC, RKK 2101, Box 0963, File 09. Bundesbehörde für die Unterlagen des Staatssicherheitsdienstes der ehemaligen Deutschen Demokratischen Republik, Berlin. ZA, MfS – HA IX/11. AF Pressemappe. ZA, MfS – HA IX/11. AF Z I, Bd. 3. ZA, MfS – HA IX/11. AF N-II, Bd. 1, Bd. 2. ZA, MfS – F 16/HVA. ZA, MfS – F 22/HVA. National Archives, Kew. FO 371/24424 FO 371/26554 FO 371/106085 HO 334/219 INF 1/119 KV 2/1129 KV 2/1130 PREM 11/3357 Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amtes, Berlin. B 8, Bd. 1498. B 11, Bd. 1019. 2 2. Nachlässe NL Konrad Adenauer Stiftung Bundeskanzler-Adenauer-Haus, Rhöndorf. NL Raymond Aron École des hautes études en sciences sociales, Paris. Centre de recherches politiques Raymond Aron. NL David Astor Privatbesitz. NL Margret Boveri Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Handschriftenabteilung. NL Willy Brandt Archiv der sozialen Demokratie. Friedrich-Ebert- Stiftung, Bonn. NL Eugen Brehm Institut für Zeitgeschichte, München. NL William Clark Bodleian Library, Oxford. Department of Special Col- lections and Western Manuscripts. NL Arthur Creech Jones Rhodes House Library, Oxford. NL Isaac Deutscher International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam. NL Sebastian Haffner Bundesarchiv. -

Information Issued by the Association of Jewish Refugees in Great Britain

Vol. XVIII No. 1 January, 1963 INFORMATION ISSUED BY THE ASSOCIATION OF JEWISH REFUGEES IN GREAT BRITAIN a FAIRFAX MANSIONS, FINCHLEY RD. (corner Fairfax Rd.), London, N.W.3 Off let and Consulting Houn: Telephone : MAIda Vale 9096.'7 (General Ofhce and Welfare for the Aged) Monday to Tluirsday 10 a.m.—1 p.m. 3—6 p.m. MAIda Vale 4449 (Employment Agency, annually licensed by the L.C.C.. and Social Services Dept.) fridaf 10 ajn.-1 p.m. Or. Rudolf R. Levy against any reference to international jurisdiction, and those who—as did Great Britain, France and Holland—sponsored the appeal to an ii}temational court, whether the Intemational Court of Justice PROTECTION AGAINST GROUP ATROCITIES or a special international high court for deating with acts of genocide. The latter took their stand on the fact that genocide could rarely be com The Genocide Convention mitted without the participation and tolerance of the State and therefore it would be, as the repre In connection with the neo-Nazi occurrences acceptance of rules applied first only among sentative of the Philippines formulated it, para Sir Barnett Janner, M.P., President of the Board of several nations and gradually becoming recognised doxical to leave punishment to the same State. Deputies, initiated a debate in the House of principles of international law." On the other hand, it may safely be assumed that Commons some time ago on the question of Great To avoid difficulties arising from the interpreta those who oppose international jurisdiction on Britain's accession to the Genocide Convention, tion of a general concept, a list of acts was given this matter would also not accept the jurisdiction the international agreement against group murder, in Article 2 which fall within the meaning of of a high court of this kind. -

01-026 Margot Kalinke

01-026 Margot Kalinke ARCHIV FÜR CHRISTLICH-DEMOKRATISCHE POLITIK DER KONRAD-ADENAUER-STIFTUNG E.V. 01 – 026 MARGOT KALINKE SANKT AUGUSTIN 2014 I Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Persönliches 1 2 Korrespondenz 5 3 Zonenbeirat und Wirtschaftsrat der Bizone 8 4 Deutscher Bundestag 9 4.1 Bundestagsausschuss für Sozialpolitik 9 5 Deutsche Partei (DP) 12 5.1 Parteitage der DP 14 6 CDU 16 7 Wahlen 17 7.1 Bundestagswahlen 17 7.2 Landtagswahlen Niedersachsen 18 7.3 Kommunalwahlen Niedersachsen 19 8 Materialsammlung 20 Sachbegriff-Register 21 Ortsregister 27 Personenregister 28 Biographische Angaben: 1909 04 23 geboren in Bartschin (Posen-Westpreußen), evangelisch deutsches Lyzeum und Gymnasium in Bromberg (Oberprimareife) 1925 Ausweisung aus Polen 1926 Ansiedlung in Niedersachsen höhere Handelsschule 1926-1927 kaufmännische Angestellte in der Textilindustrie 1927-1937 Leiterin einer Fabrikniederlage in Goslar und Hannover 1926-1933 Mitglied des Verbandes Weiblicher Angestellter (VWA) 1937-1946 Geschäftsführerin des Verbandes der Angestelltenkrankenkassen in Hannover 1946-1948 Mitglied des Zonenbeirats der Britischen Besatzungszone 1947-1952 Verband der Angestelltenkrankenkassen in Hamburg 1947 Mitbegründerin der Gesellschaft für Versicherungswissenschaft und -Gestaltung 1947-1949 Mitglied des Landtages in Niedersachsen (NLP) ab 1949 erneut Mitglied des Verbandes Weiblicher Angestellter (VWA), 1949-1969 Hauptausschussvorsitzende, seit 1969 Bundesvorsitzende 1949-1953 und 1955-1972 Mitglied des Bundestages, für die Wahlkreise Burgdorf-Celle und Hannover-Nord -

Speech in English (PDF, 48KB)

Translation of advance text. The speech online: www.bundespraesident.de Berlin, 24.05.2011 page 1 of 5 Federal President Christian Wulff marking the informational and contact-building visit of the Diplomatic Corps to Hambach Castle on 24 May 2011 What a pleasure it is to visit Hambach Castle together. The German people’s striving for democracy and participation has deep roots in this place. The Hambach Festival, which took place here in late May 1832, laid a very important part of the foundations for what the Ger¬man people eventually achieved with the Basic Law of the Federal Republic in 1949 and reunification in 1989/90: unity and law and freedom. Twenty to thirty thousand people came to the ruined castle here for the speeches and songs of the Hambach Festival. They were demonstrating against the Congress of Vienna decisions of 1815, which were intended to suppress national, liberal and democratic tendencies. The Festival made Germany part of the unrest that had been sweeping through Europe since 1830, from the French to the Belgians, Poles and others. In the Palatinate, the discontent among the populace gathered around Philipp Siebenpfeiffer and Johann Wirth, who campaigned through Fatherland Associations for freedom of the press. Their call to attend the Hambach Festival found resonance in all sections of the population. Women, too, were expressly included in the invitation, since it was “a mistake and a stain”, as the invitation itself has it, for women “to be disregarded politically within the European order”. They wanted the Festival to provide a powerful expression of the political objective behind it: a unified Germany of free citizens enjoying equal rights within a united Europe, surrounded by self-determined peoples. -

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Inhaltsverzeichnis Inhaltsübersicht über die Bände 2 und 3 XVIII Einleitung XXXV Abbildungsteil XL ff. 1 Wann beginnt der neue deutsch-jüdische Dialog? 3 1.1 Dr. Siegfried Moses: Die Wiedergutmachungsforderungen der Juden . 3 1.2 Bevor der offizielle Teil der Geschichte beginnt 15 1.3 Ein Gutachten von Hendrik van Dam 19 2 Die ersten Fühler werden ausgestreckt 26 2.1 Ereignisreiches Jahr 1950 26 2.2 Zum ersten Mal: Deutsche Abgeordnete bei einem Kongreß der Interparlamentarischen Union 27 2.3 Weitere Kontakte im menschlichen Bereich - Friede mit Israel 30 2.3.1 Erich Lüth und Rudolf Küstermeier 31 3 Die bedeutende Note vom 12. März 1951 — Auf dem Weg zu den deutsch-israelischen Verhandlungen 33 3.1 Die Note der israelischen Regierung zum 12. März 1951 33 3.2 Erste offizielle Überlegungen zur Wiedergutmachung in der Bundesrepublik 39 3.2.1 Kurt Schuhmachers Rede vor dem Deutschen Bundestag vom 21. September 1949 39 3.2.2 Regierungserklärung zur jüdischen Frage und zur Wieder- gutmachung 45 3.3 Auf dem Wege zu den deutsch-israelischen Verhandlungen 50 3.3.1 Deutsche Verhandlungsvorbereitungen 51 3.3.2 Die Londoner Schuldenkonferenz und die Wiedergutmachungs- verhandlungen 53 4 Die Wiedergutmachungsverhandlungen in Wassenaar 55 4.1 Der Verlauf der Verhandlungen 55 4.1.1 Das finanzielle Limit bringt Komplikationen 58 4.1.2 Prof. Böhm schreibt an den Bundeskanzler 61 4.1.3 Im Hinblick auf die Londoner Schuldenverhandlungen werden die Wassenaaer Beratungen unterbrochen 64 4.1.4 Goldmann und Böhm treffen sich in Paris 67 4.1.5 Das Kommunique -

Security Versus Unity: Germany's Dilemma II

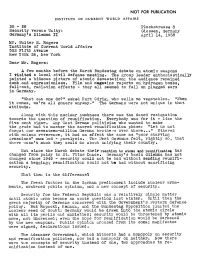

NOT FOR PUBLICATION INSTITUTE OF CURRENT VORLD AFFAIRS DB- 8 Plockstrasse 8 Security versus Unity: Gie ssen, Germany Germany' s Dilemma II April l, 19G8 Mr. Walter S. Rogers Institute of Current World Affairs 522 Fifth Avenue ew York 36, Eew York Dear Mr. Rogers: A few months before the -arch Bundestag debate on atomic weapons I Islted a local civil defense meeting. The group leader enthusiastically painted a hideous picture of atomic devastation; the audience remained dumb arid expressionless. Film and magazine reports on hydrogen bombs, fall-out, radiation effects they all seeme to fall on plugged ears in Germany. "at can one do?"'asked Kurt Odrig, who sells me vegetables. "Yhen it comes, we're all goers anyway." The Germans were not uique in that attitude. Along with this nuclear numbness there was the dazed resignation towards the question of reunification. Everybody was for it like the fiv cent clgar. Any West German politlclan who wanted to make the rade had to master the sacred roeunification phase: "Let us not forget our seventeen-million German brothe.,,_s over there..." Uttered ith solen reverence, it had an effect tho same as ,'poor starving rmenlans" ,once had paralysis. The Test Germans felt, rightly so, that there ,sn't much they could do about uifying their country. But since the arch debate their ,reaction to atoms and reunificatoa has changed from palsy to St. Vitus Dance. Germany's basic dilemma has not changed since 1949 security could not be had without sending reunifi- cation a begging; reunification could not be had without sacrificing security. -

German-American Elite Networking, the Atlantik-Brücke and the American Council on Germany, 1952-1974

Northumbria Research Link Citation: Zetsche, Anne (2016) The Quest for Atlanticism: German-American Elite Networking, the Atlantik-Brücke and the American Council on Germany, 1952-1974. Doctoral thesis, Northumbria University. This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/31606/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html The Quest for Atlanticism: German-American Elite Networking, the Atlantik-Brücke and the American Council on Germany, 1952-1974 Anne Zetsche PhD 2016 The Quest for Atlanticism: German-American Elite Networking, the Atlantik-Brücke and the American Council on Germany, 1952-1974 Anne Zetsche, MA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Northumbria at Newcastle for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Research undertaken in the Department of Humanities August 2016 Abstract This work examines the role of private elites in addition to public actors in West German- American relations in the post-World War II era and thus joins the ranks of the “new diplomatic history” field.