Paramilitary Organizations in Germany from 1871–1945

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Fascism Revisited

Stefan Vogt. Nationaler Sozialismus und Soziale Demokratie: Die sozialdemokratische Junge Rechte 1918-1945. Bonn: Verlag J.H.W. Dietz Nachf., 2006. 502 S. gebunden, ISBN 978-3-8012-4161-2. Reviewed by Eric Kurlander Published on H-German (May, 2007) During the tumultuous fourteen years of the ed the chief bulwark against both communism Weimar Republic, members of the Communist and fascism. Indeed, leading socialist moderates, Party (KPD) regularly assailed their moderate So‐ sometimes referred to as the Junge Rechte, en‐ cial Democratic Party (SPD) colleagues with accu‐ dorsed "social market" capitalism, peaceful revi‐ sations of "social fascism." By allying with bour‐ sion of the Versailles Treaty, and a bourgeois al‐ geois parties in defense of a liberal democratic liance in defense of liberal democracy. Though state, the Communists argued, the SPD fomented they failed in staving off fascism, these historians nationalist revisionism, monopoly capitalism, argue," the "young Right" succeeded in paving the and--inevitably--fascism. Few western scholars way for the social liberalism of postwar ("Bad have accepted this critique in its entirety, but Godesberg") Social Democracy.[2] many have blamed the Majority Socialists' initial Stefan Vogt's new intellectual history rejects vacillation between Left and Right for the weak‐ this bourgeois revisionism out of hand, adding a ness and ultimate collapse of the Weimar Repub‐ new wrinkle to the "social fascist" paradigm of the lic. Rather than nationalizing heavy industry, 1930s. In Vogt's provocative reading of events, purging the monarchist bureaucracy, or breaking Weimar social democracy enabled fascism not up Junker estates, the SPD colluded with right- only in its hostility to the communist Left but in wing paramilitary groups in 1919 to suppress its ideological commitment to the radical Right. -

Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg-Kaliningrad, 1928-1948

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg-Kaliningrad, 1928-1948 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6r33q03k Author Eaton, Nicole M. Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg–Kaliningrad, 1928-1948 By Nicole M. Eaton A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Yuri Slezkine, chair Professor John Connelly Professor Victoria Bonnell Fall 2013 Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg–Kaliningrad, 1928-1948 © 2013 By Nicole M. Eaton 1 Abstract Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg-Kaliningrad, 1928-1948 by Nicole M. Eaton Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Yuri Slezkine, Chair “Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg-Kaliningrad, 1928-1948,” looks at the history of one city in both Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Russia, follow- ing the transformation of Königsberg from an East Prussian city into a Nazi German city, its destruction in the war, and its postwar rebirth as the Soviet Russian city of Kaliningrad. The city is peculiar in the history of Europe as a double exclave, first separated from Germany by the Polish Corridor, later separated from the mainland of Soviet Russia. The dissertation analyzes the ways in which each regime tried to transform the city and its inhabitants, fo- cusing on Nazi and Soviet attempts to reconfigure urban space (the physical and symbolic landscape of the city, its public areas, markets, streets, and buildings); refashion the body (through work, leisure, nutrition, and healthcare); and reconstitute the mind (through vari- ous forms of education and propaganda). -

Der Hitler-Prozess Deutschland 1924

Der Hitler-Prozess Deutschland 1924 von Prof. Dr. Peter Reichel 1. Die Staatskrise Schon das fünfte Jahr hätte ihr Ende sein können. Die Weimarer Republik wankte, sie war im Herbst 1923 dem Abgrund nah. Ein autoritärer Umbau des Staates gelang der nationalen Rechten allerdings noch nicht. Der Reichspräsident verhinderte dies, indem er darauf einging. Zwar stärkte Ebert in der Staatskrise die Machtstellung seines leitenden Generals von Seeckt. Doch dieser putschte nicht. Er stand als Legalist zu seinem Amtseid auf die Verfassung der parlamentarischen Demokratie, die er politisch ablehnte. Das hatte er schon bei der Abwehr des Kapp-Putsches im Frühjahr 1920 getan und im Kampf gegen die linksradikalen Feinde der Republik im Winter 1918/19. Der Präsident vertraute seinem General, er hatte keine Wahl. Im Januar 1923 besetzten Belgier und Franzosen das Ruhrgebiet, um Deutschland zur Erfüllung seiner Reparationsverpflichtungen zu zwingen. Die Regierung des parteilosen Reichskanzlers und Hamburger Hapag-Direktors Wilhelm Cuno stellte daraufhin nicht nur die Zahlungen und Sachlieferungen an die Siegermächte ein. Sie forderte die Bevölkerung darüber hinaus auch zum „passiven Widerstand“ auf. Der Konflikt eskalierte. Die Besatzungsmächte verschärften ihre Repression und zugleich ihre Kooperation mit den wiederauflebenden separatistischen Bestrebungen, gegen die wiederum die nationalistischen Freikorps Front machten. Sie hatten zuvor im Baltikum, in Bayern und in Oberschlesien gekämpft. Das Reich geriet in eine Zwickmühle. Die deutschen Behörden waren auf dem besetzten Territorium machtlos. Zugleich mussten die immensen Kosten für die „Zwangsarbeitslosen“ und die Kohlekäufe durch die Notenpresse gedeckt werden. Der Geldwertverlust nahm dadurch rapide zu. Und mit ihm das soziale Elend und die politischen Unruhen. Gewinner waren die Protestparteien an der Peripherie Deutschlands und an den Rändern des politischen Spektrums. -

Speer: an Artist Or a Monster?

Constructing the Past Volume 7 Issue 1 Article 14 2006 Speer: An Artist or a Monster? Emily K. Ergang Illinois Wesleyan University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/constructing Recommended Citation Ergang, Emily K. (2006) "Speer: An Artist or a Monster?," Constructing the Past: Vol. 7 : Iss. 1 , Article 14. Available at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/constructing/vol7/iss1/14 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by editorial board of the Undergraduate Economic Review and the Economics Department at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Speer: An Artist or a Monster? Abstract This article discusses the life of Albert Speer, who was hired as an architect by Hitler. It describes him as being someone who worked for a career and ignored the political implications of who he was working for. This article is available in Constructing the Past: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/constructing/vol7/iss1/14 Constructing the Past Speer: An Artist or a Monster? Emily Kay Ergang The regime of Adolf Hitler and his Nazi party produced a number of complex and controversial. -

Geschichte Des Nationalsozialismus

Ernst Piper Ernst Ernst Piper Geschichte des Nationalsozialismus Von den Anfängen bis heute Geschichte des Nationalsozialismus Band 10264 Ernst Piper Geschichte des Nationalsozialismus Schriftenreihe Band 10291 Ernst Piper Geschichte des Nationalsozialismus Von den Anfängen bis heute Ernst Piper, 1952 in München geboren, lebt heute in Berlin. Er ist apl. Professor für Neuere Geschichte an der Universität Potsdam, Herausgeber mehrerer wissenschaft- licher Reihen und Autor zahlreicher Bücher zur Geschichte des 19. und 20. Jahrhun- derts. Zuletzt erschienen Nacht über Europa. Kulturgeschichte des Ersten Weltkriegs (2014), 1945 – Niederlage und Neubeginn (2015) und Rosa Luxemburg. Ein Leben (2018). Diese Veröffentlichung stellt keine Meinungsäußerung der Bundeszentrale fürpolitische Bildung dar. Für die inhaltlichen Aussagen trägt der Autor die Verantwortung. Wir danken allen Lizenzgebenden für die freundlich erteilte Abdruckgenehmigung. Die In- halte der im Text und im Anhang zitierten Internetlinks unterliegen der Verantwor- tung der jeweiligen Anbietenden; für eventuelle Schäden und Forderungen überneh- men die Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung / bpb sowie der Autor keine Haftung. Bonn 2018 © Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung Adenauerallee 86, 53113 Bonn Projektleitung: Hildegard Bremer, bpb Lektorat: Verena Artz Umschlagfoto: © ullstein bild – Fritz Eschen, Januar 1945: Hausfassade in Berlin-Wilmersdorf Umschlaggestaltung, Satzherstellung und Layout: Naumilkat – Agentur für Kommunikation und Design, Düsseldorf Druck: Druck und Verlagshaus Zarbock GmbH & Co. KG, Frankfurt / Main ISBN: 978-3-7425-0291-9 www.bpb.de Inhalt Einleitung 7 I Anfänge 18 II Kampf 72 III »Volksgemeinschaft« 136 IV Krieg 242 V Schuld 354 VI Erinnerung 422 Anmerkungen 450 Zeittafel 462 Abkürzungen 489 Empfehlungen zur weiteren Lektüre 491 Bildnachweis 495 5 Einleitung Dieses Buch ist eine Geschichte des Nationalsozialismus, keine deutsche Geschichte des 20. -

Classics of the Military Field in the Social Sciences

Classics of the Military Field in the Social Sciences Karl Demeter, Das deutsche Offizierkorps in seinen historisch-soziologischen Grundlagen, Berlin, Verlag von Reimar Hobbing, 1930 ; Das deutsche Heer und seine Offiziere, Berlin, Verlag von Reimar Hobbing, 1935 ; Das deutsche Offizierkorps in Gesellschaft und Staat, 1650-1945, Frankfurt am Main, Bernard & Graefe Verlag für Wehrwesen, 1962. English translation, with an introduction by Michael Howard : The German Officer Corps in Society and State, 1650-1945, New York, Praeger, 1965. Presented by Bengt Abrahamsson The books by Karl Demeter listed above obviously have the same theme, and share much the same substance. Indeed, the question can be asked whether they are the same book under various titles, revised and augmented as time went by over more than thirty years, or whether they can be regarded as distinct contributions. The main difference, of course, is that the later editions cover the Third Reich period. While little is known about their reception in Europe apart from Germany (where Demeter seems to have enjoyed high esteem to this day), they powerfully influenced American historiography and military sociology at different times, and with different impacts. This writer’s contention is that despite such differences, they ought to be presented together. The main reference in what follows naturally is to the 1962 version. oOo On 25th May 1934, Gen. von Blomberg, then Minister of Defence in Adolf Hitler’s government, issued the following order to the officers of the German armed forces : “The old practice of seeking company within a particular social class is no longer any part of the duty of the corps of officers. -

Preprint Heft 9

PREPRINT 9 Elisabeth Kraus Repräsentation – Renommee – Rekrutierung Mäzenatentum für das Deutsche Museum Preprint 9 Elisabeth Kraus Repräsentation - Renommee – Rekrutierung Mäzenatentum für das Deutsche Museum 2013 Inhalt Abstract 5 1. Einleitung 7 1.1 Bedeutung des Themas und seiner Erforschung 7 1.2 Begrifflichkeit 8 1.3 Fragestellungen 12 1.4 Stand der Forschung und Quellenlage 14 1.5 Auswahlgesichtspunkte und Vorgehen 20 2. Die Gründungsphase (1903–1923) 23 2.1 Das fürstlich-aristokratische Mäzenatentum 23 2.2 Zuwendungen von Deutschem Reich, Königreich Bayern, München und anderen Städten 26 2.3 Das bürgerliche Mäzenatentum 28 2.3.1 Industrie, Verbände, Vereinigungen 28 2.3.2 Privatpersonen 33 2.4 Die Reisestipendienstiftung von 1911 43 2.5 Netzwerke, Spendenakquisition, Gegengaben – eine erste Bilanz des Mäzenatentums 52 3. Die Auf- und Ausbauphase (1923/25–1933) 56 3.1 Zuwendungen nach der Hyperinflation – die 1000-Mark-Spende 56 3.2 Die Reisestipendienstiftung 58 3.3 Die Oskar-von-Miller-Stiftung der Reichsregierung (1925) 60 3.4 Die Krupp-Stiftung für Büchergaben (1928) 66 3.5 Die Frauenspende für die Bibliothek des Deutschen Museums (1928) 68 3.6 Die Adolf und Luisa Haeuser-Stiftung für Museumsangestellte (1930) 73 3.7 Die St. Ansgar-Stiftung (1933) 77 3.8 Stiftungen, Spenden, Ehrungen – die »Goldenen Zwanziger Jahre« des Mäzenatentums? 81 4. Die NS- und Kriegszeit (1933–1945) 89 4.1 Die Finanzierung zwischen Gründungsauftrag und Anpassungserfordernis 93 4.2 Die »Entjudung« des Museumsausschusses 102 4.3 Die »Entjudung«, »Nazifizierung« und Entwicklung der (Zu-) Stiftungen 107 4.4 Das Mäzenatentum in »brauner« Zeit 118 3 5. Revitalisierung und Konsolidierung (1945/48–1958/60) 122 5.1 Neustart 122 5.2 Spendenwesen und Fundraising-Strategien 124 5.3 Entwicklung und Zusammenlegung der Zustiftungen 130 5.4 Mäzenatentum in Bronze? 133 6. -

Martin Bormann

Martin Bormann Hitlers Vollstrecker von Volker Koop 1. Auflage Martin Bormann – Koop schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei beck-shop.de DIE FACHBUCHHANDLUNG Thematische Gliederung: Biographien & Autobiographien: Historisch, Politisch, Militärisch Böhlau Köln/Wien 2012 Verlag C.H. Beck im Internet: www.beck.de ISBN 978 3 412 20942 1 Inhaltsverzeichnis: Martin Bormann – Koop Hitlers Vollstrecker Volker Koop ist Zeithistoriker und Bormann Martin Journalist und lebt in Berlin. Skelett gefunden. Er wurde offiziell für tot Martin Bormann, Leiter der Partei-Kanzlei der NSDAP und »Sekretär Martin Bormann (1900–1945) war einer erklärt. Inzwischen wurde nachgewiesen, des Führers«, war einer der mächtigsten und am meisten gefürchteten der am meisten gehassten NS-Funktionäre. dass Bormann am 2. Mai 1945 zur Giftkap- Männer im Dritten Reich. Als zwanghafter Bürokrat steuerte er Hitlers Als Leiter der Partei-Kanzlei der NSDAP im sel gegriffen hatte. Apparat des Terrors und der Verbrechen derart effektiv, dass er zum Rang eines Reichsministers und Privatse- Zahlreiche, erst seit Kurzem zugänglich ge- heimlichen Herrscher Deutschlands wurde. Volker Koop zeigt, in welch kretär Hitlers wurde er von Ministern, Gau- wordene Dokumente ermöglichen es jetzt, hohem Ausmaß er die zerstörerische Dynamik des NS-Regimes prägte. leitern, Beamten, Richtern und Generälen die Biographie von Hitlers treuestem Vasal- gefürchtet. Bormann identifizierte sich mit Volker Koop Volker len neu zu schreiben. Volker Koop führt dem Martin Hitlers Vorstellungen von Rassenpolitik, Ju- Leser die Machtfülle und Skrupellosigkeit denvernichtung und Zwangsarbeit und des im Schatten des »Führers« operieren- machte sich als sein Vollstrecker für die De- den zweitmächtigsten Mannes im Dritten Bormann tail- und Schmutzarbeit unentbehrlich. Eis- Reich vor Augen. -

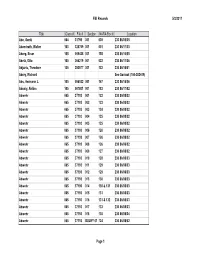

5/3/2011 FBI Records Page 1 Title Class # File # Section NARA Box

FBI Records 5/3/2011 Title Class # File # Section NARA Box # Location Abe, Genki 064 31798 001 039 230 86/05/05 Abendroth, Walter 100 325769 001 001 230 86/11/03 Aberg, Einar 105 009428 001 155 230 86/16/05 Abetz, Otto 100 004219 001 022 230 86/11/06 Abjanic, Theodore 105 253577 001 132 230 86/16/01 Abrey, Richard See Sovloot (100-382419) Abs, Hermann J. 105 056532 001 167 230 86/16/06 Abualy, Aldina 105 007801 001 183 230 86/17/02 Abwehr 065 37193 001 122 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 002 123 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 003 124 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 004 125 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 005 125 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 006 126 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 007 126 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 008 126 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 009 127 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 010 128 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 011 129 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 012 129 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 013 130 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 014 130 & 131 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 015 131 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 016 131 & 132 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 017 133 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 018 135 230 86/08/04 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 01 124 230 86/08/02 Page 1 FBI Records 5/3/2011 Title Class # File # Section NARA Box # Location Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 20 127 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 33 132 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 33 132 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 33 133 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 35 134 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 EBF 014X 123 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 EBF 014X 123 230 86/08/02 Abwehr -

Modern History

MODERN HISTORY The Role of Youth Organisations in Nazi Germany: 1933-1939 It is often believed that children and adolescents are the most impressionable and vulnerable in society. Unlike adults, who have already developed their own established social views and political opinions, juveniles are still in the process of forming their attitudes and judgements on the world around them, so can easily be manipulated into following certain ideas and principles. This has been a fact widely taken advantage of by governments and political parties throughout history, in particular, by the Nazi Party under Adolf Hitler’s leadership between 1933 and 1939. The beginning of the 1930’s ushered in a new period of instability and uncertainty throughout Germany and with the slow but eventual collapse of the Weimar Government, as well as the start of the Great Depression, the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP) took the opportunity to gain a large and devoted following. This committed and loyal support was gained by appealing primarily to the industrial working class and the rural and farming communities, under the tenacious direction of nationalist politician Adolf Hitler. Through the use of powerful and persuasive propaganda, the Nazis presented themselves as ‘the party above class interests’1, a representation of hope, prosperity and unyielding leadership for the masses of struggling Germans. The appointment of NSDAP leader, Adolf Hitler, as chancellor of Germany on January 30th 1933, further cemented his reputation as the strong figure of guidance Germany needed to progress and prosper. On March 23rd 1933, the ‘Enabling Act’ was passed by a two thirds majority in the Reichstag, resulting in the suspension of the German Constitution and the rise of Hitler’s dictatorship. -

German History Reflected

The Detlev Rohwedder Building German history reflected GFE = 1/2 Formathöhe The Detlev Rohwedder Building German history reflected Contents 3 Introduction 44 Reunification and Change 46 The euphoria of unity 4 The Reich Aviation Ministry 48 A tainted place 50 The Treuhandanstalt 6 Inception 53 The architecture of reunification 10 The nerve centre of power 56 In conversation with 14 Courage to resist: the Rote Kapelle Hans-Michael Meyer-Sebastian 18 Architecture under the Nazis 58 The Federal Ministry of Finance 22 The House of Ministries 60 A living place today 24 The changing face of a colossus 64 Experiencing and creating history 28 The government clashes with the people 66 How do you feel about working in this building? 32 Socialist aspirations meet social reality 69 A stroll along Wilhelmstrasse 34 Isolation and separation 36 Escape from the state 38 New paths and a dead-end 72 Chronicle of the Detlev Rohwedder Building 40 Architecture after the war – 77 Further reading a building is transformed 79 Imprint 42 In conversation with Jürgen Dröse 2 Contents Introduction The Detlev Rohwedder Building, home to Germany’s the House of Ministries, foreshadowing the country- Federal Ministry of Finance since 1999, bears wide uprising on 17 June. Eight years later, the Berlin witness to the upheavals of recent German history Wall began to cast its shadow just a few steps away. like almost no other structure. After reunification, the Treuhandanstalt, the body Constructed as the Reich Aviation Ministry, the charged with the GDR’s financial liquidation, moved vast site was the nerve centre of power under into the building. -

Spion Bei Der NATO

Bamler_innen 04.02.2014 12:47 Uhr Seite 3 Peter Böhm Spion bei der NATO Hans-Joachim Bamler, der erste Resident der HV A in Paris Sämtliche Inhalte, Fotos, Texte und Graphiken dieser Leseprobe sind urheberrechtlich geschützt. Sie dürfen ohne !orherige schriftliche Genehmigung "eder ganz noch auszugs"eise kopiert, !erändert, !er!ielfältigt oder !er#$entlicht "erden. Impressum ISBN 978-3-360-01856-4 © 2014 edition ost im Verlag Das Neue Berlin, Berlin Umschlaggestaltung: Buchgut, Berlin, unter Verwendung eines Fotos von Hans-Joachim Bamler, 1966 Fotos: Archiv Bamler S. 14, 16, 19, 39, 41, 44, 49, 57, 63, 75, 81, 87, 91, 130, 145, 147, 160, 171, 186, 193, 195, 203; Peter Böhm S. 35, 102, 112, 135, 140, 143, 144, 150, 153, 159, 164, 175, 179, 184, 188; Robert Allertz 1, 165, 189 Die Bücher der edition ost und des Verlags Das Neue Berlin erscheinen in der Eulenspiegel Verlagsgruppe. www.edition-ost.de Bamler_innen 04.02.2014 12:47 Uhr Seite 1 Das Buch Der Autor Hans-Joachim Bamler und Peter Böhm, Jahrgang 1950, seine Frau Marianne wur- nach dem Philosophiestu- den zu Beginn der 60er dium Hochschullehrer, Jahre nach Paris geschickt, anschließend im Internatio- als sich dort das Hauptquar- nalen Pressezentrum der tier der NATO befand. Dort DDR (IPZ) in Berlin tätig. besaß die Auslandsaufklä- Nach 1990 Pressereferent rung der DDR eine »Quelle«. und freier Journalist. Zu deren Betreuung wurde eine Residentur gebraucht: Bamlers Auftrag lautete, diese aufzubauen und zu führen. Die französische Spionageabwehr entdeckte sie. Jochen Bamler wurde zu 18, Marianne zu 12 Jahren Haft verurteilt, von denen sie mehr als sieben und er über acht Jahre in verschiedenen Haftanstalten unter widrig- sten Verhältnissen absaßen.