AUTOBIOGRAPHY of SIR GEORGE BIDDELL AIRY, K.C.B., By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes on the Parish of Mylor, Cornwall

C.i i ^v /- NOTES ON THE PARISH OF MYLOR /v\. (crt MVI.OK CII r RCII. -SO UIH I'OKCil AND CROSS O !• ST. MlLoKIS. [NOTES ON THE PARISH OF MYLOR CORNWALL. BY HUGH P. OLIVEY M.R.C.S. Uaunton BARNICOTT &- PEARCE, ATHEN^UM PRESS 1907 BARNICOTT AND PEARCE PRINTERS Preface. T is usual to write something as a preface, and this generally appears to be to make some excuse for having written at all. In a pre- face to Tom Toole and his Friends — a very interesting book published a few years ago, by Mrs. Henry Sandford, in which the poets Coleridge and Wordsworth, together with the Wedgwoods and many other eminent men of that day figure,—the author says, on one occasion, when surrounded by old letters, note books, etc., an old and faithful servant remon- " " strated with her thus : And what for ? she " demanded very emphatically. There's many a hundred dozen books already as nobody ever reads." Her hook certainly justified her efforts, and needed no excuse. But what shall I say of this } What for do 1 launch this little book, which only refers to the parish ot Mylor ^ vi Preface. The great majority of us are convinced that the county of our birth is the best part of Eng- land, and if we are folk country-born, that our parish is the most favoured spot in it. With something of this idea prompting me, I have en- deavoured to look up all available information and documents, and elaborate such by personal recollections and by reference to authorities. -

The Female Art of War: to What Extent Did the Female Artists of the First World War Con- Tribute to a Change in the Position of Women in Society

University of Bristol Department of History of Art Best undergraduate dissertations of 2015 Grace Devlin The Female Art of War: To what extent did the female artists of the First World War con- tribute to a change in the position of women in society The Department of History of Art at the University of Bristol is commit- ted to the advancement of historical knowledge and understanding, and to research of the highest order. We believe that our undergraduates are part of that endeavour. For several years, the Department has published the best of the annual dis- sertations produced by the final year undergraduates in recognition of the excellent research work being undertaken by our students. This was one of the best of this year’s final year undergraduate disserta- tions. Please note: this dissertation is published in the state it was submitted for examination. Thus the author has not been able to correct errors and/or departures from departmental guidelines for the presentation of dissertations (e.g. in the formatting of its footnotes and bibliography). © The author, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means without the prior permission in writing of the author, or as expressly permitted by law. All citations of this work must be properly acknowledged. Candidate Number 53468 THE FEMALE ART OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR 1914-1918 To what extent did the female artists of the First World War contribute to a change in the position of women in society? Dissertation submitted for the Degree of B.A. -

Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 1

Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 1 CHAPTER I. CHAPTER II. CHAPTER III. CHAPTER IV. CHAPTER V. CHAPTER VI. CHAPTER VII. CHAPTER VIII. CHAPTER IX. CHAPTER X. CHAPTER I. CHAPTER II. CHAPTER III. CHAPTER IV. CHAPTER V. CHAPTER VI. CHAPTER VII. CHAPTER VIII. CHAPTER IX. CHAPTER X. Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy The Project Gutenberg EBook of Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 2 License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy Author: George Biddell Airy Release Date: January 9, 2004 [EBook #10655] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SIR GEORGE AIRY *** Produced by Joseph Myers and PG Distributed Proofreaders AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF SIR GEORGE BIDDELL AIRY, K.C.B., M.A., LL.D., D.C.L., F.R.S., F.R.A.S., HONORARY FELLOW OF TRINITY COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE, ASTRONOMER ROYAL FROM 1836 TO 1881. EDITED BY WILFRID AIRY, B.A., M.Inst.C.E. 1896 PREFACE. The life of Airy was essentially that of a hard-working, business man, and differed from that of other hard-working people only in the quality and variety of his work. It was not an exciting life, but it was full of interest, and his work brought him into close relations with many scientific men, and with many men high in the State. -

Review of Wren's 'Tracts' on Architecture and Other Writings, by Lydia M

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College History of Art Faculty Research and Scholarship History of Art 2000 Review of Wren's 'Tracts' on Architecture and Other Writings, by Lydia M. Soo David Cast Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Custom Citation Cast, David. Review of Wren's 'Tracts' on Architecture and Other Writings, by Lydia M. Soo. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 59 (2000): 251-252, doi: 10.2307/991600. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs/1 For more information, please contact [email protected]. produced new monograph? In this lished first in 1881, have long been used fouryears later under the titleLives of the respect, as in so many others, one fin- by historians: byJohn Summerson in his Professorsof GreshamCollege), which evi- ishes reading Boucher by taking one's still seminal essay of 1936, and by Mar- dently rekindledChristopher's interest hat off to Palladio.That in itself is a garet Whinney, Eduard Sekler, Kerry in the project.For the next few yearshe greattribute to this book. Downes, and most notably and most addedmore notations to the manuscript. -PIERRE DE LA RUFFINIERE DU PREY recently by J. A. Bennett. And the his- In his own volume,John Wardreferred Queen'sUniversity at Kingston,Ontario tory of their writing and printings can be to this intendedpublication as a volume traced in Eileen Harris's distinguished of plates of Wren'sworks, which "will study of English architectural books. -

Wren and the English Baroque

What is English Baroque? • An architectural style promoted by Christopher Wren (1632-1723) that developed between the Great Fire (1666) and the Treaty of Utrecht (1713). It is associated with the new freedom of the Restoration following the Cromwell’s puritan restrictions and the Great Fire of London provided a blank canvas for architects. In France the repeal of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 revived religious conflict and caused many French Huguenot craftsmen to move to England. • In total Wren built 52 churches in London of which his most famous is St Paul’s Cathedral (1675-1711). Wren met Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680) in Paris in August 1665 and Wren’s later designs tempered the exuberant articulation of Bernini’s and Francesco Borromini’s (1599-1667) architecture in Italy with the sober, strict classical architecture of Inigo Jones. • The first truly Baroque English country house was Chatsworth, started in 1687 and designed by William Talman. • The culmination of English Baroque came with Sir John Vanbrugh (1664-1726) and Nicholas Hawksmoor (1661-1736), Castle Howard (1699, flamboyant assemble of restless masses), Blenheim Palace (1705, vast belvederes of massed stone with curious finials), and Appuldurcombe House, Isle of Wight (now in ruins). Vanburgh’s final work was Seaton Delaval Hall (1718, unique in its structural audacity). Vanburgh was a Restoration playwright and the English Baroque is a theatrical creation. In the early 18th century the English Baroque went out of fashion. It was associated with Toryism, the Continent and Popery by the dominant Protestant Whig aristocracy. The Whig Thomas Watson-Wentworth, 1st Marquess of Rockingham, built a Baroque house in the 1720s but criticism resulted in the huge new Palladian building, Wentworth Woodhouse, we see today. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Summerfield, Angela (2007). Interventions : Twentieth-century art collection schemes and their impact on local authority art gallery and museum collections of twentieth- century British art in Britain. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University, London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17420/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] 'INTERVENTIONS: TWENTIETH-CENTURY ART COLLECTION SCIIEMES AND TIIEIR IMPACT ON LOCAL AUTHORITY ART GALLERY AND MUSEUM COLLECTIONS OF TWENTIETII-CENTURY BRITISH ART IN BRITAIN VOLUME If Angela Summerfield Ph.D. Thesis in Museum and Gallery Management Department of Cultural Policy and Management, City University, London, August 2007 Copyright: Angela Summerfield, 2007 CONTENTS VOLUME I ABSTRA.CT.................................................................................. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS •........••.••....••........•.•.•....•••.......•....•...• xi CHAPTER 1:INTRODUCTION................................................. 1 SECTION 1 THE NATURE AND PURPOSE OF PUBLIC ART GALLERIES, MUSEUMS AND THEIR ART COLLECTIONS.......................................................................... -

Books Added to Benner Library from Estate of Dr. William Foote

Books added to Benner Library from estate of Dr. William Foote # CALL NUMBER TITLE Scribes and scholars : a guide to the transmission of Greek and Latin literature / by L.D. Reynolds and N.G. 1 001.2 R335s, 1991 Wilson. 2 001.2 Se15e Emerson on the scholar / Merton M. Sealts, Jr. 3 001.3 R921f Future without a past : the humanities in a technological society / John Paul Russo. 4 001.30711 G163a Academic instincts / Marjorie Garber. Book of the book : some works & projections about the book & writing / edited by Jerome Rothenberg and 5 002 B644r Steven Clay. 6 002 OL5s Smithsonian book of books / Michael Olmert. 7 002 T361g Great books and book collectors / Alan G. Thomas. 8 002.075 B29g Gentle madness : bibliophiles, bibliomanes, and the eternal passion for books / Nicholas A. Basbanes. 9 002.09 B29p Patience & fortitude : a roving chronicle of book people, book places, and book culture / Nicholas A. Basbanes. Books of the brave : being an account of books and of men in the Spanish Conquest and settlement of the 10 002.098 L552b sixteenth-century New World / Irving A. Leonard ; with a new introduction by Rolena Adorno. 11 020.973 R824f Foundations of library and information science / Richard E. Rubin. 12 021.009 J631h, 1976 History of libraries in the Western World / by Elmer D. Johnson and Michael H. Harris. 13 025.2832 B175d Double fold : libraries and the assault on paper / Nicholson Baker. London booksellers and American customers : transatlantic literary community and the Charleston Library 14 027.2 R196L Society, 1748-1811 / James Raven. -

Modern British, Irish and East Anglian Art Tuesday 19 November 2013 at 1Pm Knightsbridge, London

Modern British, Irish and East Anglian Art Tuesday 19 November 2013 at 1pm Knightsbridge, London Modern British, Irish and East Anglian Art Tuesday 19 November 2013 at 1pm Knightsbridge Bonhams Bids Enquiries Please see page 2 for bidder Montpelier Street +44 (0) 20 7447 7448 Modern British & Irish Art information including after-sale Knightsbridge +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax Emma Corke collection and shipment London SW7 1HH To bid via the internet please visit +44 (0) 20 7393 3949 www.bonhams.com www.bonhams.com [email protected] Please see back of catalogue for important notice to bidders Viewings Please note that bids should be Shayn Speed submitted no later than 24 hours +44 (0) 20 7393 3909 Illustration [email protected] East Anglian Pictures only before the sale. Front cover: Lot 91 The Guildhall Back cover: Lot 216 East Anglian Pictures Guildhall Street New bidders must also provide Inside front: Lot 46 Daniel Wright Bury St Edmunds proof of identity when submitting Inside back: Lot 215 +44 (0) 1284 716195 Suffolk, IP33 1PS bids. Failure to do this may result [email protected] in your bids not being processed. Tuesday 5 November 9am to 7pm Bidding by telephone will only be Customer Services Monday to Friday 8.30am to 6pm Wednesday 6 November accepted on a lot with a lower +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 9am to 4pm estimate in excess of £400. ----------- St Michael’s Hall Sale Number: 20779 Church Street Live online bidding is Reepham available for this sale Catalogue: £12 Norfolk, NR10 4JW Please email [email protected] with “Live bidding” in the subject Tuesday 12 November line 48 hours before the auction 9am to 7pm to register for this service. -

January 2012 Contents

International Association of Mathematical Physics News Bulletin January 2012 Contents International Association of Mathematical Physics News Bulletin, January 2012 Contents Tasks ahead 3 A centennial of Rutherford’s Atom 4 Open problems about many-body Dirac operators 11 Mathematical analysis of complex networks and databases 17 ICMP12 News 23 NSF support for ICMP participants 26 News from the IAMP Executive Committee 27 Bulletin editor Valentin A. Zagrebnov Editorial board Evans Harrell, Masao Hirokawa, David Krejˇciˇr´ık, Jan Philip Solovej Contacts http://www.iamp.org and e-mail: [email protected] Cover photo: The Rutherford-Bohr model of the atom made an analogy between the Atom and the Solar System. (The artistic picture is “Solar system” by Antar Dayal.) The views expressed in this IAMP News Bulletin are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IAMP Executive Committee, Editor or Editorial board. Any complete or partial performance or reproduction made without the consent of the author or of his successors in title or assigns shall be unlawful. All reproduction rights are henceforth reserved, mention of the IAMP News Bulletin is obligatory in the reference. (Art.L.122-4 of the Code of Intellectual Property). 2 IAMP News Bulletin, January 2012 Editorial Tasks ahead by Antti Kupiainen (IAMP President) The elections for the Executive Committee of the IAMP for the coming three years were held last fall and the new EC started its work beginning of this year. I would like to thank on behalf of all of us in the EC the members of IAMP for choosing us to steer our Association during the coming three years. -

The Man from Penzance – Sir Humphry Davy (1778–1829)

MATERIALS WORLD The man from Penzance – Sir Humphry Davy (1778 –1829) Davy saw science to be the ultimate truth. He loved the utility and permanence of it and the feeling of progression. He was a bold chemist and an inventor, but he thought like a writer. Ledetta Asfa-Wossen takes a look at his life. 2 1815 92 The number of weeks The year Davy The number of lives Davy took to devise presented his paper claimed at Felling the mining safety on the mining Colliery, Gateshead, lamp at the Royal safety lamp Tyne and Wear, Institution in 1812 avy was out to beat the clock. It was as though he knew he would stop dead at 50. As a young boy, he needed no encouragement. Inquisitive and resourceful, he leapt about with fishing tackle in one pocket and mineral specimens in the other. The eldest of five children and with Dhis father dying at 16, he grew up fast. He taught himself theology, philosophy, poetics, several sciences and seven languages, including Hebrew and Italian. Within a year, he had become a surgeon’s and apothecary’s apprentice. A few years later, he came into contact with a man called Davies Giddy (later known as Davies Gilbert). Gilbert was intrigued by Davy’s behaviour and approach to scientific study. Davy had read Lavoisier’s Traité Élémentaire de Chemie and wanted to repeat his experiments. Gilbert loaned him the use of his library and supported his experimental work. These years were the making of Davy. He cemented himself as a scientist and independent thinker on scientific issues of the time, such as the nature of heat, light and electricity, and began to criticise the doctrines of this chemistry heavyweight. -

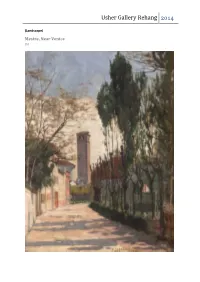

Usher Gallery Rehang 2014

Usher Gallery Rehang 2014 (Landscape) Mestre, Near Venice Oil Usher Gallery Rehang 2014 (Landscape) Church of St. Maria Della Salute, c.1885 Oil Usher Gallery Rehang 2014 (Landscape) Venice Oil (Landscape) Venice Oil Usher Gallery Rehang 2014 (Still Life) Flowers in a Persian Bottle Oil Usher Gallery Rehang 2014 (Still Life) Daffodils Oil Usher Gallery Rehang 2014 (Still Life) Garden Flowers Oil Usher Gallery Rehang 2014 Michiel Jansz. van Miereveldt – (1 May 1567 – 27 June 1641) About The artist, Michiel Jansz. van Miereveldt was born in the Delft and was one of the most successful Dutch portraitists of the 17th century. His works are predominantly head and shoulder portraits, often against a monochrome background. The viewer is drawn towards the sitter’s face by light accents revealed by clothing. After his initial training, Mierevelt quickly turned to portraiture. He gained success in this medium, becoming official painter of the court and gaining many commissions from the wealthy citizens of Delft, other Dutch nobles and visiting foreign dignitaries. His portraits display his characteristic dry manner of painting, evident in this work where the pigment has been applied without much oil. The elaborate lace collar and slashed doublet are reminiscent of clothes that appear in Frans Hals's work of the same period. Work in The Usher Gallery (Portrait) Maria Van Wassenaer Hanecops Oil Usher Gallery Rehang 2014 Mary Henrietta Dering Curtois – (1854 - 6 October 1928) About Mary Henrietta Dering Curtois was born at the Longhills, Branston, in 1854 and was the eldest daughter of the late Rev Atwill Curtois (for 21 years Rector of Branston and the fifth of the family to be rector there), and a brother of the Rev Algernon Curtois of Lincoln. -

19TH CENTURY EUROPEAN VICTORIAN and BRITISH IMPRESSIONIST ART Wednesday 14 March 2018

19TH CENTURY EUROPEAN VICTORIAN AND BRITISH IMPRESSIONIST ART Wednesday 14 March 2018 19TH CENTURY EUROPEAN, VICTORIAN AND BRITISH IMPRESSIONIST ART Wednesday 14 March at 2.00pm New Bond Street, London VIEWING BIDS ENQUIRIES PHYSICAL CONDITION OF Friday 9 March +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Peter Rees (Head of Sale) LOTS IN THIS AUCTION 2pm to 5pm +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax +44 (0) 20 7468 8201 Saturday 10 March To bid via the internet please [email protected] PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE IS 11am to 3pm visit bonhams.com NO REFERENCE IN THIS Sunday 11 March Charles O’Brien CATALOGUE TO THE PHYSICAL 11am to 3pm Please note that bids should be (Head of Department) CONDITION OF ANY LOT. Monday 12 March submitted no later than 4pm on +44 (0) 20 7468 8360 INTENDING BIDDERS MUST 9am to 4.30pm the day prior to the sale. New [email protected] SATISFY THEMSELVES AS TO Tuesday 13 March bidders must also provide proof THE CONDITION OF ANY LOT 9am to 4.30pm of identity when submitting bids. Emma Gordon AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE 14 Wednesday 14 March Failure to do this may result in +44 (0) 20 7468 8232 OF THE NOTICE TO BIDDERS 9am to 12pm your bid not being processed. [email protected] CONTAINED AT THE END OF THIS CATALOGUE. SALE NUMBER TELEPHONE BIDDING Alistair Laird 24741 Bidding by telephone will only +44 (0) 20 7468 8211 As a courtesy to intending be accepted on a lot with a [email protected] bidders, Bonhams will provide a CATALOGUE lower estimate of or in written Indication of the physical £25.00 excess of £1,000 Deborah Cliffe condition of lots in this sale if a +44 (0) 20 7468 8337 request is received up to 24 ILLUSTRATIONS Live online bidding is available [email protected] hours before the auction starts.