City Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Special Offer 2

Independent Australian and International titles for your readers New Releases: November 2019 Books for all ages Juno Jones, Mystery Writer (Juno Jones #2) RRP: $12.99 Author: Kate Gordon, Drawings by Sandy Flett Publisher: Yellow Brick Books | Release Date: 01/11/2019 Format: Paperback | Pages: 96 | Size: 12.9 x 19.8 cm DESCRIPTION: Muttonbird Bay Primary is once again under threat of closure, and Juno Jones is pretty sure the Alien Lizard Men are involved. But that’s not all ... Shy Vi is missing, Miss Tippett is acting VERY strangely, and everyone keeps turning to Juno Jones to solve the mysteries. And then, Perfect Paloma suddenly need’s Juno’s help ... ISBN: 9780648492528 To solve these cases Juno Jones will need to be come a Mystery Writer! BISAC: JUVENILE FICTION / Humorous Stories (JUV019000) SPECIAL OFFER 1: 10 PACK + MERCHANDISE RRP: $129.90* | PACK ISBN: 978-0648492535 * This special offer pack of Juno Jones Mystery Writer by CBCA longlisted author Kate Gordon (Girl Running, Boy Falling), includes: 10 books, 1 x poster and 20 temporary Juno Jones tattoos. *Extra 5% discount when you order this pack before 30th September (Not valid with any other offer) SPECIAL OFFER 2 Juno Jones, MIXED PACK Word Ninja: Juno Jones # 1 RRP: $129.90* is also available PACK ISBN: 978-0648492542 separately. This special offer pack includes: RRP: $12.99 ISBN: 9780994557094 x5 Juno Jones Mystery Writer x5 Juno Jones Word Ninja x2 posters (one for each book) 20 temporary tattoos All prices include GST bookstores.novelladistribution.com.au 1 November 2019 Grave Tales: Queensland’s Great South West RRP: $29.95 Author: Helen Goltz, Chris Adams | Publisher: Atlas Productions | Pages: 300 Release Date: 01/11/2019 | Format: Paperback | Size: 15.2 x 22.9 cm DESCRIPTION: Ordinary people caught up in extraordinary events are captured in ‘Grave Tales: Queensland’s Great South West’. -

Jeffrey Steele

Jeffrey Steele RCM Galerie Jeffrey Steele La structure et le rythme La structure et le rythme : sur l’art de Jeffrey Steele Le peintre britannique Jeffrey Steele a été l’une des figures artistiques les plus en vue au sein de ce grand mouvement qui a animé les années 1960, l’art cinétique. Grâce à un seul tableau, peint en 1964, immédiatement devenu l’archétype de ce qu’un journaliste de Time Magazine désigna sous l’abréviation d’ Op Art pour Optical Art, en prenant bien le soin d’annoncer dans le titre de l’article sa teneur : « Pictures that attack the Eye ». Pour l’Amé- rique, le ton était donné. L’oeuvre intitulée Baroque Experiment - Fred Maddox devint tout de suite emblématique de la grande exposition internationale The Responsive Eye, qui fut organisée l’année suivante au Museum of Modern Art à New York par William C. Seitz et qui connut malgré les réserves d’une partie du public et de la presse en général un grand retentissement. Baroque Experiment - Fred Maddox, le tableau de Jeffrey Steele aujourd’hui chez un col- lectionneur brésilien, est en effet exemplaire de son art : abstrait, géométrique, bi-dimen- sionnel, fortement structuré par un ensemble de rectangles concentriques partant du centre et augmentant vers la périphérie, en même temps déstabilisé par le basculement de ses élé- ments dans un sens et dans l’autre. Les espaces ainsi créés se trouvent entièrement occupés d’une même forme en demi - lune répétée dont la hauteur est proportionnelle à la largeur des espaces. Le noyau central quant à lui est tapissé de cercles pleins. -

The Female Art of War: to What Extent Did the Female Artists of the First World War Con- Tribute to a Change in the Position of Women in Society

University of Bristol Department of History of Art Best undergraduate dissertations of 2015 Grace Devlin The Female Art of War: To what extent did the female artists of the First World War con- tribute to a change in the position of women in society The Department of History of Art at the University of Bristol is commit- ted to the advancement of historical knowledge and understanding, and to research of the highest order. We believe that our undergraduates are part of that endeavour. For several years, the Department has published the best of the annual dis- sertations produced by the final year undergraduates in recognition of the excellent research work being undertaken by our students. This was one of the best of this year’s final year undergraduate disserta- tions. Please note: this dissertation is published in the state it was submitted for examination. Thus the author has not been able to correct errors and/or departures from departmental guidelines for the presentation of dissertations (e.g. in the formatting of its footnotes and bibliography). © The author, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means without the prior permission in writing of the author, or as expressly permitted by law. All citations of this work must be properly acknowledged. Candidate Number 53468 THE FEMALE ART OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR 1914-1918 To what extent did the female artists of the First World War contribute to a change in the position of women in society? Dissertation submitted for the Degree of B.A. -

Modern British & Irish

Modern British & Irish Art Tuesday 4 June 2013 at 1pm Knightsbridge, London Modern British & Irish Art Tuesday 4 June 2013 at 1pm Knightsbridge Bonhams Enquiries Please see page 2 for bidder Montpelier Street Emma Corke information including after-sale Knightsbridge +44 (0) 20 7393 3949 collection and shipment London SW7 1HH [email protected] www.bonhams.com Please see back of catalogue Shayn Speed for important notice to bidders Viewing +44 (0) 20 7393 3909 Sunday 2 June 11am to 3pm [email protected] Illustration Monday 3 June 9am to 4.30pm Front cover: Lot 167 Tuesday 4 June 9am to 11am Customer Services Back cover: Lot 19 Monday to Friday 8.30am to 6pm Inside front: Lot 76 Bids +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Inside back: Lot 179 +44 (0) 20 7447 7448 +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax Sale Number: 20777 To bid via the internet please visit www.bonhams.com Catalogue: £12 Please note that bids should be submitted no later than 24 hours before the sale. New bidders must also provide proof of identity when submitting bids. Failure to do this may result in your bids not being processed. Bidding by telephone will only be accepted on a lot with a lower estimate in excess of £400. Live online bidding is available for this sale Please email [email protected] with “Live bidding” in the subject line 48 hours before the auction to register for this service. Bonhams 1793 Limited Bonhams 1793 Ltd Directors Bonhams UK Ltd Directors Registered No. 4326560 Robert Brooks Chairman, Colin Sheaf Deputy Chairman, Colin Sheaf Chairman, Jonathan Baddeley, Antony Bennett, Iain Rushbrook, John Sandon, Tim Schofield, Registered Office: Montpelier Galleries Malcolm Barber Group Managing Director, Matthew Bradbury, Harvey Cammell, Simon Cottle, Veronique Scorer, James Stratton, Roger Tappin, Matthew Girling CEO UK and Europe, Andrew Currie, David Dallas, Paul Davidson, Jean Ghika, Shahin Virani, David Williams, Michael Wynell-Mayow. -

Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 1

Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 1 CHAPTER I. CHAPTER II. CHAPTER III. CHAPTER IV. CHAPTER V. CHAPTER VI. CHAPTER VII. CHAPTER VIII. CHAPTER IX. CHAPTER X. CHAPTER I. CHAPTER II. CHAPTER III. CHAPTER IV. CHAPTER V. CHAPTER VI. CHAPTER VII. CHAPTER VIII. CHAPTER IX. CHAPTER X. Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy The Project Gutenberg EBook of Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 2 License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy Author: George Biddell Airy Release Date: January 9, 2004 [EBook #10655] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SIR GEORGE AIRY *** Produced by Joseph Myers and PG Distributed Proofreaders AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF SIR GEORGE BIDDELL AIRY, K.C.B., M.A., LL.D., D.C.L., F.R.S., F.R.A.S., HONORARY FELLOW OF TRINITY COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE, ASTRONOMER ROYAL FROM 1836 TO 1881. EDITED BY WILFRID AIRY, B.A., M.Inst.C.E. 1896 PREFACE. The life of Airy was essentially that of a hard-working, business man, and differed from that of other hard-working people only in the quality and variety of his work. It was not an exciting life, but it was full of interest, and his work brought him into close relations with many scientific men, and with many men high in the State. -

February, 1955

Library of The Harvard Musical Association Bulletin No. 23 February, 1955 Library Committee CHARLES R. NUTTER JOHN N. BURK RICHARD G. APPEL CYRUS DURGIN RUDOLPH ELIE Director of the Library and Library and Custodian of the Marsh Room Marsh Room Marsh Room CHARLES R. NUTTER MURIEL FRENCH FLORENCE C. ALLEN To the Members of the Association: Your attention is called to an article in this issue by Albert C. Koch. * * * * REPORT ON THE LIBRARY AND ON THE MARSH ROOM FOR THE YEAR 1954 To the President and the Directors of The Harvard Musical Association: Today, when television and the radio, both A.M. and F.M., are providing much of the intellectual sustenance for the common man and woman, the individual who turns for an intellectual repast to the writers of past centuries and also tries to phrase his thoughts both vocal and written with some regard to the rules of grammar and the principles of rhetoric is regarded as high‐brow and is thrown out of society. I am aware that I lay myself open to the charge of being a high‐brow, a charge that creates no reactionary emotion at all, especially as it comes usually from the low‐brow, and that I may be thrown out of society into a lower stratum, when I state that for the text of this report I have turned to a gentleman whose mortal life spanned the years between 1672 and 1719. Even the low‐brow has probably heard or read the name Joseph Addison, though it may convey nothing to him except the fact that it has an English and not a foreign sound. -

Studio International Magazine: Tales from Peter Townsend’S Editorial Papers 1965-1975

Studio International magazine: Tales from Peter Townsend’s editorial papers 1965-1975 Joanna Melvin 49015858 2013 Declaration of authorship I, Joanna Melvin certify that the worK presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this is indicated in the thesis. i Tales from Studio International Magazine: Peter Townsend’s editorial papers, 1965-1975 When Peter Townsend was appointed editor of Studio International in November 1965 it was the longest running British art magazine, founded 1893 as The Studio by Charles Holme with editor Gleeson White. Townsend’s predecessor, GS Whittet adopted the additional International in 1964, devised to stimulate advertising. The change facilitated Townsend’s reinvention of the radical policies of its founder as a magazine for artists with an international outlooK. His decision to appoint an International Advisory Committee as well as a London based Advisory Board show this commitment. Townsend’s editorial in January 1966 declares the magazine’s aim, ‘not to ape’ its ancestor, but ‘rediscover its liveliness.’ He emphasised magazine’s geographical position, poised between Europe and the US, susceptible to the influences of both and wholly committed to neither, it would be alert to what the artists themselves wanted. Townsend’s policy pioneered the magazine’s presentation of new experimental practices and art-for-the-page as well as the magazine as an alternative exhibition site and specially designed artist’s covers. The thesis gives centre stage to a British perspective on international and transatlantic dialogues from 1965-1975, presenting case studies to show the importance of the magazine’s influence achieved through Townsend’s policy of devolving responsibility to artists and Key assistant editors, Charles Harrison, John McEwen, and contributing editor Barbara Reise. -

Secondary and FE Teacher Resource for Teaching Key Stages 3–5 Sculpture in the RA Collection a Sculpture Student at Work in the RA Schools in 1953

Secondary and FE Teacher Resource For teaching key stages 3–5 Sculpture in the RA Collection A sculpture student at work in the RA Schools in 1953. © Estate of Russell Westwood Contents Introduction Illustrated key works with information, quotes, key words, questions, useful links and art activities for the classroom Glossary Further reading To book your visit Email studentgroups@ royalacademy.org.uk or call 020 7300 5995 roy.ac/teachers ‘...we live in a world where images are in abundance and they’re moving, [...] they’re doing all kinds of things, very speedily. Whereas sculpture needs to be given time, you need to just wait with it and become the moving object that it isn’t, so this action between the still and the moving is incredibly demanding for all. ’ Phyllida Barlow RA The Council of the Royal Academy selecting Pictures for the Exhibition, 1875, Russel Cope RA (1876). Photo: John Hammond Introduction What is the Royal Academy of Arts? The Royal Academy (RA) was Every newly elected Royal set up in 1768 and 2018 was Academician donates a work of art, its 250th anniversary. A group of known as a ‘Diploma Work’, to the artists and architects called Royal RA Collection and in return receives Academicians (or RAs) are in charge a Diploma signed by the Queen. The of governing the Academy. artist is now an Academician, an important new voice for the future of There are a maximum of 80 RAs the Academy. at any one time, and spaces for new Members only come up when In 1769, the RA Schools was an existing RA becomes a Senior founded as a school of fine art. -

New Editions 2012

January – February 2013 Volume 2, Number 5 New Editions 2012: Reviews and Listings of Important Prints and Editions from Around the World • New Section: <100 Faye Hirsch on Nicole Eisenman • Wade Guyton OS at the Whitney • Zarina: Paper Like Skin • Superstorm Sandy • News History. Analysis. Criticism. Reviews. News. Art in Print. In print and online. www.artinprint.org Subscribe to Art in Print. January – February 2013 In This Issue Volume 2, Number 5 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On Visibility Associate Publisher New Editions 2012 Index 3 Julie Bernatz Managing Editor Faye Hirsch 4 Annkathrin Murray Nicole Eisenman’s Year of Printing Prodigiously Associate Editor Amelia Ishmael New Editions 2012 Reviews A–Z 10 Design Director <100 42 Skip Langer Design Associate Exhibition Reviews Raymond Hayen Charles Schultz 44 Wade Guyton OS M. Brian Tichenor & Raun Thorp 46 Zarina: Paper Like Skin New Editions Listings 48 News of the Print World 58 Superstorm Sandy 62 Contributors 68 Membership Subscription Form 70 Cover Image: Rirkrit Tiravanija, I Am Busy (2012), 100% cotton towel. Published by WOW (Works on Whatever), New York, NY. Photo: James Ewing, courtesy Art Production Fund. This page: Barbara Takenaga, detail of Day for Night, State I (2012), aquatint, sugar lift, spit bite and white ground with hand coloring by the artist. Printed and published by Wingate Studio, Hinsdale, NH. Art in Print 3500 N. Lake Shore Drive Suite 10A Chicago, IL 60657-1927 www.artinprint.org [email protected] No part of this periodical may be published without the written consent of the publisher. -

A4 Web Map 26-1-12:Layout 1

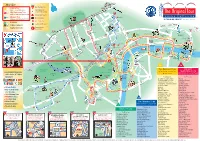

King’s Cross Start St Pancras MAP KEY Eurostar Main Starting Point Euston Original Tour 1 St Pancras T1 English commentary/live guides Interchange Point City Sightseeing Tour (colour denotes route) Start T2 W o Language commentaries plus Kids Club REGENT’S PARK Euston Rd b 3 u Underground Station r n P Madame Tussauds l Museum Tour Russell Sq TM T4 Main Line Station Gower St Language commentaries plus Kids Club q l S “A TOUR DE FORCE!” The Times, London To t el ★ River Cruise Piers ss Gt Portland St tenham Ct Rd Ru Baker St T3 Loop Line Gt Portland St B S s e o Liverpool St Location of Attraction Marylebone Rd P re M d u ark C o fo t Telecom n r h Stansted Station Connector t d a T5 Portla a m Museum Tower g P Express u l p of London e to S Aldgate East Original London t n e nd Pl t Capital Connector R London Wall ga T6 t o Holborn s Visitor Centre S w p i o Aldgate Marylebone High St British h Ho t l is und S Museum el Bank of sdi igh s B tch H Gloucester Pl s England te Baker St u ga Marylebone Broadcasting House R St Holborn ld d t ford A R a Ox e re New K n i Royal Courts St Paul’s Cathedral n o G g of Justice b Mansion House Swiss RE Tower s e w l Tottenham (The Gherkin) y a Court Rd M r y a Lud gat i St St e H n M d t ill r e o xfo Fle Fenchurch St Monument r ld O i C e O C an n s Jam h on St Tower Hill t h Blackfriars S a r d es St i e Oxford Circus n Aldwyc Temple l a s Edgware Rd Tower Hil g r n Reg Paddington P d ve s St The Monument me G A ha per T y Covent Garden Start x St ent Up r e d t r Hamleys u C en s fo N km Norfolk -

Contemporary Art Society Annual Report 1967-68

Front Cover: Henry Moore Knife Edge-Two Piece. Presented to the Nation by the Contemporary Art Society and the artist, 1967. Chairman's Report June 27th 1968 Foundation Collection. Our most recent Patron I have pleasure in presenting my report which covers the Society's activities party at the Tate was held on May 16th to mark the close of the Barbara Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother from June last year until today. Peter Meyer, whom we were very pleased to Hepworth Exhibition. Dame Barbara welcome back on the Committee as was the Guest of Honour, first at a Executive Committee Honorary Treasurer at last year's buffet supper in the restaurant, and later Whitney Straight CBE MC DFC Chairman Annual Meeting, will be dealing with at a party in the Gallery, where Anthony Lousada Vice-Chairman the Society's financial affairs in his hundreds of our members were able to Peter Meyer Honorary Treasurer speech which follows mine and deals meet Dame Barbara and have a last The Hon John Sainsbury Honorary Secretary with our financial year which ended on look at the wonderful exhibition. This G. L. Conran was such a successful evening that we Derek Hill December 31st 1967. As well as welcoming Peter Meyer are very much hoping to repeat one on Bryan Robertson OBE similar lines at the end of the Henry The Hon Michael Astor back to the Committee we were very The Lord Croft happy to elect Joanna Drew, whose Moore Exhibition in September. We are, Alan Bowness knowledge will I am sure be of great as always, most grateful to the Trustees James Melvin value. -

A Survey of Acrylic Sheet in Portuguese Art Collections Levantamento De Obras De Arte Em Chapa Acrílica Em Coleções Portuguesas

ARTICLE / ARTIGO ARTICLE / ARTIGO A survey of acrylic sheet in Portuguese art collections Levantamento de obras de arte em chapa acrílica em coleções Portuguesas Sara Babo1, Joana Lia Ferreira1 1 Department of Conservation and Restoration and Research Unit LAQV-REQUIMTE, NOVA School of Science and Technology (FCT NOVA), 2829-516 Monte da Caparica. *corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Acrylic sheet, also known by the commercial names Plexiglas or Perspex, consists of poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA). Attractive to artists since its development in the 1930s, it became especially popular during the 1960s. In Portugal, knowledge about its use by artists and its condition is scarce. In this work, the main Portuguese art collections were surveyed with the goal of gaining an overview of the use of acrylic sheet in the Portuguese art context and its current condition. The paper describes the methodology used and the results obtained regarding 137 artworks by 69 different artists registered as containing acrylic. Results show that this material is being used by Portuguese artists at least since the 1960s. It has been used in several artistic forms, from painting and sculpture to photography, installation, objects/reliefs, and artist books. Most of the artworks were in good or fair condition. The main problems observed were dust and dirt deposits, abrasion, and scratches. Keywords acrylic; poly(methyl methacrylate); collections survey; condition survey; plastics conservation; contemporary art Resumo A chapa acrílica, também conhecida pelos nomes comerciais Plexiglas ou Perspex, consiste em poli(metacrilato de metilo) (PMMA). Atractiva para os artistas desde o seu desenvolvimento na década de 1930, popularizou-se durante a década de 1960.