Preliminary Study of Three Polynesian Sources For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 3: a Note on Sources

Appendix 3: A Note on Sources There is a wealth of material from which to develop a more comprehensive account of the role played by warfare and coercion during the wars of unification. The unification of the Hawaiian archipelago is particularly well documented because of its relatively late date, the large number of European visitors to the chain who left written accounts about the period of unification, and the recording of Hawaiian sources in the 19th century. Seven groups of sources are available for the study of Hawaiian society up until the death of the first king, Kamehameha I, in 1819: the observations of European visitors to the islands from 1778 until 1819, missionary accounts from 1820 onwards, oral traditions and oral testimony recorded by Hawaiian scholars from the 1830s onwards, ethnographic studies by Europeans from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, 19th-century land records, archaeological remains of Hawaiian culture, and modern scientific studies of the physical environment. The earliest written accounts of Hawaiian society are the journals and logs of various members of Captain James Cook’s third voyage of discovery into the Pacific. Cook made three separate visits to the Hawaiian Islands between January 1778 and February 1779. As a number of Cook’s officers kept journals, it is possible to crosscheck their accounts for inconsistencies.1 The expedition only spent three and a half months in the island chain, mostly on board ship. Only Waimea Bay on Kaua‘i, and Kealakekua Bay on Hawai‘i were visited for any length of time, or described in any detail. -

The Hawaiian Military Transformation from 1770 to 1796

4 The Hawaiian Military Transformation from 1770 to 1796 In How Chiefs Became Kings, Patrick Kirch argues that the Hawaiian polities witnessed by James Cook were archaic states characterised by: the development of class stratification, land alienation from commoners and a territorial system of administrative control, a monopoly of force and endemic conquest warfare, and, most important, divine kingship legitimated by state cults with a formal priesthood.1 The previous chapter questioned the degree to which chiefly authority relied on the consent of the majority based on the belief in the sacred status of chiefs as opposed to secular coercion to enforce compliance. This chapter questions the nature of the monopoly of coercion that Kirch and most commentators ascribed to chiefs. It is argued that military competition forced changes in the composition and tactics of chiefly armies that threatened to undermine the basis of chiefly authority. Mass formations operating in drilled unison came to increasingly figure alongside individual warriors and chiefs’ martial prowess as decisive factors in battle. Gaining military advantage against chiefly rivals came at the price of increasing reliance on lesser ranked members of ones’ own communities. This altered military relationship in turn influenced political and social relations in ways that favoured rule based more on the consent and cooperation of the ruled than the threat of coercion against them for noncompliance. As armies became larger and stayed in the field 1 Kirch (2010), p. 27. 109 TRANSFORMING Hawai‘I longer, the logistics of adequate and predictable agricultural production and supply became increasingly important and the outcome of battles came to be less decisive. -

The Conflict Between Traditional Knowledge and Modernity in the Navigation of Polynesia

Journal of World Anthropology: Occasional Papers: Volume III, Number 2 48 “When earth and sky almost meet”: The Conflict between Traditional Knowledge and Modernity in Polynesian Navigation. Luke Strongman1 Abstract This paper provides an account of the differing ontologies of Polynesian and European navigation techniques in the Pacific. The subject of conflict between traditional knowledge and modernity is examined from nine points of view: The cultural problematics of textual representation, historical differences between European and Polynesian navigation; voyages of re-discovery and re-creation: Lewis and Finney; How the Polynesians navigated in the Pacific; a European history of Polynesian navigation accounts from early encounters; “Earth and Sky almost meet”: Polynesian literary views of recovered knowledge; lost knowledge in cultural exchanges – the parallax view; contemporary views and lost complexities. Introduction Polynesians descended from kinship groups in south-east Asia discovered new islands in the Pacific in the Holocene period, up to 5000 calendar years before the present day. The European voyages of discovery in the Pacific from the eighteenth century, in the Anthropocene era, brought Polynesian and European cultures together, resulting in exchanges that threw their cross-cultural differences into relief. As Bernard Smith suggests: “The scientific examination of the Pacific, by its very nature, depended on the level reached by the art of navigation” (Smith 1985:2). Two very different cultural systems, with different navigational practices, began to interact. 1 The Open Polytechnic of New Zealand Journal of World Anthropology: Occasional Papers: Volume III, Number 2 49 Their varied cultural ontologies were based on different views of society, science, religion, history, narrative, and beliefs about the world. -

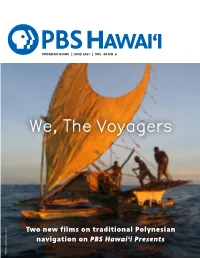

June Program Guide

PROGRAM GUIDE | JUNE 2021 | VOL. 40 NO. 6 Two new films on traditional Polynesian navigation on PBS Hawai‘i Presents Wade Fairley, copyright Vaka Taumako Project Taumako copyright Vaka Fairley, Wade A Long Story That Informed, Influenced STATEWIDE BOARD OF DIRECTORS and Inspired Chair The show’s eloquent description Joanne Lo Grimes nearly says it all… Vice Chair Long Story Short with Leslie Wilcox Jason Haruki features engaging conversations with Secretary some of the most intriguing people in Joy Miura Koerte Hawai‘i and across the world. Guests Treasurer share personal stories, experiences Kent Tsukamoto and values that have helped shape who they are. Muriel Anderson What it does not express is the As we continue to tell stories of Susan Bendon magical presence Leslie brought to Hawai‘i’s rich history, our content Jodi Endo Chai will mirror and reflect our diverse James E. Duffy Jr. each conversation and the priceless communities, past, present and Matthew Emerson collection of diverse voices and Jason Fujimoto untold stories she captured over the future. We are in the process of AJ Halagao years. Former guest Hoala Greevy, redefining some of our current Ian Kitajima Founder and CEO of Paubox, Inc., programs like Nā Mele: Traditions in Noelani Kalipi may have said it best, “Leslie was Hawaiian Song and INSIGHTS ON PBS Kamani Kuala‘au HAWAI‘I, and soon we will announce Theresia McMurdo brilliant to bring all of these pieces Bettina Mehnert of Hawai‘i history together to live the name and concept of a new series. Ryan Kaipo Nobriga forever in one amazing library. -

Agriculture, Power, and Community in Kaupō, Maui

On the Cloak of Kings: Agriculture, Power, and Community in Kaupō, Maui By Alexander Underhill Baer A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Patrick V. Kirch Professor Kent G. Lightfoot Professor Anthony R. Byrne Spring 2015 On the Cloak of Kings: Agriculture, Power, and Community in Kaupō, Maui Copyright © 2015 By Alexander Underhill Baer Table of Contents List of Figures iv List of Tables viii Acknowledgements x CHAPTER I: OPENING THE WATERS OF KAUPŌ Introduction 1 Kaupō’s Natural and Historical Settings 3 Geography and Environment 4 Regional Ethnohistory 5 Plan of the Dissertation 7 CHAPTER 2: UNDERSTANDING KAUPŌ: THEORETICAL APPROACHES TO THE STUDY OF POWER AND PRODUCTION Introduction 9 Last of the Primary States 10 Of Chiefdoms and States 12 Us Versus Them: Evolutionism Prior to 1960 14 The Evolution Revolution: Evolutionism and the New Archaeology 18 Evolution Evolves: Divergent Approaches from the 1990s Through Today 28 Agriculture and Production in the Development of Social Complexity 32 Lay of the Landscape 36 CHAPTER 3: MAPPING HISTORY: KAUPŌ IN MAPS AND THE MAHELE Introduction 39 Social and Spatial Organization in Polynesia 40 Breaking with the Past: New Forms of Social Organization and Land Distribution 42 The Great Mahele 47 Historic Maps of Hawaiʻi and Kaupō 51 Kalama Map, 1838 55 Hawaiian Government Surveys and Maps 61 Post-Mapping: Kaupō Land -

Cooperative Natural Resource and Invasive Species Management in Hawaiʽi

D.C. Duff y and C. Martin Duff y, D.C. and C. Martin. Cooperative Natural Resource and Invasive Species Management in Hawaiʽi Cooperative natural resource and invasive species management in Hawai'i D.C. Duff y1 and C. Martin2 1Pacifi c Cooperative Studies Unit, Department of Botany, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, 3190 Maile Way, Honolulu HI 96822, USA. <dduff [email protected]>. 2Pacifi c Cooperative Studies Unit/Coordinating Group on Alien Pest Species, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, 3190 Maile Way, Honolulu HI 96822, USA. Abstract From the arrival of Polynesians before 1200 AD until Western contact in 1778, Hawaiian land use and resource distribution were centred on the “ahupuaʻa” system of watershed-based management areas that made their inhabitants nearly self-suffi cient. Those units were grouped into larger regions, each called a “moku,” led by lower chiefs who were in turn governed by the high chief or king of each island. While societal and environmental taboo or “kapu” were enforced from above, day to day neighbourhood cooperation served to protect resources, produce food, and sustain up to one million people before Western contact. Following the arrival of Europeans, land and resource management, and governance based on native Hawaiian core beliefs, were replaced by a centralised Western market economy. Modern land ownership, agency mandates and legal jurisdictions provide artifi cial walls that keep people from moving, but do not constrain invasive species, nor are they eff ective for managing public trust resources such as water or native species. Over time government and conservation organisations have come to view decentralised cooperation as a key to protecting the 50% of Hawaiian terrestrial, native habitat that persists. -

The Laterwriting of Abraham Fornander, 1870-1887 A

523 UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'llIBRARY "A TRUSTWORTHY HISTORICAL RECORD": THE LATERWRITING OF ABRAHAM FORNANDER, 1870-1887 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF EDUCATION IN EDUCATIONAL FOUNDATIONS MAY 2004 By Pamela Haight Thesis Committee: Eileen Tamura, Chairperson Gay Garland Reed Vilsoni Hereniko ABSTRACT Using a post-colonial framework, this thesis examines the later research and writing ofAbraham Fornander. The paper addresses the politics, religion, and society that informed Fornander's research and writing, then focuses more closely on his book, An Account ofthe Polynesian Race and international response to it. Fornander's tenacity in promoting his Western worldview and his efforts to advance his career infused his writings and, in the end, served to overshadow existing indigenous language and culture, hastening deterioration ofboth. Utilizing correspondence, early writing for newspapers, and other archival information, the paper demonstrates his attempts to attain authentic status for himselfand his work. Though inconclusive in terms ofproving Fornander's complicity with colonialism, the thesis presents another viewing ofone man's work and begs a previously hidden discussion. 111 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Purpose ofthe study 7 Methodology 10 Background to the study 13 Language and Colonization , 15 Representing Others 17 Collecting Cultures 21 19th Century Hawai'i 25 Abraham Fomander 30 Fomander's Newswriting 34 Fomander's Philological Research 50 Response to An Account ofthe Polynesian Race 61 Discussion and implications 75 Postscript 78 Appendix A: Letter from Rollin Daggett to Abraham Fomander 82 Appendix B: Letter from Abraham Fomander to Rollin Daggett. -

A Brief History of the Hawaiian People

0 A BRIEF HISTORY OP 'Ill& HAWAIIAN PEOPLE ff W. D. ALEXANDER PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE HAWAIIAN KINGDOM NEW YORK,: . CINCINNATI•:• CHICAGO AMERICAN BOOK C.OMPANY Digitized by Google ' .. HARVARD COLLEGELIBRAllY BEQUESTOF RCLANOBUr.ll,' , ,E DIXOII f,'.AY 19, 1936 0oPYBIGRT, 1891, BY AlilBIOAN BooK Co)[PA.NY. W. P. 2 1 Digit zed by Google \ PREFACE AT the request of the Board of Education, I have .fi. endeavored to write a simple and concise history of the Hawaiian people, which, it is hoped, may be useful to the teachers and higher classes in our schools. As there is, however, no book in existence that covers the whole ground, and as the earlier histories are entirely out of print, it has been deemed best to prepare not merely a school-book, but a history for the benefit of the general public. This book has been written in the intervals of a labo rious occupation, from the stand-point of a patriotic Hawaiian, for the young people of this country rather than for foreign readers. This fact will account for its local coloring, and for the prominence given to certain topics of local interest. Especial pains have been taken to supply the want of a correct account of the ancient civil polity and religion of the Hawaiian race. This history is not merely a compilation. It is based upon a careful study of the original authorities, the writer having had the use of the principal existing collections of Hawaiian manuscripts, and having examined the early archives of the government, as well as nearly all the existing materials in print. -

Tables of Contents of the Hawaiian Journal of History Volumes 1-35

Tables of Contents of The Hawaiian Journal of History Volumes 1-35 1967-2001 TABLES OF CONTENTS * VOLUMES I-35 * I967-2OOI Volume 1 • 1967 Dr. Edward Arning, the First Microbiologist in Hawaii 3 by O. A. Bushnell The Decline of Puritanism at Honolulu in the Nineteenth Century 31 by Gavan Daws Charles de Varigny's Tall Tale of Jack Purdy and the Wild Bull 43 by Alfons L. Korn Here Lies History: Oahu Cemetery, a Mirror of Old Honolulu 53 by Richard A. Greer Movies in Hawaii, 1897-1932 63 by Robert C. Schmitt That Old-Time Portuguese Bread 83 by Manuel G. Jardin A Case of Eye Trouble 87 by Richard A. Greer Volume 2 • 1968 A Sketch of Ke-Kua-Nohu, 1845-1850, with Notes of Other Times Before and After 3 by Richard A. Greer Memoirs of Thomas Hopoo 42 The Attempt to Lay a Cable between the Hawaiian Islands 55 by Ann Hamilton Stites The Wreck of the "Philosopher" Helvetius 69 by Helen P. Hoyt The United States Leprosy Investigation Station at Kalawao 76 by O. A. Bushnell The Lahainaluna Money Forgeries 95 by Peter Morse The Sandwich Islands, from Richard Brinsley Hinds' Journal of the Voyage of the Sulphur (1836-1842) 102 transcribed and edited by E. Alison Kay The Publications of Ralph S. Kuykendall 136 compiled by Delman L. Kuykendall and Charles H. Hunter Cunha's Alley—The Anatomy of a Landmark 142 by Richard A. Greer and others The Japanese in Hawaii, 1868-1967: A Bibliography of the First Hundred Years 153 reviewed by Shunzo Sakamaki 203 INDEX TO THE HAWAIIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY Volume 3 • 1969 Princess Nahienaena 3 by Marjorie Sinclair Hawaiian Registered Vessels 31 by Agnes C. -

A Portrait of EMMA KAʻILIKAPUOLONO METCALF

HĀNAU MA KA LOLO, FOR THE BENEFIT OF HER RACE: a portrait of EMMA KAʻILIKAPUOLONO METCALF BECKLEY NAKUINA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HAWAIIAN STUDIES AUGUST 2012 By Jaime Uluwehi Hopkins Thesis Committee: Jonathan Kamakawiwoʻole Osorio, Chairperson Lilikalā Kameʻeleihiwa Wendell Kekailoa Perry DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to Kanalu Young. When I was looking into getting a graduate degree, Kanalu was the graduate student advisor. He remembered me from my undergrad years, which at that point had been nine years earlier. He was open, inviting, and supportive of any idea I tossed at him. We had several more conversations after I joined the program, and every single one left me dizzy. I felt like I had just raced through two dozen different ideas streams in the span of ten minutes, and hoped that at some point I would recognize how many things I had just learned. I told him my thesis idea, and he went above and beyond to help. He also agreed to chair my committee. I was orignally going to write about Pana Oʻahu, the stories behind places on Oʻahu. Kanalu got the Pana Oʻahu (HWST 362) class put back on the schedule for the first time in a few years, and agreed to teach it with me as his assistant. The next summer, we started mapping out a whole new course stream of classes focusing on Pana Oʻahu. But that was his last summer. -

Table 4. Hawaiian Newspaper Sources

OCS Study BOEM 2017-022 A ‘Ikena I Kai (Seaward Viewsheds): Inventory of Terrestrial Properties for Assessment of Marine Viewsheds on the Main Eight Hawaiian Islands U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Pacific OCS Region August 18, 2017 Cover image: Viewshed among the Hawaiian Islands. (Trisha Kehaulani Watson © 2014 All rights reserved) OCS Study BOEM 2017-022 Nā ‘Ikena I Kai (Seaward Viewsheds): Inventory of Terrestrial Properties for Assessment of Marine Viewsheds on the Eight Main Hawaiian Islands Authors T. Watson K. Ho‘omanawanui R. Thurman B. Thao K. Boyne Prepared under BOEM Interagency Agreement M13PG00018 By Honua Consulting 4348 Wai‘alae Avenue #254 Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96816 U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Pacific OCS Region August 18, 2016 DISCLAIMER This study was funded, in part, by the US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Environmental Studies Program, Washington, DC, through Interagency Agreement Number M13PG00018 with the US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of National Marine Sanctuaries. This report has been technically reviewed by the ONMS and the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) and has been approved for publication. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the US Government, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. REPORT AVAILABILITY To download a PDF file of this report, go to the US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Environmental Studies Program Information System website and search on OCS Study BOEM 2017-022. -

The Vaeakau-Taumako Wind Compass: a Cognitive Construct for Navigation in the Pacific

THE VAEAKAU-TAUMAKO WIND COMPASS: A COGNITIVE CONSTRUCT FOR NAVIGATION IN THE PACIFIC A thesis submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Cathleen Conboy Pyrek May 2011 Thesis written by Cathleen Conboy Pyrek B.S., The University of Texas at El Paso, 1982 M.B.A., The University of Colorado, 1995 M.A., Kent State University, 2011 Approved by , Advisor Richard Feinberg, Ph.D. , Chair, Department of Anthropology Richard Meindl, Ph.D. , Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Timothy Moerland, Ph.D. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES .............................................................................................................v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... vi CHAPTER I. Introduction ........................................................................................................1 Statement of Purpose .........................................................................................1 Cognitive Constructs ..........................................................................................3 Non Instrument Navigation................................................................................7 Voyaging Communities ...................................................................................11 Taumako ..........................................................................................................15 Environmental Factors .....................................................................................17