Table 4. Hawaiian Newspaper Sources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

78Th Song Contest Program

Celebrating the Music of HH elenelen DD eshaesha BB eamereamer The 78th Anniversary of the Kamehameha of Song Contest Schools The 78th Anniversary March 24, 2000 7:30 p.m. Neal S. Blaisdell Center Honolulu, Hawai‘i Center Honolulu, Neal S. Blaisdell March 24, 2000 7:30 p.m. Helen Desha Beamer How do you pass the time when you’re on a long Helen’s stunning musical talent was evident early “Early on, grandma taught us to run movies When she would play the piano and sing, the ride to visit a friend? If you are Helen Desha in her life. When she was a young student at [in our heads] as we sing the songs or dance the canaries in the birdcage would also chirp and Beamer, you may decide to compose a song, com- Kamehameha School for Girls, her music teacher, hulas. And then you're in that moment and giv- sing. Whenever family, friends or anyone else plete with music and lyrics. A friend, Annabelle Cordelia Clymer, noted in a music program annu- ing everything of yourself. You know what the came over to the house to visit, there would be words mean and you see everything as you’re lots of singing and dancing. We were taught the Ruddle, described such a trip in a letter. al report that “In piano music, there has been singing it. In this way you express it as beauti- love of our family and friends, our Hawaiian splendid advancement on the part of. .Helen fully as you can.” heritage, respect for ourselves and our elders as “Helen was in my station wagon when she Desha, a future composer and player. -

Hawaii Been Researched for You Rect Violation of Copyright Already and Collected Into Laws

COPYRIGHT 2003/2ND EDITON 2012 H A W A I I I N C Historically Speaking Patch Program ABOUT THIS ‘HISTORICALLY SPEAKING’ MANUAL PATCHWORK DESIGNS, This manual was created Included are maps, crafts, please feel free to contact TABLE OF CONTENTS to assist you or your group games, stories, recipes, Patchwork Designs, Inc. us- in completing the ‘The Ha- coloring sheets, songs, ing any of the methods listed Requirements and 2-6 waii Patch Program.’ language sheets, and other below. Answers educational information. Manuals are books written These materials can be Festivals and Holidays 7-10 to specifically meet each reproduced and distributed 11-16 requirement in a country’s Games to the individuals complet- patch program and help ing the program. Crafts 17-23 individuals earn the associ- Recipes 24-27 ated patch. Any other use of these pro- grams and the materials Create a Book about 28-43 All of the information has contained in them is in di- Hawaii been researched for you rect violation of copyright already and collected into laws. Resources 44 one place. Order Form and Ship- 45-46 If you have any questions, ping Chart Written By: Cheryle Oandasan Copyright 2003/2012 ORDERING AND CONTACT INFORMATION SPECIAL POINTS OF INTEREST: After completing the ‘The Patchwork Designs, Inc. Using these same card types, • Celebrate Festivals Hawaii Patch Program’, 8421 Churchside Drive you may also fax your order to Gainesville, VA 20155 (703) 743-9942. • Color maps and play you may order the patch games through Patchwork De- Online Store signs, Incorporated. You • Create an African Credit Card Customers may also order beaded necklace. -

Grand Circle Island (8 Hours)

Royal Star® Deluxe Tour – Exclusive 2019 RSTE3 Grand Circle Island (8 Hours) ® On-Time Guarantee 100% Seat Belted & DriveCam-Equipped 15-Minute Increment Charge Suggested Retail Price / Minimum • $105.00 per person / Minimum of 30 persons • Additional usage fee applies for some hotels. Description Discover O'ahu all in one day, where this 8-hour Grand Circle Island Tour takes you to beautiful scenic spots and hard to get to places with a Royal Star deluxe vehicle and professional driver guide. The tour covers all the beautiful scenic spots including Diamond Head and the Kahala Gold Coast to marine sanctuary Hanauma Bay, natural wonder Halona Blow Hole, lush rainforest Nuuanu Pali and world- famous North Shore surfing beaches. Plus, you'll have enough time (90 minutes) to browse through unique shops in Haleiwa Town. Completing the tour is a visit to O'ahu's historical sites from Dole Plantation to Downtown Honolulu. Our unparalleled Royal Star® deluxe service features the comfort of a Royal Star® Deluxe Gold Motorcoach with seat belt and restroom, plus professional and friendly Royal Star® driver guide and mint and hand towelette service. Includes • All Scenic Spots and Drive: Diamond Head, Hanauma Bay, Halona Blow Hole and Nuuanu Pali (parking fee included). • Hard-to-Get-to Places: World-famous North Shore beaches and Haleiwa town. • Historical Sites: Dole Plantation to Downtown Honolulu. • Deluxe Gold Motorcoach: equipped with seat belt, onboard restroom, digital signage, kneeling feature, air-conditioning, adjustable headrest, footrest and more. • Royal Star driver guide: Professional driver trained to the highest standard (see our testimonials on TripAdvisor), not only for in-depth narration but also to assist you at each stop. -

The Hawaiian Military Transformation from 1770 to 1796

4 The Hawaiian Military Transformation from 1770 to 1796 In How Chiefs Became Kings, Patrick Kirch argues that the Hawaiian polities witnessed by James Cook were archaic states characterised by: the development of class stratification, land alienation from commoners and a territorial system of administrative control, a monopoly of force and endemic conquest warfare, and, most important, divine kingship legitimated by state cults with a formal priesthood.1 The previous chapter questioned the degree to which chiefly authority relied on the consent of the majority based on the belief in the sacred status of chiefs as opposed to secular coercion to enforce compliance. This chapter questions the nature of the monopoly of coercion that Kirch and most commentators ascribed to chiefs. It is argued that military competition forced changes in the composition and tactics of chiefly armies that threatened to undermine the basis of chiefly authority. Mass formations operating in drilled unison came to increasingly figure alongside individual warriors and chiefs’ martial prowess as decisive factors in battle. Gaining military advantage against chiefly rivals came at the price of increasing reliance on lesser ranked members of ones’ own communities. This altered military relationship in turn influenced political and social relations in ways that favoured rule based more on the consent and cooperation of the ruled than the threat of coercion against them for noncompliance. As armies became larger and stayed in the field 1 Kirch (2010), p. 27. 109 TRANSFORMING Hawai‘I longer, the logistics of adequate and predictable agricultural production and supply became increasingly important and the outcome of battles came to be less decisive. -

Ioptron AZ Mount Pro Altazimuth Mount Instruction

® iOptron® AZ Mount ProTM Altazimuth Mount Instruction Manual Product #8900, #8903 and #8920 This product is a precision instrument. Please read the included QSG before assembling the mount. Please read the entire Instruction Manual before operating the mount. If you have any questions please contact us at [email protected] WARNING! NEVER USE A TELESCOPE TO LOOK AT THE SUN WITHOUT A PROPER FILTER! Looking at or near the Sun will cause instant and irreversible damage to your eye. Children should always have adult supervision while observing. 2 Table of Content Table of Content ......................................................................................................................................... 3 1. AZ Mount ProTM Altazimuth Mount Overview...................................................................................... 5 2. AZ Mount ProTM Mount Assembly ........................................................................................................ 6 2.1. Parts List .......................................................................................................................................... 6 2.2. Identification of Parts ....................................................................................................................... 7 2.3. Go2Nova® 8407 Hand Controller .................................................................................................... 8 2.3.1. Key Description ....................................................................................................................... -

09 1Bkrv.Donaghy.Pdf

book reviews 159 References Bickerton, Derek, and William H. Wilson. 1987. “Pidgin Hawaiian.” In Pidgin and Creole Lan- guages: Essays in Memory of John E. Reinecke, edited by Glenn G. Gilbert. Honolulu: Uni- versity of Hawai‘i Press. Drechsel, Emanuel J. 2014. Language Contact in the Early Colonial Pacific: Maritime Polynesian Pidgin before Pidgin English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Massam, Diane. 2000. “VSO and VOS: Aspects of Niuean Word Order.” In The Syntax of Verb Initial Languages, 97–117. Edited by Andrew Carnie and Eithne Guilfoyle. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Roberts, [S.] J. M. 1995. “Pidgin Hawaiian: A Sociohistorical Study.” Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages 10: 1–56. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing. Romaine, Suzanne. 1988. Pidgin and Creole Languages. London: Longman. Hawaiian Music and Musicians (Ka Mele Hawai‘i A Me Ka Po‘e Mele): An Encyclopedic History, Second Edition. Edited by Dr. George S. Kanahele, revised and updated by John Berger. Honolulu: Mutual Publishing, 2012. xlix + 926 pp. Illus- trated. Appendix. Addendum. Index. $35.00 paper ‘Ōlelo Hō‘ulu‘ulu / Summary Ua puka maila ke pa‘i mua ‘ana o Hawaiian Music and Musicians ma ka MH 1979. ‘O ka hua ia o ka noi‘i lō‘ihi ma nā makahiki he nui na ke Kauka George S. Kanahele, ko The Hawaiian Music Foundation, a me nā kānaka ‘ē a‘e ho‘i he lehulehu. Ma ia puke nō i noelo piha mua ‘ia ai ka puolo Hawai‘i, me ka mana‘o, na ia puke nō e ho‘olako mai i ka nele o ka ‘ike pa‘a e pili ana i ka puolo Hawai‘i, kona mo‘olelo, kona mohala ‘ana a‘e, nā mea ho‘okani a pu‘ukani kaulana, a me nā kānaka kāko‘o pa‘a ma hope ona. -

Ka'u Coast, Island of Hawai'i Reconnaissance Survey

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Pacific West Region, Honolulu Office Ka‘u Coast, Island of Hawai‘i Reconnaissance Survey DEDICATION Ka‘ū, hiehie i ka makani. Ka‘ū, regal in the gales. An expression of admiration for the district of Ka‘ū, or for a stately or outstanding person of that district (Mary Kawena Pukui, ‘Ōlelo No‘eau, 1983) In memory of Jimmyleen Keolalani Hanoa (1960-2006). Her life and work as a visionary leader in the Hawaiian community of Ka‘ū, and her roles as mother, friend and facilitator for cultural education programs, live on. We are all better people for having her present in our lives and having had the opportunity of a lifetime, to share her knowledge and aloha. Mahalo, me ke aloha pumehana. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 SUMMARY………………………………………………………………………………. 1 2 BACKGROUND………………………………………………………………………….2 2.1 Background of the Study…………………………………………………………………..……… 2 2.2 Purpose and Scope of the Study Document…………………………….……………………… 2 2.3 Evaluation Criteria…………………………………………....................................................... 3 2.3.1 National Significance……………………………………………………..……………… 3 2.3.2 Suitability………………………………………………………………………………….. 5 2.3.3 Feasibility…………………………………………………………………………………. 5 2.3.4 Management Options…………………………………………………….……………… 5 3 DESCRIPTION OF THE STUDY AREA………………………………………………6 3.1 Regional Context………………………………………………………………………………….. 6 3.2 Location and Maps………………………………………………………………………………… 7 3.3 Land Use and Ownership………………………………………………………………….……… 8 3.4 Resources………………………………………………………………….……………………… 10 3.4.1 Geology and Soils……………………………………………………….……………… 10 3.4.2 Vegetation………………………………………………………………...……………... 12 3.4.3 Wildlife………………………………………………………...................………………13 3.4.4 Marine Resources……………………………………………………….……………… 16 3.4.5 Pools, Ponds and Estuaries…………………………………………………………….18 3.4.6 Cultural and Archeological Resources……………………………………………….. 20 3.4.7 Recreational Resources and Community Use………………………………………. -

HAWAII National Park HAWAIIAN ISLANDS

HAWAII National Park HAWAIIAN ISLANDS UNITED STATES RAILROAD ADMINISTRATION N AT IONAL PAR.K. SERIES n A 5 o The world-famed volcano of Kilauea, eight miles in circumference An Appreciation of the Hawaii National Park By E. M. NEWMAN, Traveler and Lecturer Written Especially for the United States Railroad Administration §HE FIRES of a visible inferno burning in the midst of an earthly paradise is a striking con trast, afforded only in the Hawaii National Park. It is a combination of all that is terrify ing and all that is beautiful, a blending of the awful with the magnificent. Lava-flows of centuries are piled high about a living volcano, which is set like a ruby in an emer ald bower of tropical grandeur. Picture a perfect May day, when glorious sunshine and smiling nature combine to make the heart glad; then multiply that day by three hundred and sixty-five and the result is the climate of Hawaii. Add to this the sweet odors, the luscious fruits, the luxuriant verdure, the flowers and colorful beauty of the tropics, and the Hawaii National Park becomes a dreamland that lingers in one's memory as long as memory survives. Pa ae three To the American People: Uncle Sam asks you to be his guest. He has prepared for you the choice places of this continent—places of grandeur, beauty and of wonder. He has built roads through the deep-cut canyons and beside happy streams, which will carry you into these places in comfort, and has provided lodgings and food in the most distant and inaccessible places that you might enjoy yourself and realize as little as possible the rigors of the pioneer traveler's life. -

Agriculture, Power, and Community in Kaupō, Maui

On the Cloak of Kings: Agriculture, Power, and Community in Kaupō, Maui By Alexander Underhill Baer A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Patrick V. Kirch Professor Kent G. Lightfoot Professor Anthony R. Byrne Spring 2015 On the Cloak of Kings: Agriculture, Power, and Community in Kaupō, Maui Copyright © 2015 By Alexander Underhill Baer Table of Contents List of Figures iv List of Tables viii Acknowledgements x CHAPTER I: OPENING THE WATERS OF KAUPŌ Introduction 1 Kaupō’s Natural and Historical Settings 3 Geography and Environment 4 Regional Ethnohistory 5 Plan of the Dissertation 7 CHAPTER 2: UNDERSTANDING KAUPŌ: THEORETICAL APPROACHES TO THE STUDY OF POWER AND PRODUCTION Introduction 9 Last of the Primary States 10 Of Chiefdoms and States 12 Us Versus Them: Evolutionism Prior to 1960 14 The Evolution Revolution: Evolutionism and the New Archaeology 18 Evolution Evolves: Divergent Approaches from the 1990s Through Today 28 Agriculture and Production in the Development of Social Complexity 32 Lay of the Landscape 36 CHAPTER 3: MAPPING HISTORY: KAUPŌ IN MAPS AND THE MAHELE Introduction 39 Social and Spatial Organization in Polynesia 40 Breaking with the Past: New Forms of Social Organization and Land Distribution 42 The Great Mahele 47 Historic Maps of Hawaiʻi and Kaupō 51 Kalama Map, 1838 55 Hawaiian Government Surveys and Maps 61 Post-Mapping: Kaupō Land -

SCALES! Fast-Flyin- Increasing the to the Consumer Washisoto.N, March the Riciimo.Id

Tbe Exceptions. that be breaks ilown the iiistrmiii lit' your 1 osoin, on whom you h.,ve lav- A SKHMOX TO CAMHLEIiS TllK LKVKK IillOKlJ He T lisd a orheme no the fellow eonlt Owlnosvlll6OutlooK. tiod never made a man strong dough ished nil the favors of your ilccliniutf make 10.in) as easily a turning over hi to endure the wear nnd tear of gam- years. Hut should n feeling of joy w m band, but the fnol wouldn't go into it. Withering Influ- D. & BST1LU Blight and Pernicious bling excitements. for u moment spring iiii in your And Sh.iwneetown, III., is Under From She Then a fool and hi money are nor rubtlsucr. always ences of the Gaming Table. A man In- INTERESTING STATE NEWS. n easily parted after all. Yonkera young having suddenly hearts when you should receive this Twenty or Thirty Feet of Water. Statesman. OWINiJSVIM.E. : KEXTUt KV herited a large property, sits at the from me cherish it not. 1 have fallen 4ft - tim s,, hazard tables uud takes up in a dice deep, never to rise. Those gray 5naKrtlaa- m Remedy. Oiher t ice ttdaona and Itanventna, Ilvrr Two lliinrirrtl l.lvist Vrr l.in.1 lly th it Olht-- r Inix the estate won by a life- 1 should have honored .lamr I'm at a loss to know what nod Ni Take on hit Many Al- father's hairs, that Nitililfn tif llmi Mr. I tliintimcht ttslfnt- to tlo for mv hiisliund: he suffers owwa.wVi luring l iirnts IMrtture liy Krv. -

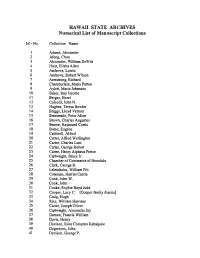

HAWAII STATE ARCHIVES Numerical List of Manuscript Collections

HAWAII STATE ARCHIVES Numerical List of Manuscript Collections M-No. Collection Name 1 Adams, Alexander 2 Afong, Chun 3 Alexander, WilliamDe Witt 4 Hunt, Elisha Allen 5 Andrews, Lorrin 6 Andrews, Robert Wilson 7 Armstrong,Richard 8 Chamberlain, MariaPatton 9 Aylett, Marie Johannes 10 Baker, Ray Jerome 11 Berger, Henri 12 Colcord, John N. 13 Hughes, Teresa Bowler 14 Briggs, Lloyd Vernon 15 Brinsmade, Peter Allen 16 Brown, CharlesAugustus 17 Brown, Raymond Curtis 18 Burns, Eugene 19 Caldwell, Alfred 20 Carter, AlfredWellington 21 Carter,Charles Lunt 22 Carter, George Robert 23 Carter, Henry Alpheus Pierce 24 Cartwright, Bruce Jr. 25 Chamber of Commerce of Honolulu 26 Clark, George R. 27 Leleiohoku, William Pitt 28 Coleman, HarrietCastle 29 Cook, John W. 30 Cook, John 31 Cooke, Sophie Boyd Judd 32 Cooper, Lucy C. [Cooper family diaries] 33 Craig, Hugh 34 Rice, William Harrison 35 Carter,Joseph Oliver 36 Cartwright,Alexander Joy 37 Damon, Francis William 38 Davis, Henry 39 Davison, Rose Compton Kahaipule 40 Degreaves, John 41 Denison, George P. HAWAIi STATE ARCHIVES Numerical List of Manuscript collections M-No. Collection Name 42 Dimond, Henry 43 Dole, Sanford Ballard 44 Dutton, Joseph (Ira Barnes) 45 Emma, Queen 46 Ford, Seth Porter, M.D. 47 Frasher, Charles E. 48 Gibson, Walter Murray 49 Giffard, Walter Le Montais 50 Whitney, HenryM. 51 Goodale, William Whitmore 52 Green, Mary 53 Gulick, Charles Thomas 54 Hamblet, Nicholas 55 Harding, George 56 Hartwell,Alfred Stedman 57 Hasslocher, Eugen 58 Hatch, FrancisMarch 59 Hawaiian Chiefs 60 Coan, Titus 61 Heuck, Theodor Christopher 62 Hitchcock, Edward Griffin 63 Hoffinan, Theodore 64 Honolulu Fire Department 65 Holt, John Dominis 66 Holmes, Oliver 67 Houston, Pinao G. -

Strike Keeps Student-Teachers Home by EILEEN STUDNICKY Inside When the New Castle County Teachers

Voi.102,No. 13 UNIVERSITY OF DELAWARE, NEWARK. DEL Friday. October 20. 1978 I On the Strike Keeps Student-Teachers Home By EILEEN STUDNICKY Inside When the New Castle County teachers . decided to walk off of their jobs on Monday, . they not only held up education for elemen tary and high school students; 122 universi Shockley ty seniors student-teaching this semester are sitting at home too. ~t' Has Spoken "Students do not ~ross picket lines, ac ~ cording to university policy," said Director ,;'3\ But the crowd was more of Clinical Studies Angela B. Case. entertaining than the lecture The university's regulation concerning ....................... p. 3 teacher strikes states: "If the strike is not settled within five teaching days, the University of Delaware will remove the , student teachers and place them in another district for the duration of the s~mester." Nixon Nixon Because of· the problems involved in Many Republican candidates transferring student-teachers from district to district, Case said she will begin don't want the former Presi· transferring them October 30, ten days dent campaigning for them after the strike began. "We are gearing up ....................... p. 7 so that if things are not settled within ten days these students will have placement," she said. Since the strike began student-~eachers at , the elementary school level have been tak You Are What ing seminars that would otherwise have been spread over the course of the You Eat semester, according to Case. Most students who will teach in secon· And UD students should all dary schools are taking exams this week, be extras in the movie according to Dr.