Swans Are Black in the Dark How the Short-Term Focus of Financial Analysis Does Not Shed Light on Long Term Risks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grade 6 Reading Student At–Home Activity Packet

Printer Warning: This packet is lengthy. Determine whether you want to print both sections, or only print Section 1 or 2. Grade 6 Reading Student At–Home Activity Packet This At–Home Activity packet includes two parts, Section 1 and Section 2, each with approximately 10 lessons in it. We recommend that your student complete one lesson each day. Most lessons can be completed independently. However, there are some lessons that would benefit from the support of an adult. If there is not an adult available to help, don’t worry! Just skip those lessons. Encourage your student to just do the best they can with this content—the most important thing is that they continue to work on their reading! Flip to see the Grade 6 Reading activities included in this packet! © 2020 Curriculum Associates, LLC. All rights reserved. Section 1 Table of Contents Grade 6 Reading Activities in Section 1 Lesson Resource Instructions Answer Key Page 1 Grade 6 Ready • Read the Guided Practice: Answers will vary. 10–11 Language Handbook, Introduction. Sample answers: Lesson 9 • Complete the 1. Wouldn’t it be fun to learn about Varying Sentence Guided Practice. insect colonies? Patterns • Complete the 2. When I looked at the museum map, Independent I noticed a new insect exhibit. Lesson 9 Varying Sentence Patterns Introduction Good writers use a variety of sentence types. They mix short and long sentences, and they find different ways to start sentences. Here are ways to improve your writing: Practice. Use different sentence types: statements, questions, imperatives, and exclamations. Use different sentence structures: simple, compound, complex, and compound-complex. -

Carol Raskin

Carol Raskin Artistic Images Make-Up and Hair Artists, Inc. Miami – Office: (305) 216-4985 Miami - Cell: (305) 216-4985 Los Angeles - Office: (310) 597-1801 FILMS DATE FILM DIRECTOR PRODUCTION ROLE 2019 Fear of Rain Castille Landon Pinstripe Productions Department Head Hair (Kathrine Heigl, Madison Iseman, Israel Broussard, Harry Connick Jr.) 2018 Critical Thinking John Leguizamo Critical Thinking LLC Department Head Hair (John Leguizamo, Michael Williams, Corwin Tuggles, Zora Casebere, Ramses Jimenez, William Hochman) The Last Thing He Wanted Dee Rees Elena McMahon Productions Additional Hair (Miami) (Anne Hathaway, Ben Affleck, Willem Dafoe, Toby Jones, Rosie Perez) Waves Trey Edward Shults Ultralight Beam LLC Key Hair (Sterling K. Brown, Kevin Harrison, Jr., Alexa Demie, Renee Goldsberry) The One and Only Ivan Thea Sharrock Big Time Mall Productions/Headliner Additional Hair (Bryan Cranston, Ariana Greenblatt, Ramon Rodriguez) (U. S. unit) 2017 The Florida Project Sean Baker The Florida Project, Inc. Department Head Hair (Willem Dafoe, Bria Vinaite, Mela Murder, Brooklynn Prince) Untitled Detroit City Yann Demange Detroit City Productions, LLC Additional Hair (Miami) (Richie Merritt Jr., Matthew McConaughey, Taylour Paige, Eddie Marsan, Alan Bomar Jones) 2016 Baywatch Seth Gordon Paramount Worldwide Additional Hair (Florida) (Dwayne Johnson, Zac Efron, Alexandra Daddario, David Hasselhoff) Production, Inc. 2015 The Infiltrator Brad Furman Good Films Production Department Head Hair (Bryan Cranston, John Leguizamo, Benjamin Bratt, Olympia -

BROKEN PROMISES: Continuing Federal Funding Shortfall for Native Americans

U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS BROKEN PROMISES: Continuing Federal Funding Shortfall for Native Americans BRIEFING REPORT U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS Washington, DC 20425 Official Business DECEMBER 2018 Penalty for Private Use $300 Visit us on the Web: www.usccr.gov U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS MEMBERS OF THE COMMISSION The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights is an independent, Catherine E. Lhamon, Chairperson bipartisan agency established by Congress in 1957. It is Patricia Timmons-Goodson, Vice Chairperson directed to: Debo P. Adegbile Gail L. Heriot • Investigate complaints alleging that citizens are Peter N. Kirsanow being deprived of their right to vote by reason of their David Kladney race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national Karen Narasaki origin, or by reason of fraudulent practices. Michael Yaki • Study and collect information relating to discrimination or a denial of equal protection of the laws under the Constitution Mauro Morales, Staff Director because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin, or in the administration of justice. • Appraise federal laws and policies with respect to U.S. Commission on Civil Rights discrimination or denial of equal protection of the laws 1331 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or Washington, DC 20425 national origin, or in the administration of justice. (202) 376-8128 voice • Serve as a national clearinghouse for information TTY Relay: 711 in respect to discrimination or denial of equal protection of the laws because of race, color, www.usccr.gov religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin. • Submit reports, findings, and recommendations to the President and Congress. -

Air Line Pilots Page 5 Association, International Our Skies

March 2015 ALSO IN THIS ISSUE: » Landing Your » Known Crewmember » Sleep Apnea Air Dream Job page 20 page 29 Update page 28 Line PilOt Safeguarding Official Journal of the Air Line Pilots page 5 Association, International Our Skies Follow us on Twitter PRINTED IN THE U.S.A. @wearealpa Sponsored Airline- Career Track ATP offers the airline pilot career training solution with a career track from zero time to 1500 hours sponsored by ATP’s airline alliances. Airline Career month FAST TRACK Demand for airline pilots and ATP graduates is soaring, Pilot Program with the “1500 hour rule” and retirements at the majors. AIRLINES Airlines have selected ATP as a preferred training provider to build their pilot pipelines Private, Instrument, Commercial Multi Also available with... & Certified Flight Instructor (Single, Multi 100 Hours Multi-Engine Experience with the best training in the fastest & Instrument) time frame possible. 225 Hours Flight Time / 100 Multi 230 Hours Flight Time / 40 Multi In the Airline Career Pilot Program, your airline Gain Access to More Corporate, Guaranteed Flight Instructor Job Charter, & Multi-Engine Instructor interview takes place during the commercial phase Job Opportunities of training. Successful applicants will receive a Airline conditional offer of employment at commercial phase of training, based on building Fly Farther & Faster with Multi- conditional offer of employment from one or more of flight experience to 1500 hours in your guaranteed Engine Crew Cross-Country ATP’s airline alliances, plus a guaranteed instructor CFI job. See website for participating airlines, Experience job with ATP or a designated flight school to build admissions, eligibility, and performance requirements. -

Infant and Toddler Contracted Slots Pilot Program: Evaluation Report Chad Dorn, Phd

Infant and Toddler Contracted Slots Pilot Program: Evaluation Report Chad Dorn, PhD. August 2020 2 Propulscreating force leading toon movement Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENT............................................................................................................... 4 OVERVIEW OF INFANT TODDLER CONTRACTED SLOTS PILOT ....................................... 5 THE EVALUATION........................................................................................................................ 7 Implementation Science (IS) Framework............................................................................... 7 Building the capacity to effectively implement...................................................................... 9 Implementation Teams............................................................................................... 9 Data-Informed Feedback Loops................................................................................. 9 Implementation Infrastructure.................................................................................. 10 Data Collection and Timeline................................................................................. ............... 10 Data Sources and Collection .................................................................................................. 11 Administrative Data.................................................................................................... 11 Program Director Survey – Pre and Post................................................................... -

Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture Through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses College of Arts & Sciences 5-2014 Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants. Alexandra O'Keefe University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/honors Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation O'Keefe, Alexandra, "Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants." (2014). College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses. Paper 62. http://doi.org/10.18297/honors/62 This Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. O’Keefe 1 Reflective Tales: Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants By Alexandra O’Keefe Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Graduation summa cum laude University of Louisville March, 2014 O’Keefe 2 The ability to adapt to the culture they occupy as well as the two-dimensionality of literary fairy tales allows them to relate to readers on a more meaningful level. -

Jekyll and Hyde Plot, Themes, Context and Key Vocabulary Booklet

Jekyll and Hyde Plot, Themes, Context and key vocabulary booklet Name: 1 2 Plot Mr Utterson and his cousin Mr Enfield are out for a walk when they pass a strange-looking door Chapter 1 - (which we later learn is the entrance to Dr Jekyll's laboratory). Enfield recalls a story involving the Story of the door. In the early hours of one winter morning, he says, he saw a man trampling on a young girl. He Door chased the man and brought him back to the scene of the crime. (The reader later learns that the man is Mr Hyde.) A crowd gathered and, to avoid a scene, the man offered to pay the girl compensation. This was accepted, and he opened the door with a key and re-emerged with a large cheque. Utterson is very interested in the case and asks whether Enfield is certain Hyde used a key to open the door. Enfield is sure he did. That evening the lawyer, Utterson, is troubled by what he has heard. He takes the will of his friend Dr Chapter 2 - Jekyll from his safe. It contains a worrying instruction: in the event of Dr Jekyll's disappearance, all his Search for possessions are to go to a Mr Hyde. Mr Hyde Utterson decides to visit Dr Lanyon, an old friend of his and Dr Jekyll's. Lanyon has never heard of Hyde, and not seen Jekyll for ten years. That night Utterson has terrible nightmares. He starts watching the door (which belongs to Dr Jekyll's old laboratory) at all hours, and eventually sees Hyde unlocking it. -

The Relative Cost-Effectiveness of Retaining Versus Accessing Air Force Pilots

The Relative Cost-Effectiveness of Retaining Versus Accessing Air Force Pilots Michael G. Mattock, Beth J. Asch, James Hosek, Michael Boito C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR2415 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0204-2 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2019 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: Getty Images/Fanatic Studio. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface The research discussed in this report was conducted for a project to develop an analytic capability for determining the efficient amount of special and incentive (S&I) pays for rated officers in the U.S. -

OJ Episode 1, FINAL, 6-3-15.Fdx Script

EPISODE 1: “FROM THE ASHES OF TRAGEDY” Written by Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski Based on “THE RUN OF HIS LIFE” By Jeffrey Toobin Directed by Ryan Murphy Fox 21 FX Productions Color Force FINAL 6-3-15 Ryan Murphy Television ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. COPYRIGHT © 2015 TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX FILM CORPORATION. NO PORTION OF THIS SCRIPT MAY BE PERFORMED, PUBLISHED, REPRODUCED, SOLD, OR DISTRIBUTED BY ANY MEANS OR QUOTED OR PUBLISHED IN ANY MEDIUM, INCLUDING ANY WEB SITE, WITHOUT PRIOR WRITTEN CONSENT OF TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX FILM CORPORATION. DISPOSAL OF THIS SCRIPT COPY DOES NOT ALTER ANY OF THE RESTRICTIONS SET FORTH ABOVE. 1 ARCHIVE FOOTAGE - THE RODNEY KING BEATING. Grainy, late-night 1 video. An AFRICAN-AMERICAN MAN lies on the ground. A handful of white LAPD COPS stand around, watching, while two of them ruthlessly BEAT and ATTACK him. ARCHIVE FOOTAGE - THE L.A. RIOTS. The volatile eruption of a city. Furious AFRICAN-AMERICANS tear Los Angeles apart. Trash cans get hurled through windows. Buildings burn. Cars get overturned. People run through the streets. Faces are angry, frustrated, screaming. The NOISE and FURY and IMAGES build, until -- SILENCE. Then, a single CARD: "TWO YEARS LATER" CUT TO: 2 EXT. ROCKINGHAM HOUSE - LATE NIGHT 2 ANGLE on a BRONZE STATUE of OJ SIMPSON, heroic in football regalia. Larger than life, inspiring. It watches over OJ'S estate, an impressive Tudor mansion on a huge corner lot. It's June 12, 1994. Out front, a young LIMO DRIVER waits. He nervously checks his watch. Then, OJ SIMPSON comes rushing from the house. -

Chapter 3-Deicing /Anti-Icing Fluids

When in Doubt... Small and Large Aircraft Aircraft Critical Surface Contamination Training For Aircrew and Groundcrew Seventh Edition December 2004 2 When in Doubt…TP 10643E How to Use This Manual This manual has been organized and written in chapter and summary format. Each chapter deals with certain topics that are reviewed in a summary at the end of the chapter. The manual is divided into two parts: Part 1-for aircrew and groundcrew; Part 2-additional information for ground crew. The final chapter contains questions that any operator may utilize for their ground icing program examination. The references for each question are listed to assist with answers. The Holdover Tables (HOT) included in the appendix are solely for the use with the examination questions and must not be used for operations. Contact Transport Canada from the addresses located later in this document for the latest HOT. Warnings These are used throughout this manual and are items, which will result in: damage to equipment, personal injury and/or loss of life if not carefully followed. Cautions These are used throughout this manual and are items, which may result in: damage to equipment, personal injury or loss of life if not carefully followed. Notes These are items that are intended to further explain details and clarify by amplifying important information. Should Implies that it is advisable to follow the suggested activity, process or practice. Must Implies that the suggested activity, process or practice needs to be followed because there are significant safety -

A Business Lawyer's Bibliography: Books Every Dealmaker Should Read

585 A Business Lawyer’s Bibliography: Books Every Dealmaker Should Read Robert C. Illig Introduction There exists today in America’s libraries and bookstores a superb if underappreciated resource for those interested in teaching or learning about business law. Academic historians and contemporary financial journalists have amassed a huge and varied collection of books that tell the story of how, why and for whom our modern business world operates. For those not currently on the front line of legal practice, these books offer a quick and meaningful way in. They help the reader obtain something not included in the typical three-year tour of the law school classroom—a sense of the context of our practice. Although the typical law school curriculum places an appropriately heavy emphasis on theory and doctrine, the importance of a solid grounding in context should not be underestimated. The best business lawyers provide not only legal analysis and deal execution. We offer wisdom and counsel. When we cast ourselves in the role of technocrats, as Ronald Gilson would have us do, we allow our advice to be defined downward and ultimately commoditized.1 Yet the best of us strive to be much more than legal engineers, and our advice much more than a mere commodity. When we master context, we rise to the level of counselors—purveyors of judgment, caution and insight. The question, then, for young attorneys or those who lack experience in a particular field is how best to attain the prudence and judgment that are the promise of our profession. For some, insight is gained through youthful immersion in a family business or other enterprise or experience. -

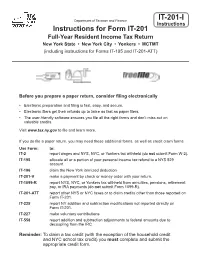

Instructions for Form IT-201 Full-Year Resident Income Tax Return

Department of Taxation and Finance IT-201-I Instructions Instructions for Form IT-201 Full-Year Resident Income Tax Return New York State • New York City • Yonkers • MCTMT (including instructions for Forms IT-195 and IT-201-ATT) Before you prepare a paper return, consider filing electronically • Electronic preparation and filing is fast, easy, and secure. • Electronic filers get their refunds up to twice as fast as paper filers. • The user-friendly software ensures you file all the right forms and don’t miss out on valuable credits. Visit www.tax.ny.gov to file and learn more. If you do file a paper return, you may need these additional forms, as well as credit claim forms. Use Form: to: IT-2 report wages and NYS, NYC, or Yonkers tax withheld (do not submit Form W-2). IT-195 allocate all or a portion of your personal income tax refund to a NYS 529 account. IT-196 claim the New York itemized deduction IT-201-V make a payment by check or money order with your return. IT-1099-R report NYS, NYC, or Yonkers tax withheld from annuities, pensions, retirement pay, or IRA payments (do not submit Form 1099-R). IT-201-ATT report other NYS or NYC taxes or to claim credits other than those reported on Form IT-201. IT-225 report NY addition and subtraction modifications not reported directly on Form IT-201. IT-227 make voluntary contributions IT-558 report addition and subtraction adjustments to federal amounts due to decoupling from the IRC. Reminder: To claim a tax credit (with the exception of the household credit and NYC school tax credit) you must complete and submit the appropriate credit form.