Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Managing Meritocracy in Clientelistic Democracies∗

Managing Meritocracy in Clientelistic Democracies∗ Sarah Brierleyy Washington University in St Louis May 8, 2018 Abstract Competitive recruitment for certain public-sector positions can co-exist with partisan hiring for others. Menial positions are valuable for sustaining party machines. Manipulating profes- sional positions, on the other hand, can undermine the functioning of the state. Accordingly, politicians will interfere in hiring partisans to menial position but select professional bureau- crats on meritocratic criteria. I test my argument using novel bureaucrat-level data from Ghana (N=18,778) and leverage an exogenous change in the governing party to investigate hiring pat- terns. The results suggest that partisan bias is confined to menial jobs. The findings shed light on the mixed findings regarding the effect of electoral competition on patronage; competition may dissuade politicians from interfering in hiring to top-rank positions while encouraging them to recruit partisans to lower-ranked positions [123 words]. ∗I thank Brian Crisp, Stefano Fiorin, Barbara Geddes, Mai Hassan, George Ofosu, Dan Posner, Margit Tavits, Mike Thies and Daniel Triesman, as well as participants at the African Studies Association Annual Conference (2017) for their comments. I also thank Gangyi Sun for excellent research assistance. yAssistant Professor, Department of Political Science, Washington University in St. Louis. Email: [email protected]. 1 Whether civil servants are hired by merit or on partisan criteria has broad implications for state capacity and the overall health of democracy (O’Dwyer, 2006; Grzymala-Busse, 2007; Geddes, 1994). When politicians exchange jobs with partisans, then these jobs may not be essential to the running of the state. -

Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: a Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation Amy J

American University International Law Review Volume 10 | Issue 4 Article 6 1995 Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: A Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation Amy J. Weisman Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Weisman, Amy J. "Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: A Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation." American University International Law Review 10, no. 4 (1995): 1365-1398. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SEPARATION OF POWERS IN POST- COMMUNIST GOVERNMENT: A CONSTITUTIONAL CASE STUDY OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION Amy J. Weisman* INTRODUCTION This comment explores the myriad of issues related to constructing and maintaining a stable, democratic, and constitutionally based govern- ment in the newly independent Russian Federation. Russia recently adopted a constitution that expresses a dedication to the separation of powers doctrine.' Although this constitution represents a significant step forward in the transition from command economy and one-party rule to market economy and democratic rule, serious violations of the accepted separation of powers doctrine exist. A thorough evaluation of these violations, and indeed, the entire governmental structure of the Russian Federation is necessary to assess its chances for a successful and peace- ful transition and to suggest alternative means for achieving this goal. -

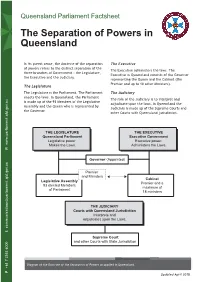

The Separation of Powers in Queensland

Queensland Parliament Factsheet The Separation of Powers in Queensland In its purest sense, the doctrine of the separation The Executive of powers refers to the distinct separation of the The Executive administers the laws. The three branches of Government - the Legislature, Executive in Queensland consists of the Governor the Executive and the Judiciary. representing the Queen and the Cabinet (the Premier and up to 18 other Ministers). The Legislature The Legislature is the Parliament. The Parliament The Judiciary enacts the laws. In Queensland, the Parliament The role of the Judiciary is to interpret and is made up of the 93 Members of the Legislative adjudicate upon the laws. In Queensland the Assembly and the Queen who is represented by Judiciary is made up of the Supreme Courts and the Governor. other Courts with Queensland jurisdiction. T ST T T Queensland Parliaent eutie oernent eislatie er ecutie er www.parliament.qld.gov.au aes the as dministers the as W Goernor inted Premier and inisters Cainet Leislatie ssel Premier and a elected emers maimum Parliament ministers T ourts with Queensland urisdition nterrets and adudicates un the as E [email protected] E [email protected] Supree ourt and ther urts ith tate urisdictin Diagram of the Doctrine of the Separation of Powers as applied in Queensland. +61 7 3553 6000 P Updated April 2018 Queensland Parliament Factsheet The Separation of Powers in Queensland Theoretically, each branch of government must be separate and not encroach upon the functions of the other branches. Furthermore, the persons who comprise these three branches must be kept separate and distinct. -

TESTING the SCHOLARS How Do You Choose Who Runs a Dynasty? Why Do People Seek Power?

TESTING THE SCHOLARS How do you choose who runs a dynasty? Why do people seek power? ACTIVITY DESCRIPTION Students will explore the classical Chinese civil servants exam system, compare it to / EDUCATOR their current exam systems, and construct their own ideas of what it means to be qualified for a role and how to prove qualification. If you are planning to use this as part of a visit to The Field Museum, see the Page field trip guide on page 7. 1 of BACKGROUND 7 INFORMATION Image: During the Qing Dynasty, students took the civil service examination in door-less cells. Running an empire required a network of The only furniture was a set of boards that could be arranged as a desk and bench or a bed. dedicated and well-educated officials. The men Illustration by Sayaka Isowa for The Field Museum. who governed the empire had to pass a grueling exam. For roughly 1,300 years, China’s emperors used the civil toe, twice. Their supplies, carried in baskets like service examination system to identify talented men for the ones in the drawing above, were searched. It’s government service. Stationed throughout the empire, said that guards even checked inside dumplings. scholar-officials maintained order and reported back to Yet some test-takers found ways to smuggle in help. the emperor on local events. This system was so effective, The museum holds examples of silk cloth covered in even foreign dynasties like the Manchus embraced it writing, cheat sheets that could have been sewn into during the Qing Dynasty (AD 1644-1911). -

Separation of Powers and the Independence of Constitutional Courts and Equivalent Bodies

1 Christoph Grabenwarter Separation of Powers and the Independence of Constitutional Courts and Equivalent Bodies Keynote Speech 16 January 2011 2nd Congress of the World Conference on Constitutional Justice, Rio de Janeiro 1. Introduction Separation of Power is one of the basic structural principles of democratic societies. It was already discussed by ancient philosophers, deep analysis can be found in medieval political and philosophical scientific work, and we base our contemporary discussion on legal theory that has been developed in parallel to the emergence of democratic systems in Northern America and in Europe in the 18 th Century. Separation of Powers is not an end in itself, nor is it a simple tool for legal theorists or political scientists. It is a basic principle in every democratic society that serves other purposes such as freedom, legality of state acts – and independence of certain organs which exercise power delegated to them by a specific constitutional rule. When the organisers of this World Conference combine the concept of the separation of powers with the independence of constitutional courts, they address two different aspects. The first aspect has just been mentioned. The independence of constitutional courts is an objective of the separation of powers, independence is its result. This is the first aspect, and perhaps the aspect which first occurs to most of us. The second aspect deals with the reverse relationship: independence of constitutional courts as a precondition for the separation of powers. Independence enables constitutional courts to effectively control the respect for the separation of powers. As a keynote speech is not intended to provide a general report on the results of the national reports, I would like to take this opportunity to discuss certain questions raised in the national reports and to add some thoughts that are not covered by the questionnaire sent out a few months ago, but are still thoughts on the relationship between the constitutional principle and the independence of constitutional judges. -

Separation of Powers Between County Executive and County Fiscal Body

Separation of Powers Between County Executive and County Fiscal Body Karen Arland Ice Miller LLP September 27, 2017 Ice on Fire Separation of Powers Division of governmental authority into three branches – legislative, executive and judicial, each with specified duties on which neither of the other branches can encroach A constitutional doctrine of checks and balances designed to protect the people against tyranny 1 Ice on Fire Historical Background The phrase “separation of powers” is traditionally ascribed to French Enlightenment political philosopher Montesquieu, in The Spirit of the Laws, in 1748. Also known as “Montesquieu’s tri-partite system,” the theory was the division of political power between the executive, the legislature, and the judiciary as the best method to promote liberty. 2 Ice on Fire Constitution of the United States Article I – Legislative Section 1 – All legislative Powers granted herein shall be vested in a Congress of the United States. Article II – Executive Section 1 – The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America. Article III – Judicial The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish. 3 Ice on Fire Indiana Constitution of 1816 Article II - The powers of the Government of Indiana shall be divided into three distinct departments, and each of them be confided to a separate body of Magistracy, to wit: those which are Legislative to one, those which are Executive to another, and those which are Judiciary to another: And no person or collection of persons, being of one of those departments, shall exercise any power properly attached to either of the others, except in the instances herein expressly permitted. -

Meritocracy: a Widespread Ideology Due to School Socialization? Marie Duru-Bellat, Elise Tenret

Meritocracy: A widespread ideology due to school socialization? Marie Duru-Bellat, Elise Tenret To cite this version: Marie Duru-Bellat, Elise Tenret. Meritocracy: A widespread ideology due to school socialization?. 2010. hal-00972712 HAL Id: hal-00972712 https://hal-sciencespo.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00972712 Preprint submitted on 3 Apr 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Meritocracy: A Widespread Ideology Due to School Socialization? Marie Duru-Bellat et Elise Tenret Notes & Documents n° 2010-02 Juillet 2010 Résumé : La recherche présentée dans ce papier se centre sur la perception de la méritocratie et sur l’adhésion à la méritocratie scolaire. En la matière, on explore précisément l’influence de l’éducation à la fois au niveau micro (individuel) et au niveau macro (pays), dans la mesure où l’éducation, selon Bourdieu et Passeron (1970) est censée affecter l’adhésion aux idéologies dominantes. Cependant, ces chercheurs n’en apportent pas de preuve empirique. De plus, l’influence de l’éducation n’est pas univoque, car elle peut avoir des effets contradictoires sur la justification des inégalités sociales (Baer et Lambert 1982), et aussi parce que ces effets peuvent être différents selon le niveau d’analyse (individus ou pays). -

The Man Behind the Cloud an Interview with Vmware’S Paul Maritz

fear, greed and fairy tales • p.j. o’rourke is out off wworkrk It Pays to Be Lucky Where Have the Leaders Gone? Formula One’s Benign Despot The Buck Starts Here The Man Behind the Cloud An Interview with VMware’s Paul Maritz Q1.2012.2012 chief executive officer Gary Burnison chief marketing officer Michael Distefano editor-in-chief Joel Kurtzman creative director Joannah Ralston circulation director Peter Pearsall marketing operations manager Reonna Johnson board of advisors Sergio Averbach Cheryl Buxton Joe Griesedieck Byrne Mulrooney Kristen Badgley Dennis Carey Robert Hallagan Indranil Roy Michael Bekins Bob Damon Katie Lahey Jane Stevenson Stephen Bruyant-Langer Ana Dutra Robert McNabb Anthony Vardy contributing editors Chris Bergonzi Stephanie Mitchell David Berreby P.J. O’Rourke Lawrence M. Fisher Glenn Rifkin Victoria Griffi th Adrian Wooldridge Cover photo of Paul Maritz: The Korn/Ferry International Briefi ngs on Talent and Leadership is published Jeff Singer quarterly by the Korn/Ferry Institute. The Korn/Ferry Institute was founded to serve Cover illustration: as a premier global voice on a range of talent management and leadership issues. The Zé Otavio Institute commissions, originates and publishes groundbreaking research utilizing Korn/ Ferry’s unparalleled expertise in executive recruitment and talent development combined with its preeminent behavioral research library. The Institute is dedicated to improving the state of global human capital for businesses of all sizes around the world. ISSN 1949-8365 Copyright 2012, Korn/Ferry International Requests for additional copies should be sent directly to: Briefi ngs Magazine 1900 Avenue of the Stars, Suite 2600, Los Angeles, CA 90067 briefi [email protected] Briefi ngs is produced with solar power, FSC-certifi ed Advertising Sales Representative: paper, and soy-based inks, Erica Springer + Associates, LLC in a fully sustainable and 1355 S. -

Between Political Meritocracy and Participatory Democracy: Toward Realist Confucian Democracy

Culture and Dialogue 8 (2020) 251-279 brill.com/cad Between Political Meritocracy and Participatory Democracy: Toward Realist Confucian Democracy Darren Yutang Jin Hertford College, Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK [email protected] Abstract In this article, I examine the textual underpinnings of participatory Confucian democ- racy and Confucian meritocracy and propose realist Confucian democracy as an alter- native following a balanced reading of classic Confucianism. I argue that Confucian plebeian values do not square with the political meritocrats’ (Daniel A. Bell and Tongdong Bai) advocacy for meritocratic rule while Confucian elitist values undermine participatory democrats’ (Sor-hoon Tan and Stephen Angle) ardor for justifications of active democratic participation. A shared difficulty with both groups is that they tend to overuse one aspect of Confucianism while leaving the status of other elements in limbo. The discussion of participatory democracy and meritocracy is followed by the introduction of an eclectic reading that strikes a dynamic balance between elitist and plebeian values in Confucianism, and which points to the wide gamut of realist de- mocracy that combines democratic election with strong leadership. Keywords participatory Confucian democracy – Confucian meritocracy – realist Confucian democracy – classic Confucianism – Confucian political theory – political realism 1 Introduction Recent focus on the relationship between Confucianism and democracy has shifted away from examining their mere compatibility to discussing possibilities © Darren Yutang Jin, 2020 | doi:10.1163/24683949-12340086 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY 4.0Downloaded license. from Brill.com09/27/2021 01:35:19AM via free access 252 Jin of “Confucian democracy” and “Confucian meritocracy” that build on the intellectual strength of both traditions. -

Meritocratic Elitism, Authoritarian Libertarianism, and the Limits of the China Model Or: What Are We Talking About When We Talk About Alternatives?

SYMPOSIUM THE CHINA MODEL MERITOCRATIC ELITISM, AUTHORITARIAN LIBERTARIANISM, AND THE LIMITS OF THE CHINA MODEL OR: WHAT ARE WE TALKING ABOUT WHEN WE TALK ABOUT ALTERNATIVES? BY PEITAO JIA © 2017 ² Philosophy and Public Issues (New Series), Vol. 7, No. 1 (2017): 105-126 Luiss University Press E-ISSN 2240-7987 | P-ISSN 1591-0660 [THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK] THE CHINA MODEL Meritocratic Elitism, Authoritarian Libertarianism, and the Limits of The China Model Or: What are We Talking about When We Talk about Alternatives? Peitao Jia n this article, as a review and critique of the current theorization and defense of political meritocracy (PM), I I examine what the factual political issues demand and what the theory of PM has promised and provided. By arguing that PM leads to meritocratic elitism that neglects individual citizens· civil and political rights as well as authoritarian libertarianism that undermines the people·s economic, social, and cultural welfare, I shall conclude this discussion with remarks that political meritocracy cannot be a desirable alternative to liberal democracy and on the contrary it requires its own alternatives based on liberal and egalitarian values. As one of the most important contemporary theorists of political meritocracy, Daniel A. Bell defends this selection-and- promotion system as an ´alternative modelµ to liberal democracy (LD) in his well-argued book The China Model: Political Meritocracy and the Limits of Democracy.1 1 Daniel A. Bell, The China Model: Political Meritocracy and the Limits of Democracy (Princeton: Princeton University Press 2015), p. 4. © 2017 ² Philosophy and Public Issues (New Series), Vol. -

The 03Rd Century This Is the Century of the Military Showdown

86 3. The State The 03rd Century This is the century of the military showdown. In the east, Ch! M"!n-wa!ng, who ruled from 0300, was eager for conquest. After long delay for preparation, a delay which the Gwa"ndz" theorists urgently advised, he attacked Su# ng in 0285. And conquered it, but allied states drove him from Su# ng and from Ch! itself. He died far from his capital in 0284, and Ch! never again ranked as a major power. Its eclipse favored its western rival: Ch!n. Lord Sha$ng or We#! Ya$ng, a general of Ch!n, had defeated Ngwe#! in 0342; he was given the fief of Sha$ng and a ministership in 0341. His reputation in other states was military, but Ch!n tradition (found in the Sha$ng-jyw$nShu$) claimed him as a statesman, and it is possible that he applied military discipline (harsh punishments, no exemptions for nobles) to the civilian population also. As in Ch!, reward and punishment are the root axioms of 03c Ch!n legal theory: 3:72 (SJS 9:2a, excerpt, c0295). Now, the nature of men is to like titles and salaries and to hate punishments and penalties. A ruler institutes these two things to control men’s wills . But in contrast to eastern thought, the SJS firmly rejects antiquity arguments: 3:73 (SJS 7:2c, excerpt, c0288). The Sage neither imitates the ancient nor cultivatesthemodern...theThreeDynastieshaddifferentsituations,but they all managed to rule. Thus, to rise to the Kingship, there is one way, but to hold it, there are different principles. -

The Separation of Powers Doctrine: an Overview of Its Rationale and Application

Order Code RL30249 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web The Separation of Powers Doctrine: An Overview of its Rationale and Application June 23, 1999 (name redacted) Legislative Attorney American Law Division Congressional Research Service The Library of Congress ABSTRACT This report discusses the philosophical underpinnings, constitutional provisions, and judicial application of the separation of powers doctrine. In the United States, the doctrine has evolved to entail the identification and division of three distinct governmental functions, which are to be exercised by separate branches of government, classified as legislative, executive, and judicial. The goal of this separation is to promote governmental efficiency and prevent the excessive accumulation of power by any single branch. This has been accomplished through a hybrid doctrine comprised of the separation of powers principle and the notion of checks and balances. This structure results in a governmental system which is independent in certain respects and interdependent in others. The Separation of Powers Doctrine: An Overview of its Rationale and Application Summary As delineated in the Constitution, the separation of powers doctrine represents the belief that government consists of three basic and distinct functions, each of which must be exercised by a different branch of government, so as to avoid the arbitrary exercise of power by any single ruling body. This concept was directly espoused in the writings of Montesquieu, who declared that “when the executive