The Separation-Of-Powers Theory of Standing, 95 N.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requir

Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Economics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Gérard Roland, Chair Professor Ernesto Dal Bó Associate Professor Fred Finan Associate Professor Yuriy Gorodnichenko Spring 2018 Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences Copyright 2018 by Weijia Li 1 Abstract Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li Doctor of Philosophy in Economics University of California, Berkeley Professor Gérard Roland, Chair This dissertation explores how to solve incentive problems in autocracies through institu- tional arrangements centered around political meritocracy. The question is fundamental, as merit-based rewards and promotion of politicians are the cornerstones of key authoritarian regimes such as China. Yet the grave dilemmas in bureaucratic governance are also well recognized. The three essays of the dissertation elaborate on the various solutions to these dilemmas, as well as problems associated with these solutions. Methodologically, the disser- tation utilizes a combination of economic modeling, original data collection, and empirical analysis. The first chapter investigates the puzzle why entrepreneurs invest actively in many autoc- racies where unconstrained politicians may heavily expropriate the entrepreneurs. With a game-theoretical model, I investigate how to constrain politicians through rotation of local politicians and meritocratic evaluation of politicians based on economic growth. The key finding is that, although rotation or merit-based evaluation alone actually makes the holdup problem even worse, it is exactly their combination that can form a credible constraint on politicians to solve the hold-up problem and thus encourages private investment. -

Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: a Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation Amy J

American University International Law Review Volume 10 | Issue 4 Article 6 1995 Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: A Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation Amy J. Weisman Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Weisman, Amy J. "Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: A Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation." American University International Law Review 10, no. 4 (1995): 1365-1398. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SEPARATION OF POWERS IN POST- COMMUNIST GOVERNMENT: A CONSTITUTIONAL CASE STUDY OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION Amy J. Weisman* INTRODUCTION This comment explores the myriad of issues related to constructing and maintaining a stable, democratic, and constitutionally based govern- ment in the newly independent Russian Federation. Russia recently adopted a constitution that expresses a dedication to the separation of powers doctrine.' Although this constitution represents a significant step forward in the transition from command economy and one-party rule to market economy and democratic rule, serious violations of the accepted separation of powers doctrine exist. A thorough evaluation of these violations, and indeed, the entire governmental structure of the Russian Federation is necessary to assess its chances for a successful and peace- ful transition and to suggest alternative means for achieving this goal. -

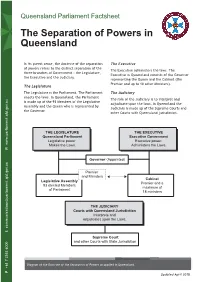

The Separation of Powers in Queensland

Queensland Parliament Factsheet The Separation of Powers in Queensland In its purest sense, the doctrine of the separation The Executive of powers refers to the distinct separation of the The Executive administers the laws. The three branches of Government - the Legislature, Executive in Queensland consists of the Governor the Executive and the Judiciary. representing the Queen and the Cabinet (the Premier and up to 18 other Ministers). The Legislature The Legislature is the Parliament. The Parliament The Judiciary enacts the laws. In Queensland, the Parliament The role of the Judiciary is to interpret and is made up of the 93 Members of the Legislative adjudicate upon the laws. In Queensland the Assembly and the Queen who is represented by Judiciary is made up of the Supreme Courts and the Governor. other Courts with Queensland jurisdiction. T ST T T Queensland Parliaent eutie oernent eislatie er ecutie er www.parliament.qld.gov.au aes the as dministers the as W Goernor inted Premier and inisters Cainet Leislatie ssel Premier and a elected emers maimum Parliament ministers T ourts with Queensland urisdition nterrets and adudicates un the as E [email protected] E [email protected] Supree ourt and ther urts ith tate urisdictin Diagram of the Doctrine of the Separation of Powers as applied in Queensland. +61 7 3553 6000 P Updated April 2018 Queensland Parliament Factsheet The Separation of Powers in Queensland Theoretically, each branch of government must be separate and not encroach upon the functions of the other branches. Furthermore, the persons who comprise these three branches must be kept separate and distinct. -

Separation of Powers and the Independence of Constitutional Courts and Equivalent Bodies

1 Christoph Grabenwarter Separation of Powers and the Independence of Constitutional Courts and Equivalent Bodies Keynote Speech 16 January 2011 2nd Congress of the World Conference on Constitutional Justice, Rio de Janeiro 1. Introduction Separation of Power is one of the basic structural principles of democratic societies. It was already discussed by ancient philosophers, deep analysis can be found in medieval political and philosophical scientific work, and we base our contemporary discussion on legal theory that has been developed in parallel to the emergence of democratic systems in Northern America and in Europe in the 18 th Century. Separation of Powers is not an end in itself, nor is it a simple tool for legal theorists or political scientists. It is a basic principle in every democratic society that serves other purposes such as freedom, legality of state acts – and independence of certain organs which exercise power delegated to them by a specific constitutional rule. When the organisers of this World Conference combine the concept of the separation of powers with the independence of constitutional courts, they address two different aspects. The first aspect has just been mentioned. The independence of constitutional courts is an objective of the separation of powers, independence is its result. This is the first aspect, and perhaps the aspect which first occurs to most of us. The second aspect deals with the reverse relationship: independence of constitutional courts as a precondition for the separation of powers. Independence enables constitutional courts to effectively control the respect for the separation of powers. As a keynote speech is not intended to provide a general report on the results of the national reports, I would like to take this opportunity to discuss certain questions raised in the national reports and to add some thoughts that are not covered by the questionnaire sent out a few months ago, but are still thoughts on the relationship between the constitutional principle and the independence of constitutional judges. -

Separation of Powers Between County Executive and County Fiscal Body

Separation of Powers Between County Executive and County Fiscal Body Karen Arland Ice Miller LLP September 27, 2017 Ice on Fire Separation of Powers Division of governmental authority into three branches – legislative, executive and judicial, each with specified duties on which neither of the other branches can encroach A constitutional doctrine of checks and balances designed to protect the people against tyranny 1 Ice on Fire Historical Background The phrase “separation of powers” is traditionally ascribed to French Enlightenment political philosopher Montesquieu, in The Spirit of the Laws, in 1748. Also known as “Montesquieu’s tri-partite system,” the theory was the division of political power between the executive, the legislature, and the judiciary as the best method to promote liberty. 2 Ice on Fire Constitution of the United States Article I – Legislative Section 1 – All legislative Powers granted herein shall be vested in a Congress of the United States. Article II – Executive Section 1 – The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America. Article III – Judicial The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish. 3 Ice on Fire Indiana Constitution of 1816 Article II - The powers of the Government of Indiana shall be divided into three distinct departments, and each of them be confided to a separate body of Magistracy, to wit: those which are Legislative to one, those which are Executive to another, and those which are Judiciary to another: And no person or collection of persons, being of one of those departments, shall exercise any power properly attached to either of the others, except in the instances herein expressly permitted. -

The Separation of Powers Doctrine: an Overview of Its Rationale and Application

Order Code RL30249 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web The Separation of Powers Doctrine: An Overview of its Rationale and Application June 23, 1999 (name redacted) Legislative Attorney American Law Division Congressional Research Service The Library of Congress ABSTRACT This report discusses the philosophical underpinnings, constitutional provisions, and judicial application of the separation of powers doctrine. In the United States, the doctrine has evolved to entail the identification and division of three distinct governmental functions, which are to be exercised by separate branches of government, classified as legislative, executive, and judicial. The goal of this separation is to promote governmental efficiency and prevent the excessive accumulation of power by any single branch. This has been accomplished through a hybrid doctrine comprised of the separation of powers principle and the notion of checks and balances. This structure results in a governmental system which is independent in certain respects and interdependent in others. The Separation of Powers Doctrine: An Overview of its Rationale and Application Summary As delineated in the Constitution, the separation of powers doctrine represents the belief that government consists of three basic and distinct functions, each of which must be exercised by a different branch of government, so as to avoid the arbitrary exercise of power by any single ruling body. This concept was directly espoused in the writings of Montesquieu, who declared that “when the executive -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. 19-7 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States SEILA LAW LLC, Petitioner, v. CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU, Respondent. On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE SOUTHEASTERN LEGAL FOUNDATION AND NATIONAL FEDERATION OF INDEPENDENT BUSINESS SMALL BUSINESS LEGAL CENTER IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER Kimberly S. Hermann Scott A. Keller SOUTHEASTERN LEGAL Counsel of Record FOUNDATION Noah R. Mink 560 W. Crossville Rd., Ste. 104 BAKER BOTTS L.L.P. Roswell, GA 30075 1299 Pennsylvania Ave. NW Washington, DC 20004 Karen R. Harned (202) 639-7700 Luke A. Wake [email protected] NFIB SMALL BUSINESS LEGAL CENTER 1201 F St., NW, Ste. 200 Washington, DC 20004 Counsel for Amici Curiae WILSON-EPES PRINTING CO., INC. – (202) 789-0096 – WASHINGTON, D.C. 20002 TABLE OF CONTENTS Interest of Amici Curiae .................................................... 1 Summary of Argument ........................................................ 3 Argument .............................................................................. 5 I. The Separation of Powers Acts as an Essential Safeguard of Individual Liberty ............................. 5 II. The CFPB Undermines Individual Liberty, Because It Lacks Structural Features Present in Executive Agencies and Other Independent Agencies................................................................... 10 Conclusion ........................................................................... 17 (i) TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page(s) CASES Allen v. Wright, -

Federalism, Separation of Powers, and Individual Liberties

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 40 Issue 6 Issue 6 - November 1987 Article 5 11-1987 Federalism, Separation of Powers, and Individual Liberties Dennis G. LaGory Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Fourth Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Dennis G. LaGory, Federalism, Separation of Powers, and Individual Liberties, 40 Vanderbilt Law Review 1353 (1987) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol40/iss6/5 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Federalism, Separation of Powers, and Individual Liberties* I. INTRODUCTION: GOALS AND GOVERNMENT We the People of the United States, in Order to . .secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitu- tion for the United States of America.' The Framers began the Constitution with this statement of purpose because the philosophical tradition that spawned their po- litical temperament viewed the preservation of liberty as the chief objective of government.2 This tradition hypothesized that man, prior to the formation of organized society, lived in a state of per- fect freedom and equality.' In this state, all men possessed natural liberty. According to William Blackstone, one of the eighteenth century's most respected -

New York University Law Review

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\91-2\NYU201.txt unknown Seq: 1 11-MAY-16 12:26 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VOLUME 91 MAY 2016 NUMBER 2 ARTICLES OF CONSTITUTIONAL CUSTODIANS AND REGULATORY RIVALS: AN ACCOUNT OF THE OLD AND NEW SEPARATION OF POWERS JON D. MICHAELS* The theory and reality of “administrative separation of powers” requires revisions to the longstanding legal, normative, and positive accounts of bureaucratic control. Because these leading accounts are often insufficiently attentive to the fragmented nature of administrative power, they tend to overlook the fact that internal adminis- trative rivals—perhaps as much as Congress, the President, and the courts—shape agency behavior. In short, these accounts do not connect what we might call the old and new separation of powers. They thus fail to capture the multidimensional nature of administrative control in which the constitutional branches (the old sepa- ration of powers) and the administrative rivals (the new separation of powers) all compete with one another to influence administrative governance. This Article, the first to connect novel insights regarding administrative separation of powers to old—and seemingly settled—debates over the design and desirability of bureaucratic control, (1) characterizes the administrative sphere as a legitimate, largely self-regulating ecosystem, (2) recognizes the capacity of three rivals—politi- cally appointed agency heads, politically insulated civil servants, and members of * Copyright © 2016 by Jon D. Michaels, Professor of Law, UCLA School of Law. For helpful comments and conversations, thanks are owed to Bruce Ackerman, Eric Berger, Frederic Bloom, Josh Chafetz, Kristen Eichensehr, David Fontana, Aziz Huq, Harold Koh, Randy Kozel, Allison Orr Larsen, Toni Michaels, Anne Joseph O’Connell, David Pozen, Richard Re, David Rubenstein, Jennifer Selin, and David Super. -

Book Review Reconstructing the Administrative State in an Era of Economic and Democratic Crisis

BOOK REVIEW RECONSTRUCTING THE ADMINISTRATIVE STATE IN AN ERA OF ECONOMIC AND DEMOCRATIC CRISIS CONSTITUTIONAL COUP: PRIVATIZATION’S THREAT TO THE AMERICAN REPUBLIC. By Jon D. Michaels. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. 2017. Pp. 312. $35.00. Reviewed by K. Sabeel Rahman∗ Speaking at Yale Law School in 1938, Dean James Landis offered a powerful defense of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, and in particular its innovation of new federal administrative agencies. “The administrative process,” declared Landis, “is, in essence, our genera- tion’s answer to the inadequacy of the judicial and the legislative pro- cess.”1 Unlike generalist legislatures or formalist judges, administrative agencies could address the complexities of the modern economy and in- dustrial society by harnessing their expertise, professionalism, and inde- pendence to serve the public interest. Not everyone shared Landis’s celebration of this new era of American state building. The eminent Dean Roscoe Pound, then chair of an American Bar Association special committee evaluating the rise of the New Deal administrative state, saw the mixing of legislative, executive, and adjudicatory functions in agen- cies like the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) — which Landis himself designed and later chaired — as tantamount to “admin- istrative absolutism.”2 The debate between Landis and the New Dealers on the one hand, and the old guard of legal scholars like Pound on the other, is by now a familiar story in the origins of the modern administrative state.3 By the time of Pound’s report, the Supreme Court had already begun its recon- ciliation with Roosevelt’s New Deal following the 1937 “switch in ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– ∗ Assistant Professor of Law, Brooklyn Law School. -

Separation of Powers Doctrine As Applied to Cities

Indiana Law Journal Volume 18 Issue 2 Article 12 Winter 1943 Separation of Powers Doctrine As Applied to Cities Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Business Organizations Law Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation (1943) "Separation of Powers Doctrine As Applied to Cities," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 18 : Iss. 2 , Article 12. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol18/iss2/12 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INDIANA LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 18 MUNICIPAL CORPORATIONS SEPARATION OF POWERS DOCTRINE AS APPLIED TO CITIES The municipal Council of the city of New York under authority of the city charter investigated the Municipal Civil Service Commis- sion. It served a subpoena duces tecum upon the Mayor in an effort to secure the written report of a related investigation. The Mayor ap- plied for an order to vacate the Council's subpoena. Held, the rec- ords of the Mayor pertinent to the investigation-are not immune from the Council's power of subpoena.1 The principal issue was whether the doctrine of separation of governmental powers applied to municipal governments. The classical strictness2 of this doctrine has been modified in both federal3 and state4 application by modern decisions. However, the principle of executive immunity from process by either of the 1. -

Martin Powers in Conversation with Sandra Field, Jeffrey Flynn, Stephen Macedo, and Longxi Zhang∗ ______

Journal of World Philosophies Author Meets Readers/188 Authors Meets Readers: Martin Powers in Conversation with Sandra Field, ∗ Jeffrey Flynn, Stephen Macedo, and Longxi Zhang __________________________________________ China and England: On the Structural Convergence of Political Values, Responding to Martin Powers’ China and England: The Preindustrial Struggle for Social Justice in Word and Image1 SANDRA LEONIE FIELD Yale-NUS College, Singapore ([email protected]) 1 Overview At the center of Powers’ China and England (2019) is an extraordinary forgotten episode in the history of political ideas. There was a time when English radicals critiqued the corruption and injustice of the English political system by contrasting it with the superior example of China. There was a time when they advocated adopting a Chinese conceptual framework for thinking about politics. So dominant and prevalent was the English radicals’ use of this framework that their opponents took to dismissing their points as “the argument from the Chinese” (168, 190). The core historical evidence of this episode is a remarkable set of texts from or about China published in English from the late seventeenth century up to the mid-eighteenth century, and subsequent commentaries and adoptions of those texts. Most striking amongst the Chinese texts are accounts of Song dynasty politics and administration. Specifically, the Chinese example was used to bring certain key ideas to England as a model of politics for the English to emulate: • meritocracy, rather than rank and authority as hereditary or at the pleasure of the sovereign; • equality under the law, rather than legal procedures differentiated by group membership; • separation of public and private (both a conception of office and a conception of public good); and • an ideal of political rule guided by concern for the common people.