Separation of Powers and the Independence of Constitutional Courts and Equivalent Bodies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fundamentals of Constitutional Courts

Constitution Brief April 2017 Summary The Fundamentals of This Constitution Brief provides a basic guide to constitutional courts and the issues that they raise in constitution-building processes, and is Constitutional Courts intended for use by constitution-makers and other democratic actors and stakeholders in Myanmar. Andrew Harding About MyConstitution 1. What are constitutional courts? The MyConstitution project works towards a home-grown and well-informed constitutional A written constitution is generally intended to have specific and legally binding culture as an integral part of democratic transition effects on citizens’ rights and on political processes such as elections and legislative and sustainable peace in Myanmar. Based on procedure. This is not always true: in the People’s Republic of China, for example, demand, expert advisory services are provided it is clear that constitutional rights may not be enforced in courts of law and the to those involved in constitution-building efforts. constitution has only aspirational, not juridical, effects. This series of Constitution Briefs is produced as If a constitution is intended to be binding there must be some means of part of this effort. enforcing it by deciding when an act or decision is contrary to the constitution The MyConstitution project also provides and providing some remedy where this occurs. We call this process ‘constitutional opportunities for learning and dialogue on review’. Constitutions across the world have devised broadly two types of relevant constitutional issues based on the constitutional review, carried out either by a specialized constitutional court or history of Myanmar and comparative experience. by courts of general legal jurisdiction. -

Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requir

Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Economics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Gérard Roland, Chair Professor Ernesto Dal Bó Associate Professor Fred Finan Associate Professor Yuriy Gorodnichenko Spring 2018 Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences Copyright 2018 by Weijia Li 1 Abstract Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li Doctor of Philosophy in Economics University of California, Berkeley Professor Gérard Roland, Chair This dissertation explores how to solve incentive problems in autocracies through institu- tional arrangements centered around political meritocracy. The question is fundamental, as merit-based rewards and promotion of politicians are the cornerstones of key authoritarian regimes such as China. Yet the grave dilemmas in bureaucratic governance are also well recognized. The three essays of the dissertation elaborate on the various solutions to these dilemmas, as well as problems associated with these solutions. Methodologically, the disser- tation utilizes a combination of economic modeling, original data collection, and empirical analysis. The first chapter investigates the puzzle why entrepreneurs invest actively in many autoc- racies where unconstrained politicians may heavily expropriate the entrepreneurs. With a game-theoretical model, I investigate how to constrain politicians through rotation of local politicians and meritocratic evaluation of politicians based on economic growth. The key finding is that, although rotation or merit-based evaluation alone actually makes the holdup problem even worse, it is exactly their combination that can form a credible constraint on politicians to solve the hold-up problem and thus encourages private investment. -

ONE the SUPREME COURT and the MAKING of PUBLIC POLICY in CONTEMPORARY CHINA Eric C. Ip

ONE THE SUPREME COURT AND THE MAKING OF PUBLIC POLICY IN CONTEMPORARY CHINA Eric C. Ip Post-Mao China saw profound social, economic and legal changes. This paper analyzes an often neglected aspect of these transformations: the evolution of the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) into an increasingly influential political actor in national law and policy-making. The SPC has self-consciously redefined its mandate to manage state-sponsored legal reforms by performing an expansive range of new functions such as issuing abstract rules, tightening control over lower courts and crafting out a constitutional jurisprudence of its own at the expense of other powerful state actors. It is more assertive than ever its own vision of how law should develop in the contemporary People’s Republic of China (PRC)SPC action can be broadly consistent with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) interests, autonomous and expansive at the same time. However, the SPC’s reform initiatives are inevitably constrained by the vested interests of major bureaucratic players as well as the Party’s insistence on maintaining the Court as an integral administrative agency of its public security system. Eric C. Ip is working towards a doctorate at Oxford University's Centre for Socio- Legal Studies. A student of the political science subfields of comparative constitutional design and judicial politics, he earned his undergraduate degree in Government and Laws from The University of Hong Kong, and an LL.M. (distinction) degree from King's College, University of London. He is an Academic Tutor in Law and Politics at St. John's College, The University of Hong Kong; an Academic Fellow at The Institute of Law, Economics, and Politics; and a member of the American Political Science Association and the British Institute of International and Comparative Law. -

Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: a Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation Amy J

American University International Law Review Volume 10 | Issue 4 Article 6 1995 Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: A Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation Amy J. Weisman Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Weisman, Amy J. "Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: A Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation." American University International Law Review 10, no. 4 (1995): 1365-1398. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SEPARATION OF POWERS IN POST- COMMUNIST GOVERNMENT: A CONSTITUTIONAL CASE STUDY OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION Amy J. Weisman* INTRODUCTION This comment explores the myriad of issues related to constructing and maintaining a stable, democratic, and constitutionally based govern- ment in the newly independent Russian Federation. Russia recently adopted a constitution that expresses a dedication to the separation of powers doctrine.' Although this constitution represents a significant step forward in the transition from command economy and one-party rule to market economy and democratic rule, serious violations of the accepted separation of powers doctrine exist. A thorough evaluation of these violations, and indeed, the entire governmental structure of the Russian Federation is necessary to assess its chances for a successful and peace- ful transition and to suggest alternative means for achieving this goal. -

Elements of Sociology of the Supreme People's Court

Paper presented at the Conference ”Constitutionalism and Judicial Power in China” (December 12-13 2005, Sciences Po) HIGH TURNOVER AND LOW REPUTATION? ELEMENTS OF SOCIOLOGY OF THE SUPREME PEOPLE’S COURT GRAND JUSTICES (Summary) Hou Meng Department of Sociology, Beijing University This presentation about the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) Grand Justices of the PRC consists of two papers. The first one discusses the high turnover of Grand Justices and the underlying reasons, while the second focuses on the reputation of Grand Justices. Actually, high turnover and low reputation have intrinsic connections. Leaving the Supreme People’s Court: the Turnover of SPC Grand Justices In recent years, SPC has applied judge’s professionalization to all the Courts of China so as to ensure the stabilization of judge group. On the contrary, three Grand Justices have left SPC since 2003. The first one is Zhu Mingsha, the Grand Justice of the first rank and Vice President of SPC, who left for the Committee for Internal and Judicial Affairs of Standing Committee of the National People's Congress (SCNPC) and took the position as its Vice President. The second one is Zhang Jun, the Grand Justice of the second rank, from the Vice President of SPC to Vice Minister of Justice (he came back to SPC in Aug, 2005). The third one is Jiang Bixin, the Grand Justice of the second rank, from the Vice President of SPC to the President of the Higher People’s Court of Hunan Province. What leads to the above inconsistent phenomena? Continual Turnover Leaving the Court is one type of judge turnover. -

Why Governments Target Civil Society and What Can Be Done in Response a New Agenda

APRIL 2015 Why Governments Target Civil Society and What Can Be Done in Response A New Agenda AUTHOR Sarah E. Mendelson A Report of the CSIS Human Rights Initiative 1616 Rhode Island Avenue NW Washington, DC 20036 202-887-0200 | www.csis.org Cover photo: Shutterstock.com. Blank Why Governments Target Civil Society and What Can Be Done in Response A New Agenda Author Sarah E. Mendelson A Report of the CSIS Human Rights Initiative April 2015 About CSIS For over 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has worked to develop solutions to the world’s greatest policy challenges. Today, CSIS scholars are providing strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart a course toward a better world. CSIS is a nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full- time staff and large network of affiliated scholars conduct research and analysis and develop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Founded at the height of the Cold War by David M. Abshire and Admiral Arleigh Burke, CSIS was dedicated to finding ways to sustain American prominence and prosperity as a force for good in the world. Since 1962, CSIS has become one of the world’s preeminent international institutions focused on defense and security; regional stability; and transnational challenges ranging from energy and climate to global health and economic integration. Former U.S. senator Sam Nunn has chaired the CSIS Board of Trustees since 1999. Former deputy secretary of defense John J. Hamre became the Center’s president and chief executive officer in 2000. -

Constitutional Courts Versus Supreme Courts

SYMPOSIUM Constitutional courts versus supreme courts Lech Garlicki* Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/icon/article/5/1/44/722508 by guest on 30 September 2021 Constitutional courts exist in most of the civil law countries of Westem Europe, and in almost all the new democracies in Eastem Europe; even France has developed its Conseil Constitutionnel into a genuine constitutional jurisdiction. While their emergence may be regarded as one of the most successful improvements on traditional European concepts of democracy and the rule of law, it has inevitably given rise to questions about the distribution of power at the supreme judicial level. As constitutional law has come to permeate the entire structure of the legal system, it has become impossible to maintain a fi rm delimitation between the functions of the constitutional court and those of ordinary courts. This article looks at various confl icts arising between the higher courts of Germany, Italy, Poland, and France, and concludes that, in both positive and negative lawmaking, certain tensions are bound to exist as a necessary component of centralized judicial review. 1 . The Kelsenian model: Parallel supreme jurisdictions 1.1 The model The centralized Kelsenian system of judicial review is built on two basic assu- mptions. It concentrates the power of constitutional review within a single judicial body, typically called a constitutional court, and it situates that court outside the traditional structure of the judicial branch. While this system emerged more than a century after the United States’ system of diffused review, it has developed — particularly in Europe — into a widely accepted version of constitutional protection and control. -

1 the Rule of Law, Peace, Security and Development Muna Ndulo

The Rule of Law, Peace, Security and Development Muna Ndulo Muna Ndulo is an internationally recognized scholar in the fields of constitution making, governance and institution building, human rights and Foreign Direct Investments. He is a Professor of Law Cornell Law School and Director of the Cornell University’s Institute for African Development. He is Honorary Professor of Law, Faculty of Law, University of Cape Town. He was formerly Professor of Law and Dean of the School of Law, University of Zambia. Introduction This paper discusses the rule of law in the context of peace, security and development. It first examines the concept of “rule of law” and then looks at its relationship to security and development and its significance to democratic governance. At the outset it is important to point out that the “rule of law ” never has and does not mean “rule by law .” The later concept is devoid of values and in fact even the worst dictatorships and violators of human rights are organized through law albeit repressive law. One of the most important political and legal conceptions in good governance is the concept of the rule of law. In today’s world, nations from virtually every region recognize that the rule of law and the protection of human rights are critical factors in nation-building and good governance. Therefore the question that arises is this: what exactly is meant by the rule of law and in what ways can it assist in nation-building, the promotion of good governance, and the protection of human rights? The rule of law mandates the elimination of wide discretionary authority from government processes. -

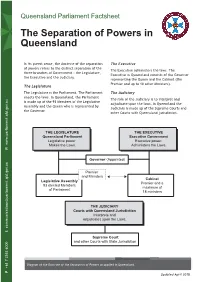

The Separation of Powers in Queensland

Queensland Parliament Factsheet The Separation of Powers in Queensland In its purest sense, the doctrine of the separation The Executive of powers refers to the distinct separation of the The Executive administers the laws. The three branches of Government - the Legislature, Executive in Queensland consists of the Governor the Executive and the Judiciary. representing the Queen and the Cabinet (the Premier and up to 18 other Ministers). The Legislature The Legislature is the Parliament. The Parliament The Judiciary enacts the laws. In Queensland, the Parliament The role of the Judiciary is to interpret and is made up of the 93 Members of the Legislative adjudicate upon the laws. In Queensland the Assembly and the Queen who is represented by Judiciary is made up of the Supreme Courts and the Governor. other Courts with Queensland jurisdiction. T ST T T Queensland Parliaent eutie oernent eislatie er ecutie er www.parliament.qld.gov.au aes the as dministers the as W Goernor inted Premier and inisters Cainet Leislatie ssel Premier and a elected emers maimum Parliament ministers T ourts with Queensland urisdition nterrets and adudicates un the as E [email protected] E [email protected] Supree ourt and ther urts ith tate urisdictin Diagram of the Doctrine of the Separation of Powers as applied in Queensland. +61 7 3553 6000 P Updated April 2018 Queensland Parliament Factsheet The Separation of Powers in Queensland Theoretically, each branch of government must be separate and not encroach upon the functions of the other branches. Furthermore, the persons who comprise these three branches must be kept separate and distinct. -

Classifying Systems of Constitutional Review: a Context-Specific Analysis

Indiana Journal of Constitutional Design Volume 5 Article 1 4-13-2020 Classifying Systems of Constitutional Review: A Context-Specific Analysis Samantha Lalisan Indiana University Maurer School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijcd Part of the Common Law Commons, Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Conflict of Laws Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Courts Commons, Dispute Resolution and Arbitration Commons, Jurisdiction Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, Law and Politics Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Lalisan, Samantha (2020) "Classifying Systems of Constitutional Review: A Context-Specific Analysis," Indiana Journal of Constitutional Design: Vol. 5 , Article 1. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijcd/vol5/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Journal of Constitutional Design by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Classifying Systems of Constitutional Review: A Context-Specific Analysis SAMANTHA LALISAN* “Access to the court is perhaps the most important ingredient in judicial power, because a party seeking to utilize judicial review as political insurance will only be able to do so if it can bring a case to court.”1 INTRODUCTION Europe’s experience with democratically elected fascist regimes leading to World War II is perhaps one of the most important developments for the establishment of new constitutional democracies. Post-war constitutional drafters sought to establish fundamental constitutional rights and to protect those rights through specialized constitutional courts.2 Many of these new democracies entrenched first-, second-, and third-generation rights into the constitution and included provisions to allow individuals access, direct or indirect, to the constitutional court to protect their rights through adjudication. -

Global Civil Society: an Overview

Global Civil Society An Overview Lester M. Salamon S. Wojciech Sokolowski Regina List The Johns Hopkins Comparative Nonprofit Sector Project The Johns Hopkins Comparative Nonprofit Sector Project Global Civil Society An Overview Lester M. Salamon S. Wojciech Sokolowski Regina List Copyright © 2003, Lester M. Salamon All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted for commercial purposes in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the copyright holder at the address below. Parts of this publication may be reproduced for noncommercial purposes so long as the authors and publisher are duly acknowledged. ISBN 1-886333-50-5 Center for Civil Society Studies Institute for Policy Studies The Johns Hopkins University 3400 N. Charles Street Baltimore, MD 21218-2688, USA Preface This report summarizes the basic empirical results of the latest phase of the Johns Hopkins Comparative Nonprofit Sector Project, the major effort we have had under way for a number of years to document the scope, structure, financing, and role of the nonprofit sector for the first time in various parts of the world, and to explain the resulting patterns that exist. This phase of project work has focused primarily on 15 countries in Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia, 13 of which are covered here. In addition to report- ing on these 13 countries, however, this report puts these findings into the broader context of our prior work. It therefore provides a portrait of the “civil society sector” in 35 countries throughout the world, including 16 advanced industrial countries, 14 developing countries, and 5 transitional countries of Central and Eastern Europe. -

The Constitution of Civil Society

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2000 The Constitution of Civil Society Mark V. Tushnet Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/232 75 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 379-415 (2000) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Constitutional Law Commons GEORGETOWN LAW Faculty Publications February 2010 The Constitution of Civil Society 75 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 379-415 (2000) Mark V. Tushnet Professor of Law Georgetown University Law Center [email protected] This paper can be downloaded without charge from: Scholarly Commons: http://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/232/ Posted with permission of the author THE CONSTITUTION OF CIVIL SOCIETY MARK TuSHNET* I. INTRODUCfION Recent interest in civil society appears to have been generated in part by concern that individuals acting directly in politics are unable to control the growth of their government or the policies it adopts. Mass society, it sometimes seems, deprives each of us of the resources necessary for responsible participation in our own political governance. We find ourselves unable to perform the dual tasks of democratic citizens: prodding our government to do what is necessary to ensure social well-being, and overseeing our government to ensure that it does not degenerate into an institution driven entirely from within that follows its own rather than our directives. Invigorating the institutions of civil society, it is thought, will serve an important democratic function by enhancing our capacity to act as responsible citizens.1 Those institutions will allow us simultaneously to stand apart from government, resisting and limiting its overreaching, and to engage in self-government through truly democratic institutions.2 * Carmack Waterhouse Professor of Constitutional Law, Georgetown University Law Center.