The Separation of Powers Doctrine: an Overview of Its Rationale and Application

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requir

Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Economics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Gérard Roland, Chair Professor Ernesto Dal Bó Associate Professor Fred Finan Associate Professor Yuriy Gorodnichenko Spring 2018 Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences Copyright 2018 by Weijia Li 1 Abstract Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li Doctor of Philosophy in Economics University of California, Berkeley Professor Gérard Roland, Chair This dissertation explores how to solve incentive problems in autocracies through institu- tional arrangements centered around political meritocracy. The question is fundamental, as merit-based rewards and promotion of politicians are the cornerstones of key authoritarian regimes such as China. Yet the grave dilemmas in bureaucratic governance are also well recognized. The three essays of the dissertation elaborate on the various solutions to these dilemmas, as well as problems associated with these solutions. Methodologically, the disser- tation utilizes a combination of economic modeling, original data collection, and empirical analysis. The first chapter investigates the puzzle why entrepreneurs invest actively in many autoc- racies where unconstrained politicians may heavily expropriate the entrepreneurs. With a game-theoretical model, I investigate how to constrain politicians through rotation of local politicians and meritocratic evaluation of politicians based on economic growth. The key finding is that, although rotation or merit-based evaluation alone actually makes the holdup problem even worse, it is exactly their combination that can form a credible constraint on politicians to solve the hold-up problem and thus encourages private investment. -

The Supreme Court's Treatment of Same-Sex Marriage in United States V. Windsor and Hollingsworth V. Perry: Analysis and Implications, Introduction

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 64 Issue 3 Article 6 2014 The Supreme Court's Treatment of Same-Sex Marriage in United States v. Windsor and Hollingsworth v. Perry: Analysis and Implications, Introduction Jonathan L. Entin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jonathan L. Entin, The Supreme Court's Treatment of Same-Sex Marriage in United States v. Windsor and Hollingsworth v. Perry: Analysis and Implications, Introduction, 64 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 823 (2014) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol64/iss3/6 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 64·Issue 3·2014 — Symposium — The Supreme Court’s Treatment of Same-Sex Marriage in United States v. Windsor and Hollingsworth v. Perry: Analysis and Implications INTRODUCTION Jonathan L. Entin† For many years, gay rights advocates focused primarily on overturning sodomy laws. The Supreme Court initially took a skeptical view of those efforts. In 1976, the Court summarily affirmed a ruling that upheld Virginia’s sodomy law.1 And a decade later, in Bowers v. Hardwick,2 the Court not only rejected a constitutional challenge to Georgia’s sodomy law but ridiculed the claim.3 That precedent lasted less than two decades before being overruled by Lawrence v. -

The Divergence of Standards of Conduct and Standards of Review in Corporate Law

Fordham Law Review Volume 62 Issue 3 Article 1 1993 The Divergence of Standards of Conduct and Standards of Review in Corporate Law Melvin Aron Eisenberg Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Melvin Aron Eisenberg, The Divergence of Standards of Conduct and Standards of Review in Corporate Law, 62 Fordham L. Rev. 437 (1993). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol62/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Divergence of Standards of Conduct and Standards of Review in Corporate Law Cover Page Footnote This Article is based on the Robert E. Levine Distinguished Lecture which I gave at Fordham Law School in 1993. I thank Joe Hinsey, Meir Dan-Cohen, and a number of my colleagues who attended a colloquium at which I presented an earlier version of this Article, for their valuable comments. This article is available in Fordham Law Review: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol62/iss3/1 ARTICLES THE DIVERGENCE OF STANDARDS OF CONDUCT AND STANDARDS OF REVIEW IN CORPORATE LAW MELVIN ARON EISENBERG * In this Article; ProfessorEisenberg examines how and why standardsof conduct and standards of review diverge in corporate law. Professor Eisenberg analyzes the relevant standardsof conduct and review that apply in a number of corporate law contexts. -

The Parliament

The Parliament is composed of 3 distinct elements,the Queen1 the Senate and the House of Representatives.2 These 3 elements together characterise the nation as being a constitutional monarchy, a parliamentary democracy and a federation. The Constitution vests in the Parliament the legislative power of the Common- wealth. The legislature is bicameral, which is the term commoniy used to indicate a Par- liament of 2 Houses. Although the Queen is nominally a constituent part of the Parliament the Consti- tution immediately provides that she appoint a Governor-General to be her representa- tive in the Commonwealth.3 The Queen's role is little more than titular as the legislative and executive powers and functions of the Head of State are vested in the Governor- General by virtue of the Constitution4, and by Letters Patent constituting the Office of Governor-General.5 However, while in Australia, the Sovereign has performed duties of the Governor-General in person6, and in the event of the Queen being present to open Parliament, references to the Governor-General in the relevant standing orders7 are to the extent necessary read as references to the Queen.s The Royal Style and Titles Act provides that the Queen shall be known in Australia and its Territories as: Elizabeth the Second, by the Grace of God Queen of Australia and Her other Realms and Territories, Head of the Commonwealth.* There have been 19 Governors-General of Australia10 since the establishment of the Commonwealth, 6 of whom (including the last 4) have been Australian born. The Letters Patent, of 29 October 1900, constituting the office of Governor- General, 'constitute, order, and declare that there shall be a Governor-General and Commander-in-Chief in and over' the Commonwealth. -

Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: a Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation Amy J

American University International Law Review Volume 10 | Issue 4 Article 6 1995 Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: A Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation Amy J. Weisman Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Weisman, Amy J. "Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: A Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation." American University International Law Review 10, no. 4 (1995): 1365-1398. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SEPARATION OF POWERS IN POST- COMMUNIST GOVERNMENT: A CONSTITUTIONAL CASE STUDY OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION Amy J. Weisman* INTRODUCTION This comment explores the myriad of issues related to constructing and maintaining a stable, democratic, and constitutionally based govern- ment in the newly independent Russian Federation. Russia recently adopted a constitution that expresses a dedication to the separation of powers doctrine.' Although this constitution represents a significant step forward in the transition from command economy and one-party rule to market economy and democratic rule, serious violations of the accepted separation of powers doctrine exist. A thorough evaluation of these violations, and indeed, the entire governmental structure of the Russian Federation is necessary to assess its chances for a successful and peace- ful transition and to suggest alternative means for achieving this goal. -

Terms of Service for Members of the House of Representatives in the 117Th Congress

Terms of Service for Members of the House of Representatives in the 117th Congress October 1, 2021 The table below includes Members of the House of Representatives sorted by number of terms of service (in descending order by beginning of service) and then alphabetically by last name. Bold text denotes individuals elected in special elections. Italic text indicates non-consecutive service. Terms of Service for Representatives Last name First name Terms of State Party Congresses (inclusive) Beginning of service present service Young Don 25 AK Republican 93rd to 117th March 6, 1973 Rogers Harold 21 KY Republican 97th to 117th January 3, 1981 Smith Christopher H. 21 NJ Republican 97th to 117th January 3, 1981 Hoyer Steny H. 21 MD Democrat 97th to 117th May 19, 1981 Kaptur Marcy 20 OH Democrat 98th to 117th January 3, 1983 DeFazio Peter A. 18 OR Democrat 100th to 117th January 3, 1987 Upton Fred 18 MI Republican 100th to 117th January 3, 1987 Pelosi Nancy 18 CA Democrat 100th to 117th June 2, 1987 Pallone Frank, Jr. 18 NJ Democrat 100th to 117th November 8, 1988 Neal Richard E. 17 MA Democrat 101st to 117th January 3, 1989 100th to 103rd; 105th Price David E. 17 NC Democrat to 117th January 3, 1997 DeLauro Rosa L. 16 CT Democrat 102nd to 117th January 3, 1991 Waters Maxine 16 CA Democrat 102nd to 117th January 3, 1991 Nadler Jerrold 16 NY Democrat 102nd to 117th November 3, 1992 98th to 103rd; 108th Cooper Jim 16 TN Democrat to 117th January 3, 2003 Bishop Sanford D., Jr. -

The Political Question Doctrine: Justiciability and the Separation of Powers

The Political Question Doctrine: Justiciability and the Separation of Powers Jared P. Cole Legislative Attorney December 23, 2014 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R43834 The Political Question Doctrine: Justiciability and the Separation of Powers Summary Article III of the Constitution restricts the jurisdiction of federal courts to deciding actual “Cases” and “Controversies.” The Supreme Court has articulated several “justiciability” doctrines emanating from Article III that restrict when federal courts will adjudicate disputes. One justiciability concept is the political question doctrine, according to which federal courts will not adjudicate certain controversies because their resolution is more proper within the political branches. Because of the potential implications for the separation of powers when courts decline to adjudicate certain issues, application of the political question doctrine has sparked controversy. Because there is no precise test for when a court should find a political question, however, understanding exactly when the doctrine applies can be difficult. The doctrine’s origins can be traced to Chief Justice Marshall’s opinion in Marbury v. Madison; but its modern application stems from Baker v. Carr, which provides six independent factors that can present political questions. These factors encompass both constitutional and prudential considerations, but the Court has not clearly explained how they are to be applied. Further, commentators have disagreed about the doctrine’s foundation: some see political questions as limited to constitutional grants of authority to a coordinate branch of government, while others see the doctrine as a tool for courts to avoid adjudicating an issue best resolved outside of the judicial branch. Supreme Court case law after Baker fails to resolve the matter. -

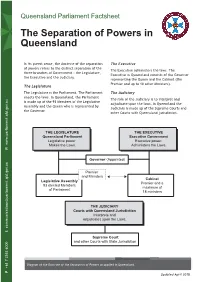

The Separation of Powers in Queensland

Queensland Parliament Factsheet The Separation of Powers in Queensland In its purest sense, the doctrine of the separation The Executive of powers refers to the distinct separation of the The Executive administers the laws. The three branches of Government - the Legislature, Executive in Queensland consists of the Governor the Executive and the Judiciary. representing the Queen and the Cabinet (the Premier and up to 18 other Ministers). The Legislature The Legislature is the Parliament. The Parliament The Judiciary enacts the laws. In Queensland, the Parliament The role of the Judiciary is to interpret and is made up of the 93 Members of the Legislative adjudicate upon the laws. In Queensland the Assembly and the Queen who is represented by Judiciary is made up of the Supreme Courts and the Governor. other Courts with Queensland jurisdiction. T ST T T Queensland Parliaent eutie oernent eislatie er ecutie er www.parliament.qld.gov.au aes the as dministers the as W Goernor inted Premier and inisters Cainet Leislatie ssel Premier and a elected emers maimum Parliament ministers T ourts with Queensland urisdition nterrets and adudicates un the as E [email protected] E [email protected] Supree ourt and ther urts ith tate urisdictin Diagram of the Doctrine of the Separation of Powers as applied in Queensland. +61 7 3553 6000 P Updated April 2018 Queensland Parliament Factsheet The Separation of Powers in Queensland Theoretically, each branch of government must be separate and not encroach upon the functions of the other branches. Furthermore, the persons who comprise these three branches must be kept separate and distinct. -

OPINION and DENNIS HOLLINGSWORTH; GAIL J

FOR PUBLICATION UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT KRISTIN M. PERRY; SANDRA B. STIER; PAUL T. KATAMI; JEFFREY J. ZARRILLO, Plaintiffs-Appellees, CITY AND COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO, Intervenor-Plaintiff-Appellee, v. EDMUND G. BROWN, JR., in his official capacity as Governor of California; KAMALA D. HARRIS, in her official capacity as Attorney General of California; MARK B. HORTON, in his official capacity as Director of the California Department of Public Health & State Registrar of Vital Statistics; LINETTE SCOTT, in her official capacity as Deputy Director of Health Information & Strategic Planning for the California Department of Public Health; PATRICK O’CONNELL, in his official capacity as Clerk-Recorder for the County of Alameda; DEAN C. LOGAN, in his official capacity as Registrar-Recorder/County Clerk for the County of Los Angeles, Defendants, 1569 1570 PERRY v. BROWN HAK-SHING WILLIAM TAM, Intervenor-Defendant, and DENNIS HOLLINGSWORTH; GAIL J. No. 10-16696 KNIGHT; MARTIN F. GUTIERREZ; D.C. No. MARK A. JANSSON; 3:09-cv-02292- PROTECTMARRIAGE.COM-YES ON 8, VRW A PROJECT OF CALIFORNIA RENEWAL, as official proponents of Proposition 8, Intervenor-Defendants-Appellants. KRISTIN M. PERRY; SANDRA B. STIER; PAUL T. KATAMI; JEFFREY J. ZARRILLO, Plaintiffs-Appellees, CITY AND COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO, Intervenor-Plaintiff-Appellee, v. EDMUND G. BROWN, JR., in his official capacity as Governor of California; KAMALA D. HARRIS, in her official capacity as Attorney General of California; MARK B. HORTON, in his official capacity as Director of the California Department of Public Health & State Registrar of Vital Statistics; PERRY v. BROWN 1571 LINETTE SCOTT, in her official capacity as Deputy Director of Health Information & Strategic Planning for the California Department of Public Health; PATRICK O’CONNELL, in his official capacity as Clerk-Recorder for the County of Alameda; DEAN C. -

United States Government Primer

1 United States Government Primer United States Government Primer Consortium for Ocean Leadership – 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 The Three Branches of Government 3 Legislative Branch 4 U S Senate 5 U S House of Representatives 5 How a Bill Becomes Law 5 Committees with Jurisdiction over Ocean Research and Policy 8 Creating and Funding Federal Agencies 9 Executive Branch 10 Federal Agencies Involved in Ocean Research and Policy 11 Judicial Branch 12 Major Ocean and Coastal Policy Legislation 13 Videos (by Crash Course on Government and Politics) 15 United States Government Primer Consortium for Ocean Leadership – 3 INTRODUCTION This primer outlines the key points of the U S political system, including the three branches of the federal government prescribed by the Constitution The legislative branch includes the Senate and the House of Representatives and is charged with drafting and approving laws (see Schoolhouse Rock video) The executive branch, including the president and his/her Cabinet, implements and enforces laws Finally, the judicial branch contains the court system that interprets and applies laws The basics of the political process are explained in the following summaries THE THREE BRANCHES OF GOVERNMENT The federal government consists of three parts: legislative branch, executive branch, and judicial branch Together, they function to provide a system of lawmaking and enforcement based on a system of checks and balances The separation of powers through three different branches of government is intended to ensure that no individual, or body of government, can become too powerful This helps protect individual freedoms in addition to preventing the government from abusing its power This separation of power is described in the first three articles of the Constitution 3Branches of Government The U.S. -

Unicameralism and the Indiana Constitutional Convention of 1850 Val Nolan, Jr.*

DOCUMENT UNICAMERALISM AND THE INDIANA CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION OF 1850 VAL NOLAN, JR.* Bicameralism as a principle of legislative structure was given "casual, un- questioning acceptance" in the state constitutions adopted in the nineteenth century, states Willard Hurst in his recent study of main trends in the insti- tutional development of American law.1 Occasioning only mild and sporadic interest in the states in the post-Revolutionary period,2 problems of legislative * A.B. 1941, Indiana University; J.D. 1949; Assistant Professor of Law, Indiana Uni- versity School of Law. 1. HURST, THE GROWTH OF AMERICAN LAW, THE LAW MAKERS 88 (1950). "O 1ur two-chambered legislatures . were adopted mainly by default." Id. at 140. During this same period and by 1840 many city councils, unicameral in colonial days, became bicameral, the result of easy analogy to state governmental forms. The trend was reversed, and since 1900 most cities have come to use one chamber. MACDONALD, AmER- ICAN CITY GOVERNMENT AND ADMINISTRATION 49, 58, 169 (4th ed. 1946); MUNRO, MUNICIPAL GOVERN-MENT AND ADMINISTRATION C. XVIII (1930). 2. "[T]he [American] political theory of a second chamber was first formulated in the constitutional convention held in Philadelphia in 1787 and more systematically developed later in the Federalist." Carroll, The Background of Unicameralisnl and Bicameralism, in UNICAMERAL LEGISLATURES, THE ELEVENTH ANNUAL DEBATE HAND- BOOK, 1937-38, 42 (Aly ed. 1938). The legislature of the confederation was unicameral. ARTICLES OF CONFEDERATION, V. Early American proponents of a bicameral legislature founded their arguments on theoretical grounds. Some, like John Adams, advocated a second state legislative house to represent property and wealth. -

Separation of Powers and the Independence of Constitutional Courts and Equivalent Bodies

1 Christoph Grabenwarter Separation of Powers and the Independence of Constitutional Courts and Equivalent Bodies Keynote Speech 16 January 2011 2nd Congress of the World Conference on Constitutional Justice, Rio de Janeiro 1. Introduction Separation of Power is one of the basic structural principles of democratic societies. It was already discussed by ancient philosophers, deep analysis can be found in medieval political and philosophical scientific work, and we base our contemporary discussion on legal theory that has been developed in parallel to the emergence of democratic systems in Northern America and in Europe in the 18 th Century. Separation of Powers is not an end in itself, nor is it a simple tool for legal theorists or political scientists. It is a basic principle in every democratic society that serves other purposes such as freedom, legality of state acts – and independence of certain organs which exercise power delegated to them by a specific constitutional rule. When the organisers of this World Conference combine the concept of the separation of powers with the independence of constitutional courts, they address two different aspects. The first aspect has just been mentioned. The independence of constitutional courts is an objective of the separation of powers, independence is its result. This is the first aspect, and perhaps the aspect which first occurs to most of us. The second aspect deals with the reverse relationship: independence of constitutional courts as a precondition for the separation of powers. Independence enables constitutional courts to effectively control the respect for the separation of powers. As a keynote speech is not intended to provide a general report on the results of the national reports, I would like to take this opportunity to discuss certain questions raised in the national reports and to add some thoughts that are not covered by the questionnaire sent out a few months ago, but are still thoughts on the relationship between the constitutional principle and the independence of constitutional judges.