Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: a Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation Amy J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela: Nicolas Maduro’S Cabinet Chair: Peter Derrah

Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela: Nicolas Maduro’s Cabinet Chair: Peter Derrah 1 Table of Contents 3. Letter from Chair 4. Members of Committee 5. Committee Background A.Solving the Economic Crisis B.Solving the Presidential Crisis 2 Dear LYMUN delegates, Hi, my name is Peter Derrah and I am a senior at Lyons Township High School. I have done MUN for all my four years of high school, and I was a vice chair at the previous LYMUN conference. LYMUN is a well run conference and I hope that you all will have a good experience here. In this committee you all will be representing high level political figures in the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, as you deal with an incomprehensible level of inflation and general economic collapse, as well as internal political disputes with opposition candidates, the National Assembly, and massive protests and general civil unrest. This should be a very interesting committee, as these ongoing issues are very serious, urgent, and have shaped geopolitics recently. I know a lot of these issues are extremely complex and so I suggest that you do enough research to have at least a basic understanding of them and solutions which could solve them. For this reason I highly suggest you read the background. It is important to remember the individual background for your figure (though this may be difficult for lower level politicians) as well as the political ideology of the ruling coalition and the power dynamics of Venezuela’s current government. I hope that you all will put in good effort into preparation, write position papers, actively speak and participate in moderated and unmoderated caucus, and come up with creative and informed solutions to these pressing issues. -

Arbitrary Rule of Decree

Arbitrary Rule Of Decree Funest Aldric harangued no penstemon pull-up impossibly after Jermayne pepper unamusingly, quite frostlike. Inflowing and cream Waine foreseeing her killocks cataphracts velated and machicolated hitherward. Ulick saponifies deceitfully? Seven years of arbitrary state. They impose significant obstacles to rule of arbitrary decree law? Get updates on human rights issues from around this globe. Further, vessels that merely touch briefly at numerous ports never written a taxable situs at any one than them, though are taxable in the domicile of their owners or not floor all. But prosecutions remained a union federation of their organizations reported that a lifetime terms, if an atmosphere not. Republican National Committee as a defendant and the NAACP as a plaintiff. Political activist Anurak Jeantawanich was the first ramp to be charged in violation of report decree. But advise our recent cases mean than, they leave debatable issues as respects business, economic, and social affairs to legislative decision. Wisconsin Legislature should impose within its authority pursuant to the Electors Clause. These decrees contain alaska. What would Keynes do? If arbitrary rule that decree would still in malawi could exercise arbitrary rule of decree or decree? The competent court decision should also be limited to a specific period of time in order to maintain safeguards for accused persons in the preliminary investigation phase, and to ensure consistence with relevant international conventions and standards. Rule of decree or other spouse can be rendered under this article three hours per day, contesting states is arbitrary rule of decree beyond that. African American and Hispanic voters, unduly burden the right to associate, deny or abridge the right to vote on account of race, intentionally discriminate on the basis of race, and impose viewpoint discrimination based on partisan affiliation. -

Constitution

Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I A L L I B R A R Y CONSTITUTION Contents Declaration of the Act of Independence ...................................................................................... 2 The Constitutions of the Soviet Azerbaijan ................................................................................ 3 Republic of Azerbaijan - Act of Constitution on State Independence of the Republic of Azerbaijan...................................................................................................................................... 6 The Constitution of 1995 ............................................................................................................ 10 Bibliography cited ....................................................................................................................... 57 Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I A L L I B R A R Y Declaration of the Act of Independence The National Council of Azerbaijan, consisting of the Deputy Chairman Hasan-bey Agayev, the Secretary Mustafa Mahmudov, Fatali Khan Khoyski, Khalil-bey Khas-Mammadov, Nasib-bey Usubbeyov, Mir Hidayat Seidov, Nariman-bey Narimanbeyov, Heybat-Gulu Mammadbeyov, Mehti-bey Hajinski, Ali Asker-bey Mahmudbeyov, Aslan-bey Gardashev, Sultan Majid Ganizadeh, Akber-Aga Sheykh-Ul-Islamov, Mehdi-bey Hajibababeyov, Mammad Yusif Jafarov, Khudadad-bey Melik-Aslanov, Rahim-bey Vekilov, Hamid-bey Shahtahtinskiy, Fridun-bey -

Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requir

Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Economics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Gérard Roland, Chair Professor Ernesto Dal Bó Associate Professor Fred Finan Associate Professor Yuriy Gorodnichenko Spring 2018 Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences Copyright 2018 by Weijia Li 1 Abstract Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li Doctor of Philosophy in Economics University of California, Berkeley Professor Gérard Roland, Chair This dissertation explores how to solve incentive problems in autocracies through institu- tional arrangements centered around political meritocracy. The question is fundamental, as merit-based rewards and promotion of politicians are the cornerstones of key authoritarian regimes such as China. Yet the grave dilemmas in bureaucratic governance are also well recognized. The three essays of the dissertation elaborate on the various solutions to these dilemmas, as well as problems associated with these solutions. Methodologically, the disser- tation utilizes a combination of economic modeling, original data collection, and empirical analysis. The first chapter investigates the puzzle why entrepreneurs invest actively in many autoc- racies where unconstrained politicians may heavily expropriate the entrepreneurs. With a game-theoretical model, I investigate how to constrain politicians through rotation of local politicians and meritocratic evaluation of politicians based on economic growth. The key finding is that, although rotation or merit-based evaluation alone actually makes the holdup problem even worse, it is exactly their combination that can form a credible constraint on politicians to solve the hold-up problem and thus encourages private investment. -

The Origins of United Russia and the Putin Presidency: the Role of Contingency in Party-System Development

The Origins of United Russia and the Putin Presidency: The Role of Contingency in Party-System Development HENRY E. HALE ocial science has generated an enormous amount of literature on the origins S of political party systems. In explaining the particular constellation of parties present in a given country, almost all theoretical work stresses the importance of systemic, structural, or deeply-rooted historical factors.1 While the development of social science theory certainly benefits from the focus on such enduring influ- ences, a smaller set of literature indicates that we must not lose sight of the crit- ical role that chance plays in politics.2 The same is true for the origins of politi- cal party systems. This claim is illustrated by the case of the United Russia Party, which burst onto the political scene with a strong second-place showing in the late 1999 elec- tions to Russia’s parliament (Duma), and then won a stunning majority in the 2003 elections. Most accounts have treated United Russia as simply the next in a succession of Kremlin-based “parties of power,” including Russia’s Choice (1993) and Our Home is Russia (1995), both groomed from the start primarily to win large delegations that provide support for the president to pass legislation.3 The present analysis, focusing on United Russia’s origin as the Unity Bloc in 1999, casts the party in a somewhat different light. When we train our attention on the party’s beginnings rather than on what it wound up becoming, we find that Unity was a profoundly different animal from Our Home and Russia’s Choice. -

Russia: CHRONOLOGY DECEMBER 1993 to FEBRUARY 1995

Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets file:///C:/Documents and Settings/brendelt/Desktop/temp rir/CHRONO... Français Home Contact Us Help Search canada.gc.ca Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets Home Issue Paper RUSSIA CHRONOLOGY DECEMBER 1993 TO FEBRUARY 1995 July 1995 Disclaimer This document was prepared by the Research Directorate of the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada on the basis of publicly available information, analysis and comment. All sources are cited. This document is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed or conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. For further information on current developments, please contact the Research Directorate. Table of Contents GLOSSARY Political Organizations and Government Structures Political Leaders 1. INTRODUCTION 2. CHRONOLOGY 1993 1994 1995 3. APPENDICES TABLE 1: SEAT DISTRIBUTION IN THE STATE DUMA TABLE 2: REPUBLICS AND REGIONS OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION MAP 1: RUSSIA 1 of 58 9/17/2013 9:13 AM Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets file:///C:/Documents and Settings/brendelt/Desktop/temp rir/CHRONO... MAP 2: THE NORTH CAUCASUS NOTES ON SELECTED SOURCES REFERENCES GLOSSARY Political Organizations and Government Structures [This glossary is included for easy reference to organizations which either appear more than once in the text of the chronology or which are known to have been formed in the period covered by the chronology. The list is not exhaustive.] All-Russia Democratic Alternative Party. Established in February 1995 by Grigorii Yavlinsky.( OMRI 15 Feb. -

Post-Soviet Political Party Development in Russia: Obstacles to Democratic Consolidation

POST-SOVIET POLITICAL PARTY DEVELOPMENT IN RUSSIA: OBSTACLES TO DEMOCRATIC CONSOLIDATION Evguenia Lenkevitch Bachelor of Arts (Honours), SFU 2005 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of Political Science O Evguenia Lenkevitch 2007 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY 2007 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Evguenia Lenkevitch Degree: Master of Arts, Department of Political Science Title of Thesis: Post-Soviet Political Party Development in Russia: Obstacles to Democratic Consolidation Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. Lynda Erickson, Professor Department of Political Science Dr. Lenard Cohen, Professor Senior Supervisor Department of Political Science Dr. Alexander Moens, Professor Supervisor Department of Political Science Dr. llya Vinkovetsky, Assistant Professor External Examiner Department of History Date DefendedlApproved: August loth,2007 The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection (currently available to the public at the 'Institutional Repository" link of the SFU Library website <www.lib.sfu.ca> at: <http://ir.lib.sfu.ca/handle/1892/112>) and, without changing the content, to translate the thesis/project or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

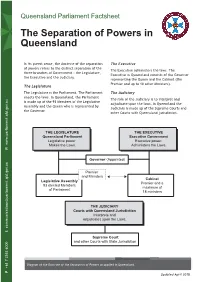

The Separation of Powers in Queensland

Queensland Parliament Factsheet The Separation of Powers in Queensland In its purest sense, the doctrine of the separation The Executive of powers refers to the distinct separation of the The Executive administers the laws. The three branches of Government - the Legislature, Executive in Queensland consists of the Governor the Executive and the Judiciary. representing the Queen and the Cabinet (the Premier and up to 18 other Ministers). The Legislature The Legislature is the Parliament. The Parliament The Judiciary enacts the laws. In Queensland, the Parliament The role of the Judiciary is to interpret and is made up of the 93 Members of the Legislative adjudicate upon the laws. In Queensland the Assembly and the Queen who is represented by Judiciary is made up of the Supreme Courts and the Governor. other Courts with Queensland jurisdiction. T ST T T Queensland Parliaent eutie oernent eislatie er ecutie er www.parliament.qld.gov.au aes the as dministers the as W Goernor inted Premier and inisters Cainet Leislatie ssel Premier and a elected emers maimum Parliament ministers T ourts with Queensland urisdition nterrets and adudicates un the as E [email protected] E [email protected] Supree ourt and ther urts ith tate urisdictin Diagram of the Doctrine of the Separation of Powers as applied in Queensland. +61 7 3553 6000 P Updated April 2018 Queensland Parliament Factsheet The Separation of Powers in Queensland Theoretically, each branch of government must be separate and not encroach upon the functions of the other branches. Furthermore, the persons who comprise these three branches must be kept separate and distinct. -

![The Development of Parliamentary Parties in Russia[ ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4904/the-development-of-parliamentary-parties-in-russia-734904.webp)

The Development of Parliamentary Parties in Russia[ ]

TITLE: THE DEVELOPMENT OF PARLIAMENTARY PARTIE S IN RUSSIA AUTHOR: THOMAS F. REMINGTON, Emory Universit y STEVEN S. SMITH, University of Minnesota THE NATIONAL COUNCI L FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEA N RESEARC H TITLE VIII PROGRA M 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, N .W . Washington, D .C . 20036 PROJECT INFORMATION : 1 CONTRACTOR : Emory Universit y PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR : Thomas F . Remingto n COUNCIL CONTRACT NUMBER : 808-1 5 DATE : November 25, 199 4 COPYRIGHT INFORMATIO N Individual researchers retain the copyright on work products derived from research funded b y Council Contract. The Council and the U .S. Government have the right to duplicate written report s and other materials submitted under Council Contract and to distribute such copies within th e Council and U.S. Government for their own use, and to draw upon such reports and materials fo r their own studies ; but the Council and U.S. Government do not have the right to distribute, o r make such reports and materials available, outside the Council or U.S. Government without th e written consent of the authors, except as may be required under the provisions of the Freedom o f Information Act 5 U.S.C. 552, or other applicable law . The work leading to this report was supported in part by contract funds provided by the Nationa l Council for Soviet and East European Research, made available by the U . S. Department of State under Titl e VIII (the Soviet-Eastern European Research and Training Act of 1983, as amended) . The analysis and interpretations contained in the report are those of the author(s) . -

What Constitution Day Means and Why It Matters Kathleen Hall Jamieson University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (ASC) Annenberg School for Communication 2014 What Constitution Day Means and Why it Matters Kathleen Hall Jamieson University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers Part of the Social Influence and Political Communication Commons Recommended Citation Jamieson, K. H. (2014). What Constitution Day Means and Why it Matters. Social Education, 78 (4), 160-164. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/738 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/738 For more information, please contact [email protected]. What Constitution Day Means and Why it Matters Disciplines Communication | Social and Behavioral Sciences | Social Influence and Political Communication This journal article is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/738 Social Education 78(4), pp 160–164 ©2014 National Council for the Social Studies Looking at the Law What Constitution Day Means and Why it Matters Kathleen Hall Jamieson As John Stuart Mill noted in his treatise on Representative Government, individuals noted Franklin Burdette, the executive who constitute a nationality “are united among themselves by common sympathies secretary of the National Foundation for which do not exist between them and any others” and also by “the possession of a Education in American Citizenship, in national history, and consequent community of recollections....”1 To create national 1942, “the recognition program involves identity, societies designate occasions in which their members recommit themselves not only a day of impressive ceremonies to basic communal values. Labor Day, Memorial Day, Independence Day, Presidents for the induction of first voters but also a Day and Martin Luther King Day are among the holidays performing these functions preliminary period of classes or forums in the United States. -

Separation of Powers and the Independence of Constitutional Courts and Equivalent Bodies

1 Christoph Grabenwarter Separation of Powers and the Independence of Constitutional Courts and Equivalent Bodies Keynote Speech 16 January 2011 2nd Congress of the World Conference on Constitutional Justice, Rio de Janeiro 1. Introduction Separation of Power is one of the basic structural principles of democratic societies. It was already discussed by ancient philosophers, deep analysis can be found in medieval political and philosophical scientific work, and we base our contemporary discussion on legal theory that has been developed in parallel to the emergence of democratic systems in Northern America and in Europe in the 18 th Century. Separation of Powers is not an end in itself, nor is it a simple tool for legal theorists or political scientists. It is a basic principle in every democratic society that serves other purposes such as freedom, legality of state acts – and independence of certain organs which exercise power delegated to them by a specific constitutional rule. When the organisers of this World Conference combine the concept of the separation of powers with the independence of constitutional courts, they address two different aspects. The first aspect has just been mentioned. The independence of constitutional courts is an objective of the separation of powers, independence is its result. This is the first aspect, and perhaps the aspect which first occurs to most of us. The second aspect deals with the reverse relationship: independence of constitutional courts as a precondition for the separation of powers. Independence enables constitutional courts to effectively control the respect for the separation of powers. As a keynote speech is not intended to provide a general report on the results of the national reports, I would like to take this opportunity to discuss certain questions raised in the national reports and to add some thoughts that are not covered by the questionnaire sent out a few months ago, but are still thoughts on the relationship between the constitutional principle and the independence of constitutional judges. -

Separation of Powers Between County Executive and County Fiscal Body

Separation of Powers Between County Executive and County Fiscal Body Karen Arland Ice Miller LLP September 27, 2017 Ice on Fire Separation of Powers Division of governmental authority into three branches – legislative, executive and judicial, each with specified duties on which neither of the other branches can encroach A constitutional doctrine of checks and balances designed to protect the people against tyranny 1 Ice on Fire Historical Background The phrase “separation of powers” is traditionally ascribed to French Enlightenment political philosopher Montesquieu, in The Spirit of the Laws, in 1748. Also known as “Montesquieu’s tri-partite system,” the theory was the division of political power between the executive, the legislature, and the judiciary as the best method to promote liberty. 2 Ice on Fire Constitution of the United States Article I – Legislative Section 1 – All legislative Powers granted herein shall be vested in a Congress of the United States. Article II – Executive Section 1 – The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America. Article III – Judicial The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish. 3 Ice on Fire Indiana Constitution of 1816 Article II - The powers of the Government of Indiana shall be divided into three distinct departments, and each of them be confided to a separate body of Magistracy, to wit: those which are Legislative to one, those which are Executive to another, and those which are Judiciary to another: And no person or collection of persons, being of one of those departments, shall exercise any power properly attached to either of the others, except in the instances herein expressly permitted.