Federalism, Separation of Powers, and Individual Liberties

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

War and the Constitutional Text John C

War and the Constitutional Text John C. Yoo∗ In a series of articles, I have criticized the view that the original under- standing of the Constitution requires that Congress provide its authorization before the United States can engage in military hostilities.1 This “pro- Congress” position ignores the constitutional text and structure, errs in in- terpreting the ratification history of the Constitution, and cannot account for the practice of the three branches of government. Instead of the rigid proc- ess advocated by scholars such as Louis Henkin, John Hart Ely, Louis Fisher, Michael Glennon, and Harold Koh,2 I have argued that the Constitu- tion creates a flexible system of war powers. That system provides the president with significant initiative as commander-in-chief, while reserving to Congress ample authority to check executive policy through its power of the purse. In this scheme, the Declare War Clause confers on Congress a ju- ridical power, one that both defines the state of international legal relations ∗ Professor of Law, University of California at Berkeley School of Law (Boalt Hall) (on leave); Deputy Assistant Attorney General, Office of Legal Counsel, United States Department of Justice. The views expressed here are those of the author alone and do not represent the views of the Department of Justice. I express my deep appreciation for the advice and assistance of James C. Ho in preparing this response. Robert Delahunty, Jack Goldsmith, and Sai Prakash provided helpful comments on the draft. 1 See John C. Yoo, Kosovo, War Powers, and the Multilateral Future, 148 U Pa L Rev 1673, 1686–1704 (2000) (discussing the original understanding of war powers in the context of the Kosovo conflict); John C. -

Prince Edward Island and Confederation 1863-1873

CCHA, Report, 28 (1961), 25-30 Prince Edward Island and Confederation 1863-1873 Francis William Pius BOLGER, Ph.D. St. Dunstan’s University, Charlottetown The idea of Confederation did not receive serious consideration in Prince Edward Island prior to the year 1863. Ten more years elapsed before the subject of union with the British North American Colonies moved into the non-academic and practical sphere. The position of the Island in the Confederation negotiations illustrated in large measure the characteristics of its politics and its attitude to distant administrations. This attitude might best be described simply as a policy of exclusiveness. The history of the Confederation negotiations in Prince Edward Island consisted of the interplay of British, Canadian, and Maritime influences upon this policy. It is the purpose of this paper to tell the story of Confederation in Prince Edward Island from 1863 to 1873. The policy of exclusiveness, which characterized Prince Erward Island’s attitude to Confederation, was clearly revealed in the political arena. The Islanders had a profound respect for local self-government. They enjoyed their political independence, particularly after the attainment of responsible government in 1851, and did not wish to see a reduction in the significance of their local institutions. They realized, moreover, that they would have an insignificant voice in a centralized legislature, and as a result they feared that their local needs would be disregarded. Finally, previous frustrating experience with the Imperial government with respect to the settlement of the land question on the Island had taught the Islanders that it was extremely hazardous to trust the management of local problems to distant and possibly unsympathetic administrations. -

Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requir

Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Economics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Gérard Roland, Chair Professor Ernesto Dal Bó Associate Professor Fred Finan Associate Professor Yuriy Gorodnichenko Spring 2018 Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences Copyright 2018 by Weijia Li 1 Abstract Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li Doctor of Philosophy in Economics University of California, Berkeley Professor Gérard Roland, Chair This dissertation explores how to solve incentive problems in autocracies through institu- tional arrangements centered around political meritocracy. The question is fundamental, as merit-based rewards and promotion of politicians are the cornerstones of key authoritarian regimes such as China. Yet the grave dilemmas in bureaucratic governance are also well recognized. The three essays of the dissertation elaborate on the various solutions to these dilemmas, as well as problems associated with these solutions. Methodologically, the disser- tation utilizes a combination of economic modeling, original data collection, and empirical analysis. The first chapter investigates the puzzle why entrepreneurs invest actively in many autoc- racies where unconstrained politicians may heavily expropriate the entrepreneurs. With a game-theoretical model, I investigate how to constrain politicians through rotation of local politicians and meritocratic evaluation of politicians based on economic growth. The key finding is that, although rotation or merit-based evaluation alone actually makes the holdup problem even worse, it is exactly their combination that can form a credible constraint on politicians to solve the hold-up problem and thus encourages private investment. -

The Meaning of the Federalist Papers

English-Language Arts: Operational Lesson Title: The Meaning of the Federalist Papers Enduring Understanding: Equality is necessary for democracy to thrive. Essential Question: How did the constitutional system described in The Federalist Papers contribute to our national ideas about equality? Lesson Overview This two-part lesson explores the Federalist Papers. First, students engage in a discussion about how they get information about current issues. Next, they read a short history of the Federalist Papers and work in small groups to closely examine the text. Then, student pairs analyze primary source manuscripts concerning the Federalist Papers and relate these documents to what they have already learned. In an optional interactive activity, students now work in small groups to research a Federalist or Anti-Federalist and role-play this person in a classroom debate on the adoption of the Constitution. Extended writing and primary source activities follow that allow students to use their understanding of the history and significance of the Federalist Papers. Lesson Objectives Students will be able to: • Explain arguments for the necessity of a Constitution and a bill of rights. • Define democracy and republic and explain James Madison’s use of these terms. • Describe the political philosophy underpinning the Constitution as specified in the Federalist Papers using primary source examples. • Discuss and defend the ideas of the leading Federalists and Anti-Federalists on several issues in a classroom role-play debate. (Optional Activity) • Develop critical thinking, writing skills, and facility with textual evidence by examining the strengths of either Federalism or Anti-Federalism. (Optional/Extended Activities) • Use both research skills and creative writing techniques to draft a dialogue between two contemporary figures that reflects differences in Federalist and Anti-Federalist philosophies. -

Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: a Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation Amy J

American University International Law Review Volume 10 | Issue 4 Article 6 1995 Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: A Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation Amy J. Weisman Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Weisman, Amy J. "Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: A Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation." American University International Law Review 10, no. 4 (1995): 1365-1398. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SEPARATION OF POWERS IN POST- COMMUNIST GOVERNMENT: A CONSTITUTIONAL CASE STUDY OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION Amy J. Weisman* INTRODUCTION This comment explores the myriad of issues related to constructing and maintaining a stable, democratic, and constitutionally based govern- ment in the newly independent Russian Federation. Russia recently adopted a constitution that expresses a dedication to the separation of powers doctrine.' Although this constitution represents a significant step forward in the transition from command economy and one-party rule to market economy and democratic rule, serious violations of the accepted separation of powers doctrine exist. A thorough evaluation of these violations, and indeed, the entire governmental structure of the Russian Federation is necessary to assess its chances for a successful and peace- ful transition and to suggest alternative means for achieving this goal. -

Separation of Powers: a Primer

7/6/2015 www.washingtontimes.com/news/2015/jul/5/celebratelibertymonthseparationofpowersapri/print/ You are currently viewing the printable version of this article, to return to the normal page, please click here. Separation of powers: A primer By Ryan J. Watson and James M. Burnham - - Sunday, July 5, 2015 Constitutional concepts like free speech or the right to bear arms are ingrained in our popular culture, but just 36% of Americans can name all three branches of the federal government.1 Even fewer understand why and how our Constitution allocates power among the Legislative, Executive, and Judicial branches. As we celebrate Liberty Month, it is worthwhile to review how the Constitution's separation of powers supplies a key bulwark protecting individual liberty in the world's most successful Republic. The Founders were familiar with human nature and the correlative tendency of every ruler towards tyranny. They had experienced oppression at the hands of the English King and realized that the only way to truly protect individual liberty was to limit the power of any single government official. James Madison, a central architect of the Constitution, rightly observed that if "men were angels, no government would be necessary." Federalist No. 51 (1788). He knew that every official or body would seek to accumulate "all powers, legislative, executive, and judiciary, in the same hands," and that such a concentration would be "the very definition of tyranny." Federalist No. 47 (1788). Thomas Jefferson agreed, labeling such a concentration of power as "precisely the definition of despotic government." Notes on the State of Virginia, Query 13 (1784). -

What Was the Iroquois Confederacy?

04 AB6 Ch 4.11 4/2/08 11:22 AM Page 82 What was the 4 Iroquois Confederacy? Chapter Focus Questions •What was the social structure of Iroquois society? •What opportunities did people have to participate in decision making? •What were the ideas behind the government of the Iroquois Confederacy? The last chapter explored the government of ancient Athens. This chapter explores another government with deep roots in history: the Iroquois Confederacy. The Iroquois Confederacy formed hundreds of years ago in North America — long before Europeans first arrived here. The structure and principles of its government influenced the government that the United States eventually established. The Confederacy united five, and later six, separate nations. It had clear rules and procedures for making decisions through representatives and consensus. It reflected respect for diversity and a belief in the equality of people. Pause The image on the side of this page represents the Iroquois Confederacy and its five original member nations. It is a symbol as old as the Confederacy itself. Why do you think this symbol is still honoured in Iroquois society? 82 04 AB6 Ch 4.11 4/2/08 11:22 AM Page 83 What are we learning in this chapter? Iroquois versus Haudenosaunee This chapter explores the social structure of Iroquois There are two names for society, which showed particular respect for women and the Iroquois people today: for people of other cultures. Iroquois (ear-o-kwa) and Haudenosaunee It also explores the structure and processes of Iroquois (how-den-o-show-nee). government. Think back to Chapter 3, where you saw how Iroquois is a name that the social structure of ancient Athens determined the way dates from the fur trade people participated in its government. -

Splitting Sovereignty: the Legislative Power and the Constitution's Federation of Independent States

Splitting Sovereignty: The Legislative Power and the Constitution's Federation of Independent States JAMES T. KNIGHT II* ABSTRACT From the moment the Constitutional Convention of 1787 ended and the Framers presented their plan to ªform a more perfect Union,º people have debated what form of government that union established. Had the thirteen sepa- rate states surrendered their independence to form a new state stretching from New England to Georgia, or was their individual sovereignty preserved as in the Articles of Confederation? If the states remained sovereign in some respect, what did that mean for the new national government? I propose that the original Constitution would have been viewed as establish- ing a federation of independent, sovereign states. The new federation possessed certain limited powers delegated to it by the states, but it lacked a broad power to legislate for the general welfare and the protection of individual rights. This power, termed ªthe legislative powerº by Enlightenment thinkers, was viewed as the essential, identifying power of a sovereign state under the theoretical framework of eighteenth-century political philosophy. The state constitutions adopted prior to the national Constitutional Convention universally gave their governments this broad legislative power rather than enumerate speci®c areas where the government could legislate. Of the constitutional documents adopted prior to the federal Constitution, only the Articles of Confederation provides such an enumeration. In this note, I argue that, against the background of political theory and con- stitutional precedent, a government lacking the full legislative power would not have been viewed as sovereign in its own right. -

The 2017 ITUC Global Rights Index the WORLD's WORST

THE WORLD'S WORST COUNTRIES FOR WORKERS The 2017 ITUC Global Rights Index | 4 The International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) is a confederation of national trade union centres, each of which links trade unions of that particular country. It was established on 1 November 2006, bringing together the organisations which were formerly affiliated to the ICFTU and WCL (both now dissolved) as well as a number of national trade union centres which had no international affiliation at the time. The new Confederation has 340 affiliated organisations in 163 countries and territories on all five continents, with a membership of 181 million, 40 per cent of whom are women. It is also a partner in “Global Unions” together with the Trade Union Advisory Committee to the OECD and the Global Union Federations (GUFs) which link together national unions from a particular trade or industry at international level. The ITUC has specialised offices in a number of countries around the world, and has General Consultative Status with the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations. The 2017 ITUC Global Rights Index | 6 Foreword .............................................9 ASIA .................................................. 70 Bangladesh ....................................... 71 Part I ..................................................13 Cambodia .......................................... 71 The 2017 Results ...............................14 China ................................................ 72 The ITUC Global Rights Index ...............19 Fiji -

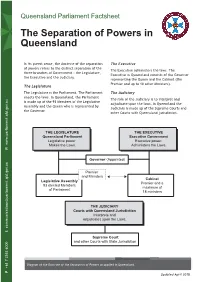

The Separation of Powers in Queensland

Queensland Parliament Factsheet The Separation of Powers in Queensland In its purest sense, the doctrine of the separation The Executive of powers refers to the distinct separation of the The Executive administers the laws. The three branches of Government - the Legislature, Executive in Queensland consists of the Governor the Executive and the Judiciary. representing the Queen and the Cabinet (the Premier and up to 18 other Ministers). The Legislature The Legislature is the Parliament. The Parliament The Judiciary enacts the laws. In Queensland, the Parliament The role of the Judiciary is to interpret and is made up of the 93 Members of the Legislative adjudicate upon the laws. In Queensland the Assembly and the Queen who is represented by Judiciary is made up of the Supreme Courts and the Governor. other Courts with Queensland jurisdiction. T ST T T Queensland Parliaent eutie oernent eislatie er ecutie er www.parliament.qld.gov.au aes the as dministers the as W Goernor inted Premier and inisters Cainet Leislatie ssel Premier and a elected emers maimum Parliament ministers T ourts with Queensland urisdition nterrets and adudicates un the as E [email protected] E [email protected] Supree ourt and ther urts ith tate urisdictin Diagram of the Doctrine of the Separation of Powers as applied in Queensland. +61 7 3553 6000 P Updated April 2018 Queensland Parliament Factsheet The Separation of Powers in Queensland Theoretically, each branch of government must be separate and not encroach upon the functions of the other branches. Furthermore, the persons who comprise these three branches must be kept separate and distinct. -

Another Word on the President's Statutory Authority Over Agency Action

ANOTHER WORD ON THE PRESIDENT’S STATUTORY AUTHORITY OVER AGENCY ACTION Nina A. Mendelson* By delegating to the “Secretary” or the “Administrator,” has Congress indicated an intent regarding presidential control of executive branch agencies? This seemingly simple interpretive question has prompted significant scholarly debate.1 In particular, if the statute names an executive branch agency head as actor, can the President be understood to possess so-called “directive” authority? “Directive” authority might be understood to cover the following situation: the President tells the agency head, “You have prepared materials indicating that options A, B, and C each satisfies statutory constraints and could be considered justified on the agency record. The Administration’s choice will be Option A.” The President could, of course, offer a reason— perhaps Option A is the least paternalistic, most protective, or most innovation-stimulating of the three. If the option preferred by the President otherwise complies with substantive statutory requirements on the record prepared by the agency,2 the question is whether the statutory reference to “Administrator” or “Secretary” should be understood as a limit on the President’s authority to direct the executive branch agency official to act in a particular way. A number of scholars have argued that statutory delegation to an executive branch agency official means that “the President cannot simply * Professor of Law, University of Michigan Law School. Thanks for valuable discussion and comments especially to Kevin Stack, as well as to Philip Harter, Riyaz Kanji, Sallyanne Payton, Peter Strauss, and participants in symposia at Fordham Law School and Cardozo Law School. -

The Ancient Constitution Vs. the Federalist Empire: Anti- Federalism from the Attack on "Monarchism" to Modern Localism

Copyright 1990 by Northwestern University, School of Law Printed in U.S.A. Northwestern University Law Review Vol. 84, No. I THE ANCIENT CONSTITUTION VS. THE FEDERALIST EMPIRE: ANTI- FEDERALISM FROM THE ATTACK ON "MONARCHISM" TO MODERN LOCALISM Carol M. Rose* Anti-Federalism is generally thought to represent a major "road not taken" in our political history. The Anti-Federalists, after all, lost the great debate in 1787-88, while their opponents' constitution prevailed and prospered over the years. If we needed proof of the staggering vic- tory of the Federalist Constitutional project, the 200th anniversary cele- brations of 1987 would certainly seem to have given it, at least insofar as victory is measured by longevity and adulation.' One of the most imposing signals of the Federalists' triumph is the manner in which their constitution has come to dominate the very rheto- ric of constitutionalism. This is particularly the case in the United States, where the federal Constitution has the status of what might be called the "plain vanilla" brand-a brand so familiar that it is assumed to be correct for every occasion. This Constitution is the standard by which we understand and judge other constitutions, as for example those of states and localities. 2 Indeed, the federal Constitution's rhetorical dominance extends to some degree even to other parts of the world, when foreign citizens look to it for guidance about their own governmental 3 structures. What, then, might be left over for the defeated Anti-Federalists? This Article is an effort to reconsider the degree to which the Anti-Feder- alist road may still be trod after all, and in particular to reconstruct some * Professor of Law, Yale University.