Structuring the Separation of Powers Philip B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requir

Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Economics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Gérard Roland, Chair Professor Ernesto Dal Bó Associate Professor Fred Finan Associate Professor Yuriy Gorodnichenko Spring 2018 Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences Copyright 2018 by Weijia Li 1 Abstract Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li Doctor of Philosophy in Economics University of California, Berkeley Professor Gérard Roland, Chair This dissertation explores how to solve incentive problems in autocracies through institu- tional arrangements centered around political meritocracy. The question is fundamental, as merit-based rewards and promotion of politicians are the cornerstones of key authoritarian regimes such as China. Yet the grave dilemmas in bureaucratic governance are also well recognized. The three essays of the dissertation elaborate on the various solutions to these dilemmas, as well as problems associated with these solutions. Methodologically, the disser- tation utilizes a combination of economic modeling, original data collection, and empirical analysis. The first chapter investigates the puzzle why entrepreneurs invest actively in many autoc- racies where unconstrained politicians may heavily expropriate the entrepreneurs. With a game-theoretical model, I investigate how to constrain politicians through rotation of local politicians and meritocratic evaluation of politicians based on economic growth. The key finding is that, although rotation or merit-based evaluation alone actually makes the holdup problem even worse, it is exactly their combination that can form a credible constraint on politicians to solve the hold-up problem and thus encourages private investment. -

Guidance Note

Guidance note The Crown Estate – Escheat All general enquiries regarding escheat should be Burges Salmon LLP represents The Crown Estate in relation addressed in the first instance to property which may be subject to escheat to the Crown by email to escheat.queries@ under common law. This note is a brief explanation of this burges-salmon.com or by complex and arcane aspect of our legal system intended post to Escheats, Burges for the guidance of persons who may be affected by or Salmon LLP, One Glass Wharf, interested in such property. It is not a complete exposition Bristol BS2 0ZX. of the law nor a substitute for legal advice. Basic principles English land law has, since feudal times, vested in the joint tenants upon a trust determine the bankrupt’s interest and been based on a system of tenure. A of land. the trustee’s obligations and liabilities freeholder is not an absolute owner but • Freehold property held subject to a trust. with effect from the date of disclaimer. a“tenant in fee simple” holding, in most The property may then become subject Properties which may be subject to escheat cases, directly from the Sovereign, as lord to escheat. within England, Wales and Northern Ireland paramount of all the land in the realm. fall to be dealt with by Burges Salmon LLP • Disclaimer by liquidator Whenever a “tenancy in fee simple”comes on behalf of The Crown Estate, except for In the case of a company which is being to an end, for whatever reason, the land in properties within the County of Cornwall wound up in England and Wales, the liquidator may, by giving the prescribed question may become subject to escheat or the County Palatine of Lancaster. -

LIS-133: Antigua and Barbuda: Archipelagic and Other Maritime

United States Department of State Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs Limits in the Seas No. 133 Antigua and Barbuda: Archipelagic and other Maritime Claims and Boundaries LIMITS IN THE SEAS No. 133 ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA ARCHIPELAGIC AND OTHER MARITIME CLAIMS AND BOUNDARIES March 28, 2014 Office of Ocean and Polar Affairs Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs U.S. Department of State This study is one of a series issued by the Office of Ocean and Polar Affairs, Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs in the Department of State. The purpose of the series is to examine a coastal State’s maritime claims and/or boundaries and assess their consistency with international law. This study represents the views of the United States Government only on the specific matters discussed therein and does not necessarily reflect an acceptance of the limits claimed. This study, and earlier studies in this series, may be downloaded from http://www.state.gov/e/oes/ocns/opa/c16065.htm. Comments and questions should be emailed to [email protected]. Principal analysts for this study are Brian Melchior and Kevin Baumert. 1 Introduction This study analyzes the maritime claims and maritime boundaries of Antigua and Barbuda, including its archipelagic baseline claim. The Antigua and Barbuda Maritime Areas Act, 1982, Act Number 18 of August 17, 1982 (Annex 1 to this study), took effect September 1, 1982, and established a 12-nautical mile (nm) territorial sea, 24-nm contiguous zone and 200-nm exclusive economic zone (EEZ).1 Pursuant to Act No. -

20 Thomas Jefferson.Pdf

d WHAT WE THINK ABOUT WHEN WE THINK ABOUT THOMAS JEFFERSON Todd Estes Thomas Jefferson is America’s most protean historical figure. His meaning is ever-changing and ever-changeable. And in the years since his death in 1826, his symbolic legacy has varied greatly. Because he was literally present at the creation of the Declaration of Independence that is forever linked with him, so many elements of subsequent American life—good and bad—have always attached to Jefferson as well. For a quarter of a century—as an undergraduate, then a graduate student, and now as a professor of early American his- tory—I have grappled with understanding Jefferson. If I have a pretty good handle on the other prominent founders and can grasp the essence of Washington, Madison, Hamilton, Adams and others (even the famously opaque Franklin), I have never been able to say the same of Jefferson. But at least I am in good company. Jefferson biographer Merrill Peterson, who spent a scholarly lifetime devoted to studying him, noted that of his contemporaries Jefferson was “the hardest to sound to the depths of being,” and conceded, famously, “It is a mortifying confession but he remains for me, finally, an impenetrable man.” This in the preface to a thousand page biography! Pe- terson’s successor as Thomas Jefferson Foundation Professor at Mr. Jefferson’s University of Virginia, Peter S. Onuf, has noted the difficulty of knowing how to think about Jefferson 21 once we sift through the reams of evidence and confesses “as I always do when pressed, that I am ‘deeply conflicted.’”1 The more I read, learn, write, and teach about Jefferson, the more puzzled and conflicted I remain, too. -

A Critique of John Stuart Mill Chris Daly

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Honors Theses University Honors Program 5-2002 The Boundaries of Liberalism in a Global Era: A Critique of John Stuart Mill Chris Daly Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/uhp_theses Recommended Citation Daly, Chris, "The Boundaries of Liberalism in a Global Era: A Critique of John Stuart Mill" (2002). Honors Theses. Paper 131. This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the University Honors Program at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. r The Boundaries of Liberalism in a Global Era: A Critique of John Stuart Mill Chris Daly May 8, 2002 r ABSTRACT The following study exanunes three works of John Stuart Mill, On Liberty, Utilitarianism, and Three Essays on Religion, and their subsequent effects on liberalism. Comparing the notion on individual freedom espoused in On Liberty to the notion of the social welfare in Utilitarianism, this analysis posits that it is impossible for a political philosophy to have two ultimate ends. Thus, Mill's liberalism is inherently flawed. As this philosophy was the foundation of Mill's progressive vision for humanity that he discusses in his Three Essays on Religion, this vision becomes paradoxical as well. Contending that the neo-liberalist global economic order is the contemporary parallel for Mill's religion of humanity, this work further demonstrates how these philosophical flaws have spread to infect the core of globalization in the 21 st century as well as their implications for future international relations. -

Thomas Jefferson and the Ideology of Democratic Schooling

Thomas Jefferson and the Ideology of Democratic Schooling James Carpenter (Binghamton University) Abstract I challenge the traditional argument that Jefferson’s educational plans for Virginia were built on mod- ern democratic understandings. While containing some democratic features, especially for the founding decades, Jefferson’s concern was narrowly political, designed to ensure the survival of the new republic. The significance of this piece is to add to the more accurate portrayal of Jefferson’s impact on American institutions. Submit your own response to this article Submit online at democracyeducationjournal.org/home Read responses to this article online http://democracyeducationjournal.org/home/vol21/iss2/5 ew historical figures have undergone as much advocate of public education in the early United States” (p. 280). scrutiny in the last two decades as has Thomas Heslep (1969) has suggested that Jefferson provided “a general Jefferson. His relationship with Sally Hemings, his statement on education in republican, or democratic society” views on Native Americans, his expansionist ideology and his (p. 113), without distinguishing between the two. Others have opted suppressionF of individual liberties are just some of the areas of specifically to connect his ideas to being democratic. Williams Jefferson’s life and thinking that historians and others have reexam- (1967) argued that Jefferson’s impact on our schools is pronounced ined (Finkelman, 1995; Gordon- Reed, 1997; Kaplan, 1998). because “democracy and education are interdependent” and But his views on education have been unchallenged. While his therefore with “education being necessary to its [democracy’s] reputation as a founding father of the American republic has been success, a successful democracy must provide it” (p. -

Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: a Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation Amy J

American University International Law Review Volume 10 | Issue 4 Article 6 1995 Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: A Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation Amy J. Weisman Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Weisman, Amy J. "Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: A Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation." American University International Law Review 10, no. 4 (1995): 1365-1398. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SEPARATION OF POWERS IN POST- COMMUNIST GOVERNMENT: A CONSTITUTIONAL CASE STUDY OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION Amy J. Weisman* INTRODUCTION This comment explores the myriad of issues related to constructing and maintaining a stable, democratic, and constitutionally based govern- ment in the newly independent Russian Federation. Russia recently adopted a constitution that expresses a dedication to the separation of powers doctrine.' Although this constitution represents a significant step forward in the transition from command economy and one-party rule to market economy and democratic rule, serious violations of the accepted separation of powers doctrine exist. A thorough evaluation of these violations, and indeed, the entire governmental structure of the Russian Federation is necessary to assess its chances for a successful and peace- ful transition and to suggest alternative means for achieving this goal. -

John Stuart Mill's Evaluations of Poetry

JOHN STUART MILL'S EVALUATIONS OF POETRY AND THEIR INFLUENCE UPON HIS INTELLECTUAL DEVELOPMENT by MILLO RUNDLE THOMPSON SHAW B.A., University of British Columbia, 1949 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of English We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1971 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of ENGLISH The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada Date October 1970 i JOHN STUART MILL'S EVALUATIONS OF POETRY AND THEIR INFLUENCE UPON HIS INTELLECTUAL DEVELOPMENT ABSTRACT The education of John Stuart Mill was one of the most unusual ever planned or experienced. Beginning with his learning Greek at the age of three and con• tinuing without a break of any kind to the age of four• teen, it constituted an almost total control of Mill's every waking activity, with the important exception of his visit to France at fourteen, until his appoint• ment to the East India Company in 1823. It emphasized the "tabula rasa" theory, the effect of external cir• cumstances on the developing mind, Hartley's Associa- tionist theory, and the judicious use of the Utilitarian theories of the "pleasure-pain" principle. -

The Causes of the American Revolution

Page 50 Chapter 12 By What Right Thomas Hobbes John Locke n their struggle for freedom, the colonists raised some age-old questions: By what right does government rule? When may men break the law? I "Obedience to government," a Tory minister told his congregation, "is every man's duty." But the Reverend Jonathan Boucher was forced to preach his sermon with loaded pistols lying across his pulpit, and he fled to England in September 1775. Thomas Jefferson wrote in the Declaration of Independence that when people are governed "under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such a Government." Both Boucher and Jefferson spoke to the question of whether citizens owe obedience to government. In an age when kings held near absolute power, people were told that their kings ruled by divine right. Disobedience to the king was therefore disobedience to God. During the seventeenth century, however, the English beheaded one King (King Charles I in 1649) and drove another (King James II in 1688) out of England. Philosophers quickly developed theories of government other than the divine right of kings to justify these actions. In order to understand the sources of society's authority, philosophers tried to imagine what people were like before they were restrained by government, rules, or law. This theoretical condition was called the state of nature. In his portrait of the natural state, Jonathan Boucher adopted the opinions of a well- known English philosopher, Thomas Hobbes. Hobbes believed that humankind was basically evil and that the state of nature was therefore one of perpetual war and conflict. -

The Contradiction of Classical Liberalism and Libertarianism

The contradiction of classical liberalism and libertarianism blogs.lse.ac.uk/businessreview/2017/02/01/the-contradiction-of-classical-liberalism-and-libertarianism/ 2/1/2017 A standard assumption in policy analyses and political debates is that classical liberal or libertarian views represent a radical alternative to a progressive or egalitarian agenda. In the political arena, classical liberalism and libertarianism often inform the policy agenda of centre-right and far- right parties. They underpin laissez-faire policies and reject any redistributive action, including welfare state provisions and progressive taxation. This is motivated by a fundamental belief in the value of personal autonomy and protection from (unjustified) external interference, including from the state. It is difficult to overestimate the philosophical and political relevance of classical liberalism and libertarianism. President Trump’s proposal to repeal the “Affordable Care Act (Obamacare)”, for example, is clearly inspired by a libertarian philosophical outlook whereby “No person should be required to buy insurance unless he or she wants to” (Healthcare Reform to Make America Great Again ). More generally, in the last four decades the political consensus, and the spectrum of policy proposals and outcomes, has significantly moved in a less interventionist, more laissez faire direction. The centrality of classical liberal and libertarian views has been such that the historical period after the end of the 1970s – following the election of Margaret Thatcher in the UK and Ronald Reagan in the US – has come to be known as the “Neoliberal era”. Yet the very coherence of the classical liberal and libertarian view of society, and its consistency with the fundamental tenets of modern democracies, have been questioned. -

Life, Liberty, and . . .: Jefferson on Property Rights

Journal of Libertarian Studies Volume 18, no. 1 (Winter 2004), pp. 31–87 2004 Ludwig von Mises Institute www.mises.org LIFE, LIBERTY, AND . : JEFFERSON ON PROPERTY RIGHTS Luigi Marco Bassani* Property does not exist because there are laws, but laws exist because there is property.1 Surveys of libertarian-leaning individuals in America show that the intellectual champions they venerate the most are Thomas Jeffer- son and Ayn Rand.2 The author of the Declaration of Independence is an inspiring source for individuals longing for liberty all around the world, since he was a devotee of individual rights, freedom of choice, limited government, and, above all, the natural origin, and thus the inalienable character, of a personal right to property. However, such libertarian-leaning individuals might be surprised to learn that, in academic circles, Jefferson is depicted as a proto-soc- ialist, the advocate of simple majority rule, and a powerful enemy of the wicked “possessive individualism” that permeated the revolution- ary period and the early republic. *Department Giuridico-Politico, Università di Milano, Italy. This article was completed in the summer of 2003 during a fellowship at the International Center for Jefferson Studies, Monticello, Va. I gladly acknowl- edge financial support and help from such a fine institution. luigi.bassani@ unimi.it. 1Frédéric Bastiat, “Property and Law,” in Selected Essays on Political Econ- omy, trans. Seymour Cain, ed. George B. de Huszar (Irvington-on-Hudson, N.Y.: Foundation for Economic Education, 1964), p. 97. 2E.g., “The Liberty Poll,” Liberty 13, no. 2 (February 1999), p. 26: “The thinker who most influenced our respondents’ intellectual development was Ayn Rand. -

The Separation of Powers in Queensland

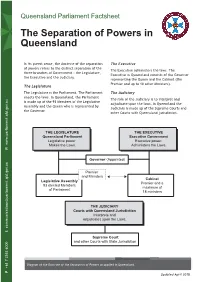

Queensland Parliament Factsheet The Separation of Powers in Queensland In its purest sense, the doctrine of the separation The Executive of powers refers to the distinct separation of the The Executive administers the laws. The three branches of Government - the Legislature, Executive in Queensland consists of the Governor the Executive and the Judiciary. representing the Queen and the Cabinet (the Premier and up to 18 other Ministers). The Legislature The Legislature is the Parliament. The Parliament The Judiciary enacts the laws. In Queensland, the Parliament The role of the Judiciary is to interpret and is made up of the 93 Members of the Legislative adjudicate upon the laws. In Queensland the Assembly and the Queen who is represented by Judiciary is made up of the Supreme Courts and the Governor. other Courts with Queensland jurisdiction. T ST T T Queensland Parliaent eutie oernent eislatie er ecutie er www.parliament.qld.gov.au aes the as dministers the as W Goernor inted Premier and inisters Cainet Leislatie ssel Premier and a elected emers maimum Parliament ministers T ourts with Queensland urisdition nterrets and adudicates un the as E [email protected] E [email protected] Supree ourt and ther urts ith tate urisdictin Diagram of the Doctrine of the Separation of Powers as applied in Queensland. +61 7 3553 6000 P Updated April 2018 Queensland Parliament Factsheet The Separation of Powers in Queensland Theoretically, each branch of government must be separate and not encroach upon the functions of the other branches. Furthermore, the persons who comprise these three branches must be kept separate and distinct.