Separation of Powers Doctrine As Applied to Cities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requir

Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Economics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Gérard Roland, Chair Professor Ernesto Dal Bó Associate Professor Fred Finan Associate Professor Yuriy Gorodnichenko Spring 2018 Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences Copyright 2018 by Weijia Li 1 Abstract Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li Doctor of Philosophy in Economics University of California, Berkeley Professor Gérard Roland, Chair This dissertation explores how to solve incentive problems in autocracies through institu- tional arrangements centered around political meritocracy. The question is fundamental, as merit-based rewards and promotion of politicians are the cornerstones of key authoritarian regimes such as China. Yet the grave dilemmas in bureaucratic governance are also well recognized. The three essays of the dissertation elaborate on the various solutions to these dilemmas, as well as problems associated with these solutions. Methodologically, the disser- tation utilizes a combination of economic modeling, original data collection, and empirical analysis. The first chapter investigates the puzzle why entrepreneurs invest actively in many autoc- racies where unconstrained politicians may heavily expropriate the entrepreneurs. With a game-theoretical model, I investigate how to constrain politicians through rotation of local politicians and meritocratic evaluation of politicians based on economic growth. The key finding is that, although rotation or merit-based evaluation alone actually makes the holdup problem even worse, it is exactly their combination that can form a credible constraint on politicians to solve the hold-up problem and thus encourages private investment. -

The Sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories in the Brexit Era

Island Studies Journal, 15(1), 2020, 151-168 The sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories in the Brexit era Maria Mut Bosque School of Law, Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, Spain MINECO DER 2017-86138, Ministry of Economic Affairs & Digital Transformation, Spain Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London, UK [email protected] (corresponding author) Abstract: This paper focuses on an analysis of the sovereignty of two territorial entities that have unique relations with the United Kingdom: the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories (BOTs). Each of these entities includes very different territories, with different legal statuses and varying forms of self-administration and constitutional linkages with the UK. However, they also share similarities and challenges that enable an analysis of these territories as a complete set. The incomplete sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and BOTs has entailed that all these territories (except Gibraltar) have not been allowed to participate in the 2016 Brexit referendum or in the withdrawal negotiations with the EU. Moreover, it is reasonable to assume that Brexit is not an exceptional situation. In the future there will be more and more relevant international issues for these territories which will remain outside of their direct control, but will have a direct impact on them. Thus, if no adjustments are made to their statuses, these territories will have to keep trusting that the UK will be able to represent their interests at the same level as its own interests. Keywords: Brexit, British Overseas Territories (BOTs), constitutional status, Crown Dependencies, sovereignty https://doi.org/10.24043/isj.114 • Received June 2019, accepted March 2020 © 2020—Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada. -

Local Government Primer

LOCAL GOVERNMENT PRIMER Alaska Municipal League Alaskan Local Government Primer Alaska Municipal League The Alaska Municipal League (AML) is a voluntary, Table of Contents nonprofit, nonpartisan, statewide organization of 163 cities, boroughs, and unified municipalities, Purpose of Primer............ Page 3 representing over 97 percent of Alaska's residents. Originally organized in 1950, the League of Alaska Cities............................Pages 4-5 Cities became the Alaska Municipal League in 1962 when boroughs joined the League. Boroughs......................Pages 6-9 The mission of the Alaska Municipal League is to: Senior Tax Exemption......Page 10 1. Represent the unified voice of Alaska's local Revenue Sharing.............Page 11 governments to successfully influence state and federal decision making. 2. Build consensus and partnerships to address Alaska's Challenges, and Important Local Government Facts: 3. Provide training and joint services to strengthen ♦ Mill rates are calculated by directing the Alaska's local governments. governing body to determine the budget requirements and identifying all revenue sources. Alaska Conference of Mayors After the budget amount is reduced by subtracting revenue sources, the residual is the amount ACoM is the parent organization of the Alaska Mu- required to be raised by the property tax.That nicipal League. The ACoM and AML work together amount is divided by the total assessed value and to form a municipal consensus on statewide and the result is identified as a “mill rate”. A “mill” is federal issues facing Alaskan local governments. 1/1000 of a dollar, so the mill rate simply states the amount of tax to be charged per $1,000 of The purpose of the Alaska Conference of Mayors assessed value. -

Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: a Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation Amy J

American University International Law Review Volume 10 | Issue 4 Article 6 1995 Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: A Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation Amy J. Weisman Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Weisman, Amy J. "Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: A Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation." American University International Law Review 10, no. 4 (1995): 1365-1398. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SEPARATION OF POWERS IN POST- COMMUNIST GOVERNMENT: A CONSTITUTIONAL CASE STUDY OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION Amy J. Weisman* INTRODUCTION This comment explores the myriad of issues related to constructing and maintaining a stable, democratic, and constitutionally based govern- ment in the newly independent Russian Federation. Russia recently adopted a constitution that expresses a dedication to the separation of powers doctrine.' Although this constitution represents a significant step forward in the transition from command economy and one-party rule to market economy and democratic rule, serious violations of the accepted separation of powers doctrine exist. A thorough evaluation of these violations, and indeed, the entire governmental structure of the Russian Federation is necessary to assess its chances for a successful and peace- ful transition and to suggest alternative means for achieving this goal. -

Taxes, Institutions, and Governance: Evidence from Colonial Nigeria

Taxes, Institutions and Local Governance: Evidence from a Natural Experiment in Colonial Nigeria Daniel Berger September 7, 2009 Abstract Can local colonial institutions continue to affect people's lives nearly 50 years after decolo- nization? Can meaningful differences in local institutions persist within a single set of national incentives? The literature on colonial legacies has largely focused on cross country comparisons between former French and British colonies, large-n cross sectional analysis using instrumental variables, or on case studies. I focus on the within-country governance effects of local insti- tutions to avoid the problems of endogeneity, missing variables, and unobserved heterogeneity common in the institutions literature. I show that different colonial tax institutions within Nigeria implemented by the British for reasons exogenous to local conditions led to different present day quality of governance. People living in areas where the colonial tax system required more bureaucratic capacity are much happier with their government, and receive more compe- tent government services, than people living in nearby areas where colonialism did not build bureaucratic capacity. Author's Note: I would like to thank David Laitin, Adam Przeworski, Shanker Satyanath and David Stasavage for their invaluable advice, as well as all the participants in the NYU predissertation seminar. All errors, of course, remain my own. Do local institutions matter? Can diverse local institutions persist within a single country or will they be driven to convergence? Do decisions about local government structure made by colonial governments a century ago matter today? This paper addresses these issues by looking at local institutions and local public goods provision in Nigeria. -

Reimagine Local Government

Reimagine Local Government English devolution: Chancellor aims for faster and more radical change English devolution: Chancellor aims for faster and more radical change • Experience of Greater Manchester has shown importance of Councils that have not yet signed up must be feeling pressure strong leadership to join the club, not least in Yorkshire, where so far only • Devolution in areas like criminal justice will help address Sheffield has done a deal with the government. complex social problems This is impressive progress for an initiative proceeding without • Making councils responsible for raising budgets locally a top-down legislative reorganisation and instead depends shows radical nature of changes on painstaking council-by-council negotiations. However, as all the combined authorities are acutely aware, the benefits • Cuts to business rates will stiffen the funding challenge, of devolution will not be realised unless they act swiftly and even for most dynamic councils decisively to turn words on paper into reality on the ground. With so much coverage of the Budget focusing on proposed Implementation has traditionally been a strength in local cuts to disability benefits, George Osborne’s changes to government. But until now implementation of new policies devolution and business rates rather flew under the radar. They has typically taken place within the boundaries of individual should not have done more attention. These reforms are likely local authorities. These devolution deals require a new set of to have lasting and dramatic impact on public services. skills – the ability to work across boundaries with neighbouring Osborne announced three new devolution deals – for East authorities and with other public bodies. -

Local Government Discretion and Accountability in Sierra Leone

Local Government Discretion and Accountability in Sierra Leone Benjamin Edwards, Serdar Yilmaz and Jamie Boex IDG Working Paper No. 2014-01 March 2014 Copyright © March 2014. The Urban Institute. Permission is granted for reproduction of this file, with attribution to the Urban Institute. The Urban Institute is a nonprofit, nonpartisan policy research and educational organization that examines the social, economic, and governance problems facing the nation. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Urban Institute, its trustees, or its funders. IDG Working Paper No. 2014-01 Local Government Discretion and Accountability in Sierra Leone Benjamin Edwards, Serdar Yilmaz and Jamie Boex March 2014 Abstract Sierra Leone is a small West African country with approximately 6 million people. Since 2002, the nation has made great progress in recovering from a decade-long civil war, in part due to consistent and widespread support for decentralization and equitable service delivery. Three rounds of peaceful elections have strengthened democratic norms, but more work is needed to cement decentralization reforms and strengthen local governments. This paper examines decentralization progress to date and suggests several next steps the government of Sierra Leone can take to overcome the remaining hurdles to full implementation of decentralization and improved local public service delivery. IDG Working Paper No. 2014-01 Local Government Discretion and Accountability in Sierra Leone Benjamin Edwards, Serdar Yilmaz and Jamie Boex 1. Introduction Sierra Leone is a small West African country with approximately 6 million people. Between 1991 and 2002 a brutal civil war infamous for its “blood diamonds” left thousands dead. -

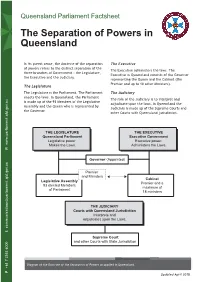

The Separation of Powers in Queensland

Queensland Parliament Factsheet The Separation of Powers in Queensland In its purest sense, the doctrine of the separation The Executive of powers refers to the distinct separation of the The Executive administers the laws. The three branches of Government - the Legislature, Executive in Queensland consists of the Governor the Executive and the Judiciary. representing the Queen and the Cabinet (the Premier and up to 18 other Ministers). The Legislature The Legislature is the Parliament. The Parliament The Judiciary enacts the laws. In Queensland, the Parliament The role of the Judiciary is to interpret and is made up of the 93 Members of the Legislative adjudicate upon the laws. In Queensland the Assembly and the Queen who is represented by Judiciary is made up of the Supreme Courts and the Governor. other Courts with Queensland jurisdiction. T ST T T Queensland Parliaent eutie oernent eislatie er ecutie er www.parliament.qld.gov.au aes the as dministers the as W Goernor inted Premier and inisters Cainet Leislatie ssel Premier and a elected emers maimum Parliament ministers T ourts with Queensland urisdition nterrets and adudicates un the as E [email protected] E [email protected] Supree ourt and ther urts ith tate urisdictin Diagram of the Doctrine of the Separation of Powers as applied in Queensland. +61 7 3553 6000 P Updated April 2018 Queensland Parliament Factsheet The Separation of Powers in Queensland Theoretically, each branch of government must be separate and not encroach upon the functions of the other branches. Furthermore, the persons who comprise these three branches must be kept separate and distinct. -

State Laws Governing Local Government Structure and Administration

Contents Chapter l-Local Governments in the United States ..................................................... 1 Types of Local Governments ...................................................................... 1 The Overall Pattern of Local Governments ......................................................... 3 TheReport ...................................................................................... 5 Chapter 2-Summary of Findings ...................................................................... 7 Key Developments from 1978 to 1990 ............................................................... 7 Conclusion ...................................................................................... 11 Appendices .......................................................................................... 15 A-Interpretation ofthe Tables .................................................................... 17 B-State Laws Governing Local Government Structurc and Administration: 1990 ....................... 19 C-How the State Laws Changed: 1978-1990 ........................................................ 57 D-Citations to State Constitutions and Statutes. .................................................... 91 E-Survey Questions for 1978 and 1990 ............................................................. 115 vii Special districts are the most numerous units of local airports, fire, natural resources, parks and recreation, and government. They are created either directly by state cemeteries, and districts with multiple functions). -

Local Levels in Federalism Constitutional Provisions and the State of Implementation

Local Levels in Federalism Constitutional Provisions and the State of Implementation Balananda Paudel Krishna Prasad Sapkota Local Levels in Federalism Constitutional Provisions and the State of Implementation Balananda Paudel Krishna Prasad Sapkota First published: July 2018 Publisher: Swatantra Nagarik Sanjal Nepal Maharajgunj, Kathmandu Background Democracy and Republicanism are popular ideas worldwide. These terms originated from the city-states of Athens and Rome in BCE 507, where directly elected democratic and republican governments were already in order. Even when autocratic and centralized governments were the global norm, local governments or entities were active in one form or another. Looking back at Nepali history, there are no documents available on the local governance system during the rule of the Gopalas and Ahirs. However, under the rule of the Kirants, Lichchhavis, and Mallas, local entities were found to be functioning effectively. Later, during the Shah/Rana dynasty also, local governments were functioning in one form or another. But it was not until much later in 1976 that it was realized that a government without people’s representatives could not be sustained, and Kathmandu Nagarpalika was formed, albeit under an autocratic national government. Slowly, other areas followed suit and local entities were established across different parts of the country. Even under the autocratic Panchayat system, there were attempts made to have elected local entities. The report of the Power Decentralisation Commission in 2020 BS (1963 CE), Decentralisation Act 2039 BS (1982 CE), the Man Mohan Adhikari government- initiated ‘Build your own village’ programme in 2051 BS (1995 CE), the report on decentralisation and local autonomy in 2053 BS (1996 CE), the Local Self- governance Act 2055 BS ((1999 CE), and the Decentralisation Implementation Plan 2055 BS (2001 CE) are notable for their experimentation, experience, and attempts at local autonomy. -

Separation of Powers and the Independence of Constitutional Courts and Equivalent Bodies

1 Christoph Grabenwarter Separation of Powers and the Independence of Constitutional Courts and Equivalent Bodies Keynote Speech 16 January 2011 2nd Congress of the World Conference on Constitutional Justice, Rio de Janeiro 1. Introduction Separation of Power is one of the basic structural principles of democratic societies. It was already discussed by ancient philosophers, deep analysis can be found in medieval political and philosophical scientific work, and we base our contemporary discussion on legal theory that has been developed in parallel to the emergence of democratic systems in Northern America and in Europe in the 18 th Century. Separation of Powers is not an end in itself, nor is it a simple tool for legal theorists or political scientists. It is a basic principle in every democratic society that serves other purposes such as freedom, legality of state acts – and independence of certain organs which exercise power delegated to them by a specific constitutional rule. When the organisers of this World Conference combine the concept of the separation of powers with the independence of constitutional courts, they address two different aspects. The first aspect has just been mentioned. The independence of constitutional courts is an objective of the separation of powers, independence is its result. This is the first aspect, and perhaps the aspect which first occurs to most of us. The second aspect deals with the reverse relationship: independence of constitutional courts as a precondition for the separation of powers. Independence enables constitutional courts to effectively control the respect for the separation of powers. As a keynote speech is not intended to provide a general report on the results of the national reports, I would like to take this opportunity to discuss certain questions raised in the national reports and to add some thoughts that are not covered by the questionnaire sent out a few months ago, but are still thoughts on the relationship between the constitutional principle and the independence of constitutional judges. -

Separation of Powers Between County Executive and County Fiscal Body

Separation of Powers Between County Executive and County Fiscal Body Karen Arland Ice Miller LLP September 27, 2017 Ice on Fire Separation of Powers Division of governmental authority into three branches – legislative, executive and judicial, each with specified duties on which neither of the other branches can encroach A constitutional doctrine of checks and balances designed to protect the people against tyranny 1 Ice on Fire Historical Background The phrase “separation of powers” is traditionally ascribed to French Enlightenment political philosopher Montesquieu, in The Spirit of the Laws, in 1748. Also known as “Montesquieu’s tri-partite system,” the theory was the division of political power between the executive, the legislature, and the judiciary as the best method to promote liberty. 2 Ice on Fire Constitution of the United States Article I – Legislative Section 1 – All legislative Powers granted herein shall be vested in a Congress of the United States. Article II – Executive Section 1 – The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America. Article III – Judicial The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish. 3 Ice on Fire Indiana Constitution of 1816 Article II - The powers of the Government of Indiana shall be divided into three distinct departments, and each of them be confided to a separate body of Magistracy, to wit: those which are Legislative to one, those which are Executive to another, and those which are Judiciary to another: And no person or collection of persons, being of one of those departments, shall exercise any power properly attached to either of the others, except in the instances herein expressly permitted.