Book Review Reconstructing the Administrative State in an Era of Economic and Democratic Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requir

Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Economics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Gérard Roland, Chair Professor Ernesto Dal Bó Associate Professor Fred Finan Associate Professor Yuriy Gorodnichenko Spring 2018 Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences Copyright 2018 by Weijia Li 1 Abstract Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li Doctor of Philosophy in Economics University of California, Berkeley Professor Gérard Roland, Chair This dissertation explores how to solve incentive problems in autocracies through institu- tional arrangements centered around political meritocracy. The question is fundamental, as merit-based rewards and promotion of politicians are the cornerstones of key authoritarian regimes such as China. Yet the grave dilemmas in bureaucratic governance are also well recognized. The three essays of the dissertation elaborate on the various solutions to these dilemmas, as well as problems associated with these solutions. Methodologically, the disser- tation utilizes a combination of economic modeling, original data collection, and empirical analysis. The first chapter investigates the puzzle why entrepreneurs invest actively in many autoc- racies where unconstrained politicians may heavily expropriate the entrepreneurs. With a game-theoretical model, I investigate how to constrain politicians through rotation of local politicians and meritocratic evaluation of politicians based on economic growth. The key finding is that, although rotation or merit-based evaluation alone actually makes the holdup problem even worse, it is exactly their combination that can form a credible constraint on politicians to solve the hold-up problem and thus encourages private investment. -

Intergovernmental Organizations and Foreign Policy Behavior: Some Empirical Findings James M

Political Science Publications Political Science 1979 Intergovernmental Organizations and Foreign Policy Behavior: Some Empirical Findings James M. McCormick Iowa State University, [email protected] Young W. Khil Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/pols_pubs Part of the American Politics Commons, Defense and Security Studies Commons, Other Political Science Commons, and the Policy Design, Analysis, and Evaluation Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ pols_pubs/28. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Political Science at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Political Science Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Intergovernmental Organizations and Foreign Policy Behavior: Some Empirical Findings Abstract In this study, we evaluate whether the increase in the number of intergovernmental organizations (IGOs) has resulted in their increased use for foreign policy behavior by the nations of the world. This question is examined in three related ways: (1) the aggregate use of IGOs for foreign policy behavior; (2) the relationship between IGO membership and IGO use; and (3) the kinds of states that use IGOs. Our data base consists of the 35 nations in the CREON (Comparative Research on the Events of Nations) data set for the years 1959-1968. The ainm findings are that IGOs were employed over 60 percent of the time with little fluctuation on a year- by-year basis, that global and "high politics" IGOs were used more often than regional and "low politics" IGOs, that institutional membership and IGO use were generally inversely related, and that the attributes of the states had limited utility in accounting for the use of intergovernmental organizations. -

Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: a Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation Amy J

American University International Law Review Volume 10 | Issue 4 Article 6 1995 Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: A Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation Amy J. Weisman Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Weisman, Amy J. "Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: A Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation." American University International Law Review 10, no. 4 (1995): 1365-1398. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SEPARATION OF POWERS IN POST- COMMUNIST GOVERNMENT: A CONSTITUTIONAL CASE STUDY OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION Amy J. Weisman* INTRODUCTION This comment explores the myriad of issues related to constructing and maintaining a stable, democratic, and constitutionally based govern- ment in the newly independent Russian Federation. Russia recently adopted a constitution that expresses a dedication to the separation of powers doctrine.' Although this constitution represents a significant step forward in the transition from command economy and one-party rule to market economy and democratic rule, serious violations of the accepted separation of powers doctrine exist. A thorough evaluation of these violations, and indeed, the entire governmental structure of the Russian Federation is necessary to assess its chances for a successful and peace- ful transition and to suggest alternative means for achieving this goal. -

Postmodern Imperialism and the European Union

Troyer I Postmodern Imperialism and the European Union An Honors Thesis (POLS 404) by Tanner Troyer Thesis Advisor Dr. E. Gene Frankland Ball State University Muncie, Indiana December 2011 Expected Date of Graduation December 2011 Troyer" Abstract Throughout history, dominant nations have exerted control over foreign parts of the world. In the past, powerful nations would colonize other parts of the world in order to expand their own reach . This practice was referred to as imperialism. Imperialism often involved direct violence, coercion, and subjugation of native populations. Colonial imperialism is a thing of the past. Despite this, dominant powers still exert their influence on other parts of the world. This is referred to as postmodern imperialism. The most common methods of postmodern imperialism involve the spread of capitalism and culture to other nations. Dominant powers such as the United States and European Union are involved with these practices. This paper will focus on the European Union and how its policies exert influence upon other nations in a manner consistent with postmodern imperialism. Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr. Gene Frankland for being my advisor for this project. Writing this paper was one of the hardest parts of my college career, and I would not have been able to do it without him. I would also like to thank David Hekel, James Robinson, and Alex Jung for the help and encouragement they gave during the making of this paper. Troyer III Outline I. Introduction A. What is imperialism? B. Why is it important? II. Literature Review - Imperialism of Today A. -

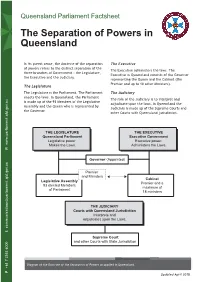

The Separation of Powers in Queensland

Queensland Parliament Factsheet The Separation of Powers in Queensland In its purest sense, the doctrine of the separation The Executive of powers refers to the distinct separation of the The Executive administers the laws. The three branches of Government - the Legislature, Executive in Queensland consists of the Governor the Executive and the Judiciary. representing the Queen and the Cabinet (the Premier and up to 18 other Ministers). The Legislature The Legislature is the Parliament. The Parliament The Judiciary enacts the laws. In Queensland, the Parliament The role of the Judiciary is to interpret and is made up of the 93 Members of the Legislative adjudicate upon the laws. In Queensland the Assembly and the Queen who is represented by Judiciary is made up of the Supreme Courts and the Governor. other Courts with Queensland jurisdiction. T ST T T Queensland Parliaent eutie oernent eislatie er ecutie er www.parliament.qld.gov.au aes the as dministers the as W Goernor inted Premier and inisters Cainet Leislatie ssel Premier and a elected emers maimum Parliament ministers T ourts with Queensland urisdition nterrets and adudicates un the as E [email protected] E [email protected] Supree ourt and ther urts ith tate urisdictin Diagram of the Doctrine of the Separation of Powers as applied in Queensland. +61 7 3553 6000 P Updated April 2018 Queensland Parliament Factsheet The Separation of Powers in Queensland Theoretically, each branch of government must be separate and not encroach upon the functions of the other branches. Furthermore, the persons who comprise these three branches must be kept separate and distinct. -

The High and Low Politics of Trade Can the World Trade Organization's

Global Agenda The High and Low Politics of Trade Can the World Trade Organization’s Centrality Be Restored in a New Multi-Tiered Global Trading System? August 2015 © WORLD ECONOMIC FORUM, 2015 – All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system. REF 170815 Contents 3 Preface 7 Introduction 8 Restoring WTO Centrality to a Multi-Tiered Global Trading System 8 GATT’s centricity in global trade governance 8 21st-century system diversity and erosion of WTO centricity 8 Mega-regionals and plurilaterals 9 The importance of keeping the WTO going 12 High Politics, the Current Interregnum and the Global Trading System 12 A historic transformation 12 The leadership challenge 12 New issues, negotiating approaches and divisions 14 Low Politics of International Trade and Investment 14 Industrial policy and the multilateral trading system 16 Special interests and the interplay among key states 18 Where High and Low Politics Meet: National Security and Cybersecurity 18 National security in the WTO 19 Cybersecurity 20 Some concluding observations 22 A Very Special Case: China’s Emerging Perspectives on the Global Trade Order 22 Key drivers of change in China’s trade policy 23 China’s emerging trade policy 23 Why will China embrace higher-standard FTAs? 24 The New Silk Road initiatives, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and China’s trade policy 25 Implications for the global trade order: back to the future? 26 Is an Inclusive Trading System Possible? Mega- Regionals and Beyond 26 Building blocks 26 Stumbling blocks 26 Crumbling blocks 27 Back to high politics 30 References 31 Endnotes Can the World Trade Organization’s Centrality Be Restored in a New Multi-Tiered Global Trading System? 3 4 The High and Low Politics of Trade Preface Sean Doherty Deeply intertwined, trade and investment shape economic growth, development and industry Head, competitiveness, affecting human welfare around the world. -

Health Diplomacy As a Soft Power Strategy Or Ethical Duty? Case Study: Brazil in the 21St Century

Health diplomacy as a soft power strategy or ethical duty? Case Study: Brazil in the 21st century Key words: Brazil, Health Diplomacy, Soft power, Cosmopolitanism, Foreign Policy Esmee S. Heijstek S1600591 [email protected] July 2015 MA International Relations, Leiden University Words: 9258 Supervisor: Dr. M.L. Wiesebron 1 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1. Health diplomacy as a form of soft power or as an ethical duty?............................. 5 Soft power ............................................................................................................................... 6 Ethical duty ............................................................................................................................. 9 Chapter 2. Brazil’s actions over time within the developing area of health diplomacy .......... 11 The emergence of health diplomacy ..................................................................................... 11 The World Health Organization and health diplomacy ........................................................ 12 New actors in the field of health diplomacy ......................................................................... 13 Health diplomacy in global and regional policy agendas ..................................................... 13 Chapter 3. Why improve the health of others through health diplomacy?............................... 16 South-South -

Separation of Powers and the Independence of Constitutional Courts and Equivalent Bodies

1 Christoph Grabenwarter Separation of Powers and the Independence of Constitutional Courts and Equivalent Bodies Keynote Speech 16 January 2011 2nd Congress of the World Conference on Constitutional Justice, Rio de Janeiro 1. Introduction Separation of Power is one of the basic structural principles of democratic societies. It was already discussed by ancient philosophers, deep analysis can be found in medieval political and philosophical scientific work, and we base our contemporary discussion on legal theory that has been developed in parallel to the emergence of democratic systems in Northern America and in Europe in the 18 th Century. Separation of Powers is not an end in itself, nor is it a simple tool for legal theorists or political scientists. It is a basic principle in every democratic society that serves other purposes such as freedom, legality of state acts – and independence of certain organs which exercise power delegated to them by a specific constitutional rule. When the organisers of this World Conference combine the concept of the separation of powers with the independence of constitutional courts, they address two different aspects. The first aspect has just been mentioned. The independence of constitutional courts is an objective of the separation of powers, independence is its result. This is the first aspect, and perhaps the aspect which first occurs to most of us. The second aspect deals with the reverse relationship: independence of constitutional courts as a precondition for the separation of powers. Independence enables constitutional courts to effectively control the respect for the separation of powers. As a keynote speech is not intended to provide a general report on the results of the national reports, I would like to take this opportunity to discuss certain questions raised in the national reports and to add some thoughts that are not covered by the questionnaire sent out a few months ago, but are still thoughts on the relationship between the constitutional principle and the independence of constitutional judges. -

Separation of Powers Between County Executive and County Fiscal Body

Separation of Powers Between County Executive and County Fiscal Body Karen Arland Ice Miller LLP September 27, 2017 Ice on Fire Separation of Powers Division of governmental authority into three branches – legislative, executive and judicial, each with specified duties on which neither of the other branches can encroach A constitutional doctrine of checks and balances designed to protect the people against tyranny 1 Ice on Fire Historical Background The phrase “separation of powers” is traditionally ascribed to French Enlightenment political philosopher Montesquieu, in The Spirit of the Laws, in 1748. Also known as “Montesquieu’s tri-partite system,” the theory was the division of political power between the executive, the legislature, and the judiciary as the best method to promote liberty. 2 Ice on Fire Constitution of the United States Article I – Legislative Section 1 – All legislative Powers granted herein shall be vested in a Congress of the United States. Article II – Executive Section 1 – The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America. Article III – Judicial The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish. 3 Ice on Fire Indiana Constitution of 1816 Article II - The powers of the Government of Indiana shall be divided into three distinct departments, and each of them be confided to a separate body of Magistracy, to wit: those which are Legislative to one, those which are Executive to another, and those which are Judiciary to another: And no person or collection of persons, being of one of those departments, shall exercise any power properly attached to either of the others, except in the instances herein expressly permitted. -

The Covid-19 Pandemic, Geopolitics, and International Law

journal of international humanitarian legal studies 11 (2020) 237-248 brill.com/ihls The covid-19 Pandemic, Geopolitics, and International Law David P Fidler Adjunct Senior Fellow, Council on Foreign Relations, USA [email protected] Abstract Balance-of-power politics have shaped how countries, especially the United States and China, have responded to the covid-19 pandemic. The manner in which geopolitics have influenced responses to this outbreak is unprecedented, and the impact has also been felt in the field of international law. This article surveys how geopolitical calcula- tions appeared in global health from the mid-nineteenth century through the end of the Cold War and why such calculations did not, during this period, fundamentally change international health cooperation or the international law used to address health issues. The astonishing changes in global health and international law on health that unfolded during the post-Cold War era happened in a context not characterized by geopolitical machinations. However, the covid-19 pandemic emerged after the bal- ance of power had returned to international relations, and rival great powers have turned this pandemic into a battleground in their competition for power and influence. Keywords balance of power – China – coronavirus – covid-19 – geopolitics – global health – International Health Regulations – international law – pandemic – United States – World Health Organization © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2020 | doi:10.1163/18781527-bja10010 <UN> 238 Fidler 1 Introduction A striking feature of the covid-19 pandemic is how balance-of-power politics have influenced responses to this outbreak.1 The rivalry between the United States and China has intensified because of the pandemic. -

Commanding a View: How “Expertise Forcing” Undermines the Unitary Executive and Statemanship in a Democratic Republic

Commanding a View: How “Expertise Forcing” Undermines the Unitary Executive and Statemanship in a Democratic Republic Daniel Shapiro CSAS Working Paper 21-28 WORKING DRAFT COMMANDING A VIEW How “Expertise Forcing” Undermines the Unitary Executive and Statesmanship in a Democratic Republic Daniel Shapiro When right, I shall often be thought wrong by those whose positions will not command a view of the whole ground.1 It is by comparing a variety of information, we are frequently enable[d] to investigate facts, which were so intricate or hidden, that no single clue could have led to the knowledge of them in this point of view, intelligence becomes interesting, which from but its connection & collateral circumstances, would not be important.2 INTRODUCTION: Political Control of the Bureaucracy Is political control over agency decisionmaking arbitrary and capricious?3 A line of thought in academia and on the bench has concluded that political or presidential influence over agency decisions violates the Administrative Procedure Act (APA). This position holds that most executive policy determinations must be made by technical experts based on empirical evidence. To survive this standard, decisions of the highest political impact—birth control,4 climate change,5 assisted suicide,6 wartime necessity7— must be made by expert 1 Jefferson’s First Inaugural Address, 33 Papers of Thomas Jefferson 134–52 (Barbara B. Oberg, ed. 2007) (Mar. 4, 1801). 2 George Washington to James Lovell (Apr. 1, 1782). 3 5 U.S.C. § 706. 4 Tummino v. Torti, 603 F. Supp. 2d 519, 545 (E.D.N.Y. 2009). 5 Massachusetts v. EPA, 549 U.S. -

The Separation of Powers Doctrine: an Overview of Its Rationale and Application

Order Code RL30249 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web The Separation of Powers Doctrine: An Overview of its Rationale and Application June 23, 1999 (name redacted) Legislative Attorney American Law Division Congressional Research Service The Library of Congress ABSTRACT This report discusses the philosophical underpinnings, constitutional provisions, and judicial application of the separation of powers doctrine. In the United States, the doctrine has evolved to entail the identification and division of three distinct governmental functions, which are to be exercised by separate branches of government, classified as legislative, executive, and judicial. The goal of this separation is to promote governmental efficiency and prevent the excessive accumulation of power by any single branch. This has been accomplished through a hybrid doctrine comprised of the separation of powers principle and the notion of checks and balances. This structure results in a governmental system which is independent in certain respects and interdependent in others. The Separation of Powers Doctrine: An Overview of its Rationale and Application Summary As delineated in the Constitution, the separation of powers doctrine represents the belief that government consists of three basic and distinct functions, each of which must be exercised by a different branch of government, so as to avoid the arbitrary exercise of power by any single ruling body. This concept was directly espoused in the writings of Montesquieu, who declared that “when the executive