In Favor of Meritocracy, Not Against Democracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Managing Meritocracy in Clientelistic Democracies∗

Managing Meritocracy in Clientelistic Democracies∗ Sarah Brierleyy Washington University in St Louis May 8, 2018 Abstract Competitive recruitment for certain public-sector positions can co-exist with partisan hiring for others. Menial positions are valuable for sustaining party machines. Manipulating profes- sional positions, on the other hand, can undermine the functioning of the state. Accordingly, politicians will interfere in hiring partisans to menial position but select professional bureau- crats on meritocratic criteria. I test my argument using novel bureaucrat-level data from Ghana (N=18,778) and leverage an exogenous change in the governing party to investigate hiring pat- terns. The results suggest that partisan bias is confined to menial jobs. The findings shed light on the mixed findings regarding the effect of electoral competition on patronage; competition may dissuade politicians from interfering in hiring to top-rank positions while encouraging them to recruit partisans to lower-ranked positions [123 words]. ∗I thank Brian Crisp, Stefano Fiorin, Barbara Geddes, Mai Hassan, George Ofosu, Dan Posner, Margit Tavits, Mike Thies and Daniel Triesman, as well as participants at the African Studies Association Annual Conference (2017) for their comments. I also thank Gangyi Sun for excellent research assistance. yAssistant Professor, Department of Political Science, Washington University in St. Louis. Email: [email protected]. 1 Whether civil servants are hired by merit or on partisan criteria has broad implications for state capacity and the overall health of democracy (O’Dwyer, 2006; Grzymala-Busse, 2007; Geddes, 1994). When politicians exchange jobs with partisans, then these jobs may not be essential to the running of the state. -

Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requir

Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Economics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Gérard Roland, Chair Professor Ernesto Dal Bó Associate Professor Fred Finan Associate Professor Yuriy Gorodnichenko Spring 2018 Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences Copyright 2018 by Weijia Li 1 Abstract Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li Doctor of Philosophy in Economics University of California, Berkeley Professor Gérard Roland, Chair This dissertation explores how to solve incentive problems in autocracies through institu- tional arrangements centered around political meritocracy. The question is fundamental, as merit-based rewards and promotion of politicians are the cornerstones of key authoritarian regimes such as China. Yet the grave dilemmas in bureaucratic governance are also well recognized. The three essays of the dissertation elaborate on the various solutions to these dilemmas, as well as problems associated with these solutions. Methodologically, the disser- tation utilizes a combination of economic modeling, original data collection, and empirical analysis. The first chapter investigates the puzzle why entrepreneurs invest actively in many autoc- racies where unconstrained politicians may heavily expropriate the entrepreneurs. With a game-theoretical model, I investigate how to constrain politicians through rotation of local politicians and meritocratic evaluation of politicians based on economic growth. The key finding is that, although rotation or merit-based evaluation alone actually makes the holdup problem even worse, it is exactly their combination that can form a credible constraint on politicians to solve the hold-up problem and thus encourages private investment. -

TESTING the SCHOLARS How Do You Choose Who Runs a Dynasty? Why Do People Seek Power?

TESTING THE SCHOLARS How do you choose who runs a dynasty? Why do people seek power? ACTIVITY DESCRIPTION Students will explore the classical Chinese civil servants exam system, compare it to / EDUCATOR their current exam systems, and construct their own ideas of what it means to be qualified for a role and how to prove qualification. If you are planning to use this as part of a visit to The Field Museum, see the Page field trip guide on page 7. 1 of BACKGROUND 7 INFORMATION Image: During the Qing Dynasty, students took the civil service examination in door-less cells. Running an empire required a network of The only furniture was a set of boards that could be arranged as a desk and bench or a bed. dedicated and well-educated officials. The men Illustration by Sayaka Isowa for The Field Museum. who governed the empire had to pass a grueling exam. For roughly 1,300 years, China’s emperors used the civil toe, twice. Their supplies, carried in baskets like service examination system to identify talented men for the ones in the drawing above, were searched. It’s government service. Stationed throughout the empire, said that guards even checked inside dumplings. scholar-officials maintained order and reported back to Yet some test-takers found ways to smuggle in help. the emperor on local events. This system was so effective, The museum holds examples of silk cloth covered in even foreign dynasties like the Manchus embraced it writing, cheat sheets that could have been sewn into during the Qing Dynasty (AD 1644-1911). -

Meritocracy: a Widespread Ideology Due to School Socialization? Marie Duru-Bellat, Elise Tenret

Meritocracy: A widespread ideology due to school socialization? Marie Duru-Bellat, Elise Tenret To cite this version: Marie Duru-Bellat, Elise Tenret. Meritocracy: A widespread ideology due to school socialization?. 2010. hal-00972712 HAL Id: hal-00972712 https://hal-sciencespo.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00972712 Preprint submitted on 3 Apr 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Meritocracy: A Widespread Ideology Due to School Socialization? Marie Duru-Bellat et Elise Tenret Notes & Documents n° 2010-02 Juillet 2010 Résumé : La recherche présentée dans ce papier se centre sur la perception de la méritocratie et sur l’adhésion à la méritocratie scolaire. En la matière, on explore précisément l’influence de l’éducation à la fois au niveau micro (individuel) et au niveau macro (pays), dans la mesure où l’éducation, selon Bourdieu et Passeron (1970) est censée affecter l’adhésion aux idéologies dominantes. Cependant, ces chercheurs n’en apportent pas de preuve empirique. De plus, l’influence de l’éducation n’est pas univoque, car elle peut avoir des effets contradictoires sur la justification des inégalités sociales (Baer et Lambert 1982), et aussi parce que ces effets peuvent être différents selon le niveau d’analyse (individus ou pays). -

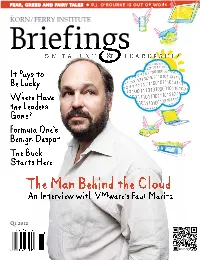

The Man Behind the Cloud an Interview with Vmware’S Paul Maritz

fear, greed and fairy tales • p.j. o’rourke is out off wworkrk It Pays to Be Lucky Where Have the Leaders Gone? Formula One’s Benign Despot The Buck Starts Here The Man Behind the Cloud An Interview with VMware’s Paul Maritz Q1.2012.2012 chief executive officer Gary Burnison chief marketing officer Michael Distefano editor-in-chief Joel Kurtzman creative director Joannah Ralston circulation director Peter Pearsall marketing operations manager Reonna Johnson board of advisors Sergio Averbach Cheryl Buxton Joe Griesedieck Byrne Mulrooney Kristen Badgley Dennis Carey Robert Hallagan Indranil Roy Michael Bekins Bob Damon Katie Lahey Jane Stevenson Stephen Bruyant-Langer Ana Dutra Robert McNabb Anthony Vardy contributing editors Chris Bergonzi Stephanie Mitchell David Berreby P.J. O’Rourke Lawrence M. Fisher Glenn Rifkin Victoria Griffi th Adrian Wooldridge Cover photo of Paul Maritz: The Korn/Ferry International Briefi ngs on Talent and Leadership is published Jeff Singer quarterly by the Korn/Ferry Institute. The Korn/Ferry Institute was founded to serve Cover illustration: as a premier global voice on a range of talent management and leadership issues. The Zé Otavio Institute commissions, originates and publishes groundbreaking research utilizing Korn/ Ferry’s unparalleled expertise in executive recruitment and talent development combined with its preeminent behavioral research library. The Institute is dedicated to improving the state of global human capital for businesses of all sizes around the world. ISSN 1949-8365 Copyright 2012, Korn/Ferry International Requests for additional copies should be sent directly to: Briefi ngs Magazine 1900 Avenue of the Stars, Suite 2600, Los Angeles, CA 90067 briefi [email protected] Briefi ngs is produced with solar power, FSC-certifi ed Advertising Sales Representative: paper, and soy-based inks, Erica Springer + Associates, LLC in a fully sustainable and 1355 S. -

Between Political Meritocracy and Participatory Democracy: Toward Realist Confucian Democracy

Culture and Dialogue 8 (2020) 251-279 brill.com/cad Between Political Meritocracy and Participatory Democracy: Toward Realist Confucian Democracy Darren Yutang Jin Hertford College, Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK [email protected] Abstract In this article, I examine the textual underpinnings of participatory Confucian democ- racy and Confucian meritocracy and propose realist Confucian democracy as an alter- native following a balanced reading of classic Confucianism. I argue that Confucian plebeian values do not square with the political meritocrats’ (Daniel A. Bell and Tongdong Bai) advocacy for meritocratic rule while Confucian elitist values undermine participatory democrats’ (Sor-hoon Tan and Stephen Angle) ardor for justifications of active democratic participation. A shared difficulty with both groups is that they tend to overuse one aspect of Confucianism while leaving the status of other elements in limbo. The discussion of participatory democracy and meritocracy is followed by the introduction of an eclectic reading that strikes a dynamic balance between elitist and plebeian values in Confucianism, and which points to the wide gamut of realist de- mocracy that combines democratic election with strong leadership. Keywords participatory Confucian democracy – Confucian meritocracy – realist Confucian democracy – classic Confucianism – Confucian political theory – political realism 1 Introduction Recent focus on the relationship between Confucianism and democracy has shifted away from examining their mere compatibility to discussing possibilities © Darren Yutang Jin, 2020 | doi:10.1163/24683949-12340086 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY 4.0Downloaded license. from Brill.com09/27/2021 01:35:19AM via free access 252 Jin of “Confucian democracy” and “Confucian meritocracy” that build on the intellectual strength of both traditions. -

Meritocratic Elitism, Authoritarian Libertarianism, and the Limits of the China Model Or: What Are We Talking About When We Talk About Alternatives?

SYMPOSIUM THE CHINA MODEL MERITOCRATIC ELITISM, AUTHORITARIAN LIBERTARIANISM, AND THE LIMITS OF THE CHINA MODEL OR: WHAT ARE WE TALKING ABOUT WHEN WE TALK ABOUT ALTERNATIVES? BY PEITAO JIA © 2017 ² Philosophy and Public Issues (New Series), Vol. 7, No. 1 (2017): 105-126 Luiss University Press E-ISSN 2240-7987 | P-ISSN 1591-0660 [THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK] THE CHINA MODEL Meritocratic Elitism, Authoritarian Libertarianism, and the Limits of The China Model Or: What are We Talking about When We Talk about Alternatives? Peitao Jia n this article, as a review and critique of the current theorization and defense of political meritocracy (PM), I I examine what the factual political issues demand and what the theory of PM has promised and provided. By arguing that PM leads to meritocratic elitism that neglects individual citizens· civil and political rights as well as authoritarian libertarianism that undermines the people·s economic, social, and cultural welfare, I shall conclude this discussion with remarks that political meritocracy cannot be a desirable alternative to liberal democracy and on the contrary it requires its own alternatives based on liberal and egalitarian values. As one of the most important contemporary theorists of political meritocracy, Daniel A. Bell defends this selection-and- promotion system as an ´alternative modelµ to liberal democracy (LD) in his well-argued book The China Model: Political Meritocracy and the Limits of Democracy.1 1 Daniel A. Bell, The China Model: Political Meritocracy and the Limits of Democracy (Princeton: Princeton University Press 2015), p. 4. © 2017 ² Philosophy and Public Issues (New Series), Vol. -

The 03Rd Century This Is the Century of the Military Showdown

86 3. The State The 03rd Century This is the century of the military showdown. In the east, Ch! M"!n-wa!ng, who ruled from 0300, was eager for conquest. After long delay for preparation, a delay which the Gwa"ndz" theorists urgently advised, he attacked Su# ng in 0285. And conquered it, but allied states drove him from Su# ng and from Ch! itself. He died far from his capital in 0284, and Ch! never again ranked as a major power. Its eclipse favored its western rival: Ch!n. Lord Sha$ng or We#! Ya$ng, a general of Ch!n, had defeated Ngwe#! in 0342; he was given the fief of Sha$ng and a ministership in 0341. His reputation in other states was military, but Ch!n tradition (found in the Sha$ng-jyw$nShu$) claimed him as a statesman, and it is possible that he applied military discipline (harsh punishments, no exemptions for nobles) to the civilian population also. As in Ch!, reward and punishment are the root axioms of 03c Ch!n legal theory: 3:72 (SJS 9:2a, excerpt, c0295). Now, the nature of men is to like titles and salaries and to hate punishments and penalties. A ruler institutes these two things to control men’s wills . But in contrast to eastern thought, the SJS firmly rejects antiquity arguments: 3:73 (SJS 7:2c, excerpt, c0288). The Sage neither imitates the ancient nor cultivatesthemodern...theThreeDynastieshaddifferentsituations,but they all managed to rule. Thus, to rise to the Kingship, there is one way, but to hold it, there are different principles. -

A Critical Discussion of Daniel A. Bell's Political Meritocracy

Journal of chinese humanities 4 (2�18) 6-28 brill.com/joch A Critical Discussion of Daniel A. Bell’s Political Meritocracy Huang Yushun 黃玉順 Professor of philosophy, Shandong University, China [email protected] Translated by Kathryn Henderson Abstract “Meritocracy” is among the political phenomena and political orientations found in modern Western democratic systems. Daniel A. Bell, however, imposes it on ancient Confucianism and contemporary China and refers to it in Chinese using loaded terms such as xianneng zhengzhi 賢能政治 and shangxian zhi 尚賢制. Bell’s “politi- cal meritocracy” not only consists of an anti-democratic political program but also is full of logical contradictions: at times, it is the antithesis of democracy, and, at other times, it is a supplement to democracy; sometimes it resolutely rejects democracy, and sometimes it desperately needs democratic mechanisms as the ultimate guar- antee of its legitimacy. Bell’s criticism of democracy consists of untenable platitudes, and his defense of “political meritocracy” comprises a series of specious arguments. Ultimately, the main issue with “political meritocracy” is its blatant negation of popu- lar sovereignty as well as the fact that it inherently represents a road leading directly to totalitarianism. Keywords Democracy – meritocracy – political meritocracy – totalitarianism It is rather surprising that, in recent years, Daniel A. Bell’s views on “political meritocracy” have been selling well in China. In addition, the Chinese edi- tion of his most recent and representative work, The China Model: Political © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2018 | doi:10.1163/23521341-12340055Downloaded from Brill.com09/23/2021 12:26:47PM via free access A Critical Discussion of Daniel A. -

“On Meritocracy and Equality” Daniel Bell Distilled by Sandra Yu

“On meritocracy and equality” Daniel Bell Distilled by Sandra Yu Daniel Bell takes a liberal stance in tackling the populist cry for equality and its objections to meritocracy. The main issue is that of meritocracy versus equality. There are two crucially different types of equality that must be considered: that of opportunity and that of result. Meritocracy is compatible with equal opportunity, but inevitably leads to unequal result. Therefore, Bell’s question for the populists is whether they want genuine equal opportunity or equal result. In the past, equal opportunity was desirable. However, the replacement of value of thought by that of sentiment, coupled with the realization that equal environments do not necessarily produce equal income, wealth or status led to the demand for a society that provided equal results. Bell believes that the populist objections to meritocracy—inherited intelligence, inherited social connections, the random influence of luck, too much competition and inequality through equal opportunity—both contradict each other and overlap. Bell claims that if equal result is to be the driving force that forms social policy, there must be sound ethical justification. He acknowledges that there has been an effort to establish a philosophical argument for a communal society (as opposed to one that favors individuals), namely the idea of justice as fairness. Bell examines Rousseau, Mill and Rawls’s defenses of equal result, and decides that group rights contradictable individual rights, which are the fundamental tenet of traditional liberalism. Therefore, he claims that their arguments are inadequate. In the end, Bell rejects the call for equality of result, claiming that inequality is both inevitable and acceptable. -

The Moral Basis of Political Meritocracy

SYMPOSIUM THE CHINA MODEL THE MORAL BASIS OF POLITICAL MERITOCRACY BY ELENA ZILIOTTI © 2017 ² Philosophy and Public Issues (New Series), Vol. 7, No. 1 (2017): 246-270 Luiss University Press E-ISSN 2240-7987 | P-ISSN 1591-0660 [THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK] THE CHINA MODEL The Moral Basis of Political Meritocracy Elena Zilliotti olitical meritocracy is the view that members of the legislative branch must be chosen and promoted on the P basis of their individual skills, character and performance. Democratic and meritocratic theories differ from one another not in the types of political agencies that they support, but in the governmental body to which meritocratic selection criteria apply. Several democratic theories require selecting the members of the judiciary branch through meritocratic mechanisms, but only meritocratic theories allow for the extension of meritocratic selection principles to the composition of the legislature.1 In practice, political meritocracy is compatible with democratic institutions in various ways. Recently, Daniel A. Bell has argued 1 For a defense of meritocratic selection systems outside the legislative branch, VHH 6WHSKHQ 0DFHGR·V FRQVWLWXWLRQDO WKHRU\ RI GHPRFUDF\ ZKHUH MXGLFLDU\ review and regulatory agencies are insulated from direct electoral DFFRXQWDELOLWLHV 6WHSKHQ 0DFHGR ´Meritocratic Democracy: Learning from WKH$PHULFDQ&RQVWLWXWLRQµ in Bell D. and Li C. (eds.), The East Asian Challenge for Democracy: Political Meritocracy in Comparative Perspective, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013, 232î256). Also Philip Pettit claims that a democratic system of a large modern society requires establishing meritocratic agencies WR UHVROYH PDWWHUV LQ WKH VSHFLILF GRPDLQV LQ ZKLFK SHRSOH·V SUHIHUHQFHVDUHTXLWHFOHDU 3KLOLS3HWWLW´0HULWRFUDWLF5HSUHVHQWDWLRQµ%HOO' and Li C. -

The Limits of Political Meritocracy: Screening Mayors in China Under Imperfect Verifiability

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES THE LIMITS OF POLITICAL MERITOCRACY: SCREENING MAYORS IN CHINA UNDER IMPERFECT VERIFIABILITY Juan Carlos Suárez Serrato Xiao Yu Wang Shuang Zhang Working Paper 21963 http://www.nber.org/papers/w21963 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 February 2016 We thank Douglas Almond, Kehinde Ajayi, Attila Ambrus, Abhijit Banerjee, Pat Bayer, Charlie Becker, Prashant Bharadwaj, Allan Collard-Wexler, Julie Cullen, Esther Duflo, Pascaline Dupas, Erica Field, Fred Finan, Rob Garlick, Gopi Goda, Cynthia Kinnan, David Lam, Danielle Li, Hugh Macartney, Matt Masten, Michael Powell, Nancy Qian, Orie Shelef, Erik Snowberg, Duncan Thomas, Chris Udry, Daniel Xu, Xiaoxue Zhao, and participants in the NBER/BREAD Fall Development Meetings, the Duke Labor/Development Seminar, the Colegio de Mexico seminar, the 2015 World Congress of the Econometric Society, the 2015 Society for the Advancement of Economic Theory, and NEUDC Brown for helpful comments. This paper was previously circulated under the title “The One Child Policy and Promotion of Mayors in China.” Suárez Serrato and Zhang thank the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR) for financial support. Suárez Serrato gratefully acknowledges support from the Kauffman Foundation. We thank Pawel Charasz, Stephanie Karol, Han Gao, Matt Panhans, and Victor Ye for providing excellent research assistance. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications.