Prose Works of Jonathan Swift

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shakespeare in Geneva

Shakespeare in Geneva SHAKESPEARE IN GENEVA Early Modern English Books (1475-1700) at the Martin Bodmer Foundation Lukas Erne & Devani Singh isbn 978-2-916120-90-4 Dépôt légal, 1re édition : janvier 2018 Les Éditions d’Ithaque © 2018 the bodmer Lab/université de Genève Faculté des lettres - rue De-Candolle 5 - 1211 Genève 4 bodmerlab.unige.ch TABLE OF CONTENts Acknowledgements 7 List of Abbreviations 8 List of Illustrations 9 Preface 11 INTRODUctION 15 1. The Martin Bodmer Foundation: History and Scope of Its Collection 17 2. The Bodmer Collection of Early Modern English Books (1475-1700): A List 31 3. The History of Bodmer’s Shakespeare(s) 43 The Early Shakespeare Collection 43 The Acquisition of the Rosenbach Collection (1951-52) 46 Bodmer on Shakespeare 51 The Kraus Sales (1970-71) and Beyond 57 4. The Makeup of the Shakespeare Collection 61 The Folios 62 The First Folio (1623) 62 The Second Folio (1632) 68 The Third Folio (1663/4) 69 The Fourth Folio (1685) 71 The Quarto Playbooks 72 An Overview 72 Copies of Substantive and Partly Substantive Editions 76 Copies of Reprint Editions 95 Other Books: Shakespeare and His Contemporaries 102 The Poetry Books 102 Pseudo-Shakespeare 105 Restoration Quarto Editions of Shakespeare’s Plays 106 Restoration Adaptations of Plays by Shakespeare 110 Shakespeare’s Contemporaries 111 5. Other Early Modern English Books 117 NOTE ON THE CATALOGUE 129 THE CATALOGUE 135 APPENDIX BOOKS AND MANUscRIPts NOT INCLUDED IN THE CATALOGUE 275 Works Cited 283 Acknowledgements We have received precious help in the course of our labours, and it is a pleasure to acknowl- edge it. -

Pdf\Preparatory\Charles Wesley Book Catalogue Pub.Wpd

Proceedings of the Charles Wesley Society 14 (2010): 73–103. (This .pdf version reproduces pagination of printed form) Charles Wesley’s Personal Library, ca. 1765 Randy L. Maddox John Wesley made a regular practice of recording in his diary the books that he was reading, which has been a significant resource for scholars in considering influences on his thought.1 If Charles Wesley kept such diary records, they have been lost to us. However, he provides another resource among his surviving manuscript materials that helps significantly in this regard. On at least four occasions Charles compiled manuscript catalogues of books that he owned, providing a fairly complete sense of his personal library around the year 1765. Indeed, these lists give us better records for Charles Wesley’s personal library than we have for the library of brother John.2 The earliest of Charles Wesley’s catalogues is found in MS Richmond Tracts.3 While this list is undated, several of the manuscript hymns that Wesley included in the volume focus on 1746, providing a likely time that he started compiling the list. Changes in the color of ink and size of pen make clear that this was a “growing” list, with additions being made into the early 1750s. The other three catalogues are grouped together in an untitled manuscript notebook containing an assortment of financial records and other materials related to Charles Wesley and his family.4 The first of these three lists is titled “Catalogue of Books, 1 Jan 1757.”5 Like the earlier list, this date indicates when the initial entries were made; both the publication date of some books on the list and Wesley’s inscriptions in surviving volumes make clear that he continued to add to the list over the next few years. -

Reworkings in the Textual History of Gulliver's Travels: a Translational

Reworkings in the textual history of Gulliver’s Travels: a translational approach Alice Colombo The thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Portsmouth August 2013 ii ABSTRACT On 28 October 1726 Gulliver’s Travels debuted on the literary scene as a political and philosophical satire meant to provoke and entertain an audience of relatively educated and wealthy British readers. Since then, Swift’s work has gradually evolved, assuming multiple forms and meanings while becoming accessible and attractive to an increasingly broad readership in and outside Britain. My study emphasises that reworkings, including re-editions, translations, abridgments, adaptations and illustrations, have played a primary role in this process. Its principal aim is to investigate how reworkings contributed to the popularity of Gulliver’s Travels by examining the dynamics and the stages through which they transformed its text and its original significance. Central to my research is the assumption that this transformation is largely the result of shifts of a translational nature and that, therefore, the analysis of reworkings and the understanding of their role can greatly benefit from the models of translation description devised in Descriptive Translation Studies. The reading of reworkings as entailing processes of translation shows how derivative creations operate collaboratively to ensure literary works’ continuous visibility and actively shape the literary polysystem. The study opens with an exploration of existing approaches to reworkings followed by an examination of the characteristics which exposed Gulliver’s Travels to continuous rethinking and reworking. Emphasis is put on how the work’s satirical significance gave rise to a complex early textual problem for which Gulliver’s Travels can be said to have debuted on the literary scene as a derivative production in the first place. -

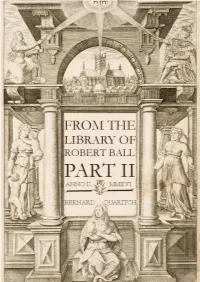

The Library of Robert Ball: Part Ii

BERNARD QUARITCH LTD. 40 SOUTH AUDLEY ST, LONDON W1K 2PR Tel: +44 (0)20-7297 4888 Fax: +44 (0)20-7297 4866 e-mail: [email protected] web site: www.quaritch.com Bankers: Barclays Bank plc, 50 Pall Mall, P.O. Box 15162, London SW1A 1QB Sort code: 20-65-82 Swift code: BARCGB22 Sterling account: IBAN: GB98 BARC 206582 10511722 Euro account: IBAN: GB30 BARC 206582 45447011 U.S. Dollar account: IBAN: GB46 BARC 206582 63992444 VAT number: GB 840 1358 54 MasterCard, Visa, and American Express accepted Recent Catalogues: 1433 English Books and Manuscripts 1432 Continental Books 1431 Travel & Exploration, Natural History Recent Lists: 2016/1 Human Sciences 2015/9 Early Drama 2015/8 Flora and Fauna 2015/7 Classics 2015/6 Design and Interiors 2015/5 Library of Robert Ball, Part I List 2016/2 Cover image from item 57. © Bernard Quaritch 2016 FROM THE LIBRARY OF ROBERT BALL: PART II English Literature 1500-1900, an American Journalist’s Collection Collecting rare books is a selfish pastime. It is about possession, about ownership. After all, the texts are universally available. Even the books themselves are often accessible in public libraries. But that is not the same as having them in one’s own bookcase. I have been an active collector for most of a long life. Now, in my 90th year, I have decided it is time to pass my pleasure on to others. Robert Ball 1) AUBREY, John. Miscellanies, viz. I. Day-Fatality. II. Local-Fatality. III. Ostenta. IV. Omens. V. Dreams. VI. Apparitions. VII. Voices. -

Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels

Bloom’s Modern Critical Interpretations The Adventures of The Grapes of Wrath Portnoy’s Complaint Huckleberry Finn Great Expectations A Portrait of the Artist The Age of Innocence The Great Gatsby as a Young Man Alice’s Adventures in Gulliver’s Travels Pride and Prejudice Wonderland The Handmaid’s Tale Ragtime All Quiet on the Heart of Darkness The Red Badge of Western Front I Know Why the Courage As You Like It Caged Bird Sings The Rime of the The Ballad of the Sad The Iliad Ancient Mariner Café Jane Eyre The Rubáiyát of Omar Beowulf The Joy Luck Club Khayyám Black Boy The Jungle The Scarlet Letter The Bluest Eye Lord of the Flies Silas Marner The Canterbury Tales The Lord of the Rings Song of Solomon Cat on a Hot Tin Love in the Time of The Sound and the Roof Cholera Fury The Catcher in the The Man Without The Stranger Rye Qualities A Streetcar Named Catch-22 The Metamorphosis Desire The Chronicles of Miss Lonelyhearts Sula Narnia Moby-Dick The Tale of Genji The Color Purple My Ántonia A Tale of Two Cities Crime and Native Son The Tempest Punishment Night Their Eyes Were The Crucible 1984 Watching God Darkness at Noon The Odyssey Things Fall Apart Death of a Salesman Oedipus Rex To Kill a Mockingbird The Death of Artemio The Old Man and the Ulysses Cruz Sea Waiting for Godot Don Quixote On the Road The Waste Land Emerson’s Essays One Flew Over the White Noise Emma Cuckoo’s Nest Wuthering Heights Fahrenheit 451 One Hundred Years of Young Goodman A Farewell to Arms Solitude Brown Frankenstein Persuasion Bloom’s Modern Critical Interpretations Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels New Edition Edited and with an introduction by Harold Bloom Sterling Professor of the Humanities Yale University Bloom’s Modern Critical Interpretations: Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels— New Edition Copyright ©2009 by Infobase Publishing Introduction ©2009 by Harold Bloom All rights reserved. -

Peter Harrington Catalogue 70

www.peterharringtonbooks.com Peter Harrington Catalogue 70 Early Printed Books • Economics & Politics • History Law • Medicine • Philosophy • Science Peter Harrington Catalogue 70 Early Printed Books • Economics & Politics • History Law • Medicine • Philosophy • Science Section One: We are next exhibiting at these international book fairs: Featured Items 1 ~ 14 New York Antiquarian Book Fair 9–11 April 2010 The Park Avenue Armory, 643 Park Avenue at 67th St., New York, NY Booth D31 Section Two: Main Catalogue Items 15 ~ 177 www.abaa.org Paris International Antiquarian Book Fair 16–18 April 2010 Grand Palais, Paris Stand D12 www.salondulivreancienparis.fr London, 53rd Antiquarian Book Fair 3–5 June 2010 Olympia 2, Hammersmith, London Stand 72 www.olympiabookfair.com Our new website with extra features: www.peterharringtonbooks.com ! Fully secure checkout We accept all major credit cards, as well as direct Shop Opening Hours: ! Easy to use, with advanced search function payment to: Monday to Saturday, 10.00 - 18.00 Acc. Name: Peter Harrington ! Browse by subject, with over 100 categories to choose from Peter Harrington Account Number:40010920 ! View multiple images with high-resolution zoom 100 Fulham Road, Chelsea, London SW3 6HS Sort Code: 82-60-22 Read our print catalogues in fully interactive format Tel.+44 (0)20 7591 0220 ! IBAN number GB73CLYD82602240010920 Fax +44 (0)20 7225 7054 ! Create an account, and shop safely and easily with one-click ordering BIC/SWIFT code: CLYDGB21022 email: [email protected] ! Create a personalised wish list Bank: Clydesdale Bank, 2 Bishop’s Wharf, ! Free shipping on orders placed through the website Walnut Tree Close, Guildford, GU1 4UP. -

Swift, the Book, and the Irish Financial Revolution Moore, Sean D

Swift, the Book, and the Irish Financial Revolution Moore, Sean D. Published by Johns Hopkins University Press Moore, Sean D. Swift, the Book, and the Irish Financial Revolution: Satire and Sovereignty in Colonial Ireland. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.475. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/475 [ Access provided at 28 Sep 2021 16:55 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Swift, the Book, and the Irish Financial Revolution This page intentionally left blank Swift, the Book, and the Irish Financial Revolution Satire and Sovereignty in Colonial Ireland Sean D. MooRe The Johns Hopkins University Press Baltimore © 2010 The Johns Hopkins University Press all rights reserved. Published 2010 Printed in the United States of america on acid-free paper 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 The Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 north Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Moore, Sean D. Swift, the book, and the Irish financial revolution : satire and sovereignty in Colonial Ireland / Sean Moore. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBn-13: 978-0-8018-9507-4 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBn-10: 0-8018-9507-3 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Swift, Jonathan, 1667–1745—Criticism and interpretation. 2. Satire, english—History and criticism. 3. english literature—Irish authors—History and criticism. 4. national characteristics, Irish. 5. Ireland—History—autonomy and independence movements. 6. Ireland—economic conditions. -

Universidade Federal De Santa Catarina Centro De Comunicação E Expressão Departamento De Línguas E Literaturas Estrangeiras

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SANTA CATARINA CENTRO DE COMUNICAÇÃO E EXPRESSÃO DEPARTAMENTO DE LÍNGUAS E LITERATURAS ESTRANGEIRAS Richard F.S. Costa THE CONSTRUING OF ALLUSIONS IN AN UNABRIDGED TRANSLATION OF GULLIVER’S TRAVELS Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso Florianópolis 2013 Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso submetido ao Departamento de Línguas e Literaturas Estrangeiras do Centro de Comunicação e Expressão na Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Bacharel em Letras – Língua Inglesa e Literaturas. Banca Examinadora: __________________________________ Prof. Dr. Markus Johannes Weininger Orientador __________________________________ Prof. Dr. José Roberto O‘Shea Abstract This is a partial critical analysis of an unabridged translation, to Brazilian Portuguese, of Jonathan Swift‘s Gulliver’s Travels, with a specific focus on its use and elucidation of allusions as an aid for reading comprehension. This was achieved by exploring research on literary allusions and the translation of allusions, and applying these theoretical views to the examination of both English-language scholars of the source text and the translator‘s own commentaries on the translated text. It has been found that minimum change with some measure of guidance is the best method to construe allusions in translation. The use of allusions in Gulliver’s Travels is complex and intricate, but a rich heritage of commentary and historical views are able to render the allusions clearer to a present-day reader. Keywords: translation, allusion, Jonathan Swift, reading comprehension. Word count: 11.566 Resumo Esta é uma análise crítica parcial de uma tradução integral, ao português brasileiro, das Viagens de Gulliver de Jonathan Swift, com uma ênfase específica em seu uso e elucidação de alusões como uma ferramenta para compreensão de leitura. -

A Comparative Analysis of Paratextual Elements in the Complete Translations of Gulliver’S Travels

Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of Translation and Interpreting A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF PARATEXTUAL ELEMENTS IN THE COMPLETE TRANSLATIONS OF GULLIVER’S TRAVELS Esra Duygu ÖZDOĞAN Master’s Thesis Ankara, 2018 A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF PARATEXTUAL ELEMENTS IN THE COMPLETE TRANSLATIONS OF GULLIVER’S TRAVELS Esra Duygu ÖZDOĞAN Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of Translation and Interpreting Master’s Thesis Ankara, 2018 v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Asst. Prof. Dr. Elif ERSÖZLÜ for her valuable supports and contributions throughout the entire period of my study. Her deep sincerity and valuable feedbacks have made it possible to finish this thesis. I feel lucky to have the chance of being her student. I also would like to express my sincere thanks to the members of the thesis committee, Prof. Dr. Asalet ERTEN and Assoc. Prof. Dr. Aslı Özlem TARAKÇIOĞLU for their contributions and invaluable comments. I am also deeply grateful to Prof. Dr. Can Ömer KALAYCI who has made time for me and has accepted my request of an interview. He has supplied significant information for my thesis. I would like to thank my close friends Tuğçe Mermer and Ece Janset Yağmur for their endless support and motivation. Their smiling faces and sincerity have motivated me throughout the writing process of this study. Last but not least, I am deeply grateful to my parents Müjgan Özdoğan and Faruk Özdoğan for their love and understanding, and to my aunt Münevver Aşık who put her faith in me and supported me in all conditions. -

Browse Pdf Catalog

1 FOR THE COLLECTION OF A LIFETIME The process of creating one’s personal library is the pursuit of a lifetime. It requires special thought and consideration. Each book represents a piece of history, and it is a remarkable task to assemble these individual items into a collection. Our aim at Raptis Rare Books is to render tailored, individualized service to help you achieve your goals. We specialize in working with private collectors with a specific wish list, helping individuals find the ideal gift for special occasions, and partnering with representatives of institutions. We are here to assist you in your pursuit. Thank you for letting us be your guide in bringing the library of your imagination to reality. OUR GUARANTEE All items are fully guaranteed and can be returned within ten days. We accept all major credit cards and offer a wide range of shipping options. Each purchase is expertly packaged to ensure safe arrival and free gift wrapping services are available upon request. There are few gifts that are as lasting and appreciated as a rare book. FOR MORE INFORMATION For further details regarding any of the items featured in these pages, visit our website or call 561-508-3479 for expert assistance from one of our booksellers. Raptis Rare Books | 226 Worth Avenue | Palm Beach, Florida 33480 561-508-3479 | [email protected] www.RaptisRareBooks.com Contents Ancient History, Philosophy & Religion...........................................................2 Travel & Exploration............................................................................................8 -

Rose Mark Authors and Owne

M.C. Sloss Collection Authors and Owners Authors and Owners The Invention of Copyright Mark Rose Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England Copyright 1993 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Second printing, 1994 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rose, Mark. Authors and owners : the invention of copyright / Mark Rose. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-674-05308-7 (alk. paper) (cloth) ISBN 0-674-05309-5 (pbk.) i. Copyright Great Britain History. 2. Copyright United States History. I. Title. KDi300.R67 1993 346.4i04'82 dcao [344-106482] 92-43010 CIP For Ted Preface My interest in copyright emerges from my experience as a literary "expert witness" in a number of copyright-infringement cases. The principal cases in which I have participated a suit against a television police serial with a science-fictional gimmick (one of the cops was a robot), a suit against a made-for-television movie about a child "genius" and his experiences in college, a suit against Raiders of the Lost Ark by the author of a long, mystical novel about the Ark of the Covenant, a suit against a movie about the rock music industry in the 19505, a suit against a television movie about an alien invader are, I believe, rep- resentative of run-of-the-mill infringement cases in the film and tele- vision industry. The issues are usually access and similarity. Did the defendant have access to the plaintiff's work, and could he or she have copied that work or otherwise taken something of value from it? Is the defendant's work so similar to the plaintiff's that plagiarism is a rea- sonable hypothesis, or, alternatively, is the defendant's work different enough from the plaintiff's to be considered original? The issue for the expert witness is usually similarity. -

Swift Studies, 22 (2007) (Last Updated June 2018)

THE HOLDINGS OF THE EHRENPREIS CENTRE: A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF RARE BOOKS Swift Studies, 22 (2007) (Last updated June 2018) SWIFT, JONATHAN COLLECTED WORKS The Works of J. S, D. D, D. S. P. D. in Four Volumes. Dublin: George Faulkner, 1735. ROTHSCHILD 2151; TEERINK AND SCOUTEN 41. The Works of J. S, D. D, D. S. P. D. Vols 3-6 (Dublin: George Faulkner, 1738). TEERINK AND SCOUTEN 50. The Works of J. S, D. D, D. S. P. D. in Six Volumes. Dublin: George Faulkner, 1738. TEERINK AND SCOUTEN 42. Volume II is dated 1737. The Works of J. S. D. D. D. S. P. D. in Six Volumes. Dublin: George Faulkner, 1742- TEERINK AND SCOUTEN 43. The Works of Jonathan Swift, D. D, D. S. P. D. in Eight Volumes. 11 vols (Dublin: George Faulkner, 1746). TEERINK AND SCOUTEN 44 and 45A. The Works of Dr. Jonathan Swift, Dean of St. Patrick’s Dublin: Accurately Corrected by the Best Editions. 9 vols (Dublin: G. and A. Ewing, 1758). TEERINK AND SCOUTEN 98. The Works of the Reverend Dr. Jonathan Swift, Dean of St. Patrick’s, Dublin: With an Account of his Life and Writings. 11 vols (Dublin: George Faulkner, 1762). TEERINK AND SCOUTEN 53. The Works of the Reverend Dr. Jonathan Swift, D. S. P. D. in Eleven Volumes. 16 vols (Dublin: George Faulkner, 1763-67), with volumes 12 and 13 “collected and revised by Deane Swift” (1765) and volumes 14-16 “with Notes Explanatory and Historical” by Thomas Birch, John Hawkesworth, and Thomas Wilkes (1767). 1 Volumes 2, 3, 4, 5 (Dublin: George Faulkner, 1737, 1738, 1760, 1759) are from other sets.