Language at Work in Jonathan Swift

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary Ingo Gildenhard https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Ingo Gildenhard The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the author(s), but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work. Attribution should include the following information: Ingo Gildenhard, Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119. Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018. https://doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0156 Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/845#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www. -

Shakespeare in Geneva

Shakespeare in Geneva SHAKESPEARE IN GENEVA Early Modern English Books (1475-1700) at the Martin Bodmer Foundation Lukas Erne & Devani Singh isbn 978-2-916120-90-4 Dépôt légal, 1re édition : janvier 2018 Les Éditions d’Ithaque © 2018 the bodmer Lab/université de Genève Faculté des lettres - rue De-Candolle 5 - 1211 Genève 4 bodmerlab.unige.ch TABLE OF CONTENts Acknowledgements 7 List of Abbreviations 8 List of Illustrations 9 Preface 11 INTRODUctION 15 1. The Martin Bodmer Foundation: History and Scope of Its Collection 17 2. The Bodmer Collection of Early Modern English Books (1475-1700): A List 31 3. The History of Bodmer’s Shakespeare(s) 43 The Early Shakespeare Collection 43 The Acquisition of the Rosenbach Collection (1951-52) 46 Bodmer on Shakespeare 51 The Kraus Sales (1970-71) and Beyond 57 4. The Makeup of the Shakespeare Collection 61 The Folios 62 The First Folio (1623) 62 The Second Folio (1632) 68 The Third Folio (1663/4) 69 The Fourth Folio (1685) 71 The Quarto Playbooks 72 An Overview 72 Copies of Substantive and Partly Substantive Editions 76 Copies of Reprint Editions 95 Other Books: Shakespeare and His Contemporaries 102 The Poetry Books 102 Pseudo-Shakespeare 105 Restoration Quarto Editions of Shakespeare’s Plays 106 Restoration Adaptations of Plays by Shakespeare 110 Shakespeare’s Contemporaries 111 5. Other Early Modern English Books 117 NOTE ON THE CATALOGUE 129 THE CATALOGUE 135 APPENDIX BOOKS AND MANUscRIPts NOT INCLUDED IN THE CATALOGUE 275 Works Cited 283 Acknowledgements We have received precious help in the course of our labours, and it is a pleasure to acknowl- edge it. -

Pdf\Preparatory\Charles Wesley Book Catalogue Pub.Wpd

Proceedings of the Charles Wesley Society 14 (2010): 73–103. (This .pdf version reproduces pagination of printed form) Charles Wesley’s Personal Library, ca. 1765 Randy L. Maddox John Wesley made a regular practice of recording in his diary the books that he was reading, which has been a significant resource for scholars in considering influences on his thought.1 If Charles Wesley kept such diary records, they have been lost to us. However, he provides another resource among his surviving manuscript materials that helps significantly in this regard. On at least four occasions Charles compiled manuscript catalogues of books that he owned, providing a fairly complete sense of his personal library around the year 1765. Indeed, these lists give us better records for Charles Wesley’s personal library than we have for the library of brother John.2 The earliest of Charles Wesley’s catalogues is found in MS Richmond Tracts.3 While this list is undated, several of the manuscript hymns that Wesley included in the volume focus on 1746, providing a likely time that he started compiling the list. Changes in the color of ink and size of pen make clear that this was a “growing” list, with additions being made into the early 1750s. The other three catalogues are grouped together in an untitled manuscript notebook containing an assortment of financial records and other materials related to Charles Wesley and his family.4 The first of these three lists is titled “Catalogue of Books, 1 Jan 1757.”5 Like the earlier list, this date indicates when the initial entries were made; both the publication date of some books on the list and Wesley’s inscriptions in surviving volumes make clear that he continued to add to the list over the next few years. -

Letter from the Chair Symposium Committee

Letter from the Chair Welcome to the Life, the Universe, & Everything Sym- statement I’ve ever made, but I stand by it. Over the posium on Science Fiction and Fantasy, or as we affec- next three days I advise you to do two things: learn tionately call it, LTUE. If you’re here for the first, tenth, everything you can and have an amazing time doing it. or the thirty-fourth time (or any number of years in- I’ve frequently been told by our attendees how much between), I sincerely hope you’ll find this weekend to be LTUE means to them. Between gushing about amaz- not just enjoyable but sensational. ing experiences with our panelists, as well as with other I’d like to start out by thanking each and every one of attendees, they often reference some sort of energy that you for being here. Whether you’re here as an attendee, LTUE seems to give them. This energy inspires them to a presenter, or a volunteer, your presence is incredibly get up and create something. This year the committee important to the LTUE experience. While the sympo- has poured countless hours of energy into this year’s pro- sium as an idea will always exist, without people who gramming, and I hope you each get every ounce of energy are willing to be here LTUE would cease to exist. I out that you can. I hope that by the end of this year’s would like to particularly express my gratitude to the symposium you find yourself ready to take on anything. -

THE GETAWAY GIRL: a NOVEL and CRITICAL INTRODUCTION By

THE GETAWAY GIRL: A NOVEL AND CRITICAL INTRODUCTION By EMILY CHRISTINE HOFFMAN Bachelor of Arts in English University of Kansas Lawrence, Kansas 1999 Master of Arts in English University of Kansas Lawrence, Kansas 2002 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2009 THE GETAWAY GIRL: A NOVEL AND CRITICAL INTRODUCTION Dissertation Approved: Jon Billman Dissertation Adviser Elizabeth Grubgeld Merrall Price Lesley Rimmel Ed Walkiewicz A. Gordon Emslie Dean of the Graduate College ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my appreciation to several people for their support, friendship, guidance, and instruction while I have been working toward my PhD. From the English department faculty, I would like to thank Dr. Robert Mayer, whose “Theories of the Novel” seminar has proven instrumental to both the development of The Getaway Girl and the accompanying critical introduction. Dr. Elizabeth Grubgeld wisely recommended I include Elizabeth Bowen’s The House in Paris as part of my modernism reading list. Without my knowledge of that novel, I am not sure how I would have approached The Getaway Girl’s major structural revisions. I have also appreciated the efforts of Dr. William Decker and Dr. Merrall Price, both of whom, in their role as Graduate Program Director, have generously acted as my advocate on multiple occasions. In addition, I appreciate Jon Billman’s willingness to take the daunting role of adviser for an out-of-state student he had never met. Thank you to all the members of my committee—Prof. -

Exploring Kodiak Alutiiq Literature Through Core Values

LIITUKUT SUGPIAT’STUN (WE ARE LEARNING HOW TO BE REAL PEOPLE): EXPLORING KODIAK ALUTIIQ LITERATURE THROUGH CORE VALUES A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the University of Alaska Fairbanks in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Alisha Susana Drabek, BA., M.F.A. Fairbanks, Alaska December 2012 UMI Number: 3537832 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3537832 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 LIITUKUT SUGPIAT’ STUN (WE ARE LEARNING HOW TO BE REAL PEOPLE): EXPLORING KODIAK ALUTIIQ LITERATURE THROUGH CORE VALUES By Alisha Susana Drabek Abstract The decline of Kodiak Alutiiq oral tradition practices and limited awareness or understanding of archived stories has kept them from being integrated into school curriculum. This study catalogs an anthology of archived Alutiiq literature documented since 1804, and provides an historical and values-based analysis of Alutiiq literature, focused on the educational significance of stories as tools for individual and community wellbeing. The study offers an exploration of values, worldview and knowledge embedded in Alutiiq stories. -

German Fairy-Tale Figures in American Pop Culture

CRAVING SUPERNATURAL CREATURES Series in Fairy- Tale Studies General Editor Donald Haase, Wayne State University Advisory Editors Cristina Bacchilega, University of Hawai‘i, Mānoa Stephen Benson, University of East Anglia Nancy L. Canepa, Dartmouth College Anne E. Duggan, Wayne State University Pauline Greenhill, University of Winnipeg Christine A. Jones, University of Utah Janet Langlois, Wayne State University Ulrich Marzolph, University of Göttingen Carolina Fernández Rodríguez, University of Oviedo Maria Tatar, Harvard University Jack Zipes, University of Minnesota A complete listing of the books in this series can be found online at wsupress.wayne.edu CRAVING SUPERNATURAL CREATURES German Fairy- Tale Figures in American Pop Culture CLAUDIA SCHWABE Wayne State University Press Detroit © 2019 by Wayne State University Press, Detroit, Michigan 48201. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without formal permission. Manufactured in the United States of America. ISBN 978- 0- 8143- 4196- 4 (paperback) ISBN 978- 0- 8143- 4601- 3 (hardcover) ISBN 978- 0- 8143- 4197- 1 (e- book) Library of Congress Control Number: 2018966275 Published with the assistance of a fund established by Thelma Gray James of Wayne State University for the publication of folklore and English studies. Wayne State University Press Leonard N. Simons Building 4809 Woodward Avenue Detroit, Michigan 48201-1309 Visit us online at wsupress .wayne .edu Dedicated to my parents, Dr. Roman and Cornelia Schwabe s CONTENTS Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 s 1. Reimagining Uncanny Fairy- Tale s Creatures: Automatons, Golems, and Doppelgangers 13 2. Evil Queens and Witches: Mischievous Villains or Misunderstood Victims? 87 3. Taming the Monstrous Other: Representations of the Rehabilitated Big Bad Beast in American Media 155 4. -

Souvenir Book Is Copyright ©2011 by Arisia, Inc., a Non-Profit, Tax-Exempt, 501(C)(3) Corporation

Arisia 2011 Jan 14-17, 2011 Westin Waterfront Hotel, Boston, MA 2 Arisia 2011 Arisia 2011 Westin Waterfront Hotel Boston, Massachusetts “Mad Science” Writer Guest of Honor Kelley Armstrong Artist Guest of Honor Josh Simpson Webcomic Guest of Honor Shaenon Garrity Fan Guest of Honor René Walling Special Guest Seanan McGuire Content From the Convention Chair .......................................4 From the Corporate President ...................................5 Arisia 2011 Committee ..............................................6 Arisia Code of Conduct .............................................8 Arisia from A to Z ....................................................10 The Carl Brandon Awards .......................................14 Arisia Abbreviated History ......................................16 Writer Guest of Honor Kelley Armstrong ...............20 Checkmate, a short story by Kelley Armstrong ...........21 Fan Guest of Honor René Walling ..........................24 Special Guest Seanan McGuire ...............................25 Webcomic Guest of Honor Shaenon Garrity ..........26 Artist Guest of Honor Josh Simpson .......................30 Arisia 2011 Participants ...........................................34 The Arisia 2011 Souvenir Book is copyright ©2011 by Arisia, Inc., a non-profit, tax-exempt, 501(c)(3) corporation. Arisia is a service mark of Arisia, Inc. All bylined articles are copyright ©2011 by their authors. Checkmate is copyright Kelley Armstrong and used by permission of the author. Images, including sketches by Seanan Garrity and photographs, are supplied and used by permission of their creators. Colophon: This publication was typeset with Baskerville, Berthold Akzidenz Grotesk and Mason. January 14-17 3 Welcome to Arisia! While we are devouring a novel, engrossed in a possibility and hard work. The weekend never piece of art, or enveloped by various works of fails to surprise and delight, every year, as we media, we believe in the truth that the creator grow and change in the community. -

David Blamires Telling Tales the Impact of Germany on English Children’S Books 1780-1918 to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

David Blamires Telling Tales The Impact of Germany on English Children’s Books 1780-1918 To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/23 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. TELLING TALES David Blamires (University of Manchester) is the author of around 100 arti- cles on a variety of German and English topics and of publications includ- ing Characterization and Individuality in Wolfram’s ‘Parzival’; David Jones: Art- ist and Writer; Herzog Ernst and the Otherworld Journey: a Comparative Study; Happily Ever After: Fairytale Books through the Ages; Margaret Pilkington 1891- 1974; Fortunatus in His Many English Guises; Robin Hood: a Hero for all Times and The Books of Jonah. He also guest-edited a special number of the Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester on Children’s Literature. [Christoph von Schmid], The Basket of Flowers; or, Piety and Truth Triumphant (London, [1868]). David Blamires Telling Tales The Impact of Germany on English Children’s Books 1780-1918 Cambridge 2009 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com @ 2009 David Blamires Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. This license allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author attribution is clearly stated. -

Reworkings in the Textual History of Gulliver's Travels: a Translational

Reworkings in the textual history of Gulliver’s Travels: a translational approach Alice Colombo The thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Portsmouth August 2013 ii ABSTRACT On 28 October 1726 Gulliver’s Travels debuted on the literary scene as a political and philosophical satire meant to provoke and entertain an audience of relatively educated and wealthy British readers. Since then, Swift’s work has gradually evolved, assuming multiple forms and meanings while becoming accessible and attractive to an increasingly broad readership in and outside Britain. My study emphasises that reworkings, including re-editions, translations, abridgments, adaptations and illustrations, have played a primary role in this process. Its principal aim is to investigate how reworkings contributed to the popularity of Gulliver’s Travels by examining the dynamics and the stages through which they transformed its text and its original significance. Central to my research is the assumption that this transformation is largely the result of shifts of a translational nature and that, therefore, the analysis of reworkings and the understanding of their role can greatly benefit from the models of translation description devised in Descriptive Translation Studies. The reading of reworkings as entailing processes of translation shows how derivative creations operate collaboratively to ensure literary works’ continuous visibility and actively shape the literary polysystem. The study opens with an exploration of existing approaches to reworkings followed by an examination of the characteristics which exposed Gulliver’s Travels to continuous rethinking and reworking. Emphasis is put on how the work’s satirical significance gave rise to a complex early textual problem for which Gulliver’s Travels can be said to have debuted on the literary scene as a derivative production in the first place. -

Television Academy

Television Academy 2014 Primetime Emmy Awards Ballot Outstanding Sound Mixing For A Comedy Or Drama Series (One Hour) For a single episode of a comedy or drama series. Emmy(s) to a maximum of four mixers. Production and post-production mixers are all eligible. NOTE: VOTE FOR NO MORE THAN FIVE achievements in this category that you have seen and feel are worthy of nomination. (More than five votes in this category will void all votes in this category.) 001 Banshee Bullets And Tears March 14, 2014 Lucas and Carrie reflect on their Capital Diamond heist 15 years ago as they gear up to battle Rabbit. After his army is decimated in a blazing gunfight, Rabbit’s end comes quietly and by his own hand. Rebecca kills Alex Longshadow while Emmett and his wife are murdered by Neo-Nazis. 002 Bates Motel Shadow Of A Doubt March 10, 2014 Norma tries to distract Norman from his obsession with Miss Watson by auditioning for a play. A new player in town has Dylan and Remo on edge. 003 Being Mary Jane Storm Advisory January 7, 2014 Andre comes face to face with David at Mary Jane's house in an encounter that leaves Mary Jane convinced both men are none the wiser. 004 Black Sails V. February 22, 2014 Flint and the Walrus crew play a deadly chess match on the open sea. Richard forces Eleanor’s hand. Rackham makes a career change. Bonny confesses to Max. 005 The Blacklist The Palovich Brothers April 21, 2014 The Pavlovich Brothers specialize in abductions of high value targets and according to Red they are planning their next hit. -

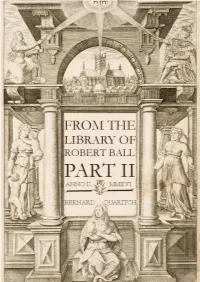

The Library of Robert Ball: Part Ii

BERNARD QUARITCH LTD. 40 SOUTH AUDLEY ST, LONDON W1K 2PR Tel: +44 (0)20-7297 4888 Fax: +44 (0)20-7297 4866 e-mail: [email protected] web site: www.quaritch.com Bankers: Barclays Bank plc, 50 Pall Mall, P.O. Box 15162, London SW1A 1QB Sort code: 20-65-82 Swift code: BARCGB22 Sterling account: IBAN: GB98 BARC 206582 10511722 Euro account: IBAN: GB30 BARC 206582 45447011 U.S. Dollar account: IBAN: GB46 BARC 206582 63992444 VAT number: GB 840 1358 54 MasterCard, Visa, and American Express accepted Recent Catalogues: 1433 English Books and Manuscripts 1432 Continental Books 1431 Travel & Exploration, Natural History Recent Lists: 2016/1 Human Sciences 2015/9 Early Drama 2015/8 Flora and Fauna 2015/7 Classics 2015/6 Design and Interiors 2015/5 Library of Robert Ball, Part I List 2016/2 Cover image from item 57. © Bernard Quaritch 2016 FROM THE LIBRARY OF ROBERT BALL: PART II English Literature 1500-1900, an American Journalist’s Collection Collecting rare books is a selfish pastime. It is about possession, about ownership. After all, the texts are universally available. Even the books themselves are often accessible in public libraries. But that is not the same as having them in one’s own bookcase. I have been an active collector for most of a long life. Now, in my 90th year, I have decided it is time to pass my pleasure on to others. Robert Ball 1) AUBREY, John. Miscellanies, viz. I. Day-Fatality. II. Local-Fatality. III. Ostenta. IV. Omens. V. Dreams. VI. Apparitions. VII. Voices.