German Fairy-Tale Figures in American Pop Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPA : Redesigning Animation

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. UPA : redesigning animation Bottini, Cinzia 2016 Bottini, C. (2016). UPA : redesigning animation. Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/69065 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/69065 Downloaded on 05 Oct 2021 20:18:45 SGT UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI SCHOOL OF ART, DESIGN AND MEDIA 2016 UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI School of Art, Design and Media A thesis submitted to the Nanyang Technological University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.” Paul Klee, “Creative Credo” Acknowledgments When I started my doctoral studies, I could never have imagined what a formative learning experience it would be, both professionally and personally. I owe many people a debt of gratitude for all their help throughout this long journey. I deeply thank my supervisor, Professor Heitor Capuzzo; my cosupervisor, Giannalberto Bendazzi; and Professor Vibeke Sorensen, chair of the School of Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore for showing sincere compassion and offering unwavering moral support during a personally difficult stage of this Ph.D. I am also grateful for all their suggestions, critiques and observations that guided me in this research project, as well as their dedication and patience. My gratitude goes to Tee Bosustow, who graciously -

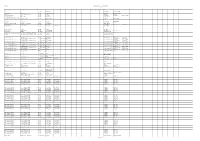

(TMIIIP) Paid Projects Through August 31, 2020 Report Created 9/29/2020

Texas Moving Image Industry Incentive Program (TMIIIP) Paid Projects through August 31, 2020 Report Created 9/29/2020 Company Project Classification Grant Amount In-State Spending Date Paid Texas Jobs Electronic Arts Inc. SWTOR 24 Video Game $ 212,241.78 $ 2,122,417.76 8/19/2020 26 Tasmanian Devil LLC Tasmanian Devil Feature Film $ 19,507.74 $ 260,103.23 8/18/2020 61 Tool of North America LLC Dick's Sporting Goods - DecembeCommercial $ 25,660.00 $ 342,133.35 8/11/2020 53 Powerhouse Animation Studios, In Seis Manos (S01) Television $ 155,480.72 $ 1,554,807.21 8/10/2020 45 FlipNMove Productions Inc. Texas Flip N Move Season 7 Reality Television $ 603,570.00 $ 4,828,560.00 8/6/2020 519 FlipNMove Productions Inc. Texas Flip N Move Season 8 (13 E Reality Television $ 305,447.00 $ 2,443,576.00 8/6/2020 293 Nametag Films Dallas County Community CollegeCommercial $ 14,800.28 $ 296,005.60 8/4/2020 92 The Lost Husband, LLC The Lost Husband Feature Film $ 252,067.71 $ 2,016,541.67 8/3/2020 325 Armature Studio LLC Scramble Video Game $ 33,603.20 $ 672,063.91 8/3/2020 19 Daisy Cutter, LLC Hobby Lobby Christmas 2019 Commercial $ 10,229.82 $ 136,397.63 7/31/2020 31 TVM Productions, Inc. Queen Of The South - Season 2 Television $ 4,059,348.19 $ 18,041,547.51 5/1/2020 1353 Boss Fight Entertainment, Inc Zombie Boss Video Game $ 268,650.81 $ 2,149,206.51 4/30/2020 17 FlipNMove Productions Inc. -

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

An Analysis of Violence and Conflict in Indigenous- Canadian Government Relations, and Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Lund University Publications - Student Papers Lund University – Graduate School SIMV07 Master’s of Science in Global Studies Term: Spring 2015 Department of Political Science Supervisor: Erik Ringmar La plus ça change, la plus ça reste la même An analysis of violence and conflict in Indigenous- Canadian government relations, and missing and murdered Indigenous women Shane Isler “La plus ça change, la plus ça reste la même” - An epigram by the author Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr, which translates as “The more it changes, the more it remains the same.” Shane Isler Master’s of Science in Global Studies Lund University Abstract The aim of this thesis is to investigate the Canadian government’s stance on addressing the issue of missing and murdered Indigenous women, and to perform an analysis of ongoing violence and asymmetric conflict in Indigenous- Government of Canada relations. The Canadian government’s approach in regards to holding a national inquiry into the issue of missing and murdered Indigenous women in Canada was placed into the broader context of Indigenous peoples in Canada in order to understand the logic behind the government’s refusal and response. This was done by performing a deductive thematic analysis on gathered discourse and developed context, drawing the applied themes from the forms of violence outlined in Galtung’s violence triangle. As the results of the analysis indicated the clear presence of violence, both in the situation of missing and murdered Indigenous women as well as the broader context of relations, Galtung’s conflict triangle was employed to understand the significance of this violence. -

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary Ingo Gildenhard https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Ingo Gildenhard The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the author(s), but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work. Attribution should include the following information: Ingo Gildenhard, Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119. Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018. https://doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0156 Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/845#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www. -

DACIN SARA Repartitie Aferenta Trimestrului III 2019 Straini TITLU

DACIN SARA Repartitie aferenta trimestrului III 2019 Straini TITLU TITLU ORIGINAL AN TARA R1 R2 R3 R4 R5 R6 R7 R8 R9 R10 R11 S1 S2 S3 S4 S5 S6 S7 S8 S9 S10 S11 S12 S13 S14 S15 Greg Pruss - Gregory 13 13 2010 US Gela Babluani Gela Babluani Pruss 1000 post Terra After Earth 2013 US M. Night Shyamalan Gary Whitta M. Night Shyamalan 30 de nopti 30 Days of Night: Dark Days 2010 US Ben Ketai Ben Ketai Steve Niles 300-Eroii de la Termopile 300 2006 US Zack Snyder Kurt Johnstad Zack Snyder Michael B. Gordon 6 moduri de a muri 6 Ways to Die 2015 US Nadeem Soumah Nadeem Soumah 7 prichindei cuceresc Broadway-ul / Sapte The Seven Little Foys 1955 US Melville Shavelson Jack Rose Melville Shavelson prichindei cuceresc Broadway-ul A 25-a ora 25th Hour 2002 US Spike Lee David Benioff Elaine Goldsmith- A doua sansa Second Act 2018 US Peter Segal Justin Zackham Thomas A fost o data in Mexic-Desperado 2 Once Upon a Time in Mexico 2003 US Robert Rodriguez Robert Rodriguez A fost odata Curly Once Upon a Time 1944 US Alexander Hall Lewis Meltzer Oscar Saul Irving Fineman A naibii dragoste Crazy, Stupid, Love. 2011 US Glenn Ficarra John Requa Dan Fogelman Abandon - Puzzle psihologic Abandon 2002 US Stephen Gaghan Stephen Gaghan Acasa la coana mare 2 Big Momma's House 2 2006 US John Whitesell Don Rhymer Actiune de recuperare Extraction 2013 US Tony Giglio Tony Giglio Acum sunt 13 Ocean's Thirteen 2007 US Steven Soderbergh Brian Koppelman David Levien Acvila Legiunii a IX-a The Eagle 2011 GB/US Kevin Macdonald Jeremy Brock - ALCS Les aventures extraordinaires d'Adele Blanc- Adele Blanc Sec - Aventurile extraordinare Luc Besson - Sec - The Extraordinary Adventures of Adele 2010 FR/US Luc Besson - SACD/ALCS ale Adelei SACD/ALCS Blanc - Sec Adevarul despre criza Inside Job 2010 US Charles Ferguson Charles Ferguson Chad Beck Adam Bolt Adevarul gol-golut The Ugly Truth 2009 US Robert Luketic Karen McCullah Kirsten Smith Nicole Eastman Lebt wohl, Genossen - Kollaps (1990-1991) - CZ/DE/FR/HU Andrei Nekrasov - Gyoergy Dalos - VG. -

Gender and Fairy Tales

Issue 2013 44 Gender and Fairy Tales Edited by Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier ISSN 1613-1878 About Editor Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier Gender forum is an online, peer reviewed academic University of Cologne journal dedicated to the discussion of gender issues. As English Department an electronic journal, gender forum offers a free-of- Albertus-Magnus-Platz charge platform for the discussion of gender-related D-50923 Köln/Cologne topics in the fields of literary and cultural production, Germany media and the arts as well as politics, the natural sciences, medicine, the law, religion and philosophy. Tel +49-(0)221-470 2284 Inaugurated by Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier in 2002, the Fax +49-(0)221-470 6725 quarterly issues of the journal have focused on a email: [email protected] multitude of questions from different theoretical perspectives of feminist criticism, queer theory, and masculinity studies. gender forum also includes reviews Editorial Office and occasionally interviews, fictional pieces and poetry Laura-Marie Schnitzler, MA with a gender studies angle. Sarah Youssef, MA Christian Zeitz (General Assistant, Reviews) Opinions expressed in articles published in gender forum are those of individual authors and not necessarily Tel.: +49-(0)221-470 3030/3035 endorsed by the editors of gender forum. email: [email protected] Submissions Editorial Board Target articles should conform to current MLA Style (8th Prof. Dr. Mita Banerjee, edition) and should be between 5,000 and 8,000 words in Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (Germany) length. Please make sure to number your paragraphs Prof. Dr. Nilufer E. Bharucha, and include a bio-blurb and an abstract of roughly 300 University of Mumbai (India) words. -

Hunt on for Bomber Set for Sunday Liquor County Commissioners to Accept Input on Idea Requested by Restaurants

1A WEDNESDAY, APRIL 17, 2013 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | 75¢ Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM Pat Summerall dies at 82 Summerall, famous for his deep, reso- tennis. He taught middle See related story, page 6A Area residents recall nant voice, called 16 Super Bowls as the school English, and always famed broadcaster who play-by-play announcer. He spent more remembered where he Summerall jumped out of the boat and than 40 years as the voice of the National came from, according to hightailed it to his truck -- wanting to leave was born and raised here. Football League. friends and family. the boat behind because the gnats were so By DEREK GILLIAM But before he was a nationally known One time, after a night bad, Kennon said. [email protected] broadcaster, Summerall was born and when the gnats were like “I told him to back the trailer up, and raised here in Lake City. Summerall a buzzing cloud at the that if he wanted to give the boat away, I Lake City’s own Pat Summerall passed He loved to fish on the Suwannee River, river, Summerall had had would take it,” he said. away Tuesday of heart failure. He was 82 but hated the sand gnats. He was all- enough, Summerall’s first cousin Mike years old. conference in football, basketball and Kennon said. SUMMERALL continued on 3A Hearing Hunt on for bomber set for Sunday liquor County commissioners to accept input on idea requested by restaurants. By DEREK GILLIAM [email protected] Sunday sales of liquor could soon be a reality in Columbia County as the coun- ty commission will hold a public hearing on the issue at Thursday’s meeting. -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

Mais Où Sont Les Blanche Neige D'antan? Étude Culturelle D'un Conte

Mais où sont les Blanche Neige d’antan ? Étude culturelle d’un conte socialisé Christian Chelebourg To cite this version: Christian Chelebourg. Mais où sont les Blanche Neige d’antan ? Étude culturelle d’un conte socialisé. Cahiers Robinson, Centre de recherches littéraires Imaginaire et didactique (Arras), 2015, Civiliser la jeunesse (Colloque de Cerisy), pp.83-100. hal-02168777 HAL Id: hal-02168777 https://hal.univ-lorraine.fr/hal-02168777 Submitted on 29 Jun 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Référence bibliographique de l’article : Christian Chelebourg, « Mais où sont les Blanche- Neige d’antan ? Étude culturelle d’un conte socialisé », Les Cahiers Robinson, n° 38, octobre 2015, « Civiliser la jeunesse (colloque de Cerisy) », pp. 83-100. Mais où sont les Blanche-Neige d’antan ? Étude culturelle d’un conte socialisé Christian CHELEBOURG De tous les préjugés sur la littérature et les fictions de jeunesse, la configuration des mœurs est sans doute le mieux partagé. Pour l’opinion publique, on devient ce qu’on a lu, ce qu’on a regardé, à l’âge tendre. D’où les cris d’orfraie des censeurs de tout poil sur « ce qu’on met entre les mains de nos enfants ». -

Cultural Analysis an Interdisciplinary Forum on Folklore and Popular Culture

CULTURAL ANALYSIS AN INTERDISCIPLINARY FORUM ON FOLKLORE AND POPULAR CULTURE Vol. 17.2 Cover image: Gesar statue and performance in Yushu, 2014. Photo by Timothy Thurston CULTURAL ANALYSIS AN INTERDISCIPLINARY FORUM ON FOLKLORE AND POPULAR CULTURE Vol. 17.2 © 2020 by The University of California Editorial Board Pertti J. Anttonen, University of Eastern Finland, Finland Hande Birkalan, Yeditepe University, Istanbul, Turkey Charles Briggs, University of California, Berkeley, U.S.A. Anthony Bak Buccitelli, Pennsylvania State University, Harrisburg, U.S.A. Oscar Chamosa, University of Georgia, U.S.A. Chao Gejin, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, China Valdimar Tr. Hafstein, University of Iceland, Reykjavik Jawaharlal Handoo, Central Institute of Indian Languages, India Galit Hasan-Rokem, The Hebrew University, Jerusalem James R. Lewis, University of Tromsø, Norway Fabio Mugnaini, University of Siena, Italy Sadhana Naithani, Jawaharlal Nehru University, India Peter Shand, University of Auckland, New Zealand Francisco Vaz da Silva, University of Lisbon, Portugal Maiken Umbach, University of Nottingham, England Ülo Valk, University of Tartu, Estonia Fionnuala Carson Williams, Northern Ireland Environment Agency Ulrika Wolf-Knuts, Åbo Academy, Finland Editorial Collective Senior Editors: Sophie Elpers, Karen Miller Associate Editors: Andrea Glass, Robert Guyker, Jr., Semontee Mitra Review Editor: Spencer Green Copy Editors: Megan Barnes, Jean Bascom, Nate Davis, Riley Griffith, Cory Hutcheson, Alice Markham-Cantor, Anna O’Brien, Joy Tang, Natalie Tsang Website Manager: Kiesha Oliver Table of Contents Timothy Thurston Assessing the Sustainability of the Gesar Epic in Northwest China, Thoughts from Yul shul (Yushu) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture.........................................1 Response: Marc Jacobs Aleksandra Gruszczyk The Punisher: A Cultural Image of the ‘Moral Wound’.....................................................24 Response: Daniel Peretti Book Reviews Brant W. -

Catching Fire. the Impressive Lineup Is Joined by the Hunger Games

Cast: Jennifer Lawrence, Josh Hutcherson, Liam Hemsworth, Woody Harrelson, Elizabeth Banks, Julianne Moore, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Jeffrey Wright, Willow Shields, Sam Claflin, Jena Malone, Natalie Dormer, with Stanley Tucci, and Donald Sutherland Directed by: Francis Lawrence Screenplay by: Peter Craig and Danny Strong Based upon: The novel “Mockingjay” by Suzanne Collins Produced by: Nina Jacobson, Jon Kilik SYNOPSIS The blockbuster Hunger Games franchise has taken audiences by storm around the world, grossing more than $2.2 billion at the global box office. The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 2 now brings the franchise to its powerful final chapter in which Katniss Everdeen [Jennifer Lawrence] realizes the stakes are no longer just for survival – they are for the future. With the nation of Panem in a full scale war, Katniss confronts President Snow [Donald Sutherland] in the final showdown. Teamed with a group of her closest friends – including Gale [Liam Hemsworth], Finnick [Sam Claflin] and Peeta [Josh Hutcherson] – Katniss goes off on a mission with the unit from District 13 as they risk their lives to liberate the citizens of Panem, and stage an assassination attempt on President Snow who has become increasingly obsessed with destroying her. The mortal traps, enemies, and moral choices that await Katniss will challenge her more than any arena she faced in The Hunger Games. The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 2 is directed by Francis Lawrence from a screenplay by Peter Craig and Danny Strong and features an acclaimed cast including Academy Award®-winner Jennifer Lawrence, Josh Hutcherson, Liam Hemsworth, Woody Harrelson, Elizabeth Banks, Academy Award®-winner Philip Seymour Hoffman, Jeffrey Wright, Willow Shields, Sam Claflin, Jena Malone with Stanley Tucci and Donald Sutherland reprising their original roles from The Hunger Games and The Hunger Games: Catching Fire.