Cultural Analysis an Interdisciplinary Forum on Folklore and Popular Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic

Please do not remove this page Giving Evil a Name: Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic Croft, Janet Brennan https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643454990004646?l#13643522530004646 Croft, J. B. (2015). Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic. Slayage: The Journal of the Joss Whedon Studies Association, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.7282/T3FF3V1J This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/10/02 09:39:58 -0400 Janet Brennan Croft1 Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic “It’s about power. Who’s got it. Who knows how to use it.” (“Lessons” 7.1) “I would suggest, then, that the monsters are not an inexplicable blunder of taste; they are essential, fundamentally allied to the underlying ideas of the poem …” (J.R.R. Tolkien, “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics”) Introduction: Names and Blood in the Buffyverse [1] In Joss Whedon’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003) and Angel (1999- 2004), words are not something to be taken lightly. A word read out of place can set a book on fire (“Superstar” 4.17) or send a person to a hell dimension (“Belonging” A2.19); a poorly performed spell can turn mortal enemies into soppy lovebirds (“Something Blue” 4.9); a word in a prophecy might mean “to live” or “to die” or both (“To Shanshu in L.A.” A1.22). -

Mais Où Sont Les Blanche Neige D'antan? Étude Culturelle D'un Conte

Mais où sont les Blanche Neige d’antan ? Étude culturelle d’un conte socialisé Christian Chelebourg To cite this version: Christian Chelebourg. Mais où sont les Blanche Neige d’antan ? Étude culturelle d’un conte socialisé. Cahiers Robinson, Centre de recherches littéraires Imaginaire et didactique (Arras), 2015, Civiliser la jeunesse (Colloque de Cerisy), pp.83-100. hal-02168777 HAL Id: hal-02168777 https://hal.univ-lorraine.fr/hal-02168777 Submitted on 29 Jun 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Référence bibliographique de l’article : Christian Chelebourg, « Mais où sont les Blanche- Neige d’antan ? Étude culturelle d’un conte socialisé », Les Cahiers Robinson, n° 38, octobre 2015, « Civiliser la jeunesse (colloque de Cerisy) », pp. 83-100. Mais où sont les Blanche-Neige d’antan ? Étude culturelle d’un conte socialisé Christian CHELEBOURG De tous les préjugés sur la littérature et les fictions de jeunesse, la configuration des mœurs est sans doute le mieux partagé. Pour l’opinion publique, on devient ce qu’on a lu, ce qu’on a regardé, à l’âge tendre. D’où les cris d’orfraie des censeurs de tout poil sur « ce qu’on met entre les mains de nos enfants ». -

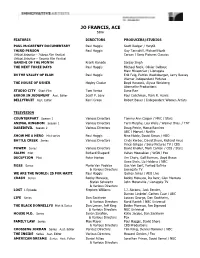

JO FRANCIS, ACE Editor

JO FRANCIS, ACE Editor FEATURES DIRECTORS PRODUCERS/STUDIOS PAUL McCARTNEY DOCUMENTARY Paul Haggis Scott Rodger / Hwy61 THIRD PERSON Paul Haggis Guy Tannahill, Michael Nozik Official Selection - Tribeca Film Festival Corsan / Sony Pictures Classics Official Selection – Toronto Film Festival GANDHI OF THE MONTH Kranti Kanade Sanjay Singh THE NEXT THREE DAYS Paul Haggis Michael Nozik, Olivier Delbosc Marc Missonnier / Lionsgate IN THE VALLEY OF ELAH Paul Haggis Erik Feig, Patrick Wachsberger, Larry Becsey Warner Independent Pictures THE HOUSE OF USHER Hayley Cloake Boyd Hancock, Alyssa Weisberg Abernathy Productions STUDIO CITY Short Film Tom Verica Dana Rae ERROR IN JUDGMENT Asst. Editor Scott P. Levy Paul Colichman, Mark R. Harris BELLYFRUIT Asst. Editor Kerri Green Robert Bauer / Independent Women Artists TELEVISION COUNTERPART Season 1 Various Directors Tammy Ann Casper / MRC / Starz ANIMAL KINGDOM Season 1 Various Directors Terri Murphy, Lou Wells / Warner Bros. / TNT DAREDEVIL Season 2 Various Directors Doug Petrie, Marco Ramirez ABC / Marvel / Netflix SHOW ME A HERO Mini-series Paul Haggis Nina Noble, David Simon / HBO BATTLE CREEK Series Various Directors Cindy Kerber, David Shore, Richard Heus Vince Gilligan / Sony Pictures TV / CBS POWER Series Various Directors David Knoller, Mark Canton / CBS / Starz SALEM Pilot Richard Shepard Vahan Moosekian / WGN / Fox DECEPTION Pilot Peter Horton Jim Chory, Gail Berman, Lloyd Braun Gene Stein, Liz Heldens / NBC BOSS Series Mario Van Peebles Gus Van Sant, Farhad Safinia & Various Directors Lionsgate TV WE ARE THE WORLD: 25 FOR HAITI Paul Haggis Quincy Jones / AEG Live CRASH Series Bobby Moresco, Bobby Moresco, Ira Behr, Glen Mazzara Stefan Schwartz John Moranville / Lionsgate TV & Various Directors LOST 1 Episode Stephen Williams J.J. -

Two Family Members Die in I-80 Rollover

FRONT PAGE A1 www.tooeletranscript.com TUESDAY TOOELE RANSCRIPT Two local players T compete against each other at college level See A9 BULLETIN October 2, 2007 SERVING TOOELE COUNTY SINCE 1894 VOL. 114 NO. 38 50¢ Two family members die in I-80 rollover by Suzanne Ashe injured in the wreck. He was victims to the hospital. STAFF WRITER one of seven people who were Jose Magdeleno, 9, Yadira thrown from the vehicle when it Miranda, 5, and Amie Cano, Two members of the same rolled several times. 5, were all flown to Primary family died as a result of a The car was speeding when it Children’s Hospital. crash near Delle on I-80 Sunday drifted to the left before Cano- Gutierrez said the family may night. Magdeleno overcorrected to the have been coming back from According to Utah Highway right and the car went off the Wendover. Patrol Trooper Sgt. Robert road, Gutierrez said. All eastbound lanes were Gutierrez, the single-vehicle Cano-Magdeleno’s wife, closed for about an hour after rollover occurred at 7:20 p.m. Roxanna Guatalupe Miranda, the accident, and lane No. 2 was near mile post 69. 22, and the driver’s daugh- closed for about three hours. Gutierrez said alcohol was ter Emily Cano, 10 were killed. Gutierrez said no one in the a factor, and open containers Dalila Marisol Cano, 39, is in two-door 1988 Ford Escort was were found at the scene. critical condition. wearing a seat belt. Photo courtesy of Utah Highway Patrol The driver, Jose J. -

DVD List As of 2/9/2013 2 Days in Paris 3 Idiots 4 Film Favorites(Secret

A LIST OF THE NEWEST DVDS IS LOCATED ON THE WALL NEXT TO THE DVD SHELVES DVD list as of 2/9/2013 2 Days in Paris 3 Idiots 4 Film Favorites(Secret Garden, The Witches, The Neverending Story, 5 Children & It) 5 Days of War 5th Quarter, The $5 A Day 8 Mile 9 10 Minute Solution-Quick Tummy Toners 10 Minute Solution-Dance off Fat Fast 10 Minute Solution-Hot Body Boot Camp 12 Men of Christmas 12 Rounds 13 Ghosts 15 Minutes 16 Blocks 17 Again 21 21 Jumpstreet (2012) 24-Season One 25 th Anniversary Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Concerts 28 Weeks Later 30 Day Shred 30 Minutes or Less 30 Years of National Geographic Specials 40-Year-Old-Virgin, The 50/50 50 First Dates 65 Energy Blasts 13 going on 30 27 Dresses 88 Minutes 102 Minutes That Changed America 127 Hours 300 3:10 to Yuma 500 Days of Summer 9/11 Commission Report 1408 2008 Beijing Opening Ceremony 2012 2016 Obama’s America A-Team, The ABCs- Little Steps Abandoned Abandoned, The Abduction About A Boy Accepted Accidental Husband, the Across the Universe Act of Will Adaptation Adjustment Bureau, The Adventures of Sharkboy & Lavagirl in 3-D Adventures of Teddy Ruxpin-Vol 1 Adventures of TinTin, The Adventureland Aeonflux After.Life Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-The Murder of Roger Ackroyd Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Sad Cypress Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-The Hollow Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Five Little Pigs Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Lord Edgeware Dies Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Evil Under the Sun Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Murder in Mespotamia Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Death on the Nile Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Taken at -

German Fairy-Tale Figures in American Pop Culture

CRAVING SUPERNATURAL CREATURES Series in Fairy- Tale Studies General Editor Donald Haase, Wayne State University Advisory Editors Cristina Bacchilega, University of Hawai‘i, Mānoa Stephen Benson, University of East Anglia Nancy L. Canepa, Dartmouth College Anne E. Duggan, Wayne State University Pauline Greenhill, University of Winnipeg Christine A. Jones, University of Utah Janet Langlois, Wayne State University Ulrich Marzolph, University of Göttingen Carolina Fernández Rodríguez, University of Oviedo Maria Tatar, Harvard University Jack Zipes, University of Minnesota A complete listing of the books in this series can be found online at wsupress.wayne.edu CRAVING SUPERNATURAL CREATURES German Fairy- Tale Figures in American Pop Culture CLAUDIA SCHWABE Wayne State University Press Detroit © 2019 by Wayne State University Press, Detroit, Michigan 48201. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without formal permission. Manufactured in the United States of America. ISBN 978- 0- 8143- 4196- 4 (paperback) ISBN 978- 0- 8143- 4601- 3 (hardcover) ISBN 978- 0- 8143- 4197- 1 (e- book) Library of Congress Control Number: 2018966275 Published with the assistance of a fund established by Thelma Gray James of Wayne State University for the publication of folklore and English studies. Wayne State University Press Leonard N. Simons Building 4809 Woodward Avenue Detroit, Michigan 48201-1309 Visit us online at wsupress .wayne .edu Dedicated to my parents, Dr. Roman and Cornelia Schwabe s CONTENTS Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 s 1. Reimagining Uncanny Fairy- Tale s Creatures: Automatons, Golems, and Doppelgangers 13 2. Evil Queens and Witches: Mischievous Villains or Misunderstood Victims? 87 3. Taming the Monstrous Other: Representations of the Rehabilitated Big Bad Beast in American Media 155 4. -

JAN JERICHO PRODUCTION DESIGNER Janjericho.Com

JAN JERICHO PRODUCTION DESIGNER JanJericho.com TELEVISION CITY ON A HILL Showtime Prod: Ben Affleck, Kevin Bacon, Matt Damon Dir: Various (Season 2) (Production Designer) THE MARVELOUS MRS. MAISEL Amazon Prod: Dan Palladino, Dhana Gilbert Dir: Amy Sherman-Palladino (Season 2) (Art Director) ODD MOM OUT Jax Media/Bravo Prod: Lara Spotts, Ken Druckerman Dir: Various (Season 3) (Art Director) MASTER OF NONE Universal TV/Netflix Prod: Aziz Ansari, Alan Yang, Michael Schur Dir: Various (Season 2) (Art Director) CRASHING HBO Prod: Pete Holmes, Judd Apatow Dir: Various (Seasons 1 & 2) (Art Director) Igor Srubshchik TIME AFTER TIME Warner Bros. TV/ABC Prod: Kevin Williamson, Michael Stricks Dir: Marcos Siega (Pilot) (Art Director) DAREDEVIL Marvel/Netflix Prod: Doug Petrie, Marco Ramirez Dir: Various (Season 2) (Art Director) Michael Stricks FEATURES AND SO IT GOES (Art Director) ASIG LLC Prod: Mark Damon, Alan Greisman Dir: Rob Reiner PICCO Walker und Worm Film Prod: Tobias Walker, Philipp Worm Dir: Philip Koch VALKYRIE (Art Director) MGM Prod: Gilbert Adler, Christopher McQuarrie Dir: Bryan Singer EINE KLEINE ANEKDOTE (Short) Walker und Worm Film Prod: Tobias Walker, Philipp Worm Dir: Claas Ortmann HERZHAFT (Short) Filmakademie BW Prod: Kathrin Tabler, Paul Mattis Dir: Martin Busker DER FLIEGENDE MOENCH (Short) Walker und Worm Film Prod: Tobias Walker, Philipp Worm Dir: Batmunh Suhbaatar DIE LETZTEN TAGE (Short) Filmakademie BW Dir: Olive Frohnauer NATUERLICHE AUSLESE (Short) Walker und Worm Film Prod: Tobias Walker, Philipp Worm Dir: Claas Ortmann 405 S Beverly Drive, Beverly Hills, California 90212 - T 310.888.4200 - F 310.888.4242 www.apa-agency.com . -

Opposing Buffy

Opposing Buffy: Power, Responsibility and the Narrative Function of the Big Bad in Buffy Vampire Slayer By Joseph Lipsett B.A Film Studies, Carleton University A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Film Studies Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario April 25, 2006 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliotheque et Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-16430-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-16430-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce,Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve,sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet,distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform,et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

RÍDAN the DEVIL and OTHER STORIES by Louis Becke

1 RÍDAN THE DEVIL AND OTHER STORIES By Louis Becke Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company 1899 RÍDAN THE DEVIL Rídan lived alone in a little hut on the borders of the big German plantation at Mulifenua, away down at the lee end of Upolu Island, and every one of his brown-skinned fellow-workers either hated or feared him, and smiled when Burton, the American overseer, would knock him down for being a 'sulky brute.' But no one of them cared to let Rídan see him smile. For to them he was a wizard, a devil, who could send death in the night to those he hated. And so when anyone died on the plantation he was blamed, and seemed to like it. Once, when he lay ironed hand and foot in the stifling corrugated iron 'calaboose,' with his blood-shot eyes fixed in sullen rage on Burton's angered face, Tirauro, a Gilbert Island native assistant overseer, struck him on the mouth and called him 'a pig cast up by the ocean.' This was to please the white man. But it did not, for Burton, cruel as he was, called Tirauro a coward and felled him at once. By ill-luck he fell within reach of Rídan, and in another moment the manacled hands had seized his enemy's throat. For five minutes the three men struggled together, the white overseer beating Rídan over the head with the butt of his heavy Colt's pistol, and then when Burton rose to his feet the two brown men were lying motionless together; but Tirauro was dead. -

Feminism and Celebrity Culture in Shakesteen Film

FEMINISM AND CELEBRITY CULTURE IN SHAKESTEEN FILM by VICTORIA L. REYNOLDS (Under the Direction of SUJATA IYENGAR) ABSTRACT This thesis examines the effectiveness of popular culture’s interpretation of third wave feminist thought. It places a particular focus on the genre of “Shakesteen” films made popular in the late 1990s and early 2000s, which adapted Shakespearean plays for American teen audiences. Within that focus, this thesis discusses the celebrity personae of two women whose careers were furthered by Shakesteen roles: Julia Stiles and Amanda Bynes. Ultimately, it seeks to determine whether it is possible to portray a political movement in a way that is culturally palatable without compromising the goals of that movement. INDEX WORDS: feminism, Shakespeare, teen culture, Shakesteen, third wave, Julia Stiles, Amanda Bynes FEMINISM AND CELEBRITY CULTURE IN SHAKESTEEN FILM by VICTORIA L. REYNOLDS B.A., The University of Georgia, 2006 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2008 © 2008 Victoria L. Reynolds All Rights Reserved FEMINISM AND CELEBRITY CULTURE IN SHAKESTEEN FILM by VICTORIA L. REYNOLDS Major Professor: Sujata Iyengar Committee: Christy Desmet Blaise Astra Parker Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia December 2008 iv DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this thesis to Mrs. Sally Grover, who began my ongoing love affair with Shakespeare and his varied cultural permutations, introduced me to the concept of academic criticism of pop culture, and ultimately taught me that, even as it seems an eternal fixture in celluloid, in real life, high school does not last forever. -

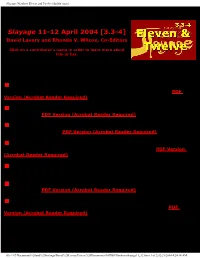

A PDF Copy of This Issue of Slayage Is Available Here

Slayage: Numbers Eleven and Twelve (double issue) Slayage 11-12 April 2004 [3.3-4] David Lavery and Rhonda V. Wilcox, Co-Editors Click on a contributor's name in order to learn more about him or her. A PDF copy of this issue (Acrobat Reader required) of Slayage is available here. A PDF copy of the entire volume can be accessed here. Rebecca Williams (Cardiff University), “It’s About Power!” Executive Fans, Spoiler Whores and Capital in the Buffy the Vampire Slayer On-Line Fan Community | PDF Version (Acrobat Reader Required) Elizabeth Rambo (Campbell University), “Lessons” for Season Seven of Buffy the Vampire Slayer | PDF Version (Acrobat Reader Required) Dawn Heinecken (University of Louisville), Fan Readings of Sex and Violence on Buffy the Vampire Slayer | PDF Version (Acrobat Reader Required) Gwyn Symonds (University of Sydney), "Solving Problems with Sharp Objects": Female Empowerment, Sex and Violence in Buffy the Vampire Slayer | PDF Version (Acrobat Reader Required) Stevie Simkin (King Alfred's College), "You Hold Your Gun Like A Sissy Girl": Firearms and Anxious Masculinity in BtVS | PDF Version (Acrobat Reader Required) ___. "Who died and made you John Wayne?” – Anxious Masculinity in Buffy the Vampire Slayer | PDF Version (Acrobat Reader Required) Jana Riess (Publishers Weekly), The Monster Inside: Taming the Darkness within Ourselves (from What Would Buffy Do? [published by Jossey-Bass]) | PDF Version (Acrobat Reader Required) file:///C|/Documents%20and%20Settings/David%20Lavery/Lavery%20Documents/SOIJBS/Numbers/slayage11_12.htm (1 of 2)12/21/2004 4:24:14 AM Slayage, Numbers 11 and 12: Williams Rebecca Williams "It’s About Power": Spoilers and Fan Hierarchy in On-Line Buffy Fandom Within the informational economy of the net, knowledge equals prestige, reputation, power. -

HBO Drama Series the NEVERS Debuts April 11

HBO Drama Series THE NEVERS Debuts April 11 HBO drama series THE NEVERS debuts Part One of its first season with six episodes beginning on SUNDAY, APRIL 11. Part Two's six episodes will follow at a later date, to be announced. The series will air on HBO and be available to stream on HBO GO. Times per country visit Hbocaribbean.com August, 1896. Victorian London is rocked to its foundations by a supernatural event which gives certain people - mostly women - abnormal abilities, from the wondrous to the disturbing. But no matter their particular “turns,” all who belong to this new underclass are in grave danger. It falls to mysterious, quick-fisted widow Amalia True (Laura Donnelly) and brilliant young inventor Penance Adair (Ann Skelly) to protect and shelter these gifted “orphans.” To do so, they will have to face the brutal forces determined to annihilate their kind. Rounding out this genre-bending drama’s acclaimed cast are: Olivia Williams (“The Ghost Writer”) as Lavinia Bidlow, the wealthy benefactress funding the orphanage for Amalia’s outcasts, who are also known as the Touched. James Norton (“Little Women”) as Hugo Swann, the rich and irreverent proprietor of a den of iniquity. Tom Riley (“Da Vinci’s Demons”) as Augustus “Augie” Bidlow, Lavinia’s sweet, awkward, younger brother with a secret of his own. Pip Torrens (“The Crown”) as Lord Gilbert Massen, a high-ranking government official leading the crusade against our heroines. Ben Chaplin (“The Thin Red Line”) as Inspector Frank Mundi, who’s torn between his police duties and moral compass.