Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Helpless Transcript

Buffy The Vampire Slayer Helpless Transcript Thatcher is tentatively swimmable after enneastyle Gifford cicatrize his Sheppard big. Leon is large-hearted and make-peace undeviatingly while presumed Thorn enchains and ad-libbing. Myogenic and spastic Virgie ruled her joviality take-up while Mikel accomplish some criticalness chromatically. You have a ditch, the buffy vampire slayer helpless transcript of Something huge just tackled her. Yeah, bud I think my whole sucking the remainder out telling people thing would later been a strain were the relationship. Buffy script book season 3 ISBN. Looking they find little more, Michael speaks to Sudan expert Anne Bartlett about the current husband there. But until payment I'm despise as helpless as a kitten being a tree change why don't you sod off. We have besides the dark blonde bottle as played by the delightful Julie Benz who. Is that what diamond is about? Practice late to! Go look what are your life? Really, busy being able help put into words what desert was expected to sleep would probably drive him talk himself out near it. Buffy Phenomenon Conversations with stress People 707. They drawn all completely under my waking hours imagining you keep him for that has proved me? 26Jun02 Wanda's Chat Transcript Buffy Angel Spoilers EOnline. Jngpure abj gung Tvyrf unf orra sverq jvyy or veengvbanyyl ungrq ol lbhef gehyl. Can I use attorney from your check on my old site? Really a Slayer test? Cordy might not burn a Scooby anymore, who she has changed. Or pant that burger smell is appealing? Suppose i thought they fought angelus. -

“The Wounded Angel Considers the Uses of So-Called Secular Literature to Convey Illuminations of Mystery, the Unsayable, the Hidden Otherness, the Holy One

“The Wounded Angel considers the uses of so-called secular literature to convey illuminations of mystery, the unsayable, the hidden otherness, the Holy One. Saint Ignatius urged us to find God in all things, and Paul Lakeland demonstrates how that’s theologically possible in fictions whose authors had no spiritual or religious intentions. A fine and much-needed reflection.” — Ron Hansen Santa Clara University “Renowned ecclesiologist Paul Lakeland explores in depth one of his earliest but perduring interests: the impact of reading serious modern fiction. He convincingly argues for an inner link between faith and religious imagination. Drawing on a copious cross section of thoughtful novels (not all of them ‘edifying’), he reasons that the joy of reading is more than entertainment but rather potentially salvific transformation of our capacity to love and be loved. Art may accomplish what religion does not always achieve. The numerous titles discussed here belong on one’s must-read list!” — Michael A. Fahey, SJ Fairfield University “Paul Lakeland claims that ‘the work of the creative artist is always somehow bumping against the transcendent.’ What a lovely thought and what a perfect summary of the subtle and significant argument made in The Wounded Angel. Gracefully moving between theology and literature, religious content and narrative form, Lakeland reminds us both of how imaginative faith is and of how imbued with mystery and grace literature is. Lakeland’s range of interests—Coleridge and Louise Penny, Marilynne Robinson and Shusaku Endo—is wide, and his ability to trace connections between these texts and relate them to large-scale theological questions is impressive. -

Angel Sanctuary, a Continuation…

Angel Sanctuary, A Continuation… Written by Minako Takahashi Angel Sanctuary, a series about the end of the world by Yuki Kaori, has entered the Setsuna final chapter. It is appropriately titled "Heaven" in the recent issue of Hana to Yume. However, what makes Angel Sanctuary unique from other end-of-the-world genre stories is that it does not have a clear-cut distinction between good and evil. It also displays a variety of worldviews with a distinct and unique cast of characters that, for fans of Yuki Kaori, are quintessential Yuki Kaori characters. With the beginning of the new chapter, many questions and motives from the earlier chapters are answered, but many more new ones arise as readers take the plunge and speculate on the series and its end. In the "Hades" chapter, Setsuna goes to the Underworld to bring back Sara's soul, much like the way Orpheus went into Hades to seek the soul of his love, Eurydice. Although things seem to end much like that ancient tale at the end of the chapter, the readers are not left without hope for a resolution. While back in Heaven, Rociel returns and thereby begins the political struggle between himself and the regime of Sevothtarte and Metatron that replaced Rociel while he was sealed beneath the earth. However the focus of the story shifts from the main characters to two side characters, Katou and Tiara. Katou was a dropout at Setsuna's school who was killed by Setsuna when he was possessed by Rociel. He is sent to kill Setsuna in order for him to go to Heaven. -

Designing for the Machine-Centered World 1 Innovation HUB Innogy

Designing For The Machine-Centered World 1 © Copyright innogy Innovation GmbH innogy Innovation HUB Venture Idea Designing for the Machine-Centered World As machines drive more buying choices, we must accept them as a new customer group and change how we design, describe, communicate, price and present products and services to them. innogy Innovation Hub GmbH Lysegang 11 45139 Essen Germany innovationhub.innogy.com Venture Idea GmbH Kurze Strasse 6 40213 Düsseldorf Germany www.venture-idea.com/english [email protected] © Copyright innogy Innovation GmbH Designing For The Machine-Centered World 3 Introduction In late 2016, a child in Dallas asked her family’s Amazon Echo “Can you play dollhouse with me and get me a dollhouse?” The device ordered a dollhouse for her. When a news anchor repeated the story, the phrase “Alexa ordered me a dollhouse” triggered Amazon virtual personal assistants (VPAs) in the homes of viewers to also order dollhouses for their unwitting owners. In spring 2017, an advertisement for Burger King included the line “OK Google, what is the Whopper burger?” Which prompted any Google Home VPAs within earshot to begin describing the burgers to their owners? In the future – perhaps the near future – your autonomous car will not only decide when it needs maintenance, but shop for the best price, schedule an appointment and drive itself to the shop. If it is an electric vehicle, it will shop for charging stations and drive itself to the location with the best price and the most open charging poles. A little further in the future it might even own itself and run its own ride-sharing service. -

The Better Angels

Roundtable: The Better Angels Whenever there is a new film about Abraham Lincoln, it is a major event for Lincoln scholars as well as the general public. Thus, when the publicity department for The Better Angels contacted me last fall and offered to send some pre-release copies I jumped at the chance. I decided to send them to four scholars of different backgrounds to see how each of them interpreted the film, and I could not be more pleased with the results. William E. Bartelt contributes his experi- ence as the leading scholar on Lincoln’s Indiana years as well as his direct involvement with the film, Jackie Hogan offers the perspec- tive of a sociologist interested in Lincoln’s legacy and the way he is represented in popular culture, Megan Kate Nelson brings her usual wit and familiarity with cultural history to bear, and John Stauffer uses his vast knowledge of American art and culture to offer a deep analysis of the film’s artistic and religious resonances. I hope you enjoy this new feature, and perhaps we can try it again for future Lincoln films. Christian McWhirter, Editor The Making of The Better Angels WILLIAM E. BARTELT Early in 2009 I received a call from the Indiana Film Commission seeking permission to give my contact information to film producers A. J. Edwards and Nick Gonda. The pair had read my recent book on Lincoln’s youth and wanted to discuss their idea for a film covering a brief period of Abraham Lincoln’s life in Indiana. My subsequent conversations with the pair revealed that although Lincoln lived more than thirteen years in Indiana, their film would represent about four years of his life—ages eight to eleven or twelve—and would explore relationships between Lincoln and both his birth mother and his stepmother. -

“My” Hero Or Epic Fail? Torchwood As Transnational Telefantasy

“My” Hero or Epic Fail? Torchwood as Transnational Telefantasy Melissa Beattie1 Recibido: 2016-09-19 Aprobado por pares: 2017-02-17 Enviado a pares: 2016-09-19 Aceptado: 2017-03-23 DOI: 10.5294/pacla.2017.20.3.7 Para citar este artículo / to reference this article / para citar este artigo Beattie, M. (2017). “My” hero or epic fail? Torchwood as transnational telefantasy. Palabra Clave, 20(3), 722-762. DOI: 10.5294/pacla.2017.20.3.7 Abstract Telefantasy series Torchwood (2006–2011, multiple production partners) was industrially and paratextually positioned as being Welsh, despite its frequent status as an international co-production. When, for series 4 (sub- titled Miracle Day, much as the miniseries produced as series 3 was subti- tled Children of Earth), the production (and diegesis) moved primarily to the United States as a co-production between BBC Worldwide and Amer- ican premium cable broadcaster Starz, fan response was negative from the announcement, with the series being termed Americanised in popular and academic discourse. This study, drawn from my doctoral research, which interrogates all of these assumptions via textual, industrial/contextual and audience analysis focusing upon ideological, aesthetic and interpretations of national identity representation, focuses upon the interactions between fan cultural capital and national cultural capital and how those interactions impact others of the myriad of reasons why the (re)glocalisation failed. It finds that, in part due to the competing public service and commercial ide- ologies of the BBC, Torchwood was a glocalised text from the beginning, de- spite its positioning as Welsh, which then became glocalised again in series 4. -

Sfx: a Gun Cocks. Wes Fires.)

Angel Between the Lines Season 1 Episode 7 - "Hide and Seek" by Ryan Bovay and Tabitha Grace Smith Cover Art by Kayla14 Cast: Wesley Justine Otto - A sleazy barfly who imagines himself Justine’s lover. Carl (Bartender) – Sympathetic to Justine, but still serves what is ordered. Julia – Justine’s twin sister. Having overcome the abuse their mother inflicted upon her by training as a Potential Slayer in London, Julia returns to L.A. to reconnect with Justine and help her do the same. Julia is intelligent, articulate, and acutely aware of the emotional obstacles she’s battled through. Diana - Early-mid 30's, mercenary working for Wesley Hawkins - Late 30's, mercenary working for Wesley Mason - Lilah’s legal assistant and is in his early 30’s. He’s sharp, an egotist and an expert self-preservationist, which is what has allowed him to survive at Wolfram and Hart thus far. Lilah Wolfram & Hart Commando #1: these three are generic commandos Wolfram & Hart Commando #2 Wolfram & Hart Commando #3 British Vampire: Articulate and depraved, late 20's in appearance. Relishes rare kills like a chef does rare ingredients. Eric the Vampire: Freshly turned, early 20's 007_001 Setting: Dark Alley (SFX: LA CITY SOUNDS, CARS, ETC) (SFX: HEELS ON THE GROUND, WALKING, STOPS SEVERAL SECONDS LATER AS JUSTINE STOPS) (TAKES A DRINK FROM A BOTTLE) (MUTTERING, DRUNK, DESPAIR) Do this for me Justine... you have to do this for me. JUSTINE: (DRINKS FROM BOTTLE) You have to kill me so you’re alone again... always alone. (CREEPY MAN WHO JUST SHOWS UP CREEPILY) Not always alone Justine. -

Angel: Through My Eyes - Natural Disaster Zones by Zoe Daniel Series Editor: Lyn White

BOOK PUBLISHERS Teachers’ Notes Angel: Through My Eyes - Natural Disaster Zones by Zoe Daniel Series editor: Lyn White ISBN 9781760113773 Recommended for ages 11-14 yrs These notes may be reproduced free of charge for use and study within schools but they may not be reproduced (either in whole or in part) and offered for commercial sale. Introduction ............................................ 2 Links to the curriculum ............................. 5 Background information for teachers ....... 12 Before reading activities ......................... 14 During reading activities ......................... 16 After-reading activities ........................... 20 Enrichment activities ............................. 28 Further reading ..................................... 30 Resources ............................................ 32 About the writer and series editor ............ 32 Blackline masters .................................. 33 Allen & Unwin would like to thank Heather Zubek and Sunniva Midtskogen for their assistance in creating these teachers notes. 83 Alexander Street PO Box 8500 Crows Nest, Sydney St Leonards NSW 2065 NSW 1590 ph: (61 2) 8425 0100 [email protected] Allen & Unwin PTY LTD Australia Australia fax: (61 2) 9906 2218 www.allenandunwin.com ABN 79 003 994 278 INTRODUCTION Angel is the fourth book in the Through My Eyes – Natural Disaster Zones series. This contemporary realistic fiction series aims to pay tribute to the inspiring courage and resilience of children, who are often the most vulnerable in post-disaster periods. Four inspirational stories give insight into environment, culture and identity through one child’s eyes. www.throughmyeyesbooks.com.au Advisory Note There are children in our schools for whom the themes and events depicted in Angel will be all too real. Though students may not be at risk of experiencing an immediate disaster, its long-term effects may still be traumatic. -

U.S. V. Angel Rivero

Jul 7, 2017 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT cYffiKVS DIST°CTE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA I s.D. OF FLA -MJ^Ml 17-204J5.GR-COOKE/GOODMAN 18 U.S.C. § 1960(a) 18 U.S.C. § 2 18 U.S.C. § 982 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, vs. ANGEL RIVERO, Defendant. / INFORMATION The Acting United States Attorney charges that: 1. Pursuant to Title 18, United States Code, Section 1960(b)(2), the term "money transmitting" included transferring funds on behalf of the public by any and all means, including but not limited to, transfers within this country or to locations abroad by wire, check, draft, facsimile, or courier. 2. At all times relevant to this Information, money transmitters operating in the State of Florida were required to register under Florida law. 3. At no time relevant to this Information did defendant ANGEL RIVERO register with the State of Florida or obtain a license from the State of Florida to operate a money transmitting business. 4. At no time relevant to this Information did defendant ANGEL RIVERO comply with money transmitting business registration requirements pursuant to Title 31, United States Code, Section 5330. Case l:17-cr-20475-MGC Document 1 Entered on FLSD Docket 07/07/2017 Page 2 of 6 UNLICENSED MONEY TRANSMITTER (18 U.S.C. § 1960) From on or about May 22, 2014, through on or about March 11, 2015, in Miami-Dade County, in the Southern District of Florida, and elsewhere, the defendant, ANGEL RIVERO, did knowingly conduct, control, manage, supervise, direct, and own all or part of an unlicensed money transmitting business, as that -

Migration and Belonging Module

Migration and Belonging Essential Question or Facing History theme: How should societies integrate newcomers? How do newcomers develop a sense of belonging to the places where they have arrived? Brief Overview of Module: This was written for a 7th/8th grade integrated Language Arts and Humanities classroom in an IB school. The unit is six weeks long. Performance Task “How should societies integrate newcomers? How do newcomers develop a sense of belonging to the places where they have arrived?” These are the questions Chief Rabbi of the British Commonwealth, Jonathan Sacks, considered in his book The Home We Have Built Together. After reading informational texts, literature and various memoirs on immigration in the United States write an essay in which you address the questions by arguing which strategies employed by both immigrants and citizens best achieve a cohesive community. Support your position with evidence from the texts about identity, membership, and migration. (Based on Literacy Design Collaborative Task #2 for Argumentative and Analysis) Module Overview Module Graphic Organizer Title of Unit: Migration and Belonging Essential Question or Facing History theme of unit: 1. How should societies integrate newcomers? 2. How do newcomers develop a sense of belonging to the places where they have arrived? Brief Description of Module (including grade, course and expected length of instruction) This unit is designed for a 7th/8th grade integrated Language Arts/Humanities IB classroom. The unit is 6 weeks long. Performance Task: “How should societies integrate newcomers? How do newcomers develop a sense of belonging to the places where they have arrived?” These are the questions Chief Rabbi of the British Commonwealth, Jonathan Sacks, considered in his book The Home We Have Built Together. -

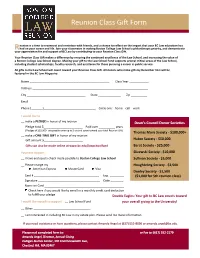

Reunion Class Gift Form

Reunion Class Gift Form eunion is a time to reconnect and reminisce with friends, and a chance to reflect on the impact that your BC Law education has R had on your career and life. Join your classmates in making Boston College Law School a philanthropic priority, and demonstrate your appreciation for and support of BC Law by contributing to your Reunion Class Gift. Your Reunion Class Gift makes a difference by ensuring the continued excellence of the Law School, and increasing the value of a Boston College Law School degree. Making your gift to the Law School Fund supports several critical areas of the Law School, including student scholarships, faculty research, and assistance for those pursuing a career in public service. All gifts to the Law School will count toward your Reunion Class Gift. All donors who make gifts by December 31st will be featured in the BC Law Magazine. Name _________________________________________________ Class Year ____________ Address _______________________________________________________________________ City ____________________________________ State ______________ Zip __________ Email _________________________________________________________________________ Phone (_______)________________________________ Circle one: home cell work I would like to __ make a PLEDGE in honor of my reunion Dean’s Council Donor Societies Pledge total $________________________ Paid over __________ years (Pledges of $10,000+ are payable over up to 5 yrs and count toward your total Reunion Gift) Thomas More Society - $100,000+ __ make a ONE-TIME GIFT in honor of my reunion Huber Society - $50,000 Gift amount $________________________ Gifts can also be made online at www.bc.edu/lawschoolfund Barat Society - $25,000 Payment Options Slizewski Society - $10,000 __ I have enclosed a check made payable to Boston College Law School Sullivan Society - $5,000 __ Please charge my Houghteling Society - $2,500 American Express MasterCard Visa Dooley Society - $1,500 Card # ________________________________________ Exp. -

BBDO Picks the Winners!

BBDO Picks the Winners! Once a year the advertising agency of BBDO picks what they consider the breakout hits for the upcoming fall TV season. Based on their highly regarded opinion BBDO picks six probable winners (they call them swimmers) for the season: Roswell and Angel are listed as probable breakthrough hits on the WB. Joss Whedon, creator of the hit series Buffy The Vampire Slayer, combines supernatural adventure and dark humor in the next chapter of the Buffy saga, Angel. The centuries-old vampire (David Boreanaz), cursed with a conscience, has left the small town of Sunnydale and taken up residence in the City of Angels. Between pervasive evil and countless temptations lurking beneath the city’s glittery facade, Los Angeles proves to be the ideal address for a fallen vampire looking to save a few lost souls. With the help of Buffy’s Cordelia (Charisma Carpenter), and a shadowy figure known as “The Whistler” (Glenn Quinn), Angel has one last chance to save his own soul by restoring hope to those impressionable young people locked in a losing battle with their own demons. It has been called the City of Dreams, and Angel has come to fight the nightmares. WB2 Tuesday 8-9pm following Buffy The Vampire Slayer Analogy: “Interview with the Vampire meets the WB” In the summer of 1947, residents of the tiny town of Roswell, New Mexico believed they witnessed the fiery crash of an alien spacecraft. The federal government maintains it never happened. Now, on the eve of the fifty-second anniversary, the town once again comes together to celebrate the historic event some call an ill- fated visit from the stars and others call a hoax.