Slayage, Number 16

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hamilton County Criminal Court 9/29/2021 Page No: 1 Trial Docket Trial Date: 09/29/2021 Division: 1 Judge: STEELMAN, BARRY A

CJUSHAND Hamilton County Criminal Court 9/29/2021 Page No: 1 Trial Docket Trial Date: 09/29/2021 Division: 1 Judge: STEELMAN, BARRY A. State vs. ATKINS , DEDRIC LAMONT aka ATKINS, DEDRICK Silverdale AGGRAVATED ARSON Counts: 1 Thru 1 TCA: 39140302 TIBRS: VANDALISM Counts: 2 Thru 2 TCA: 39140408 TIBRS: 290 Docket #: 310525 Bond Amt: $0.00 Attorney: PERRY, JAY (P.D.) District Attorney: ORTWEIN, FREDERICK LEE Bonding Co.: Order of Court: Active Bond Date: NVC PP Number Times: Case Type: Indictment Filing Date: 9/30/2020 Number of Trial Docket Appearances: 8 Amount Owed on this Case: $0.00 Total Amounts Owed: $765.00 7/21/2021 - PASSED SEPTEMBER 29 2021 FOR SETTLEMENT #1 6/23/2021 - FORMAL ORDER THAT THE DEFENDANT BE REFERRED TO THE MIDDLE TENNESSEE MENTAL HEALTH INSTITUTE, FSP FOR FORENSIC EVALUATION. THE PREVIOUS ORDER REGARDING MOCCASIN BEND HEALTH INSTITURE IS HEREBY RESCINDED. #1 6/22/2021 - FORMAL ORDER THAT THE DEFENDANT BE REFERRED TO THE MOCCASIN BEND HEALTH INSTITURE FOR A MAXIMUM OF 30 DAYS FOR FORENSIC EVALUATION. #1 5/26/2021 - ORAL MOTION FOR FORENSIC EVALUATION HEARD AND SUSTAINED - PASSED JULY 21, 2021 FOR SETTLEMENT #1 5/26/2021 - FORMAL ORDER ENTERED DIRECTING FORENSIC EVALUATION #1 State vs. ATKINS , DEDRIC LAMONT aka ATKINS, DEDRICK Silverdale DOMESTIC AGGRAVATED ASSAULT Counts: 1 Thru 1 TCA: 39130102 TIBRS: 13A Docket #: 310526 Bond Amt: $0.00 Attorney: PERRY, JAY (P.D.) District Attorney: Bonding Co.: Order of Court: Active Bond Date: NVC PP Number Times: Case Type: Indictment Filing Date: 9/30/2020 Number of Trial Docket Appearances: 8 Amount Owed on this Case: $0.00 Total Amounts Owed: $765.00 7/21/2021 - PASSED SEPTEMBER 29 2021 FOR SETTLEMENT #1 6/23/2021 - FORMAL ORDER THAT THE DEFENDANT BE REFERRED TO THE MIDDLE TENNESSEE MENTAL HEALTH INSTITUTE, FSP FOR FORENSIC EVALUATION. -

Scheherazade

SCHEHERAZADE The MPC Literary Magazine Issue 9 Scheherazade Issue 9 Managing Editors Windsor Buzza Gunnar Cumming Readers Jeff Barnard, Michael Beck, Emilie Bufford, Claire Chandler, Angel Chenevert, Skylen Fail, Shay Golub, Robin Jepsen, Davis Mendez Faculty Advisor Henry Marchand Special Thanks Michele Brock Diane Boynton Keith Eubanks Michelle Morneau Lisa Ziska-Marchand i Submissions Scheherazade considers submissions of poetry, short fiction, creative nonfiction, novel excerpts, creative nonfiction book excerpts, graphic art, and photography from students of Monterey Peninsula College. To submit your own original creative work, please follow the instructions for uploading at: http://www.mpc.edu/scheherazade-submission There are no limitations on style or subject matter; bilingual submissions are welcome if the writer can provide equally accomplished work in both languages. Please do not include your name or page numbers in the work. The magazine is published in the spring semester annually; submissions are accepted year-round. Scheherazade is available in print form at the MPC library, area public libraries, Bookbuyers on Lighthouse Avenue in Monterey, The Friends of the Marina Library Community Bookstore on Reservation Road in Marina, and elsewhere. The magazine is also published online at mpc.edu/scheherazade ii Contents Issue 9 Spring 2019 Cover Art: Grandfather’s Walnut Tree, by Windsor Buzza Short Fiction Thank You Cards, by Cheryl Ku ................................................................... 1 The Bureau of Ungentlemanly Warfare, by Windsor Buzza ......... 18 Springtime in Ireland, by Rawan Elyas .................................................. 35 The Divine Wind of Midnight, by Clark Coleman .............................. 40 Westley, by Alivia Peters ............................................................................. 65 The Headmaster, by Windsor Buzza ...................................................... 74 Memoir Roller Derby Dreams, by Audrey Word ................................................ -

Folsom Telegraph

THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 20, 2020 Kitchen & Bath Top Five Newspaper Remodeling CNPA California Journalism Awards Painting THE FOLSOM Cabinets Counters Flooring Remodeling Jobs completed before April 1, 2020 * only while openings last * not to be combined with any other offer Your community news by a dam site since 1856 Serving the communities of Folsom and El Dorado Hills 916.774.6416 www.PerrymanPainting.com FOLSOMTELEGRAPH.COM Lic # 948889 (C33 & B) Exoneration, new arrest in 1985 EDH murder case BY BILL SULLIVAN The 1985 case went “This is the first case in occurred on July 7, 1985. OF THE FOLSOM TELEGRAPH unsolved for 14 years before California and only the For all these years, investigators said DNA second in this country Davis has been behind Since his conviction, evidence and an incrim- where investigative genetic bars awaiting retrial, for Ricky Davis continued inating statement by a genealogy has not only led a crime he didn’t commit. to plead his innocence resident of the home tied to the freeing on an individ- El Dorado Superior Court in an El Dorado Hills Davis to the slaying back in ual from prison for a crime Judge Kenneth Mele- murder that took place 35 November of 1999. He was he did not commit, but the kian ended that when he years ago. Last Thursday, then sentenced in 2005 to identification of the true threw out his second-de- 54-year-old Davis walked 16 years-to-life, accused of source,” said Sacramento gree murder conviction in out of El Dorado County stabbing Hylton 29 times County District Attorney the emotional court hear- Superior Court a free man in what was described as a Anne Marie Schubert. -

“The Wounded Angel Considers the Uses of So-Called Secular Literature to Convey Illuminations of Mystery, the Unsayable, the Hidden Otherness, the Holy One

“The Wounded Angel considers the uses of so-called secular literature to convey illuminations of mystery, the unsayable, the hidden otherness, the Holy One. Saint Ignatius urged us to find God in all things, and Paul Lakeland demonstrates how that’s theologically possible in fictions whose authors had no spiritual or religious intentions. A fine and much-needed reflection.” — Ron Hansen Santa Clara University “Renowned ecclesiologist Paul Lakeland explores in depth one of his earliest but perduring interests: the impact of reading serious modern fiction. He convincingly argues for an inner link between faith and religious imagination. Drawing on a copious cross section of thoughtful novels (not all of them ‘edifying’), he reasons that the joy of reading is more than entertainment but rather potentially salvific transformation of our capacity to love and be loved. Art may accomplish what religion does not always achieve. The numerous titles discussed here belong on one’s must-read list!” — Michael A. Fahey, SJ Fairfield University “Paul Lakeland claims that ‘the work of the creative artist is always somehow bumping against the transcendent.’ What a lovely thought and what a perfect summary of the subtle and significant argument made in The Wounded Angel. Gracefully moving between theology and literature, religious content and narrative form, Lakeland reminds us both of how imaginative faith is and of how imbued with mystery and grace literature is. Lakeland’s range of interests—Coleridge and Louise Penny, Marilynne Robinson and Shusaku Endo—is wide, and his ability to trace connections between these texts and relate them to large-scale theological questions is impressive. -

Angel Sanctuary, a Continuation…

Angel Sanctuary, A Continuation… Written by Minako Takahashi Angel Sanctuary, a series about the end of the world by Yuki Kaori, has entered the Setsuna final chapter. It is appropriately titled "Heaven" in the recent issue of Hana to Yume. However, what makes Angel Sanctuary unique from other end-of-the-world genre stories is that it does not have a clear-cut distinction between good and evil. It also displays a variety of worldviews with a distinct and unique cast of characters that, for fans of Yuki Kaori, are quintessential Yuki Kaori characters. With the beginning of the new chapter, many questions and motives from the earlier chapters are answered, but many more new ones arise as readers take the plunge and speculate on the series and its end. In the "Hades" chapter, Setsuna goes to the Underworld to bring back Sara's soul, much like the way Orpheus went into Hades to seek the soul of his love, Eurydice. Although things seem to end much like that ancient tale at the end of the chapter, the readers are not left without hope for a resolution. While back in Heaven, Rociel returns and thereby begins the political struggle between himself and the regime of Sevothtarte and Metatron that replaced Rociel while he was sealed beneath the earth. However the focus of the story shifts from the main characters to two side characters, Katou and Tiara. Katou was a dropout at Setsuna's school who was killed by Setsuna when he was possessed by Rociel. He is sent to kill Setsuna in order for him to go to Heaven. -

Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic

Please do not remove this page Giving Evil a Name: Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic Croft, Janet Brennan https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643454990004646?l#13643522530004646 Croft, J. B. (2015). Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic. Slayage: The Journal of the Joss Whedon Studies Association, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.7282/T3FF3V1J This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/10/02 09:39:58 -0400 Janet Brennan Croft1 Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic “It’s about power. Who’s got it. Who knows how to use it.” (“Lessons” 7.1) “I would suggest, then, that the monsters are not an inexplicable blunder of taste; they are essential, fundamentally allied to the underlying ideas of the poem …” (J.R.R. Tolkien, “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics”) Introduction: Names and Blood in the Buffyverse [1] In Joss Whedon’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003) and Angel (1999- 2004), words are not something to be taken lightly. A word read out of place can set a book on fire (“Superstar” 4.17) or send a person to a hell dimension (“Belonging” A2.19); a poorly performed spell can turn mortal enemies into soppy lovebirds (“Something Blue” 4.9); a word in a prophecy might mean “to live” or “to die” or both (“To Shanshu in L.A.” A1.22). -

Sfx: a Gun Cocks. Wes Fires.)

Angel Between the Lines Season 1 Episode 7 - "Hide and Seek" by Ryan Bovay and Tabitha Grace Smith Cover Art by Kayla14 Cast: Wesley Justine Otto - A sleazy barfly who imagines himself Justine’s lover. Carl (Bartender) – Sympathetic to Justine, but still serves what is ordered. Julia – Justine’s twin sister. Having overcome the abuse their mother inflicted upon her by training as a Potential Slayer in London, Julia returns to L.A. to reconnect with Justine and help her do the same. Julia is intelligent, articulate, and acutely aware of the emotional obstacles she’s battled through. Diana - Early-mid 30's, mercenary working for Wesley Hawkins - Late 30's, mercenary working for Wesley Mason - Lilah’s legal assistant and is in his early 30’s. He’s sharp, an egotist and an expert self-preservationist, which is what has allowed him to survive at Wolfram and Hart thus far. Lilah Wolfram & Hart Commando #1: these three are generic commandos Wolfram & Hart Commando #2 Wolfram & Hart Commando #3 British Vampire: Articulate and depraved, late 20's in appearance. Relishes rare kills like a chef does rare ingredients. Eric the Vampire: Freshly turned, early 20's 007_001 Setting: Dark Alley (SFX: LA CITY SOUNDS, CARS, ETC) (SFX: HEELS ON THE GROUND, WALKING, STOPS SEVERAL SECONDS LATER AS JUSTINE STOPS) (TAKES A DRINK FROM A BOTTLE) (MUTTERING, DRUNK, DESPAIR) Do this for me Justine... you have to do this for me. JUSTINE: (DRINKS FROM BOTTLE) You have to kill me so you’re alone again... always alone. (CREEPY MAN WHO JUST SHOWS UP CREEPILY) Not always alone Justine. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

Angel: Through My Eyes - Natural Disaster Zones by Zoe Daniel Series Editor: Lyn White

BOOK PUBLISHERS Teachers’ Notes Angel: Through My Eyes - Natural Disaster Zones by Zoe Daniel Series editor: Lyn White ISBN 9781760113773 Recommended for ages 11-14 yrs These notes may be reproduced free of charge for use and study within schools but they may not be reproduced (either in whole or in part) and offered for commercial sale. Introduction ............................................ 2 Links to the curriculum ............................. 5 Background information for teachers ....... 12 Before reading activities ......................... 14 During reading activities ......................... 16 After-reading activities ........................... 20 Enrichment activities ............................. 28 Further reading ..................................... 30 Resources ............................................ 32 About the writer and series editor ............ 32 Blackline masters .................................. 33 Allen & Unwin would like to thank Heather Zubek and Sunniva Midtskogen for their assistance in creating these teachers notes. 83 Alexander Street PO Box 8500 Crows Nest, Sydney St Leonards NSW 2065 NSW 1590 ph: (61 2) 8425 0100 [email protected] Allen & Unwin PTY LTD Australia Australia fax: (61 2) 9906 2218 www.allenandunwin.com ABN 79 003 994 278 INTRODUCTION Angel is the fourth book in the Through My Eyes – Natural Disaster Zones series. This contemporary realistic fiction series aims to pay tribute to the inspiring courage and resilience of children, who are often the most vulnerable in post-disaster periods. Four inspirational stories give insight into environment, culture and identity through one child’s eyes. www.throughmyeyesbooks.com.au Advisory Note There are children in our schools for whom the themes and events depicted in Angel will be all too real. Though students may not be at risk of experiencing an immediate disaster, its long-term effects may still be traumatic. -

U.S. V. Angel Rivero

Jul 7, 2017 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT cYffiKVS DIST°CTE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA I s.D. OF FLA -MJ^Ml 17-204J5.GR-COOKE/GOODMAN 18 U.S.C. § 1960(a) 18 U.S.C. § 2 18 U.S.C. § 982 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, vs. ANGEL RIVERO, Defendant. / INFORMATION The Acting United States Attorney charges that: 1. Pursuant to Title 18, United States Code, Section 1960(b)(2), the term "money transmitting" included transferring funds on behalf of the public by any and all means, including but not limited to, transfers within this country or to locations abroad by wire, check, draft, facsimile, or courier. 2. At all times relevant to this Information, money transmitters operating in the State of Florida were required to register under Florida law. 3. At no time relevant to this Information did defendant ANGEL RIVERO register with the State of Florida or obtain a license from the State of Florida to operate a money transmitting business. 4. At no time relevant to this Information did defendant ANGEL RIVERO comply with money transmitting business registration requirements pursuant to Title 31, United States Code, Section 5330. Case l:17-cr-20475-MGC Document 1 Entered on FLSD Docket 07/07/2017 Page 2 of 6 UNLICENSED MONEY TRANSMITTER (18 U.S.C. § 1960) From on or about May 22, 2014, through on or about March 11, 2015, in Miami-Dade County, in the Southern District of Florida, and elsewhere, the defendant, ANGEL RIVERO, did knowingly conduct, control, manage, supervise, direct, and own all or part of an unlicensed money transmitting business, as that -

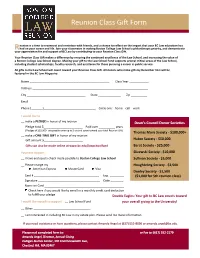

Reunion Class Gift Form

Reunion Class Gift Form eunion is a time to reconnect and reminisce with friends, and a chance to reflect on the impact that your BC Law education has R had on your career and life. Join your classmates in making Boston College Law School a philanthropic priority, and demonstrate your appreciation for and support of BC Law by contributing to your Reunion Class Gift. Your Reunion Class Gift makes a difference by ensuring the continued excellence of the Law School, and increasing the value of a Boston College Law School degree. Making your gift to the Law School Fund supports several critical areas of the Law School, including student scholarships, faculty research, and assistance for those pursuing a career in public service. All gifts to the Law School will count toward your Reunion Class Gift. All donors who make gifts by December 31st will be featured in the BC Law Magazine. Name _________________________________________________ Class Year ____________ Address _______________________________________________________________________ City ____________________________________ State ______________ Zip __________ Email _________________________________________________________________________ Phone (_______)________________________________ Circle one: home cell work I would like to __ make a PLEDGE in honor of my reunion Dean’s Council Donor Societies Pledge total $________________________ Paid over __________ years (Pledges of $10,000+ are payable over up to 5 yrs and count toward your total Reunion Gift) Thomas More Society - $100,000+ __ make a ONE-TIME GIFT in honor of my reunion Huber Society - $50,000 Gift amount $________________________ Gifts can also be made online at www.bc.edu/lawschoolfund Barat Society - $25,000 Payment Options Slizewski Society - $10,000 __ I have enclosed a check made payable to Boston College Law School Sullivan Society - $5,000 __ Please charge my Houghteling Society - $2,500 American Express MasterCard Visa Dooley Society - $1,500 Card # ________________________________________ Exp. -

Intuitive Angel Card Reader Course Guidebook

Intuitive Angel Card Reader Course Guidebook Melanie Beckler www.Ask-Angels.com CONTENTS 1 Introduction 2 Invocation 3 Our Private Facebook Group 5 Questions for Your Angel Card Readings 9 Angel Card Reading Spreads 16 30 Day Challenge 18 Certification Introduction Every aspect of this Intuitive Angel Card Readings Course has been guided by the angels. By going through the course in it’s entirely, listening to each of the videos in order, and then looping back to re-listen and dive in deeper to certain sessions, psychic tools, and experiences, the angels will help you to lift into a higher vibrational state of love and light. The intention, and energy present in this course will help you to clearly connect with an- gelic guidance, heighten your intuition, and more fully align with your highest authentic truth and light. Connecting with angels is fun, healing, powerful, enlightening and rewarding on so many levels. Be willing to set aside your preconceived notions of what connecting with the angels should be like, or might be like so you can tune into the light, power and possibilities that are present in your authentic connection with the angels that is! I’m honored that you’ve decided to join me in completing this course. If at any time you need assistance accessing the course components, or with anything at all, email us at [email protected]. With love, light and gratitude, Invocation Calling upon your angels before each and every Intuitive Angel Card Reading is an essential part of your set-up process that you will learn more about in the video course.