A PDF Copy of This Issue of Slayage Is Available Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Missouri State University Dean's List Summer 2021 (Sorted by Hometown)

Missouri State University Dean's List Summer 2021 Sorted by State, County, City 00-Unknown County Claire Edelen Holly Harding Phillip Nelson Gaige Riggs Kaelynne Schuneman Brianna Shaver Sharjenna Stump Shelena Talley Julia Vaughn Abqiq Nasser Almarri Alahsa Saeed Almarri APO Caitlin Lee Bangkok Nasha Saowapak Busan Nayeon Son Da Nang Ruby Tran Dalian Yuanyuan Chai Fan Chen Jiaxin Chen Liwen Cui Shibo Dong Handi Feng Mingyuan Hu Danlin Li Zhipeng Li Jingyi Ren Haoyu Wang Heqi Xia Jiayi Xiao Ruoxi Xu Yang Yu Haosen Zhang Xiwen Zhang Lin Zhou Chengcheng Zou Qinghan Zou Eldorado do Sul Sue Ellen Leite Hanoi Duc Le Hung Nguyen Linh Nguyen Hedel Niek Bressers Jeddah Abdul Rahman Zubi Jhapa Barsha Upreti Jiamusi Tingyuan Zhang Jiaxing Yanli Si Jining Yongxing Jiang Jinju Si Seojin Park Kampala Christine Lotigo Simon Lotigo Kavre Mamata K C Liao Yang Xinyuan Zhang Munich Bastian Thormeier Nagpur Yashasvi Moon Paderno Dugnano Mara Presot Pohang Seyeong Wi Puchong Harshytha Gunalan Rangiora Matt Jones Riyadh Ghassan Alrubaian Abdullah Alyousef Shanghai Jia Wang Shenyang Shiya Hu Tashkent Abdiaziz Abdishukurov Vekilbazar etrap Guvanch Garryyev Zhengzhou Kaiyue Wang AL-Jefferson Hueytown Shanice Stover AR-Benton Bentonville Lydia Thomas AR-Faulkner Greenbrier Cassidy Hale AR-Fulton Mammoth Spring Adam Davis AR-Pulaski Maumelle Tyson Suttle AR-Saline Benton Chloe Spann Bryant Chloe Bridges AR-Washington Fayetteville Beau Stuckey Springdale Regina Pichoff AZ-Pinal Eloy Jordan Daly CA-Orange Huntington Beach Paige Dispalatro Yorba Linda Claire Marshall -

MGM-Halloween-3

S CHOLASTIC ELT READERS A FREE RESOURCE FOR TEACHERS! HALLOWEEN–EXTRA Level 1 This level is suitable for students who have been learning English for at least a year and up to two years. It corresponds with the Common European Framework level A1. Suitable for users of CLICK magazine. SYNOPSIS Sunnydale is a small town in California. The action centres It’s Halloween. Buffy and friends hire costumes and take around the High School. Buffy and her friends are students and children out trick-or-treating (see Fact File 2). Everyone’s having Rupert Giles, Buffy’s Watcher or guide, is the librarian. Buffy, the fun. But there’s someone new in Sunnydale who wants to spoil Chosen One, has been sent to Sunnydale because the entrance their fun. His name is Ethan, he’s opened a Costume Shop and to Hell – the Hellmouth – is in the basement of the school. he has evil plans. Ethan casts a spell (he’s actually a sorcerer). The show combines comedy, tragedy, martial arts, romance Whatever costume people hired from him, that’s what they turn and horror. The stories also deal with teenage issues of love, into. Vampire-slaying Buffy loses her powers and becomes a self-esteem and planning a future, and use the fights with cowardly noblewoman from 1775. Willow becomes a ghost and supernatural forces as metaphors for emotional anxieties. Xander turns into a real-life soldier. The vampires are delighted. Halloween is Episode 6 from Series 2, so it’s quite near the Buffy and friends find themselves imprisoned in an old beginning. -

A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works Krista Silva University of Puget Sound, [email protected]

Student Research and Creative Works Book Collecting Contest Essays University of Puget Sound Year 2015 The Wonderful World of Whedon: A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works Krista Silva University of Puget Sound, [email protected] This paper is posted at Sound Ideas. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/book collecting essays/6 Krista Silva The Wonderful World of Whedon: A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works I am an inhabitant of the Whedonverse. When I say this, I don’t just mean that I am a fan of Joss Whedon. I am sincere. I live and breathe his works, the ever-expanding universe— sometimes funny, sometimes scary, and often heartbreaking—that he has created. A multi- talented writer, director and creator, Joss is responsible for television series such as Buffy the Vampire Slayer , Firefly , Angel , and Dollhouse . In 2012 he collaborated with Drew Goddard, writer for Buffy and Angel , to bring us the satirical horror film The Cabin in the Woods . Most recently he has been integrated into the Marvel cinematic universe as the director of The Avengers franchise, as well as earning a creative credit for Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. My love for Joss Whedon began in 1998. I was only eleven years old, and through an incredible moment of happenstance, and a bit of boredom, I turned the television channel to the WB and encountered my first episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer . I was instantly smitten with Buffy Summers. She defied the rules and regulations of my conservative southern upbringing. -

Animated Stereotypes –

Animated Stereotypes – An Analysis of Disney’s Contemporary Portrayals of Race and Ethnicity Alexander Lindgren, 36761 Pro gradu-avhandling i engelska språket och litteraturen Handledare: Jason Finch Fakulteten för humaniora, psykologi och teologi Åbo Akademi 2020 ÅBO AKADEMI – FACULTY OF ARTS, PSYCHOLOGY AND THEOLOGY Abstract for Master’s Thesis Subject: English Language and Literature Author: Alexander Lindgren Title: Animated Stereotypes – An Analysis of Disney’s Contemporary Portrayals of Race and Ethnicity Supervisor: Jason Finch Abstract: Walt Disney Animation Studios is currently one of the world’s largest producers of animated content aimed at children. However, while Disney often has been associated with themes such as childhood, magic, and innocence, many of the company’s animated films have simultaneously been criticized for their offensive and quite problematic take on race and ethnicity, as well their heavy reliance on cultural stereotypes. This study aims to evaluate Disney’s portrayals of racial and ethnic minorities, as well as determine whether or not the nature of the company’s portrayals have become more culturally sensitive with time. To accomplish this, seven animated feature films produced by Disney were analyzed. These analyses are of a qualitative nature, with a focus on imagology and postcolonial literary theory, and the results have simultaneously been compared to corresponding criticism and analyses by other authors and scholars. Based on the overall results of the analyses, it does seem as if Disney is becoming more progressive and culturally sensitive with time. However, while most of the recent films are free from the clearly racist elements found in the company’s earlier productions, it is quite evident that Disney still tends to rely heavily on certain cultural stereotypes. -

Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic

Please do not remove this page Giving Evil a Name: Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic Croft, Janet Brennan https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643454990004646?l#13643522530004646 Croft, J. B. (2015). Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic. Slayage: The Journal of the Joss Whedon Studies Association, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.7282/T3FF3V1J This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/10/02 09:39:58 -0400 Janet Brennan Croft1 Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic “It’s about power. Who’s got it. Who knows how to use it.” (“Lessons” 7.1) “I would suggest, then, that the monsters are not an inexplicable blunder of taste; they are essential, fundamentally allied to the underlying ideas of the poem …” (J.R.R. Tolkien, “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics”) Introduction: Names and Blood in the Buffyverse [1] In Joss Whedon’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003) and Angel (1999- 2004), words are not something to be taken lightly. A word read out of place can set a book on fire (“Superstar” 4.17) or send a person to a hell dimension (“Belonging” A2.19); a poorly performed spell can turn mortal enemies into soppy lovebirds (“Something Blue” 4.9); a word in a prophecy might mean “to live” or “to die” or both (“To Shanshu in L.A.” A1.22). -

Tv Pg 6 3-2.Indd

6 The Goodland Star-News / Tuesday, March 2, 2009 All Mountain Time, for Kansas Central TIme Stations subtract an hour TV Channel Guide Tuesday Evening March 2, 2010 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 28 ESPN 57 Cartoon Net 21 TV Land 41 Hallmark ABC Lost Lost 20/20 Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live S&T Eagle CBS NCIS NCIS: Los Angeles The Good Wife Local Late Show Letterman Late 29 ESPN 2 58 ABC Fam 22 ESPN 45 NFL NBC The Biggest Loser Parenthood Local Tonight Show w/Leno Late 2 PBS KOOD 2 PBS KOOD 23 ESPN 2 47 Food FOX American Idol Local 30 ESPN Clas 59 TV Land Cable Channels 3 KWGN WB 31 Golf 60 Hallmark 3 NBC-KUSA 24 ESPN Nws 49 E! A&E Criminal Minds CSI: Miami CSI: Miami Criminal Minds Local 5 KSCW WB 4 ABC-KLBY AMC To-Mockingbird To-Mockingbird Local 32 Speed 61 TCM 25 TBS 51 Travel ANIM 6 Weather Wild Recon Madman of the Sea Wild Recon Untamed and Uncut Madman Local 6 ABC-KLBY 33 Versus 62 AMC 26 Animal 54 MTV BET National Security Vick Tiny-Toya The Mo'Nique Show Wendy Williams Show Security Local 7 CBS-KBSL BRAVO Mill. Matchmaker Mill. Matchmaker Mill. Matchmaker Mill. Matchmaker Matchmaker 7 KSAS FOX 34 Sportsman 63 Lifetime 27 VH1 55 Discovery CMT Local Local Smarter Smarter Extreme-Home O Brother, Where Art 8 NBC-KSNK 8 NBC-KSNK 28 TNT 56 Fox Nws CNN 35 NFL 64 Oxygen Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live Anderson Local 9 Eagle COMEDY S. -

Pegasus Press Fall & Winter 2020

FALL & WINTER 2020 MSU CVM ANESTHESIA AND SMALL ANIMAL SURGERY SERVICES DELIVER STATE-OF-THE ART, SPECIALTY CARE FOR COMPANION ANIMALS THROUGHOUT THE REGION EARNING RESPECT BY EXCEEDING EXPECTATIONS and (5) continue building a robust research program to beneft the veterinary profession, our state, our nation, and our students. After working to balance goals from the strategic plan with resources and our plans to implement a visionary curriculum, we sought and received approval from COE to increase the DVM class size this June from 95 to 112, which can be accommodated Pegasus Press is published twice a year by the Mississippi State University College of Veterinary Medicine. through the two classrooms added in the 2015 building A digital version of this publication is available online at vetmed.msstate.edu/alumni-friends. project. In addition, in the Wise Center proper, the frst-year multidisciplinary laboratory (MDL) has been remodeled, and the second-year MDL is being remodeled to expand space. DR. KENT H. HOBLET DR. CARLA HUSTON Our curriculum plan includes keeping all present core clinical DEAN DIRECTOR rotations and continuing to provide clinical instruction for all ENHANCED CLINICAL EDUCATION common domestic species for all students. We will also maintain DR. RON MCLAUGHLIN approximately one-half of the fourth year for externships, ASSOCIATE DEAN DR. ALLISON GARDNER although we are moving to more four-week (as opposed to ADMINISTRATION DIRECTOR six-week) rotations. Plans are to add a combined food animal/ VETERINARY MEDICAL TECHNOLOGY PROGRAM equine emergency/after-hours rotation in the hospital and DR. DAVID SMITH a core specialty block to include cardiology, ophthalmology, INTERIM ASSOCIATE DEAN JIMMY KIGHT and dermatology. -

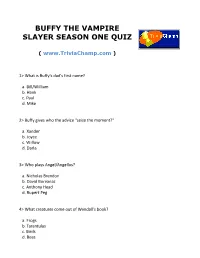

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Season One Quiz

BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER SEASON ONE QUIZ ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> What is Buffy's dad's first name? a. Bill/William b. Hank c. Paul d. Mike 2> Buffy gives who the advice "seize the moment?" a. Xander b. Joyce c. Willow d. Darla 3> Who plays Angel/Angellus? a. Nicholas Brendon b. David Boreanaz c. Anthony Head d. Rupert Peg 4> What creatures come out of Wendall's book? a. Frogs b. Tarantulas c. Birds d. Bees 5> Under Moloch's direction, what does Dave try to do to Buffy? a. Electrocute her b. Kiss her c. Stab her d. Hang her 6> Who steps in to take Marcie away? a. Angel b. Vampires c. Sunnydale Police Department d. The FBI 7> According to Giles, the earth began as what type of place? a. A home for demons b. A land for mortals c. A wasteland d. A paradise 8> What was Buffy's biology teacher's name? a. Mr. Smith b. Dr. Gregory c. Dr. Paulson d. Mr. Herring 9> What is the name of Buffy's first watcher? a. Signer b. Wilford c. Merrick d. Giles 10> Who gives Buffy a cross necklace? a. Spike b. Giles c. Cordelia d. Angel 11> What was principal Flutie's first name? a. Bob b. Ralph c. Steve d. Roy 12> What of Buffy's does Cordelia say is "over?" a. Her hairstyle b. Her shoes c. Her earrings d. Her nail polish 13> What was the name of the invisible girl? a. Marcia Craig b. Meg Stevens c. -

The Community-Centered Cult Television Heroine, 1995-2007

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 2010 "Just a Girl": The Community-Centered Cult Television Heroine, 1995-2007 Tamy Burnett University of Nebraska at Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, and the Visual Studies Commons Burnett, Tamy, ""Just a Girl": The Community-Centered Cult Television Heroine, 1995-2007" (2010). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 27. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/27 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. “JUST A GIRL”: THE COMMUNITY-CENTERED CULT TELEVISION HEROINE, 1995-2007 by Tamy Burnett A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: English (Specialization: Women‟s and Gender Studies) Under the Supervision of Professor Kwakiutl L. Dreher Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2010 “JUST A GIRL”: THE COMMUNITY-CENTERED CULT TELEVISION HEROINE, 1995-2007 Tamy Burnett, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2010 Adviser: Kwakiutl L. Dreher Found in the most recent group of cult heroines on television, community- centered cult heroines share two key characteristics. The first is their youth and the related coming-of-age narratives that result. -

Touching Queerness in Disney Films Dumbo and Lilo & Stitch

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Kingsborough Community College 2018 Touching Queerness in Disney Films Dumbo and Lilo & Stitch Katia Perea CUNY Kingsborough Community College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/kb_pubs/171 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] social sciences $€ £ ¥ Article Touching Queerness in Disney Films Dumbo and Lilo & Stitch Katia Perea Department of Sociology, City University New York, 2001 Oriental Blvd., Brooklyn, NY 11235, USA; [email protected]; Tel.: +1-718-368-5679 Received: 26 September 2018; Accepted: 1 November 2018; Published: 7 November 2018 Abstract: Disney’s influence as a cultural purveyor is difficult to overstate. From cinema screen to television programming, vacation theme parks to wardrobe, toys and books, Disney’s consistent ability to entertain children as well as adults has made it a mainstay of popular culture. This research will look at two Disney films, Dumbo (1941)1 and Lilo & Stitch (2002),2 both from distinctly different eras, and analyze the similarities in artistic styling, studio financial climate, and their narrative representation of otherness as it relates to Queer identity. Keywords: Dumbo; Lilo & Stitch; Disney; queer; mean girls; boobs and boyfriends; girl cartoon; gender; pink elephants; commodification; Walter Benjamin 1. Introduction As a Cuban-American child growing up in Miami during el exilio,3 my experience as an other meant my cultural heritage was tied to an island diaspora. -

2019-2020 Reports of the Permanent Committees and Agencies and Special Committees of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in America

2019-2020 REPORTS OF THE PERMANENT COMMITTEES AND AGENCIES AND SPECIAL COMMITTEES OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF THE PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH IN AMERICA Submitted for the FORTY-EIGHTH GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF THE PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH IN AMERICA June 16-29, 2020 Birmingham, Alabama POSTPONED Until Date to be Decided Published by the Office of the Stated Clerk of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in America Lawrenceville, Georgia 2020 PREFACE Due to the COVID-19 pandemic that emerged in the United States in early 2020, the 48th General Assembly, scheduled to meet June 16-29, 2020, in Birmingham, Alabama, was postponed until a date to be decided later. Consequently, no annual volume of the Minutes of General Assembly was published in 2020. The reports in this volume were originally prepared for the 2020 Commissioner Handbook in anticipation of the 2020 48th General Assembly. With the postponement of that Assembly due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the decision was made to post the reports on the General Assembly website so our PCA people could be informed about the work of our General Assembly ministries throughout the 2019-20 year. They are now provided in this volume for informational purposes and the historical record of the denomination. Please note that the “Recommendations” at the end of these reports will not be acted upon until the 48th General Assembly meets. Each of the Permanent Committees and Agencies and other GA committees will submit a new report for the rescheduled 48th General Assembly with new Recommendations. Note also that the Committee and Agency budgets included in the Administrative Committee report have not been approved because of the postponement of General Assembly. -

Amends Script

Amends (October 31, 1998) Written by: Joss Whedon Teaser EXT. DUBLIN STREET - NIGHT (1838) A Dickensian vista of Christmas. Snow covers the street (though it is not falling now), people and carriages milling about in it. A group of five or so CAROLLERS stand by one corner, singing a traditional Christmas air. A young man (DANIEL) in a dark suit makes his way through the people, quickly and nervously. He looks about him constantly. He passes an alley and he is suddenly GRABBED and pulled inside. He lands in a heap in the corner, the figure that grabbed him standing over him. ANGEL Why, Daniel, wherever are you going? Angel is dressed similarly -- though a bit more elegantly -- to Daniel. He is smiling graciously, and in full vampface. Daniel cowers, scrambling backwards. DANIEL You -- you're not human... ANGEL Not of late, no. DANIEL What do you want? ANGEL Well, it happens that I'm hungry, Daniel, and seeing as you're somewhat in my debt... DANIEL Please... I can't... ANGEL A man playing at cards should have a natural intelligence or a great deal of money and you're sadly lacking in both. So I'll take my winnings my own way. He grabs him, hoists him up. Daniel cannot wrest Angel's grasp from his throat. He Buffy Angel Show babbles quietly: DANIEL The lord is my shepherd, I shall not want... he maketh me to lie down in green pastures... he... ANGEL Daniel. Be of good cheer. (smiling) It's Christmas! He bites. INT. MANSION - ANGEL'S BEDROOM - NIGHT Angel awakens in a start, sweating.