The Community-Centered Cult Television Heroine, 1995-2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Word Farm 2016 Program

Word Farm 2016 Students Aubrie Amstutz Phalguni Laishram Joe Arciniega Gustavo Melo December Brown Claudia Niles Charlotte Burns Mia Roncati Derek Buss Melvin Singh Isabelle Carasso Corine Toren Christopher Connor Mel Weisberger Brendan Dassey Sydney Wiklund Phoebe DeLeon Dwight Yao Phi Do Julia Dumas Sylvia Garcia Gustavo A. Gonzalez Christine Hwynh Jae Hwan Kim Class Schedule Friday, January 29 9:00 Coffee & Snacks Sign-In 10:00-12:00 Session 1 Bryce & Jackie Zabel Tom Lazarus 12:00-1:00 Lunch 1:00-3:00 Session 2 David Gerrold Mitchell Kreigman Saturday, January 24 9:00 Coffee & Snacks 10:00-12:00 Session 3 Cheri Steinkellner J Kahn 12:00-1:00 Lunch 1:00-3:00 Session 4 Matt Allen & Lisa Mathis Dean Pitchford 3:00-3:30 Snacks 3:30-5:30 Session 5 Anne Cofell Saunders Toni Graphia 6:30 Dinner Annenberg Conference Room - 4315 SSMS Sunday, January 25 9:00 Coffee & Snacks 10:00-12:00 Session 6 Glenn Leopold Kevin McKiernan 12:00-1:00 Lunch 1:00-3:00 Session 7 Amy Pocha Allison Anders 3:00-3:30 Snacks 3:30-5:00 Session 8 Omar Najam & Mia Resella Word Farm Bios Allison Anders Allison Anders is an award-winning film and television writer and director. She attended UCLA film school and in 1984 had her first professional break working for her film mentor Wim Wenders on his movie Paris, Texas (1984). After graduation, Anders had her first film debut,Border Radio (1987), which she co-wrote and co-directed with Kurt Voss. -

Housing Court Moving to Salem

SATURDAY, DECEMBER 9, 2017 Marblehead superintendent Housing vows to address hate crimes court By Bridget Turcotte tance of paying attention to racial in- Superintendent Maryann Perry said ITEM STAFF justices within the walls of the building. in a statement Friday afternoon that in moving “We did this for people to understand light of Thursday’s events, “we continue MARBLEHEAD — A day after more that the administration needs to do to move forward as an agent of change than 100 students protested what they considered a lack of response from the more about this and the kids should in our community. be more educated that that word is not “As a result of ongoing conversations to Salem school’s administration to racially-mo- tivated incidents, the superintendent supposed to be used,” said Lany Marte, that have been occurring, including dis- vowed to give them a voice. a 15-year-old student who helped orga- cussions with students and staff that By Thomas Grillo When the clock struck noon on Thurs- nize the protest. “We’re going to be with took place today, we will be working ITEM STAFF day, schoolmates stood in solidarity out- each other for four years and by saying closely with Team-Harmony and other side Marblehead High School, holding that word and spreading hate around LYNN — Despite opposition from ten- signs and speaking about the impor- the school, it’s not good.” MARBLEHEAD, A7 ants and landlords, the Lynn Housing Court will move to Salem next month. The decision, by Chief Justice Timothy F. Sullivan, comes on the heels of a public hearing on the court’s closing this week where dozens of housing advocates told the judge to consider alternatives. -

Sloane Drayson Knigge Comic Inventory (Without

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Number Donor Box # 1,000,000 DC One Million 80-Page Giant DC NA NA 1999 NA Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 A Moment of Silence Marvel Bill Jemas Mark Bagley 2002 1 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alex Ross Millennium Edition Wizard Various Various 1999 NA Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Open Space Marvel Comics Lawrence Watt-Evans Alex Ross 1999 0 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alf Marvel Comics Michael Gallagher Dave Manak 1990 33 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 1 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 2 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 3 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 4 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 2000 5 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 2000 6 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Aphrodite IX Top Cow Productions David Wohl and Dave Finch Dave Finch 2000 0 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Veronica Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 600 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Veronica Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 601 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Veronica Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 602 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Betty Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 603 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Betty Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 -

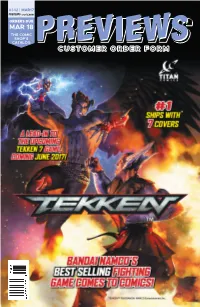

MAR17 World.Com PREVIEWS

#342 | MAR17 PREVIEWS world.com ORDERS DUE MAR 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Mar17 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 2/9/2017 1:36:31 PM Mar17 C2 DH - Buffy.indd 1 2/8/2017 4:27:55 PM REGRESSION #1 PREDATOR: IMAGE COMICS HUNTERS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS BUG! THE ADVENTURES OF FORAGER #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT/ YOUNG ANIMAL JOE GOLEM: YOUNGBLOOD #1 OCCULT DETECTIVE— IMAGE COMICS THE OUTER DARK #1 DARK HORSE IDW’S FUNKO UNIVERSE MONTH EVENT IDW ENTERTAINMENT ALL-NEW GUARDIANS TITANS #11 OF THE GALAXY #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT MARVEL COMICS Mar17 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 2/9/2017 9:13:17 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Hero Cats: Midnight Over Steller City Volume 2 #1 G ACTION LAB ENTERTAINMENT Stargate Universe: Back To Destiny #1 G AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Casper the Friendly Ghost #1 G AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Providence Act 2 Limited HC G AVATAR PRESS INC Victor LaValle’s Destroyer #1 G BOOM! STUDIOS Misfi t City #1 G BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Swordquest #0 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT James Bond: Service Special G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Spill Zone Volume 1 HC G :01 FIRST SECOND Catalyst Prime: Noble #1 G LION FORGE The Damned #1 G ONI PRESS INC. 1 Keyser Soze: Scorched Earth #1 G RED 5 COMICS Tekken #1 G TITAN COMICS Little Nightmares #1 G TITAN COMICS Disney Descendants Manga Volume 1 GN G TOKYOPOP Dragon Ball Super Volume 1 GN G VIZ MEDIA LLC BOOKS Line of Beauty: The Art of Wendy Pini HC G ART BOOKS Planet of the Apes: The Original Topps Trading Cards HC G COLLECTING AND COLLECTIBLES -

Alyson Hannigan Listing by Ren Smith Featured in USA Today

Alyson Hannigan listing by Ren Smith featured in USA Today February 14, 2018 Alyson Hannigan has a genius way of keeping organized at home Alyson Hannigan is giving us serious inspiration. Having trouble keeping your family’s schedule organized? Steal this fun DIY idea from actress Alyson Hannigan. The “How I Met Your Mother” star recently put her Santa Monica, California house up for sale, and we noticed a large chalkboard calendar on one of the walls in the kitchen area. It made us immediately want to grab a bucket of chalkboard paintand some wood to create one like it in our own homes. The wall features five rows of seven squares separated by narrow strips of wood. Along the top of the larger frame that surrounds the calendar are the names of the days of the week. Each box can be numbered with chalk according to the current month. It’s the perfect place to write down appointment reminders, your kids’ sports practice schedules and even menu plans for the week. And when you want to keep track of miscellaneous things — such as future vacation countdowns, phone numbers, or notes to family members — there’s a larger square on the side for that. The wall can easily be re-created with a few supplies from a home improvement store, and there are also so many variations you can do, such as using whiteboard paint as the base or creating the frame and boxes with Washi tape if you don’t want to work with wood. Hannigan, who has two young daughters, told People in 2016 that she loves to craft so much, she turned her guest house into a crafting room. -

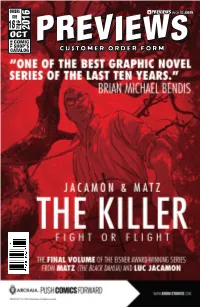

Customer Order Form

ORDERS PREVIEWS world.com DUE th 18 OCT 2016 OCT COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Oct16 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 9/8/2016 4:16:17 PM Oct16 Archie.indd 1 9/8/2016 9:50:56 AM THE LEGEND MOTOR CRUSH #1 OF ZELDA: IMAGE COMICS ART & ARTIFACTS HC DARK HORSE COMICS SUPERGIRL: BEING SUPER #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT ALIEN VS. PREDATOR: ROCKSTARS #1 LIFE AND DEATH #1 IMAGE COMICS DARK HORSE COMICS LOCKE & KEY: SMALL WORLD ONE-SHOT IDW ENTERTAINMENT JUSTICE LEAGUE VS. U.S.AVENGERS #1 SUICIDE SQUAD #1 MARVEL COMICS DC ENTERTAINMENT Oct16 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 9/8/2016 4:10:22 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Rough Riders Volume 1 TP l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Reggie & Me #1 l ARCHIE COMICS Uber: Invasion #1 l AVATAR PRESS The Avengers: Steed & Mrs Peel: The Diana Magazine Stories Volume 1 GN l BIG FINISH PRODUCTIONS Jim Henson’s The Storyteller: Giants #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Klaus and the Witch of Winter One-Shot l BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Wonder Woman ‘77 Meets the Bionic Woman 77 #1 l D.E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Red Sonja #0 l D.E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Another Castle: Grimoire TP l ONI PRESS Disney’s Great Parodies Volume 1: Mickey’s Inferno GN/HC l PAPERCUTZ Hookjaw #1 l TITAN COMICS World War X #1 l TITAN COMICS Divinity III: Stalinverse #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Tomie Complete Deluxe Editon HC l VIZ MEDIA The Pokemon Cookbook Sc l VIZ MEDIA BOOKS 2 Mercenary: The Freelance Illustration of Dan Brereton HC l ART BOOKS Krazy: The Black & White World of George Herriman HC l COMICS The Art of Archer HC l MOVIE/TV The Art of Rogue One: A Star Wars Story HC l STAR WARS Star Wars Little Golden Book: I Am a Stormtrooper l STAR WARS - YOUNG READERS MAGAZINES 2 Doctor Who Magazine Special #45: 2017 Yearbook l DOCTOR WHO Birth.Movies.Death. -

Byron Michael Purcell and Rodney S. Diggs Intend to Continue the Legacy of the Firm in Representing the Community and Bringing Justice

Allen Crabbe Hosts Free Bas- ketball Camp at Price High School Brianna Davison Gives Back to (See page B-1) Kids with Cancer (See page D-1) VOL. LXXVV, NO. 49 • $1.00 + CA. Sales Tax THURSDAY, DECEMBER 12 - 18, 2013 VOL. LXXXV NO. 33, $1.00 +CA. Sales Tax“For Over “For Eighty Over Eighty Years Years, The Voice The Voiceof Our of CommunityOur Community Speaking Speaking for forItself Itself.” THURSDAY, AUGUST 15, 2019 Byron Michael Purcell and Rodney S. Diggs intend to continue the legacy of the firm in representing the community and bringing justice. BY BRIAN W. CARTER Contributing Writer Welcome Ivie, Mc- Neill, Wyatt, Purcell & Diggs—the prestigious and Black-owned law firm in Los Angeles has added two exemplary lawyers to its title. IMW partners, Byron Michael Purcell and Rodney S. Diggs both come with a wealth of le- gal experience between the two of them and prov- en records at the firm. Se- nior partners, Rickey Ivie and Keith Wyatt shared a statement about adding their names to the firm. “Byron and Rodney have been major contribu- (From left) IMW attorneys Byron Michael Purcell and tors to the success and Rodney S Diggs. COURTESY growth of our firm for a (From left) Motown legends Smokey Robinson and Berry Gordy PHOTO E. MESIYAH MCGINNIS / SENTINEL long time. The change of dous attorneys, and we are is committed to service, the firm name is in recog- proud and blessed to work I love the commitment to BY IMANI SUMBI Harmony Gold Theater in ford, and of course, mem- nition of their past, pres- with them.”- Rickey Ivie & service—not only to its cli- Contributing Writer Los Angeles. -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. BA Bryan Adams=Canadian rock singer- Brenda Asnicar=actress, singer, model=423,028=7 songwriter=153,646=15 Bea Arthur=actress, singer, comedian=21,158=184 Ben Adams=English singer, songwriter and record Brett Anderson=English, Singer=12,648=252 producer=16,628=165 Beverly Aadland=Actress=26,900=156 Burgess Abernethy=Australian, Actor=14,765=183 Beverly Adams=Actress, author=10,564=288 Ben Affleck=American Actor=166,331=13 Brooke Adams=Actress=48,747=96 Bill Anderson=Scottish sportsman=23,681=118 Birce Akalay=Turkish, Actress=11,088=273 Brian Austin+Green=Actor=92,942=27 Bea Alonzo=Filipino, Actress=40,943=114 COMPLETEandLEFT Barbara Alyn+Woods=American actress=9,984=297 BA,Beatrice Arthur Barbara Anderson=American, Actress=12,184=256 BA,Ben Affleck Brittany Andrews=American pornographic BA,Benedict Arnold actress=19,914=190 BA,Benny Andersson Black Angelica=Romanian, Pornstar=26,304=161 BA,Bibi Andersson Bia Anthony=Brazilian=29,126=150 BA,Billie Joe Armstrong Bess Armstrong=American, Actress=10,818=284 BA,Brooks Atkinson Breanne Ashley=American, Model=10,862=282 BA,Bryan Adams Brittany Ashton+Holmes=American actress=71,996=63 BA,Bud Abbott ………. BA,Buzz Aldrin Boyce Avenue Blaqk Audio Brother Ali Bud ,Abbott ,Actor ,Half of Abbott and Costello Bob ,Abernethy ,Journalist ,Former NBC News correspondent Bella ,Abzug ,Politician ,Feminist and former Congresswoman Bruce ,Ackerman ,Scholar ,We the People Babe ,Adams ,Baseball ,Pitcher, Pittsburgh Pirates Brock ,Adams ,Politician ,US Senator from Washington, 1987-93 Brooke ,Adams -

4.5.1 Los Abducidos: El Duro Retorno En Expediente X Se Duda De Si Las

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Diposit Digital de Documents de la UAB 4.5.1 Los abducidos: El duro retorno En Expediente X se duda de si las abducciones son obra de humanos o de extraterrestres por lo menos hasta el momento en que Mulder es abducido al final de la Temporada 7. La duda hace que el encuentro con otras personas que dicen haber sido abducidas siempre tenga relevancia para Mulder, Scully o ambos, como se puede ver con claridad en el caso de Cassandra Spender. Hasta que él mismo es abducido se da la paradójica situación de que quien cree en la posibilidad de la abducción es él mientras que Scully, abducida en la Temporada 2, siempre duda de quién la secuestró, convenciéndose de que los extraterrestres son responsables sólo cuando su compañero desaparece (y no necesariamente en referencia a su propio rapto). En cualquier caso poco importa en el fondo si el abducido ha sido víctima de sus congéneres humanos o de alienígenas porque en todos los casos él o ella cree –con la singular excepción de Scully– que sus raptores no son de este mundo. Como Leslie Jones nos recuerda, las historias de abducción de la vida real que han inspirado este aspecto de Expediente X “expresan una nueva creencia, tal vez un nuevo temor: a través de la experimentación sin emociones realizada por los alienígenas usando cuerpos humanos adquiridos por la fuerza, se demuestra que el hombre pertenece a la naturaleza, mientras que los extraterrestres habitan una especie de supercultura.” (Jones 94). -

Amends Script

Amends (October 31, 1998) Written by: Joss Whedon Teaser EXT. DUBLIN STREET - NIGHT (1838) A Dickensian vista of Christmas. Snow covers the street (though it is not falling now), people and carriages milling about in it. A group of five or so CAROLLERS stand by one corner, singing a traditional Christmas air. A young man (DANIEL) in a dark suit makes his way through the people, quickly and nervously. He looks about him constantly. He passes an alley and he is suddenly GRABBED and pulled inside. He lands in a heap in the corner, the figure that grabbed him standing over him. ANGEL Why, Daniel, wherever are you going? Angel is dressed similarly -- though a bit more elegantly -- to Daniel. He is smiling graciously, and in full vampface. Daniel cowers, scrambling backwards. DANIEL You -- you're not human... ANGEL Not of late, no. DANIEL What do you want? ANGEL Well, it happens that I'm hungry, Daniel, and seeing as you're somewhat in my debt... DANIEL Please... I can't... ANGEL A man playing at cards should have a natural intelligence or a great deal of money and you're sadly lacking in both. So I'll take my winnings my own way. He grabs him, hoists him up. Daniel cannot wrest Angel's grasp from his throat. He Buffy Angel Show babbles quietly: DANIEL The lord is my shepherd, I shall not want... he maketh me to lie down in green pastures... he... ANGEL Daniel. Be of good cheer. (smiling) It's Christmas! He bites. INT. MANSION - ANGEL'S BEDROOM - NIGHT Angel awakens in a start, sweating. -

Odwołany Za Śmieci

Nr 11 Wprost pod 15 MARCA 2001 r. lokomotywę ISSN 1232-0366 7 X INDEKS: 328073 Cena: 2 ,0 0 zł owircl (w tym 7% VAT) NAJSTARSZE PISMO W REGIONIE. UKAZUJE SIĘ OD 1947 ROKU. Głuchołazy Zdenerwował się, bo obchodziła Dzień Kobiet Nieuwaga kierowcy fiata ducato sprawiła, że minio Luksusowy iż widział nadjeżdżający pociąg, wjechał nagle wprost pod koła lokomotywy. pustostan • czytaj n a str. 2 Mieszkanie o powierzchni po ZABIŁ nad 130 m kw. w centrum miasta od dwóch lat stoi puste i czeka na loka Mycie na granicy torów - rodzinę Szafrańskich z Jar nołtówka. • słr. 13 O tm uchów KONKUBINĘ W swoje gniazdo srasz? Nielegalna wycinka 10 drzew doprowadziła do konfliktu wśród mieszkańców Ligoty Wielkiej. Wieś podzieliła się na dwa obozy. Z Czech do Polski przechodzimy i • str. 11 przejeżdżamy przez roztwór sody Niem odlin kaustycznej • czytaj tia str. 5 Pomoc z Peine W N iem odlinie przebywała 11- osobowa grupa członków elitarne Odwołany go „Rotary Club” z zaprzyjaźnione go niemieckiego miasta Peine. • str. 14 za śmieci Paczków W ubiegły czwartek Zarząd Miejski w Nysie odwo łał Stanisława Ostrowskiego z funkcji prezesa należą cej do gminy spółki EKOM. Stan dobry, ale... Zdaniem Zarządu, w ostatnich miesiącach EKOM Targowisko w Paczkowie to jed W niedzielę sąd podjął decyzję o aresztowaniu sprawcy prowadził działania zmierzające do zawyżenia kosztów na wielka prowizorka, a oddalone o eksploatacji wysypiska w Domaszkowicach, a co się z niecałe 3 kilometry od miasta przej W czwartek 8 marca na ostatnim piętrze w jednym z nyskich bloków w Rynku 35-letni tym wiąże do nieuzasadnionego podniesienia cen wy ście graniczne nie spełnia norm sa pijany mężczyzna zakatował swoją konkubinę. -

Undead, Gothic, and Queer: the Allure of Buffy

Book Reviews UNDEAD, GOTHIC, AND QUEER: THE ALLURE OF BUFFY by Pamela O’Donnell Elena Levine & Lisa Parks, eds., UNDEAD TV: ESSAYS ON BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007. 209p. bibl. index. notes. ISBN 978-0-8223-4043-0. Rebecca Beirne, ed., TELEVISING QUEER WOMEN: A READER, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008. 25p. bibl. index. notes. ISBN 0-230-60080-8. Benjamin A. Brabon & Stéphanie Genz, eds., POSTFEMINIST GOTHIC: CRITICAL INTERVENTIONS IN CONTEMPORARY CULTURE, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007. 89p. index. notes. ISBN 0-230-00542-X. Buffy the Vampire Slayer( BtVS) died twice in the course of the series. canceled, expired material for maxi- may well be the most analyzed televi- Perhaps more than any other televi- mum return” (p.5). Can anyone say sion show in the history of the me- sion show, BtVS deserves to be called Knight Rider? dium. Try to name another series that “undead TV,” the title chosen by Elana Because the introduction raises so has its own academic conference or its Levine and Lisa Parks for their anthol- many interesting points about BtVS’s own peer-reviewed journal. A quick ogy of eight essays exploring the cul- afterlife — including how the show’s search of Amazon.com turns up more tural impact of BtVS (p.3). move from the WB to UPN may have than a dozen scholarly volumes about doomed the two “netlets” — it’s frus- the show — from the ground-breaking In the acknowledgements section trating to discover that very few of the Why Buffy Matters to the soon-to-be- of Undead TV: Essays on Buffy the Vam- essays use this as a point of departure published Buffy Goes Dark: Essays on pire Slayer, Levine and Parks note that for their analysis.2 Indeed, more than the Final Two Seasons.