Filmic Tomboy Narrative and Queer Feminist Spectatorship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Undergraduate Dissertation Trabajo Fin De Grado

Undergraduate Dissertation Trabajo Fin de Grado “Hell is a Teenage Girl”: Female Monstrosity in Jennifer's Body Author Victoria Santamaría Ibor Supervisor Maria del Mar Azcona Montoliú FACULTY OF ARTS 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………….1 2. FEMALE MONSTERS………………………………………………………….3 3. JENNIFER’S BODY……………………………………………………………..8 3.1. A WOMAN’S SACRIFICE…………………………………………………8 3.2. “SHE IS ACTUALLY EVIL, NOT HIGH SCHOOL EVIL”: NEOLIBERAL MONSTROUS FEMININITY……………………………………………..13 3.3. MEAN MONSTERS: FEMALE COMPETITION AS SOURCE OF MONSTROSITY…………………………………………………………..18 4. CONCLUSION………………………………………………………………...24 5. WORKS CITED………………………………………………………………..26 6. FILMS CITED………………………………………………………………….29 1. INTRODUCTION Jennifer’s Body, released in 2009, is a teen horror film directed by Karyn Kusama and written by Diablo Cody. It stars Megan Fox and Amanda Seyfried, playing Jennifer, the archetypal popular girl, and Anita “Needy,” her co-dependent best friend, respectively. Jennifer is a manipulative and overly sexual teenager who, as the result of a satanic ritual, is possessed by a demon and starts devouring her male classmates. Knowing that her friend is a menace, Needy decides she has to stop her. The marketing strategy behind Jennifer’s Body capitalized on Megan Fox’s emerging status as a sex symbol after her role in Transformers (dir. Michael Bay, 2007), as can be seen in the promotional poster (see fig. 1) and in the official trailer, in which Jennifer is described as the girl “every guy would die for.” The movie, which was a flop at the time of its release (grossing only $31.6 million worldwide for a film made on a $16 million Figure 1: Promotional poster budget) was criticised by some reviewers for not giving its (male) audience what it promised. -

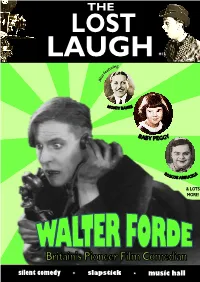

The Lost Laugh

#12 1 April 2020 Welcome to issue 12 of THE LOST LAUGH. I hope, wherever this reaches you, that you’re coping OK with these troubled times, and keeping safe and well. These old, funny films are a great form of escapism and light relief at times like these. In fact, I was thinking the other day that the times they were made in had their fair share of troubles : two world wars, the 1918 flu pandemic, the Wall Street Crash and the great depression, to name a few. Yet, these comics made people smile, often even making fun out of the anxi- eties of the day. That they can still make us smile through our own troubles, worlds away from their own, is testament to how special they are. I hope reading this issue helps you forget the outside world for a while and perhaps gives you some new ideas for films to seek out to pass some time in lockdown. Thanks to our contributors this issue: David Glass, David Wyatt and Ben Model; if you haven't seen them yet, Ben’s online silent comedy events are a terrific idea that help to keep the essence of live silent cinema alive. Ben has very kindly taken time to answer some questions about the shows. As always, please do get in touch at [email protected] with any comments or suggestions, or if you’d like to contribute an article (or plug a project of your own!) in a future issue. Finally, don’t for- get that there are more articles, including films to watch online, at thelostlaugh.com. -

DVD Movie List by Genre – Dec 2020

Action # Movie Name Year Director Stars Category mins 560 2012 2009 Roland Emmerich John Cusack, Thandie Newton, Chiwetel Ejiofor Action 158 min 356 10'000 BC 2008 Roland Emmerich Steven Strait, Camilla Bella, Cliff Curtis Action 109 min 408 12 Rounds 2009 Renny Harlin John Cena, Ashley Scott, Aidan Gillen Action 108 min 766 13 hours 2016 Michael Bay John Krasinski, Pablo Schreiber, James Badge Dale Action 144 min 231 A Knight's Tale 2001 Brian Helgeland Heath Ledger, Mark Addy, Rufus Sewell Action 132 min 272 Agent Cody Banks 2003 Harald Zwart Frankie Muniz, Hilary Duff, Andrew Francis Action 102 min 761 American Gangster 2007 Ridley Scott Denzel Washington, Russell Crowe, Chiwetel Ejiofor Action 113 min 817 American Sniper 2014 Clint Eastwood Bradley Cooper, Sienna Miller, Kyle Gallner Action 133 min 409 Armageddon 1998 Michael Bay Bruce Willis, Billy Bob Thornton, Ben Affleck Action 151 min 517 Avengers - Infinity War 2018 Anthony & Joe RussoRobert Downey Jr., Chris Hemsworth, Mark Ruffalo Action 149 min 865 Avengers- Endgame 2019 Tony & Joe Russo Robert Downey Jr, Chris Evans, Mark Ruffalo Action 181 mins 592 Bait 2000 Antoine Fuqua Jamie Foxx, David Morse, Robert Pastorelli Action 119 min 478 Battle of Britain 1969 Guy Hamilton Michael Caine, Trevor Howard, Harry Andrews Action 132 min 551 Beowulf 2007 Robert Zemeckis Ray Winstone, Crispin Glover, Angelina Jolie Action 115 min 747 Best of the Best 1989 Robert Radler Eric Roberts, James Earl Jones, Sally Kirkland Action 97 min 518 Black Panther 2018 Ryan Coogler Chadwick Boseman, Michael B. Jordan, Lupita Nyong'o Action 134 min 526 Blade 1998 Stephen Norrington Wesley Snipes, Stephen Dorff, Kris Kristofferson Action 120 min 531 Blade 2 2002 Guillermo del Toro Wesley Snipes, Kris Kristofferson, Ron Perlman Action 117 min 527 Blade Trinity 2004 David S. -

Robert Heide Meeting Jackie

Excerpt from When Jackie Met Ethyl / Curated by Dan Cameron, May 5 – June 1, 2016 © 2016 Howl! Arts, Inc. Page 1 Robert Heide Meeting Jackie I first met Jackie Curtis through theater director Ron Link, during rehearsals of Jackie’s outrageous nostalgic/camp Hollywood comedy-play Glamour Glory, and Gold at Bastiano’s Cellar Studio in the Village. In the cast were platinum Melba LaRose Jr. playing a Jean Harlow-type screen siren, Robert De Niro in his very first acting role playing all the male parts, and Candy Darling, still a brunette before being transformed by Link—with the help of Max Factor theatrical make-up, false eyelashes, blue eye shadow, and for her hair, 20 volume peroxide mixed with white henna ammonia—into the super-blonde Goddess she is thought of today. Jackie also became a Warhol Superstar, along with her glamorous sisters Candy and Holly Woodlawn. At the time of my first introduction, Jackie was a pretty boy wearing wire-rimmed eyeglasses with natural rosy cheeks and brown hair. Initially shy and introverted, he was given a quick makeover by Svengali Link and changed, with the help of red henna, into a flaming redhead with glossy scarlet lips à la Barbara Stanwyck, Jackie’s favorite film star. Gobs of facial glitter would later add to the mix. During the run of Glamour, Glory, and Gold, Sally Kirkland, who lived upstairs from me on Christopher Street, brought along her friend Shelley Winters to Bastiano’s to see Jackie’s show. Shelley was about to open in her own play, One Night Stands of a Noisy Passenger, at the Actors’ Playhouse on Sheridan Square, and became enamored with the young, sexy, muscular De Niro, deciding to cast him in her show, where he ran around stage in his bathing trunks. -

Missions and Film Jamie S

Missions and Film Jamie S. Scott e are all familiar with the phenomenon of the “Jesus” city children like the film’s abused New York newsboy, Little Wfilm, but various kinds of movies—some adapted from Joe. In Susan Rocks the Boat (1916; dir. Paul Powell) a society girl literature or life, some original in conception—have portrayed a discovers meaning in life after founding the Joan of Arc Mission, variety of Christian missions and missionaries. If “Jesus” films while a disgraced seminarian finds redemption serving in an give us different readings of the kerygmatic paradox of divine urban mission in The Waifs (1916; dir. Scott Sidney). New York’s incarnation, pictures about missions and missionaries explore the East Side mission anchors tales of betrayal and fidelity inTo Him entirely human question: Who is or is not the model Christian? That Hath (1918; dir. Oscar Apfel), and bankrolling a mission Silent movies featured various forms of evangelism, usually rekindles a wealthy couple’s weary marriage in Playthings of Pas- Protestant. The trope of evangelism continued in big-screen and sion (1919; dir. Wallace Worsley). Luckless lovers from different later made-for-television “talkies,” social strata find a fresh start together including musicals. Biographical at the End of the Trail mission in pictures and documentaries have Virtuous Sinners (1919; dir. Emmett depicted evangelists in feature films J. Flynn), and a Salvation Army mis- and television productions, and sion worker in New York’s Bowery recent years have seen the burgeon- district reconciles with the son of the ing of Christian cinema as a distinct wealthy businessman who stole her genre. -

FILMART Flyer

NEW! NEW! NEW! NEW! From the Producer of NEW! THE WALKING DEAD IN PRODUCTION IN PRODUCTION FILMART Attending: March 23th - 25th Scott Veltri | [email protected] h RESULTS - SCREENING IN MARKET! (Drama) Directed by ANDREW BULJALSKI (Computer Chess) Starring GUY PEARCE (Memento), COBIE SMULDERS (How I met your Mother), KEVIN CORRIGAN (The Depart- ed), GIOVANNI RIBISI (Saving Private Ryan), ANTHONY MICHAEL HALL (The Dead Zone), BROOKLYN DECKER (Just Go With It) Recently divorced, newly rich, and utterly miserable, Danny (Kevin Corrigan) struggles to find a balance between money and happiness. Danny’s well-funded boredom is interrupted by a momentous trip to the local gym, where he meets self-styled guru/owner Trevor (Guy Pearce) and abrasive yet irresistable trainer Kat (Cobie Smulders). Soon their three lives become intertwined, both professionally and personally. THE WRECKING CREW - SCREENING IN MARKET! (Documentary) Directed by DANNY TEDESCO Featuring interviews with Brian Wilson, Cher, Nancy Sinatra, Glen Campbell What the Funk Brothers did for Motown…The Wrecking Crew did, only bigger, for the West Coast Sound. Six years in a row in the 1960’s and early 1970’s, the Grammy for “Record of the Year” went to Wrecking Crew recordings. The Wrecking Crew tells the story of the unsung musicians that provided the back- beat, the bottom and the swinging melody that drove many of the number one hits of the 1960’s. TANGERINE (Comedy / Drama) Directed by SEAN BAKER (Starlet) Starring KITANA KIKI RODRIGUEZ, MYA TAYLOR, KARREN KARAGULIAN, MICKEY O’HAGAN, ALLA TUMANIAN, JAMES RANSONE It’s Christmas Eve in Tinseltown and Sin-Dee is back on the block. -

Jodie Foster Une Certaine Idée De La Femme Sylvie Gendron

Document generated on 09/30/2021 10:09 p.m. Séquences La revue de cinéma Jodie Foster Une certaine idée de la femme Sylvie Gendron L’ONF : U.$. qu’on s’en va? Number 176, January–February 1995 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/49736ac See table of contents Publisher(s) La revue Séquences Inc. ISSN 0037-2412 (print) 1923-5100 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Gendron, S. (1995). Jodie Foster : une certaine idée de la femme. Séquences, (176), 30–33. Tous droits réservés © La revue Séquences Inc., 1994 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Gros plan Jodie Une certaine idée Dire de Jodie Foster qu'elle est une actrice remarquable à tous points de vue est à la fois une réalité et une observation d'une banalité sans nom. Il n'y a qu'à voir ses films pour constater son talent. Ne retenons que ceux qui sont dignes d'intérêt et ils sont assez nombreux. The Silence of the Lambs 1 serait bien vain et surtout redondant de chercher fance; ce pouvait aussi être un rêve de pédophile. Je — dans le vrai sens du terme — prétendant être des à chanter sur tous les tons les louanges de la belle reste convaincue que les publicitaires de l'époque adultes. -

INTRODUCTION Fatal Attraction and Scarface

1 introduction Fatal Attraction and Scarface How We Think about Movies People respond to movies in different ways, and there are many reasons for this. We have all stood in the lobby of a theater and heard conflicting opin- ions from people who have just seen the same film. Some loved it, some were annoyed by it, some found it just OK. Perhaps we’ve thought, “Well, what do they know? Maybe they just didn’t get it.” So we go to the reviewers whose business it is to “get it.” But often they do not agree. One reviewer will love it, the next will tell us to save our money. What thrills one person may bore or even offend another. Disagreements and controversies, however, can reveal a great deal about the assumptions underlying these varying responses. If we explore these assumptions, we can ask questions about how sound they are. Questioning our assumptions and those of others is a good way to start think- ing about movies. We will soon see that there are many productive ways of thinking about movies and many approaches that we can use to analyze them. In Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story (1992), the actor playing Bruce Lee sits in an American movie theater (figure 1.1) and watches a scene from Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) in which Audrey Hepburn’s glamorous character awakens her upstairs neighbor, Mr Yunioshi. Half awake, he jumps up, bangs his head on a low-hanging, “Oriental”-style lamp, and stumbles around his apart- ment crashing into things. -

JOAN CRAWFORD Early Life and Inspiration Joan Crawford Was Born Lucille Fay Lesueur on March 23, 1908, in San Antonio, Texas

JOAN CRAWFORD Early Life and Inspiration Joan Crawford was born Lucille Fay LeSueur on March 23, 1908, in San Antonio, Texas. Her biological father, Thomas E. LeSueur, left the family shortly after Lucille’s birth, leaving Anna Bell Johnson, her mother, behind to take care of the family. page 1 Lucille’s mother later married Henry J. Cassin, an opera house owner from Lawton, Oklahoma, which is where the family settled. Throughout her childhood there, Lucille frequently watched performances in her stepfather’s theater. Lucille, having grown up watching the many vaudeville acts perform at the theater, grew up wanting to pursue a dancing career. page 2 In 1917, Lucille’s family moved to Kansas City after her stepfather was accused of embezzlement. Cassin, a Catholic, sent Lucille to a Catholic girls’ school by the name of St. Agnes Academy. When her mother and stepfather divorced, she remained at the academy as a work student. It was there that she began dating and met a man named Ray Sterling, who inspired her to start working hard in school. page 3 In 1922, Lucille registered at Stephens College in Columbia, Missouri. However, she only attended the college for a few months before dropping out when she realized that she was not prepared enough for college. page 4 Early Career After her stint at Stephens, Lucille began dancing in various traveling choruses under the name Lucille LeSueur. While performing in Detroit, her talent was noticed by a producer named Jacob Shubert. Shubert gave her a spot in his 1924 Broadway show Innocent Eyes, in which she performed in the chorus line. -

Heroes (TV Series) - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Pagina 1 Di 20

Heroes (TV series) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Pagina 1 di 20 Heroes (TV series) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Heroes was an American science fiction Heroes television drama series created by Tim Kring that appeared on NBC for four seasons from September 25, 2006 through February 8, 2010. The series tells the stories of ordinary people who discover superhuman abilities, and how these abilities take effect in the characters' lives. The The logo for the series featuring a solar eclipse series emulates the aesthetic style and storytelling Genre Serial drama of American comic books, using short, multi- Science fiction episode story arcs that build upon a larger, more encompassing arc. [1] The series is produced by Created by Tim Kring Tailwind Productions in association with Starring David Anders Universal Media Studios,[2] and was filmed Kristen Bell primarily in Los Angeles, California. [3] Santiago Cabrera Four complete seasons aired, ending on February Jack Coleman 8, 2010. The critically acclaimed first season had Tawny Cypress a run of 23 episodes and garnered an average of Dana Davis 14.3 million viewers in the United States, Noah Gray-Cabey receiving the highest rating for an NBC drama Greg Grunberg premiere in five years. [4] The second season of Robert Knepper Heroes attracted an average of 13.1 million Ali Larter viewers in the U.S., [5] and marked NBC's sole series among the top 20 ranked programs in total James Kyson Lee viewership for the 2007–2008 season. [6] Heroes Masi Oka has garnered a number of awards and Hayden Panettiere nominations, including Primetime Emmy awards, Adrian Pasdar Golden Globes, People's Choice Awards and Zachary Quinto [2] British Academy Television Awards. -

Anney Perrine

ANNEY PERRINE Costume Designer www.anneyperrine .com YOUTH IN OREGON • Sundial Pictures • 2015 • Director: Joel David Moore • Producers: Joey Carey, Stefan Nowicki Cast: Frank Langella, Billy Crudup, Christina Applegate CUSTODY • Lucky Monkey Pictures • 2015 • Director: James Lapine • Producers: Katie Mustard, Lauren Versel Cast: Viola Davis, Ellen Burstyn, Hayden Panettiere, Catalina Moreno, Tony Shaloub, Dan Fogler THE PHENOM • Elephant Eye Films • 2014 • Director: Noah Buschel • Producers: Jeff Rice, Kim Jose, Aaron L. Gilbert Cast: Ethan Hawke, Paul Giamatti, Johnny Simmons, Sophie Kennedy Clark, Marin Ireland THE OUTSKIRTS • BCDF Pictures • 2014 • Director: Peter Hutchings • Producers: Brice Del Farra, Claude Del Farra Cast: Eden Sher, Victoria Justice, Peyton List, Ashley Rickards AD INEXPLORATA • Loveless • 2014 • Director: Mark Rosenberg • Producers: Josh Penn, Matthew Parker, Jason Berman Cast: Mark Strong, Sanaa Lathan, Luke Wilson BEFORE WE GO • G4 Productions • 2013 • Director: Chris Evans • Producers: McG, Mark Kassen, Mary Viola Cast: Chris Evans, Alice Eve, Emma Fitzpatrick *Special Presentation: Toronto International Film Festival 2014 ABOUT ALEX • Bedford Falls Co. • 2013 • Dir: Jesse Zwick • Prod: Edward Zwick, Marshall Herskovitz, Robyn Bennett, Adam Saunders Cast: Aubrey Plaza, Max Minghella, Nate Parker, Jason Ritter, Maggie Grace, Max Greenfield *Official Selection: Tribeca Film Festival 2014 MAHJONG AND THE WEST • BCDF Pictures & Apres Visuals • 2013 • Dir: Joseph Muszynski • Prod: Claude Dal Farra, Adam Piotrowicz Cast: Dominic Bogart, Tom Guiry, Louanne Stephens MEDAL OF VICTORY • Warehouse District Productions • 2013 • Director: Joshua Moise • Producer: Jason Schumacher Cast: Richard Riehle, Will Blomker COLD COMES THE NIGHT • Syncopated Films • 2012 • Dir: Tze Chun • Producers: Terry Leonard, Mynette Louie, Rick Rosenthal Cast: Bryan Cranston, Alice Eve, Logan Marshall-Green, Ursula Parker, Leo Fitzpatrick A BIRDER’S GUIDE TO EVERYTHING • Dreamfly Prod. -

The Cultural Traffic of Classic Indonesian Exploitation Cinema

The Cultural Traffic of Classic Indonesian Exploitation Cinema Ekky Imanjaya Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of East Anglia School of Art, Media and American Studies December 2016 © This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. 1 Abstract Classic Indonesian exploitation films (originally produced, distributed, and exhibited in the New Order’s Indonesia from 1979 to 1995) are commonly negligible in both national and transnational cinema contexts, in the discourses of film criticism, journalism, and studies. Nonetheless, in the 2000s, there has been a global interest in re-circulating and consuming this kind of films. The films are internationally considered as “cult movies” and celebrated by global fans. This thesis will focus on the cultural traffic of the films, from late 1970s to early 2010s, from Indonesia to other countries. By analyzing the global flows of the films I will argue that despite the marginal status of the films, classic Indonesian exploitation films become the center of a taste battle among a variety of interest groups and agencies. The process will include challenging the official history of Indonesian cinema by investigating the framework of cultural traffic as well as politics of taste, and highlighting the significance of exploitation and B-films, paving the way into some findings that recommend accommodating the movies in serious discourses on cinema, nationally and globally.