A Comparative Analysis of Paratextual Elements in the Complete Translations of Gulliver’S Travels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"A Battle of Wits": Tubbian Entrapment in Swift

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2006 ”A battle of wits”: Tubbian entrapment in Swift Frischknecht, Andreas Abstract: Mein auf Leserreaktion basierender Zugang zu Swift beabsichtigt zu zeigen, dass Swifts satirische Schriften vor allem die Gefangennahme ihrer Leser zum Ziel haben. Satire wird somit als aktiver, den Leser miteinbeziehender Prozess betrachtet und ihre Eigenschaften und Strategien als ”Tön- nern” bezeichnet. Dies geschieht im Bezug auf das Bild der Tonne, welches gleichsam für Satire und daraus resultierende Lesergefangennahme in Swift steht und von Swift in seiner ersten grossen Satire, A Tale of a Tub, entwickelt wurde. Es gibt verschiedene ”Tönnerne” Eigenschaften in Swift. Swifts Satire ”neigt zur Drehung”; sie ist ”hohl” und ”leer”; sie ist ”lärmig, und hölzern”; und sie ist schliesslich besonders geeignet, ihre Leser, Walen gleich, ”durch Vergnügen” abzulenken (Tale 40). Folglich sind die markan- testen Merkmale ein Gefühl der Instabilität aufgrund konstanter perspektivischer Wechsel (”Drehen”); extremistische Natur und gleichzeitige Kritik an Extremismus, also Paradox, von einer grundsätzlichen Zirkularität der Methode stammend (die Form der Tonne); Leere, Abwesenheit des Autors durch Zuhil- fenahme satirischer personae und ein daraus folgendes Wertevakuum, in das der Leser gefangen wird und gezwungen, seine eigenen Entscheidungen zu treffen; Materialismus und Körperlichkeit, die satirische Methode der Demütigung durch körperliche Entfremdung; und schliesslich die Absicht des Erweckens von Interesse und Verwirrung durch eine Ansammlung verschiedenster Sichtweisen. My reader-response approach to Swift tries to show that Swift’s satiric writings are primarily designed to entrap their read- ers. Satire is perceived as process in action. -

Shakespeare in Geneva

Shakespeare in Geneva SHAKESPEARE IN GENEVA Early Modern English Books (1475-1700) at the Martin Bodmer Foundation Lukas Erne & Devani Singh isbn 978-2-916120-90-4 Dépôt légal, 1re édition : janvier 2018 Les Éditions d’Ithaque © 2018 the bodmer Lab/université de Genève Faculté des lettres - rue De-Candolle 5 - 1211 Genève 4 bodmerlab.unige.ch TABLE OF CONTENts Acknowledgements 7 List of Abbreviations 8 List of Illustrations 9 Preface 11 INTRODUctION 15 1. The Martin Bodmer Foundation: History and Scope of Its Collection 17 2. The Bodmer Collection of Early Modern English Books (1475-1700): A List 31 3. The History of Bodmer’s Shakespeare(s) 43 The Early Shakespeare Collection 43 The Acquisition of the Rosenbach Collection (1951-52) 46 Bodmer on Shakespeare 51 The Kraus Sales (1970-71) and Beyond 57 4. The Makeup of the Shakespeare Collection 61 The Folios 62 The First Folio (1623) 62 The Second Folio (1632) 68 The Third Folio (1663/4) 69 The Fourth Folio (1685) 71 The Quarto Playbooks 72 An Overview 72 Copies of Substantive and Partly Substantive Editions 76 Copies of Reprint Editions 95 Other Books: Shakespeare and His Contemporaries 102 The Poetry Books 102 Pseudo-Shakespeare 105 Restoration Quarto Editions of Shakespeare’s Plays 106 Restoration Adaptations of Plays by Shakespeare 110 Shakespeare’s Contemporaries 111 5. Other Early Modern English Books 117 NOTE ON THE CATALOGUE 129 THE CATALOGUE 135 APPENDIX BOOKS AND MANUscRIPts NOT INCLUDED IN THE CATALOGUE 275 Works Cited 283 Acknowledgements We have received precious help in the course of our labours, and it is a pleasure to acknowl- edge it. -

Gullivers Travels: Retold from the Jonathan Swift Original Pdf, Epub, Ebook

GULLIVERS TRAVELS: RETOLD FROM THE JONATHAN SWIFT ORIGINAL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jonathan Swift,Martin Woodside,Jamel Akib,Arthur Pober | 160 pages | 26 Oct 2006 | Sterling Juvenile | 9781402726620 | English | New York, United States Gullivers Travels: Retold from the Jonathan Swift Original PDF Book In the discipline of computer architecture , the terms big-endian and little-endian are used to describe two possible ways of laying out bytes in memory. See also: Floating cities and islands in fiction. Related topics. Learn more - opens in a new window or tab. Outline Category. And shall we condemn a preacher of righteousness for exposing under the character of a nasty, unteachable Yahoo the deformity, the blackness, the filthiness, and corruption of those hellish abominable vices, which inflame the wrath of God against the children of disobedience. They are authoritarian there is no dissent or difference of opinion. Please enter 5 or 9 numbers for the ZIP Code. The orthodox Christian identification of the diminutive sinner with small unclean animals is made implicitly throughout the episode. Main article: Cultural influence of Gulliver's Travels. I guessed his meaning and my good fortune gave me so much presence of mind that I resolved not to struggle in the least as he held me in the air above sixty foot from the ground, although he grievously pinched my sides, for fear I should slip through his fingers. These were mostly printed anonymously or occasionally pseudonymously and were quickly forgotten. Film adaptations have tended to focus on the first two stories and include an animated film produced by the Fleischer brothers , a partially animated musical version starring Richard Harris as Gulliver, and a two- part television movie starring Ted Danson. -

Pdf\Preparatory\Charles Wesley Book Catalogue Pub.Wpd

Proceedings of the Charles Wesley Society 14 (2010): 73–103. (This .pdf version reproduces pagination of printed form) Charles Wesley’s Personal Library, ca. 1765 Randy L. Maddox John Wesley made a regular practice of recording in his diary the books that he was reading, which has been a significant resource for scholars in considering influences on his thought.1 If Charles Wesley kept such diary records, they have been lost to us. However, he provides another resource among his surviving manuscript materials that helps significantly in this regard. On at least four occasions Charles compiled manuscript catalogues of books that he owned, providing a fairly complete sense of his personal library around the year 1765. Indeed, these lists give us better records for Charles Wesley’s personal library than we have for the library of brother John.2 The earliest of Charles Wesley’s catalogues is found in MS Richmond Tracts.3 While this list is undated, several of the manuscript hymns that Wesley included in the volume focus on 1746, providing a likely time that he started compiling the list. Changes in the color of ink and size of pen make clear that this was a “growing” list, with additions being made into the early 1750s. The other three catalogues are grouped together in an untitled manuscript notebook containing an assortment of financial records and other materials related to Charles Wesley and his family.4 The first of these three lists is titled “Catalogue of Books, 1 Jan 1757.”5 Like the earlier list, this date indicates when the initial entries were made; both the publication date of some books on the list and Wesley’s inscriptions in surviving volumes make clear that he continued to add to the list over the next few years. -

Politics in Jonathan Swift's Literature

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Repositorio Documental de la Universidad de Valladolid FACULTAD de FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO de FILOLOGÍA INGLESA Grado en Estudios Ingleses TRABAJO DE FIN DE GRADO Politics in Jonathan Swift’s Literature Rebeca Carravilla Izquierdo Tutora: Ana Sáez Hidalgo 4º Grado en Estudios Ingleses 2 Abstract Jonathan Swift has been considered one of the most skillful authors of the eighteenth century due to his harsh and accomplished satirist style of writing, and the polemic that it caused in the society of the time. His masterpiece, Gulliver’s Travels, an apparently simple travel book - among many others of the time- seems to camouflage, nevertheless, a brilliant satire that does not differ too much from the political essays and pamphlets published by the same author. In those writings, he harshly criticized the situation of his country by not only blaming Irish politicians and the British government, but also the own population and the stupidity of the human race. In this dissertation, I intend to find out about the author’s ideology through the study of the ideas captured in his literature. For this purpose, I have first analyzed four of Jonathan Swift’s political essays. Then, I have examined Gulliver’s Travels from the perspective of the conclusions reached through these first readings in order to expose the connection between Swift’s political treatises and his fiction. Key words: Jonathan Swift, politics, corruption, Gulliver’s Travels, government, Ireland, England Jonathan Swift es considerado uno de los mejores autores del siglo dieciocho debido a su conseguido estilo satírico y por la polémica que causó en la sociedad de su tiempo. -

Gulliver's Travels" Author(S): John Robert Moore Source: the Journal of English and Germanic Philology, Vol

The Geography of "Gulliver's Travels" Author(s): John Robert Moore Source: The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, Vol. 40, No. 2 (Apr., 1941), pp. 214-228 Published by: University of Illinois Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27704741 Accessed: 17-01-2020 16:44 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms University of Illinois Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of English and Germanic Philology This content downloaded from 117.240.50.232 on Fri, 17 Jan 2020 16:44:37 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms THE GEOGRAPHY OF GULLIVER'S TRAVELS I It is a commonplace that Gulliver's Travels is patterned after the real voyages of Swift's age, which it either travesties or imi tates. It lacks the supplement, describing the flora and fauna, so often appended to voyages; but it has the connecting links of detailed narrative, the solemn spirit of inquiry into strange lands, the factual records of latitude and coasts and prevailing winds, and (most of all) the maps. I have no quarrel with the present-day emphasis upon the philosophical background of Gulliver's Travels; that is a charac teristic contribution of the scholars of our generation. -

Gulliver's Travels

Gulliver's Travels Gulliver's Travels, or Travels into Several Remote Nations of Gulliver's Travels the World. In Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a Captain of Several Ships is a prose satire[1][2] of 1726 by the Irish writer and clergyman Jonathan Swift, satirising both human nature and the "travellers' tales" literary subgenre. It is Swift's best known full-length work, and a classic of English literature. Swift claimed that he wrote Gulliver's Travels "to vex the world rather than divert it". The book was an immediate success. The English dramatist John Gay remarked "It is universally read, from the cabinet council to the nursery."[3] In 2015, Robert McCrum released his selection list of 100 best novels of all time in which First edition of Gulliver's Travels [4] Gulliver's Travels is listed as "a satirical masterpiece". Author Jonathan Swift Original title Travels into Several Remote Nations of the Contents World. In Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Plot Surgeon, and then a Part I: A Voyage to Lilliput Captain of Several Ships Part II: A Voyage to Brobdingnag Country England Part III: A Voyage to Laputa, Balnibarbi, Luggnagg, Glubbdubdrib and Japan Language English Part IV: A Voyage to the Land of the Genre Satire, fantasy Houyhnhnms Publisher Benjamin Motte Composition and history Publication 28 October 1726 Faulkner's 1735 edition date Lindalino Media type Print Major themes Dewey 823.5 Misogyny Decimal Comic misanthropy Text Gulliver's Travels at Character analysis Wikisource Reception Cultural influences In other works Bibliography Editions See also References External links Online text Other Plot Part I: A Voyage to Lilliput The travel begins with a short preamble in which Lemuel Gulliver gives a brief outline of his life and history before his voyages. -

Gulliver's Travels - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

This is a digital copy of a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by Google as part of a project to make the world’s books discoverable online. It has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the book to enter the public domain. A public domain book is one that was never subject to copyright or whose legal copyright term has expired. Whether a book is in the public domain may vary country to country. Public domain books are our gateways to the past, representing a wealth of history, culture and knowledge that’s often difficult to discover. Marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume will appear in this file - a reminder of this book’s long journey from the publisher to a library and finally to you. Usage guidelines Google is proud to partner with libraries to digitize public domain materials and make them widely accessible. Public domain books belong to the public and we are merely their custodians. Nevertheless, this work is expensive, so in order to keep providing this resource, we have taken steps to prevent abuse by commercial parties, including placing technical restrictions on automated querying. We also ask that you: + Make non-commercial use of the files We designed Google Book Search for use by individuals, and we request that you use these files for personal, non-commercial purposes. + Refrain from automated querying Do not send automated queries of any sort to Google’s system: If you are conducting research on machine translation, optical character recognition or other areas where access to a large amount of text is helpful, please contact us. -

Reworkings in the Textual History of Gulliver's Travels: a Translational

Reworkings in the textual history of Gulliver’s Travels: a translational approach Alice Colombo The thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Portsmouth August 2013 ii ABSTRACT On 28 October 1726 Gulliver’s Travels debuted on the literary scene as a political and philosophical satire meant to provoke and entertain an audience of relatively educated and wealthy British readers. Since then, Swift’s work has gradually evolved, assuming multiple forms and meanings while becoming accessible and attractive to an increasingly broad readership in and outside Britain. My study emphasises that reworkings, including re-editions, translations, abridgments, adaptations and illustrations, have played a primary role in this process. Its principal aim is to investigate how reworkings contributed to the popularity of Gulliver’s Travels by examining the dynamics and the stages through which they transformed its text and its original significance. Central to my research is the assumption that this transformation is largely the result of shifts of a translational nature and that, therefore, the analysis of reworkings and the understanding of their role can greatly benefit from the models of translation description devised in Descriptive Translation Studies. The reading of reworkings as entailing processes of translation shows how derivative creations operate collaboratively to ensure literary works’ continuous visibility and actively shape the literary polysystem. The study opens with an exploration of existing approaches to reworkings followed by an examination of the characteristics which exposed Gulliver’s Travels to continuous rethinking and reworking. Emphasis is put on how the work’s satirical significance gave rise to a complex early textual problem for which Gulliver’s Travels can be said to have debuted on the literary scene as a derivative production in the first place. -

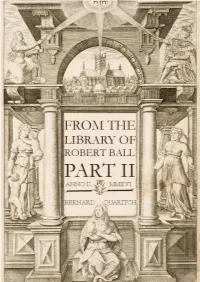

The Library of Robert Ball: Part Ii

BERNARD QUARITCH LTD. 40 SOUTH AUDLEY ST, LONDON W1K 2PR Tel: +44 (0)20-7297 4888 Fax: +44 (0)20-7297 4866 e-mail: [email protected] web site: www.quaritch.com Bankers: Barclays Bank plc, 50 Pall Mall, P.O. Box 15162, London SW1A 1QB Sort code: 20-65-82 Swift code: BARCGB22 Sterling account: IBAN: GB98 BARC 206582 10511722 Euro account: IBAN: GB30 BARC 206582 45447011 U.S. Dollar account: IBAN: GB46 BARC 206582 63992444 VAT number: GB 840 1358 54 MasterCard, Visa, and American Express accepted Recent Catalogues: 1433 English Books and Manuscripts 1432 Continental Books 1431 Travel & Exploration, Natural History Recent Lists: 2016/1 Human Sciences 2015/9 Early Drama 2015/8 Flora and Fauna 2015/7 Classics 2015/6 Design and Interiors 2015/5 Library of Robert Ball, Part I List 2016/2 Cover image from item 57. © Bernard Quaritch 2016 FROM THE LIBRARY OF ROBERT BALL: PART II English Literature 1500-1900, an American Journalist’s Collection Collecting rare books is a selfish pastime. It is about possession, about ownership. After all, the texts are universally available. Even the books themselves are often accessible in public libraries. But that is not the same as having them in one’s own bookcase. I have been an active collector for most of a long life. Now, in my 90th year, I have decided it is time to pass my pleasure on to others. Robert Ball 1) AUBREY, John. Miscellanies, viz. I. Day-Fatality. II. Local-Fatality. III. Ostenta. IV. Omens. V. Dreams. VI. Apparitions. VII. Voices. -

ORIGINAL RESEARCH PAPER Arunakumari S

PARIPEX - INDIAN JOURNAL OF RESEARCH | Volume - 10 | Issue - 06 |June - 2021 | PRINT ISSN No. 2250 - 1991 | DOI : 10.36106/paripex ORIGINAL RESEARCH PAPER English ECO-CRITICISM: HUMAN AND PHYSICAL WORLD RELATIONSHIP IN GULLIVER'S KEY WORDS: Sea, Animals, Race, and Landscapes TRAVELS. Assistant Professor, DWH-FLS, JSS Academy of Higher Education and Arunakumari S Research Mysore. This research paper studies a relationship between literature and the physical world is known as eco-criticism. In English Literature Eco criticism refers to specific types of texts. The word "Eco-criticism" depicts the images of nature, forests, animals, birds, seasons, rivers, cities, and flowers. In addition to novels, eco-criticism contains drama, poetry, travel books, cartoons, fables, short stories, movies, songs, games, children's stories and this is an Old English literature concept that's still trendy today, from Beowulf to the present writer. Animals have existed from the beginning of history. That means animals were depicted in literature since the start of history. When Christianity was introduced to the world, the Holy Bible says God created birds, animals first, at last man, it is called natural theology, and also nature is divine. CT Critics said, for western people's experience on earth is different from other people on the earth, Westerners believed in "Nature's uncountable sounds... have been deafening." The contrast, which is promoted by social anthropology of animism, highlights an element in contemporary society at large connection towards the physical world which is also gradually becoming a central focus when it comes to the environment."The natural world is a social and cultural ABSTRA category." In animistic traditions, those few who believe that perhaps the natural environment is inspirited, not only human beings, and also for life of animals, trees, and even "inert" entities like stones. -

THE ECONOMIC THEME in GULLIVER Is TRA VELS

Hitotsubashi Journal of Arts and Sciences 42 (2001), pp.41-58. C Hitotsubashi University THE ECONOMIC THEME IN GULLIVER iS TRA VELS KATSUMI HASHINUMA* In 1701 Lemuel Gulliver returns to England from Lilliput, after being rescued by an English merchantman on its way home from Japan, cruising north-east off Van Diemen's Land (or Tasmania on the modern map). Gulliver takes on board ten thousand Sprug coins and a portrait of the king of Lilliput, as well as live animals such as three hundred sheep, six cows, two bulls and as many ewes and rams, intending to "propagate the Breed." (GT, 66)1 He also wanted to take a dozen native Lilliputians but was unable to do so because of the king's injunction against their export. In less than ten months, before setting off on another voyage, he makes "a considerable Profit by showing [his] Cattle to many Persons of Quality, and others" and finally sells them for six hundred pounds (GT, 67). Later, returning from his final voyage, to the Houyhnhnm Land, Gulliver finds that "the Breed is considerably increased, especially the Sheep; which [he hopes] will prove much to the Advantage of the Woolen Manufacture, by the Fineness of the Fleeces" (GT, 68). His account of his Lilliputian sheep seems casual and irrelevant but it illustrates a point I wish to make in this article: that certain passages in Gulliver~ Travels, especially those in Part 111, become meaningful if looked at against the contemporary economic background. It is hardly surprising that Swift has something to say about economics, or "political economy" in the parlance of his age, in his most wide-ranging satire on European culture.