Towards a Theory of Cyclicality in English Funerary Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

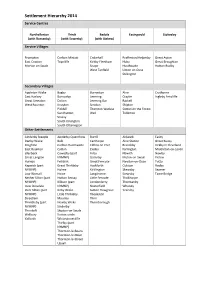

LDF05 Settlement Hierarchy (IPGN) 2014

Settlement Hierarchy 2014 Service Centres Northallerton Thirsk Bedale Easingwold Stokesley (with Romanby) (with Sowerby) (with Aiskew) Service Villages Brompton Carlton Miniott Crakehall Brafferton/Helperby Great Ayton East Cowton Topcliffe Kirkby Fleetham Huby Great Broughton Morton on Swale Snape Husthwaite Hutton Rudby West Tanfield Linton on Ouse Stillington Secondary Villages Appleton Wiske Bagby Burneston Alne Crathorne East Harlsey Borrowby Leeming Crayke Ingleby Arncliffe Great Smeaton Dalton Leeming Bar Raskelf West Rounton Knayton Scruton Shipton Pickhill Thornton Watlass Sutton on the Forest Sandhutton Well Tollerton Sessay South Kilvington South Otterington Other Settlements Ainderby Steeple Ainderby Quernhow Burrill Aldwark Easby Danby Wiske Balk Carthorpe Alne Station Great Busby Deighton Carlton Husthwaite Clifton on Yore Brandsby Kirkby in Cleveland East Rounton Catton Exelby Farlington Middleton-on-Leven Ellerbeck Cowesby (part Firby Flawith Newby Great Langton NYMNP) Gatenby Myton-on-Swale Picton Hornby Felixkirk Great Fencote Newton-on-Ouse Potto Kepwick (part Great Thirkleby Hackforth Oulston Rudby NYMNP) Holme Kirklington Skewsby Seamer Low Worsall Howe Langthorne Stearsby Tame Bridge Nether Silton (part Hutton Sessay Little Fencote Tholthorpe NYMNP) Kilburn (part Londonderry Thormanby Over Dinsdale NYMNP) Nosterfield Whenby Over Silton (part Kirby Wiske Sutton Howgrave Yearsley NYMNP) Little Thirkleby Theakston Streetlam Maunby Thirn Thimbleby (part Newby Wiske Thornborough NYMNP) Sinderby Thrintoft Skipton-on-Swale Welbury Sutton under Yafforth Whitestonecliffe Thirlby (part NYMNP) Thornton-le-Beans Thornton-le-Moor Thornton-le-Street Upsall . -

Converted from C:\PCSPDF\PCS65849.TXT

M197-6 PARISH COUNCIL ELECTION PARISH OF AINDERBY MIRES WITH HOLTBY __________________________________________ __________________________________________RESULT OF UN-CONTESTED ELECTION Date of Election : 1st May 2003 I, Peter Simpson, the Returning Officer at the above election do hereby certify that the name of the person(s) elected as Councillors for the said Parish without contest are as follows :- Name Address Description (if any) ANDERSON Ainderby Myers, Bedale, North Yorkshire, DL8 1PF CHRISTINE MARY WEBSTER Roundhill Farm, Hackforth, Bedale, DL8 1PB MARTIN HUGH Dated : 16th August 2011 PETER SIMPSON Returning Officer Printed and Published by the Returning Officer. L - NUC M197-6 PARISH COUNCIL ELECTION PARISH OF AISKEW AISKEW WARD __________________________________________ __________________________________________RESULT OF UN-CONTESTED ELECTION Date of Election : 1st May 2003 I, Peter Simpson, the Returning Officer at the above election do hereby certify that the name of the person(s) elected as Councillors for the said Parish Ward without contest are as follows :- Name Address Description (if any) LES Motel Leeming, Bedale, North Yorkshire, DL8 1DT CARL ANTHONY POCKLINGTON Windyridge, Aiskew, Bedale, North Yorks, DL8 1BA Sports Goods Retailer ROBERT Dated : 16th August 2011 Peter Simpson Returning Officer Printed and Published by the Returning Officer. L - NUC M197-6 PARISH COUNCIL ELECTION PARISH OF AISKEW LEEMING BAR WARD __________________________________________ __________________________________________RESULT OF UN-CONTESTED ELECTION Date of Election : 1st May 2003 I, Peter Simpson, the Returning Officer at the above election do hereby certify that the name of the person(s) elected as Councillors for the said Parish Ward without contest are as follows :- Name Address Description (if any) Dated : 16th August 2011 Peter Simpson Returning Officer Printed and Published by the Returning Officer. -

(Electoral Changes) Order 2000

545297100128-09-00 23:35:58 Pag Table: STATIN PPSysB Unit: PAG1 STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2000 No. 2600 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The District of Hambleton (Electoral Changes) Order 2000 Made ----- 22nd September 2000 Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) Whereas the Local Government Commission for England, acting pursuant to section 15(4) of the Local Government Act 1992(a), has submitted to the Secretary of State a report dated November 1999 on its review of the district of Hambleton together with its recommendations: And whereas the Secretary of State has decided to give effect to those recommendations: Now, therefore, the Secretary of State, in exercise of the powers conferred on him by sections 17(b) and 26 of the Local Government Act 1992, and of all other powers enabling him in that behalf, hereby makes the following Order: Citation, commencement and interpretation 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the District of Hambleton (Electoral Changes) Order 2000. (2) This Order shall come into force— (a) for the purposes of proceedings preliminary or relating to any election to be held on 1st May 2003, on 10th October 2002; (b) for all other purposes, on 1st May 2003. (3) In this Order— “district” means the district of Hambleton; “existing”, in relation to a ward, means the ward as it exists on the date this Order is made; any reference to the map is a reference to the map prepared by the Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions marked “Map of the District of Hambleton (Electoral Changes) Order 2000”, and deposited in accordance with regulation 27 of the Local Government Changes for England Regulations 1994(c); and any reference to a numbered sheet is a reference to the sheet of the map which bears that number. -

Areas Designated As 'Rural' for Right to Buy Purposes

Areas designated as 'Rural' for right to buy purposes Region District Designated areas Date designated East Rutland the parishes of Ashwell, Ayston, Barleythorpe, Barrow, 17 March Midlands Barrowden, Beaumont Chase, Belton, Bisbrooke, Braunston, 2004 Brooke, Burley, Caldecott, Clipsham, Cottesmore, Edith SI 2004/418 Weston, Egleton, Empingham, Essendine, Exton, Glaston, Great Casterton, Greetham, Gunthorpe, Hambelton, Horn, Ketton, Langham, Leighfield, Little Casterton, Lyddington, Lyndon, Manton, Market Overton, Martinsthorpe, Morcott, Normanton, North Luffenham, Pickworth, Pilton, Preston, Ridlington, Ryhall, Seaton, South Luffenham, Stoke Dry, Stretton, Teigh, Thistleton, Thorpe by Water, Tickencote, Tinwell, Tixover, Wardley, Whissendine, Whitwell, Wing. East of North Norfolk the whole district, with the exception of the parishes of 15 February England Cromer, Fakenham, Holt, North Walsham and Sheringham 1982 SI 1982/21 East of Kings Lynn and the parishes of Anmer, Bagthorpe with Barmer, Barton 17 March England West Norfolk Bendish, Barwick, Bawsey, Bircham, Boughton, Brancaster, 2004 Burnham Market, Burnham Norton, Burnham Overy, SI 2004/418 Burnham Thorpe, Castle Acre, Castle Rising, Choseley, Clenchwarton, Congham, Crimplesham, Denver, Docking, Downham West, East Rudham, East Walton, East Winch, Emneth, Feltwell, Fincham, Flitcham cum Appleton, Fordham, Fring, Gayton, Great Massingham, Grimston, Harpley, Hilgay, Hillington, Hockwold-Cum-Wilton, Holme- Next-The-Sea, Houghton, Ingoldisthorpe, Leziate, Little Massingham, Marham, Marshland -

Cedar House, 3 Endican Lane Thornton Le Moor, Northallerton, DL7 9FB

Cedar House, 3 Endican Lane Thornton Le Moor, Northallerton, DL7 9FB Cedar House, 3 Endican Lane Thornton Le Moor Northallerton DL7 9FB Guide Price: £420,000 Impressive Detached House of individual design Well appointed and extremely spacious family accommodation Five Double Bedrooms, Bathroom and en suite Shower Room Gardens to front and rear and integral Detached Garage Youngs - Northallerton 01609 773004 DESCRIPTION Cedar House is an impressive Detached House of The Accommodation Comprises cupboard below, wood flooring, door into garage, two radiators, individual design built circa 2000 and occupying a delightful glazed double doors opening to: setting in a small cul de sac of just five properties on the fringe of GROUND FLOOR this popular village. Thornton le Moor lies approximately five Large Conservatory 13' 8'' x 11' 6'' (4.16m x 3.50m) With sealed miles south of Northallerton off the A168 Thirsk road with easy Entrance Hall With window to side and part glazed front door, unit double glazed windows on brick plinth, ceramic tiled floor, access to both towns and also the A1 and A19 roads for easy ceramic tiled floor, radiator, inset ceiling lights. Stairs to first floor double doors to rear garden. access to major centres. It also lies just a short distance from the with store cupboard below. North York Moors which afford some of the region's most FIRST FLOOR spectacular scenery together with a wide range of leisure Cloakroom/WC With white suite comprising close coupled WC pursuits. The highly regarded South Otterington primary school is and wash basin with tiled splashback, ceramic tiled floor, radiator. -

Mr Paul Vayro 10 Beechfield, South Otterington, North Yorkshire, DL7 9JJ

Mr Paul Vayro 10 Beechfield, South Otterington, North Yorkshire, DL7 9JJ. Date: 20th November 2017 F.A.O. Diane Parsons North Yorkshire Police & Crime Commission c/o County Hall, Racecourse Lane, Northallerton, North Yorkshire, DL7 8AD. Dear Sirs RE: Sale of Newby Wiske Hall to PGL Travel Ltd I write again regarding the above planned sale to PGL, after attending last Thursdays NYPCC public Q & A forum in York, I am even more disgusted, with NYPCC who are after all supposed to uphold and represent the moral fibre of our society. Following the points made by Mr David Stockport, you would have thought that at least there would have been an acceptance of the points made; instead the Chairman was so indignant to the fact, that someone should dare to suggest that a public body should show even a modicum of moral fibre, in the respect of the Paradise Papers, and the massive negative effect these schemes have on Public Finances and Services, instead the response by the Chairman was, its nothing to do with us, so let’s move on. I repeat, this company are so heavily and extensively involved in a scheme to avoid paying tax in the UK, they receive tax handouts for listed buildings, significant Government subsidies for assisted places (This would be perfectly acceptable if they paid their full taxes to the UK Government), only then to operate a tax avoidance scheme, meaning we, the British tax payer, would be helping them pay even less tax, which could be used to support ALL OUR UNDERFUNDED PUBLIC SERVICES including the POLICE. -

Stainthorpe Row, South Otterington

Residential Development on land at Stainthorpe Row, South Otterington August 2020 Contents 01 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 02 SITE INTRODUCTION 4 03 SITE ANALYSIS 8 04 LANDSCAPE AND VISUAL ANALYSIS 10 05 SCHEMATIC DEVELOPMENT PROPOSALS 12 06 SUMMARY AND BENEFITS 14 1771111111111 01. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This promotional document has been prepared to highlight the suitability and availability of land at Stainthorpe Row, South Otterington. In particular it will highlight the level of services and facilities already in the locality which contribute to making the site sustainable. A desk based assessment has been adopted to establish the constraints and opportunities for the site. This has informed the production of an indicative masterplan to show how the site could be laid out and to demonstrate that a high quality housing development can be comfortably integrated within the surrounding area. It is considered that the site detailed in this report would make an ideal location for residential development and would accord with the Framework on Housing in the following regard: Available – The whole of the site is available now; Suitable – The site is in a sustainable location and is well related to the existing built form; Achievable – Delivery of housing and employment can be achieved within 5 years. Overall this report demonstrates that the site can be considered to be both deliverable and a viable location for future housing development. VISION FOR THE DEVELOPMENT The Vision for the site is to provide a high quality residential led development which fully considers the existing constraints and takes advantage of the potential opportunities of the site. -

LAND at KIRBY WISKE Thirsk, North Yorkshire LAND at KIRBY WISKE THIRSK, NORTH YORKSHIRE, YO7 4DH

LAND AT KIRBY WISKE Thirsk, North Yorkshire LAND AT KIRBY WISKE THIRSK, NORTH YORKSHIRE, YO7 4DH Kirby Wiske 1 mile Thirsk 5 miles Northallerton 6 miles A HIGHLY PRODUCTIVE BLOCK OF PREDOMINANTLY GRADE 2 ARABLE LAND WITH EXCELLENT ACCESS AND VERSATILE CROPPING OPTIONS. ABOUT 131.44 ACRES (53.19 HA) For sale as a whole 5 & 6 Bailey Court, Colburn Business Park, North Yorkshire, DL9 4QL Tel: 01748 897610 www.gscgrays.co.uk [email protected] Offices also at: Alnwick Chester-le-Street Colburn Easingwold Tel: 01665 568310 Tel: 0191 303 9540 Tel: 01748 897610 Tel: 01347 837100 Hamsterley Hexham Leyburn Stokesley Tel: 01388 487000 Tel: 01434 611565 Tel: 01969 600120 Tel: 01642 710742 METHOD OF SALE The land is offered for sale by private treaty. All potential purchasers are advised to register their interest with the Selling Agents so that they can be advised as to how the sale will be concluded. TENURE The property is to be sold freehold with vacant possession. SPORTING RIGHTS The sporting rights are included in the sale in so far as they are owned. MINERAL RIGHTS The mineral rights are included in the sale in so far as they are owned. WAYLEAVES, EASEMENTS AND RIGHTS OF WAY There is a right of way along the track within the southern field parcels to which the purchaser will be required to contribute 60% of the reasonable cost of keeping it in a reasonable state and condition. Two public footpaths cross the property at either end. DESCRIPTION Further details can be seen on the North Yorkshire Public The land at Kirby Wiske comprises approximately 131.44 acres and 30m above sea level. -

Community News

COMMUNITY NEWS KIRBY WISKE, MAUNBY, NEWBY WISKE & SOUTH OTTERINGTON Search - South Otterington, Maunby, Kirby Wiske and Newby Wiske Community WHAT’S ON IN FEBRUARY 2019 Winter Specials at the Otterington Shorthorn – buy 1 meal and get a second ½ price for the Winter Specials Board. Served Tuesday to Saturday (offer ends 28th Feb) Fri 1st Six Nations Rugby at The Otterington Shorthorn. Kick Off at 8pm France v Wales Sat 2nd from 7.30pm The Big Swing Defibrillator Fundraiser at The Buck Inn, Maunby - swing music, dining & dancing; speak easy Cocktail bar in aid of the Defibillator Fund Evening Tickets - £5, Dining Tickets £20. There will be a courtesy bus available from South Otterington & Newby Wiske, in order to book your space on the bus please telephone the pub on 01845 587777 – it may be a shuttle bus, so we would like to be able to advise people accurately when the pick-ups will be Sat 2nd Six Nations Rugby at The Otterington Shorthorn. Kick off 4.45pm Ireland v England. Half time snacks available Thurs 7th between 10-11.30am Book Exchange, Coffee Morning & Raffle at South Otterington Village Hall with freshly baked & homemade cakes, scones & biscuits Thurs 7th 7.30pm Winter Quiz at The Buck Inn, Maunby hosted by Ken & Cathy. All funds raised from the winter quizzes are going to the 3 villages Defibrillator fund Fri 8th 7pm Family Beetle Drive at Kirby Wiske Village Hall. As usual, a hot baked potato with a variety of fillings will be included in the price. Tickets £6, £4 under 16yrs Fri 8th Wine and Cheese tasting at Thief Hall, back by popular demand after a 3- year absence Sun 10th Six Nations Rugby at The Otterington Shorthorn. -

Garthlea South Otterington, Northallerton Dl7 9Hu

GARTHLEA SOUTH OTTERINGTON, NORTHALLERTON DL7 9HU A SUPERBLY POSITIONED SUBSTANTIAL BUNGALOW RESIDENCE SITUATED ON A LARGE PLOT WITH TREMENDOUS SCOPE FOR DEVELOPMENT AND IN NEED OF FULL UPDATING AND MODERNISATION SUBJECT TO PURCHASER’S REQUIREMENTS AND THE NECESSARY PLANNING PERMISSIONS. • 2 – 3 Bed Detached Bungalow • Tremendous Views over Countryside • Turning Circle & Gardens to Front • UPVC Sealed Unit DG & Oil Central Heating • Large Rear Lawned Garden • Tremendous Scope for Extension subject to PP Offers in the region of: £250,000 143 High Street, Northallerton, DL7 8PE Tel: 01609 771959 Fax: 01609 778500 www.northallertonestateagency.co.uk GARTHLEA, SOUTH OTTERINGTON DL7 9HU SITUATION within easy reach of the North Yorkshire Moors and the Yorkshire Dales and close to good local rivers and ponds. Northallerton 4 miles Ripon 12 miles Thirsk 7 miles A1 8 miles Racing – Catterick, Thirsk, York, Sedgefield, Redcar, Ripon, A19 10 miles Darlington 20 miles Beverley and Doncaster. York 30 miles Leeds 40 miles (All distances are approximate) Golf - Romanby (Northallerton), Thirsk, Darlington, Bedale, Richmond and Catterick This substantial detached dormer bungalow residence is very attractively situated, nicely set back from the A.167 just outside Walking – the area is well served for attractive walking and the centre of the much sought after and highly desirable North cycling with some particularly attractive countryside and scenery Yorkshire Village of South Otterington. The property enjoys a situated around the property. particularly attractive position being nicely set back from the road through the village but additionally having tremendous Theatres – Darlington, Richmond, Durham, Newcastle and York views to the rear over attractive open countryside. -

Community News

COMMUNITY NEWS KIRBY WISKE, MAUNBY, NEWBY WISKE & OTTERINGTON’S Search - South Otterington, Maunby, Kirby Wiske and Newby Wiske Community WHAT’S ON IN FEBRUARY 2020 Thu 6th 10.00 to 11.30am Coffee morning and Book Exchange at South Otterington Village Hall. Come and get yourself a nice book to read and have a cup of coffee, a piece of cake, a chance at the raffle and a good chat. Thu 6th 7.30 Talk by John Buglass “Secrets of the Yorkshire Coast” entrance fee £4.00 in aid of the Newby Wiske Action Fund, please support this as we will all be affected if PGL win. Come and hear John’s very interesting talk. Fri 28th 7.30pm Call my Bluff Wine Evening, South Otterington Village Hall, tickets are £10 and need to be booked in advance, you can get them from Vanessa Gillson on 07980 885664 or Patricia Shore on 07872 875 777. All proceeds made will be in aid of the Village Hall toilet refurbishment. South Otterington, Newby Wiske & Maunby Parish Council Details of current Parish Council members & their contact details can be found on Public Notice Boards in each village. Any other queries contact Keith Bowe on 07557 798386. The Parish Council has a small pot of funds from the Community Infrastructure Levy that can be used for Parish Projects, if you have any ideas of projects in your village please let Keith Holliday (Olly) or Ken Johnson (Maunby); Vanessa Gillson or Celia Newton (Otterington’s); Iain Glover or Keith Bowe (Newby Wiske) know, their details are on the village notice boards. -

Community News

COMMUNITY NEWS KIRBY WISKE, MAUNBY, NEWBY WISKE & OTTERINGTON’S Search - South Otterington, Maunby, Kirby Wiske and Newby Wiske Community WHAT’S ON IN NOVEMBER 2019 Fri 1st Halloween fancy dress party & karaoke at The Otterington Shorthorn, please join in the fun and come dressed up! Tues 5th from 6.30pm Maunby bonfire and fireworks to find us go to the bottom of village past the green, along the track on the right-hand side or simply follow the crowd!! Winter warmers (hot hogs and soup) available and donations welcome (penny for the guy). The Buck Inn is doing woodfired pizzas at the back of the pub and is open for refreshments after the display, everyone welcome Thurs 7th between 10-11.30am Book Exchange, Coffee Morning & Raffle in Village Hall at South Otterington Fri 8th 7.30pm Harvest Festival Ceilidh in Village Hall at South Otterington with pie supper. Advance tickets only, see below for further details Fri 8th Acoustic Open Mic Night from 8.30pm at The Buck Inn, Maunby. All abilities welcome or just come along for the social Fri 12th 7pm Kirby Wiske Local History Group meeting in Kirby Wiske Village Hall. Members will be discussing and collating information relating to the Methodist Chapel gleaned at our last meeting Fri 22nd 7.30pm Folk Evening in Aid of the Newby Wiske Action Group in Village Hall at South Otterington further information available from Carol Bowes Fri 22nd 8pm Fun Quiz and Bingo night at The Buck Inn, Maunby Thurs 21st 7.30pm Parish Council Meeting in Village Hall at South Otterington Fri 29th 7.30pm Kirby Wiske Wine tasting Call My Bluff at Kirby Wiske Village Hall SNEAK PEEK AT FUTURE EVENTS Sun 1st Dec Friends of South Otterington School, Christmas Fair, in Village Hall at South Otterington Thurs 5th Dec Book Exchange, Coffee Morning & Raffle in Village Hall at South Otterington Tues 10th Dec Kirby Wiske Local History Group Christmas Lunch at The Crosby, Thornton le Beans Tues 14th Jan Kirkby Wiske Local History Group we will be hearing about Kirby Wiske during WW1 from visitors Eileen Brereton and Ann Ward.