Metrical Structure and Freedom in Qin Music of the Chinese Literati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December 1992

VOLUME 16, NUMBER 12 MASTERS OF THE FEATURES FREE UNIVERSE NICKO Avant-garde drummers Ed Blackwell, Rashied Ali, Andrew JEFF PORCARO: McBRAIN Cyrille, and Milford Graves have secured a place in music history A SPECIAL TRIBUTE Iron Maiden's Nicko McBrain may by stretching the accepted role of When so respected and admired be cited as an early influence by drums and rhythm. Yet amongst a player as Jeff Porcaro passes metal drummers all over, but that the chaos, there's always been away prematurely, the doesn't mean he isn't as vital a play- great discipline and thought. music—and our lives—are never er as ever. In this exclusive interview, Learn how these free the same. In this tribute, friends find out how Nicko's drumming masters and admirers share their fond gears move, and what's tore down the walls. memories of Jeff, and up with Maiden's power- • by Bill Milkowski 32 remind us of his deep ful new album and tour. 28 contributions to our • by Teri Saccone art. 22 • by Robyn Flans THE PERCUSSIVE ARTS SOCIETY For thirty years the Percussive Arts Society has fostered credibility, exposure, and the exchange of ideas for percus- sionists of every stripe. In this special report, learn where the PAS has been, where it is, and where it's going. • by Rick Mattingly 36 MD TRIVIA CONTEST Win a Sonor Force 1000 drumkit—plus other great Sonor prizes! 68 COVER PHOTO BY MICHAEL BLOOM Education 58 ROCK 'N' JAZZ CLINIC Back To The Dregs BY ROD MORGENSTEIN Equipment Departments 66 BASICS 42 PRODUCT The Teacher Fallacy News BY FRANK MAY CLOSE-UP 4 EDITOR'S New Sabian Products OVERVIEW BY RICK VAN HORN, 8 UPDATE 68 CONCEPTS ADAM BUDOFSKY, AND RICK MATTINGLY Tommy Campbell, Footwork: 6 READERS' Joel Maitoza of 24-7 Spyz, A Balancing Act 45 Yamaha Snare Drums Gary Husband, and the BY ANDREW BY RICK MATTINGLY PLATFORM Moody Blues' Gordon KOLLMORGEN Marshall, plus News 47 Cappella 12 ASK A PRO 90 TEACHERS' Celebrity Sticks BY ADAM BUDOFSKY 146 INDUSTRY FORUM AND WILLIAM F. -

Voyager's Gold Record

Voyager's Gold Record https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voyager_Golden_Record #14 score, next page. YouTube (Perlman): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aVzIfSsskM0 Each Voyager space probe carries a gold-plated audio-visual disc in the event that the spacecraft is ever found by intelligent life forms from other planetary systems.[83] The disc carries photos of the Earth and its lifeforms, a range of scientific information, spoken greetings from people such as the Secretary- General of the United Nations and the President of the United States and a medley, "Sounds of Earth," that includes the sounds of whales, a baby crying, waves breaking on a shore, and a collection of music, including works by Mozart, Blind Willie Johnson, Chuck Berry, and Valya Balkanska. Other Eastern and Western classics are included, as well as various performances of indigenous music from around the world. The record also contains greetings in 55 different languages.[84] Track listing The track listing is as it appears on the 2017 reissue by ozmarecords. No. Title Length "Greeting from Kurt Waldheim, Secretary-General of the United Nations" (by Various 1. 0:44 Artists) 2. "Greetings in 55 Languages" (by Various Artists) 3:46 3. "United Nations Greetings/Whale Songs" (by Various Artists) 4:04 4. "The Sounds of Earth" (by Various Artists) 12:19 "Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F Major, BWV 1047: I. Allegro (Johann Sebastian 5. 4:44 Bach)" (by Munich Bach Orchestra/Karl Richter) "Ketawang: Puspåwårnå (Kinds of Flowers)" (by Pura Paku Alaman Palace 6. 4:47 Orchestra/K.R.T. Wasitodipuro) 7. -

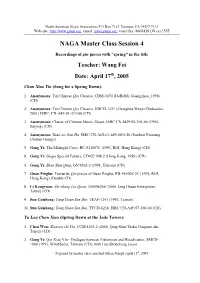

A List of Qin Recordings with a Spring Theme

North American Guqin Association, P O Box 7113, Fremont, CA 94537-7113 Web site: http://www.guqin.org, email: [email protected], voice/fax: 8668419139 ext 1555 NAGA Master Class Session 4 Recordings of qin pieces with “spring” in the title Teacher: Wang Fei Date: April 17th, 2005 Chun Xiao Yin (Song for a Spring Dawn): 1. Anonymous: Ten Chinese Qin Classics, CDM-1074 (DoReMi, Guangzhou, 1998) (CD) 2. Anonymous: Ten Chinese Qin Classics, HDCD-1121 (Zhonghua Wenyi Chubanshe, 2001) ISRC: CN-A49-01-313-00 (CD) 3. Anonymous: Classic of Chinese Music: Guqin, ISRC CN-M29-94-306-00 (1994, Beijing) (CD) 4. Anonymous: Xiao’ao Jian Hu, ISRC CN-A65-01-649-00/A.J6 (Jiuzhou Yinxiang Chuban Gongsi) 5. Gong Yi: The Midnight Crow, RC-931007C (1993, ROI, Hong Kong) (CD) 8. Gong Yi: Guqin Special Feature, CD422 998-2 (Hong Kong, 1989) (CD) 6. Gong Yi: Shan Shui Qing, GN 9202-2 (1991, Taiwan) (CD) 7. Guan Pinghu: Favourite Qin pieces of Guan Pinghu, RB-951005-2C (1995, ROI, Hong Kong) (Double CD) 8. Li Kongyuan: Shi-shang Liu Quan, 200098268 (2000, Ling Hsuan Enterprises, Taibei) (CD) 9. Sun Guisheng: Yang Guan San Die, JRAF-1241 (1992, Taiwan) 10. Sun Guisheng: Yang Guan San Die, TYCD-0238, ISRC CN-A49-97-360-00 (CD) Yu Lou Chun Xiao (Spring Dawn at the Jade Tower): 1. Chen Wen: Xianwai zhi Yin, CCM 8103-2 (2000, Qing Shan Yishu Gongzuo-shi, Taipei) (CD) 2. Gong Yi: Qin Xiao Yin - Dialogue between Fisherman and Wood-cutter, SMCD- 1008 (1995, Wind/Solar, Taiwan) (CD); with Luo Shoucheng (xiao) Prepared by master class assistant Julian Joseph April 15th, 2005 North American Guqin Association, P O Box 7113, Fremont, CA 94537-7113 Web site: http://www.guqin.org, email: [email protected], voice/fax: 8668419139 ext 1555 3. -

Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: the Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa

STYLISTIC EVOLUTION OF JAZZ DRUMMER ED BLACKWELL: THE CULTURAL INTERSECTION OF NEW ORLEANS AND WEST AFRICA David J. Schmalenberger Research Project submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Percussion/World Music Philip Faini, Chair Russell Dean, Ph.D. David Taddie, Ph.D. Christopher Wilkinson, Ph.D. Paschal Younge, Ed.D. Division of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2000 Keywords: Jazz, Drumset, Blackwell, New Orleans Copyright 2000 David J. Schmalenberger ABSTRACT Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: The Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa David J. Schmalenberger The two primary functions of a jazz drummer are to maintain a consistent pulse and to support the soloists within the musical group. Throughout the twentieth century, jazz drummers have found creative ways to fulfill or challenge these roles. In the case of Bebop, for example, pioneers Kenny Clarke and Max Roach forged a new drumming style in the 1940’s that was markedly more independent technically, as well as more lyrical in both time-keeping and soloing. The stylistic innovations of Clarke and Roach also helped foster a new attitude: the acceptance of drummers as thoughtful, sensitive musical artists. These developments paved the way for the next generation of jazz drummers, one that would further challenge conventional musical roles in the post-Hard Bop era. One of Max Roach’s most faithful disciples was the New Orleans-born drummer Edward Joseph “Boogie” Blackwell (1929-1992). Ed Blackwell’s playing style at the beginning of his career in the late 1940’s was predominantly influenced by Bebop and the drumming vocabulary of Max Roach. -

Increasing the Use of Multicultural Education in a Preschool Located in a Homogeneous Midwest Community

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 415 008 PS 026 058 AUTHOR Hartke, Cheryl L. TITLE Increasing the Use of Multicultural Education in a Preschool Located in a Homogeneous Midwest Community. PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 339p.; Master's Practicum Report, Nova Southeastern University. Many pages in appendices contain small print and photos and may not reproduce well. PUB TYPE Dissertations/Theses - Practicum Papers (043) Reports Evaluative (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC14 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Class Activities; Classroom Environment; Course Content; *Cultural Activities; *Cultural Awareness; Cultural Pluralism; Curriculum Development; Curriculum Enrichment; *Day Care; Day Care Centers; *Homogeneous Grouping; Instructional Development; *Multicultural Education; *Preschool Education; Program Effectiveness IDENTIFIERS Multicultural Materials ABSTRACT The inclusion of multicultural education in the curriculum of child care centers is becoming a necessity, particularly in homogeneous communities, as the ethnic make-up of society continues to change. This practicum project implemented and evaluated a strategy intended to increase the use of multicultural education in a middle-to-upper-class suburban child care center with 92 percent Caucasian enrollment. The strategy involved a four-part process: development of resource lists, exploration of teachers' attitudes, improvement of multicultural materials available for use, and increase in teachers' knowledge about diversity, with information provided during weekly meetings. Post-intervention data indicated that, overall, the use of multicultural education in the center increased. Teachers included multicultural activities in all areas of the curriculum on a regular basis, and more materials were available for classroom use as a result of parent donations and the development of a resource room. (Seventeen appendices include an anti-bias checklist, book checklist, a list of broad goals of teaching from a multicultural perspective, and an array of multicultural materials. -

Master's Recital in Jazz Pedagogy

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Dissertations and Theses @ UNI Student Work 2019 Master's recital in jazz pedagogy: A performance-demonstration of rhythm section instruments, trumpet, electric wind instrument, synthesizer, compositions, and arrangements by DeMetrio Lyle DeMetrio Lyle University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©2019 DeMetrio Lyle Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd Part of the Composition Commons, and the Music Pedagogy Commons Recommended Citation Lyle, DeMetrio, "Master's recital in jazz pedagogy: A performance-demonstration of rhythm section instruments, trumpet, electric wind instrument, synthesizer, compositions, and arrangements by DeMetrio Lyle" (2019). Dissertations and Theses @ UNI. 997. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/997 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses @ UNI by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MASTER’S RECITAL IN JAZZ PEDAGOGY: A PERFORMANCE-DEMONSTRATION OF RHYTHM SECTION INSTRUMENTS, TRUMPET, ELECTRIC WIND INSTRUMENT, SYNTHESIZER, COMPOSITIONS, AND ARRANGEMENTS BY DEMETRIO LYLE An Abstract of a Recital Submitted In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree Master of Music in Jazz Pedagogy DeMetrio Lyle University of Northern Iowa December 2019 This Recital Abstract by: DeMetrio Lyle Entitled: Master’s Recital in Jazz Pedagogy: A Performance-Demonstration of Rhythm Section Instruments, Trumpet, Electric Wind Instrument, Synthesizer, Compositions, and Arrangements by DeMetrio Lyle Has been approved as meeting the thesis requirement for the Degree of Master of Music Jazz Pedagogy Date Prof. -

The Equality of Kowtow: Bodily Practices and Mentality of the Zushiye Belief

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo Journal of Cambridge Studies 1 The Equality of Kowtow: Bodily Practices and Mentality of the Zushiye Belief Yongyi YUE Beijing Normal University, P.R. China Email: [email protected] Abstract: Although the Zushiye (Grand Masters) belief is in some degree similar with the Worship of Ancestors, it obviously has its own characteristics. Before the mid-twentieth century, the belief of King Zhuang of Zhou (696BC-682BC), the Zushiye of many talking and singing sectors, shows that except for the group cult, the Zushiye belief which is bodily practiced in the form of kowtow as a basic action also dispersed in the group everyday life system, including acknowledging a master (Baishi), art-learning (Xueyi), marriage, performance, identity censorship (Pandao) and master-apprentice relationship, etc. Furthermore, the Zushiye belief is not only an explicit rite but also an implicit one: a thinking symbol of the entire society, special groups and the individuals, and a method to express the self and the world in inter-group communication. The Zushiye belief is not only “the nature of mind” or “the mentality”, but also a metaphor of ideas and eagerness for equality, as well as relevant behaviors. Key Words: Belief, Bodily practices, Everyday life, Legends, Subjective experience Yongyi YUE, Associate Professor, Folklore and Cultural Anthropology Institute, College of Chinese Language and Literature, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, 100875, PRC Volume -

Identification of Bile Salt Hydrolase Inhibitors, the Promising Alternative to Antibiotic Growth Promoters to Enhance Animal Production

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2013 Identification of bile salt hydrolase inhibitors, the promising alternative to antibiotic growth promoters to enhance animal production Katie Rose Smith [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Animal Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Katie Rose, "Identification of bile salt hydrolase inhibitors, the promising alternative to antibiotic growth promoters to enhance animal production. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2013. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/2457 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Katie Rose Smith entitled "Identification of bile salt hydrolase inhibitors, the promising alternative to antibiotic growth promoters to enhance animal production." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Animal Science. Jun Lin, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: John C. Waller, Michael O. Smith, Niki Labbe Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Identification of bile salt hydrolase inhibitors, the promising alternative to antibiotic growth promoters to enhance animal production A Thesis Presented for the Master of Science Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Katie Rose Smith August 2013 DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to Dr. -

![[Ton]Spurensuche : Ernst Bloch Und Die Musik](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5658/ton-spurensuche-ernst-bloch-und-die-musik-1175658.webp)

[Ton]Spurensuche : Ernst Bloch Und Die Musik

Klappe hinten U4 U4 Buchrücken U1 U1 Klappe vorne KOLLEKTION MUSIKWISSENSCHAFT KOLLEKTION MUSIKWISSENSCHAFT MATTHIAS HENKE KOLLEKTION MUSIKWISSENSCHAFT HERAUSGEGEBEN VON MATTHIAS HENKE HERAUSGEGEBEN VON MATTHIAS HENKE HERAUSGEGEBEN VON MATTHIAS HENKE BAND 1 FRANCESCA VIDAL (HG.) BAND 1 MATTHIAS HENKE, FRANCESCA VIDAL (HG.) Matthias Henke, Francesca Vidal (Hg.) TON SPURENSUCHE Si! – das Motto der Kollektion Musikwissen- [Ton]Spurensuche [ ] ERNST BLOCH UND DIE MUSIK [TON]SPURENSUCHE schaft ist vielfältig. Zunächst spielt es auf Ernst Bloch und die Musik die Basis der Buchreihe an, den Universi- tätsverlag Siegen. Si! meint aber auch ein musikalisches Phänomen, heißt so doch der Spuren – so ist nicht nur ein Band mit den poetisch ver- Leitton einer Durskala. Last, not least will Ankündigung: trackten Erzählungen von Ernst Bloch überschrieben. FRANCESCA (HG.) VIDAL | Si! sich als Imperativ verstanden wissen, als [Ton]Spuren durchwirken vielmehr sein gesamtes Werk. ERNST BLOCH BAND 2 ein vernehmbares Ja zu einer Musikwissen- Demnach erstaunt es nicht, wenn des Philosophen Ver- Sara Beimdieke schaft, die sich zu dem ihr eigenen Potential hältnis zur Musik vielfach Gegenstand wissenschaftlicher „Der große Reiz des Kamera-Mediums“ UND DIE MUSIK bekennt, zu einer selbstbewussten Diszipli- Erörterungen war. Allerdings näherte man sich diesem Ernst Kreneks Fernsehoper Ausgerech- narität, die wirkliche Trans- oder Interdiszip- fast immer auf Metaebenen. Philologische Detailarbeit, net und Verspielt linarität erst ermöglicht. die etwa die Genesis -

Study on the Guqin Teaching Method: “Inner Understanding Through Oral Teaching”

Open Journal of Social Sciences, 2019, 7, 138-146 http://www.scirp.org/journal/jss ISSN Online: 2327-5960 ISSN Print: 2327-5952 Study on the Guqin Teaching Method: “Inner Understanding through Oral Teaching” Ye Zhao Conservatory of Music, Nanjing Normal University, Nanjing, China How to cite this paper: Zhao, Y. (2019) Abstract Study on the Guqin Teaching Method: “In- ner Understanding through Oral Teaching”. “Inner understanding through oral teaching” is the main teaching method Open Journal of Social Sciences, 7, 138-146. that runs through Guqin for thousands of years. In order to inherit and pro- https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2019.72011 tect traditional Guqin art originally in the modern society, it’s very important Received: January 12, 2019 to research this method which is used to teach Guqin in the ancient. It con- Accepted: February 16, 2019 sists of two teaching levels: “Oral” and “Mentality”: the combination of the Published: February 19, 2019 two promotes the inheritance and development of traditional Guqin. The teaching method of “inner understanding through oral teaching” is closely Copyright © 2019 by author(s) and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. related to the application of the word reduction spectrum, and it is not con- This work is licensed under the Creative tradictory to “viewing teaching”. In the current society, “inner understanding Commons Attribution International through oral teaching” is of great significance to the protection and inherit- License (CC BY 4.0). ance of Guqin. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Open Access Keywords Inner Understanding through Oral Teaching, Guqin 1. What Is the Connotation of the “Inner Understanding through Oral Teaching” “Inner understanding through oral teaching” is a teaching method formed under certain historical conditions and social and humanistic environment. -

Educating Through Music from an "Initiation Into Classical Music" for Children to Confucian "Self- Cultivation" for University Students

China Perspectives 2008/3 | 2008 China and its Continental Borders Educating Through Music From an "Initiation into Classical Music" for Children to Confucian "Self- Cultivation" for University Students Zhe Ji Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/4133 DOI: 10.4000/chinaperspectives.4133 ISSN: 1996-4617 Publisher Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 1 July 2008 Number of pages: 107-117 ISSN: 2070-3449 Electronic reference Zhe Ji, « Educating Through Music », China Perspectives [Online], 2008/3 | 2008, Online since 01 July 2011, connection on 28 October 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/4133 ; DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.4133 © All rights reserved Articles s e Educating Through Music v i a t c From an “Initiation into Classical Music” for Children to Confucian n i “Self-Cultivation” for University Students e h p s c JI ZHE r e p Confucian discourse in contemporary China simultaneously permeates the intertwined fields of politics and education. The current Confucian revival associates the “sacred”, power and knowledge whereas modernity is characterized by a differentiation between institutions and values. The paradoxical situation of Confucianism in modern society constitutes the background of the present article that explores the case of a private company involved in promoting classical Chinese music to children and “self-cultivation” to students. Its original conception of “education through music” paves the way for a new “ethical and aesthetic” teaching method that leaves aside the traditional associations of ethics with politics. By the same token, it opens the possibility for a non-political Confucianism to provide a relevant contribution in the field of education today. -

FINAL-The Farthest PBS Credits 05-08-17 V2 Formatted For

The Farthest: Voyager in Space Written & Directed by Emer Reynolds Produced by John Murray & Clare Stronge Director of Photography Kate Mc Cullough Editor Tony Cranstoun A.C.E. Executive Producers John Rubin, Keith Potter Sean B Carroll, Dennis Liu Narrator John Benjamin Hickey Line Producer Zlata Filipovic Composer Ray Harman Researcher Clare Stronge Archive Researcher / Assistant Editor Aoife Carey Production Designer Joe Fallover Sound Recordist Kieran Horgan Sound Designer Steve Fanagan CGI Visual Effects Ian Benjamin Kenny Visual Effects Enda O’Connor Production Manager – Crossing the Line Siobhán Ward Post Production Manager Séamus Connolly Camera Assistants Joseph Ingersoll James Marnell Meg O’Kelly Focus Puller Paul Shanahan Gaffers Addo Gallagher Mark Lawless Robin Olsson Grip John Foster Ronin Operator Dan Coplan S.O.C. Propman Ciarán Fogarty Props Buyer Deborah Davis Art Department Trainee Sam Fallover Art Department Transport Brian Thompson Imaging Support Eolan Power Production Assistants Brian O’ Leary Conor O’ Donovan Location Research Andrea Lewis Hannah Masterson Production Accounts Siobhán Murray Additional Assistant Editing Martin Fanning Tom Pierce Robert O’Connor Colorist Gary Curran Online Editor Eugene McCrystal Executive Producer BBC Kate Townsend Commissioning Editor ZDF/arte Sabine Bubeck-Paaz FOR HHMI TANGLED BANK STUDIOS Managing Director Anne Tarrant Director of Operations Lori Beane Director of Production Heather Forbes Director of Communications Anna Irwin Art Director Fabian de Kok-Mercado Consulting Producers