QIN MUSIC in CONTEMPORARY CHINA by Da

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voyager's Gold Record

Voyager's Gold Record https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voyager_Golden_Record #14 score, next page. YouTube (Perlman): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aVzIfSsskM0 Each Voyager space probe carries a gold-plated audio-visual disc in the event that the spacecraft is ever found by intelligent life forms from other planetary systems.[83] The disc carries photos of the Earth and its lifeforms, a range of scientific information, spoken greetings from people such as the Secretary- General of the United Nations and the President of the United States and a medley, "Sounds of Earth," that includes the sounds of whales, a baby crying, waves breaking on a shore, and a collection of music, including works by Mozart, Blind Willie Johnson, Chuck Berry, and Valya Balkanska. Other Eastern and Western classics are included, as well as various performances of indigenous music from around the world. The record also contains greetings in 55 different languages.[84] Track listing The track listing is as it appears on the 2017 reissue by ozmarecords. No. Title Length "Greeting from Kurt Waldheim, Secretary-General of the United Nations" (by Various 1. 0:44 Artists) 2. "Greetings in 55 Languages" (by Various Artists) 3:46 3. "United Nations Greetings/Whale Songs" (by Various Artists) 4:04 4. "The Sounds of Earth" (by Various Artists) 12:19 "Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F Major, BWV 1047: I. Allegro (Johann Sebastian 5. 4:44 Bach)" (by Munich Bach Orchestra/Karl Richter) "Ketawang: Puspåwårnå (Kinds of Flowers)" (by Pura Paku Alaman Palace 6. 4:47 Orchestra/K.R.T. Wasitodipuro) 7. -

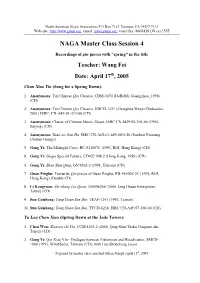

A List of Qin Recordings with a Spring Theme

North American Guqin Association, P O Box 7113, Fremont, CA 94537-7113 Web site: http://www.guqin.org, email: [email protected], voice/fax: 8668419139 ext 1555 NAGA Master Class Session 4 Recordings of qin pieces with “spring” in the title Teacher: Wang Fei Date: April 17th, 2005 Chun Xiao Yin (Song for a Spring Dawn): 1. Anonymous: Ten Chinese Qin Classics, CDM-1074 (DoReMi, Guangzhou, 1998) (CD) 2. Anonymous: Ten Chinese Qin Classics, HDCD-1121 (Zhonghua Wenyi Chubanshe, 2001) ISRC: CN-A49-01-313-00 (CD) 3. Anonymous: Classic of Chinese Music: Guqin, ISRC CN-M29-94-306-00 (1994, Beijing) (CD) 4. Anonymous: Xiao’ao Jian Hu, ISRC CN-A65-01-649-00/A.J6 (Jiuzhou Yinxiang Chuban Gongsi) 5. Gong Yi: The Midnight Crow, RC-931007C (1993, ROI, Hong Kong) (CD) 8. Gong Yi: Guqin Special Feature, CD422 998-2 (Hong Kong, 1989) (CD) 6. Gong Yi: Shan Shui Qing, GN 9202-2 (1991, Taiwan) (CD) 7. Guan Pinghu: Favourite Qin pieces of Guan Pinghu, RB-951005-2C (1995, ROI, Hong Kong) (Double CD) 8. Li Kongyuan: Shi-shang Liu Quan, 200098268 (2000, Ling Hsuan Enterprises, Taibei) (CD) 9. Sun Guisheng: Yang Guan San Die, JRAF-1241 (1992, Taiwan) 10. Sun Guisheng: Yang Guan San Die, TYCD-0238, ISRC CN-A49-97-360-00 (CD) Yu Lou Chun Xiao (Spring Dawn at the Jade Tower): 1. Chen Wen: Xianwai zhi Yin, CCM 8103-2 (2000, Qing Shan Yishu Gongzuo-shi, Taipei) (CD) 2. Gong Yi: Qin Xiao Yin - Dialogue between Fisherman and Wood-cutter, SMCD- 1008 (1995, Wind/Solar, Taiwan) (CD); with Luo Shoucheng (xiao) Prepared by master class assistant Julian Joseph April 15th, 2005 North American Guqin Association, P O Box 7113, Fremont, CA 94537-7113 Web site: http://www.guqin.org, email: [email protected], voice/fax: 8668419139 ext 1555 3. -

Westernisation, Ideology and National Identity in 20Th-Century Chinese Music

Westernisation, Ideology and National Identity in 20th-Century Chinese Music Yiwen Ouyang PhD Thesis Royal Holloway, University of London DECLARATION OF AUTHORSHIP I, Yiwen Ouyang, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 19 May 2012 I To my newly born baby II ABSTRACT The twentieth century saw the spread of Western art music across the world as Western ideology and values acquired increasing dominance in the global order. How did this process occur in China, what complexities does it display and what are its distinctive features? This thesis aims to provide a detailed and coherent understanding of the Westernisation of Chinese music in the 20th century, focusing on the ever-changing relationship between music and social ideology and the rise and evolution of national identity as expressed in music. This thesis views these issues through three crucial stages: the early period of the 20th century which witnessed the transition of Chinese society from an empire to a republic and included China’s early modernisation; the era from the 1930s to 1940s comprising the Japanese intrusion and the rising of the Communist power; and the decades of economic and social reform from 1978 onwards. The thesis intertwines the concrete analysis of particular pieces of music with social context and demonstrates previously overlooked relationships between these stages. It also seeks to illustrate in the context of the appropriation of Western art music how certain concepts acquired new meanings in their translation from the European to the Chinese context, for example modernity, Marxism, colonialism, nationalism, tradition, liberalism, and so on. -

An Explanation of Gexing

Front. Lit. Stud. China 2010, 4(3): 442–461 DOI 10.1007/s11702-010-0107-5 RESEARCH ARTICLE XUE Tianwei, WANG Quan An Explanation of Gexing © Higher Education Press and Springer-Verlag 2010 Abstract Gexing 歌行 is a historical and robust prosodic style that flourished (not originated) in the Tang dynasty. Since ancient times, the understanding of the prosody of gexing has remained in debate, which focuses on the relationship between gexing and yuefu 乐府 (collection of ballad songs of the music bureau). The points-of-view held by all sides can be summarized as a “grand gexing” perspective (defining gexing in a broad sense) and four major “small gexing” perspectives (defining gexing in a narrow sense). The former is namely what Hu Yinglin 胡应麟 from Ming dynasty said, “gexing is a general term for seven-character ancient poems.” The first “small gexing” perspective distinguishes gexing from guti yuefu 古体乐府 (tradition yuefu); the second distinguishes it from xinti yuefu 新体乐府 (new yuefu poems with non-conventional themes); the third takes “the lyric title” as the requisite condition of gexing; and the fourth perspective adopts the criterion of “metricality” in distinguishing gexing from ancient poems. The “grand gexing” perspective is the only one that is able to reveal the core prosodic features of gexing and give specification to the intension and extension of gexing as a prosodic style. Keywords gexing, prosody, grand gexing, seven-character ancient poems Received January 25, 2010 XUE Tianwei ( ) College of Humanities, Xinjiang Normal University, Urumuqi 830054, China E-mail: [email protected] WANG Quan International School, University of International Business and Economics, Beijing 100029, China E-mail: [email protected] An Explanation of Gexing 443 The “Grand Gexing” Perspective and “Small Gexing” Perspective Gexing, namely the seven-character (both unified seven-character lines and mixed lines containing seven character ones) gexing, occupies an equal position with rhythm poems in Tang dynasty and even after that in the poetic world. -

Expanding Our Horizons

合中 作 澳拓展视野 与 教 育交 科 流 研 四 十 年 EXPANDING OUR HORIZONS Forty years of Australia-China collaboration and exchange in education, science and research Published by the Department of Industry, Innovation, Science, Research and Tertiary Education Project Director: Cathryn Hlavka Research, writing and editing: China Policy, Asia Pacific Access Translation: EZer Translation Company, Beijing Designed and produced by Printed by BEIJING ARTRON COLOUR PRINTING CO. LTD. Contents 目录 The DVD enclosed, Learning Never Ends, was produced in November 2012 as part of this project Research: China Policy, Asia Pacific Access Film production: Mandarin Film (Beijing) How it all began 8 源起 ISBN: 978-1-922218-69-8 © Commonwealth of Australia 2013 走上征程 This book is not for sale First steps on the way 26 上学去 This work is copyright. Apart from use as permitted under the Copyright Off to school 44 Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth. Requests and inquiries concerning On to college 62 上大学 reproduction ad rights should be addressed to the Commonwealth Copyright Administration. Attorney-General's Department, Robert Garran Offices, National Building for the future 88 建设未来 Circuit, Barton ACT 2600 or posed at http://www.ag.gov.au/cca Collaboration in science 102 科学合作 Expanding horizons 122 拓展视野 Contributors 138 贡献者 Disclaimer This book was commissioned by the Department of Industry, Innovation, Sources for official documents 139 政府资料参考 Science, Research and Tertiary Education. The contents remain the responsibility of the writing team and the many individuals who contributed Index 140 索引 their personal stories. -

Download (3MB)

Lipsey, Eleanor Laura (2018) Music motifs in Six Dynasties texts. PhD thesis. SOAS University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/32199 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Music motifs in Six Dynasties texts Eleanor Laura Lipsey Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD 2018 Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures China & Inner Asia Section SOAS, University of London 1 Abstract This is a study of the music culture of the Six Dynasties era (220–589 CE), as represented in certain texts of the period, to uncover clues to the music culture that can be found in textual references to music. This study diverges from most scholarship on Six Dynasties music culture in four major ways. The first concerns the type of text examined: since the standard histories have been extensively researched, I work with other types of literature. The second is the casual and indirect nature of the references to music that I analyze: particularly when the focus of research is on ideas, most scholarship is directed at formal essays that explicitly address questions about the nature of music. -

Recent Publications in Music 2009

Fontes Artis Musicae, Vol. 56/4 (2009) RECENT PUBLICATIONS IN MUSIC R1 RECENT PUBLICATIONS IN MUSIC 2009 On behalf of the International Association of Music Libraries Archives and Documentation Centres / Pour le compte l'Association Internationale des Bibliothèques, Archives et Centres de Documentation Musicaux / Im Auftrag der Die Internationale Vereinigung der Musikbibliotheken, Musikarchive und Musikdokumentationszentren This list contains citations to literature about music in print and other media, emphasizing reference materials and works of research interest that appeared in 2008. Reporters who contribute regularly provide citations mainly or only from the year preceding the year this list is published in the IAML journal Fontes Artis Musicae. However, reporters may also submit retrospective lists cumulating publications from up to the previous five years. In the hope that geographic coverage of this list can be expanded, the compiler welcomes inquiries from bibliographers in countries not presently represented. Compiled and edited by Geraldine E. Ostrove Reporters: Austria: Thomas Leibnitz Canada: Marlene Wehrle China, Hong Kong, Taiwan: Katie Lai Croatia: Zdravko Blaţeković Czech Republic: Pavel Kordík Estonia: Katre Rissalu Finland: Ulla Ikaheimo, Tuomas Tyyri France: Cécile Reynaud Germany: Wolfgang Ritschel Ghana: Santie De Jongh Greece: Alexandros Charkiolakis Hungary: Szepesi Zsuzsanna Iceland: Bryndis Vilbergsdóttir Ireland: Roy Stanley Italy: Federica Biancheri Japan: Sekine Toshiko Namibia: Santie De Jongh The Netherlands: Joost van Gemert New Zealand: Marilyn Portman Russia: Lyudmila Dedyukina South Africa: Santie De Jongh Spain: José Ignacio Cano, Maria José González Ribot Sweden Turkey: Paul Alister Whitehead, Senem Acar United States: Karen Little, Liza Vick. With thanks for assistance with translations and transcriptions to Kersti Blumenthal, D. -

An Ideological Analysis of the Birth of Chinese Indie Music

REPHRASING MAINSTREAM AND ALTERNATIVES: AN IDEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF THE BIRTH OF CHINESE INDIE MUSIC Menghan Liu A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2012 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Kristen Rudisill Esther Clinton © 2012 MENGHAN LIU All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor This thesis project focuses on the birth and dissemination of Chinese indie music. Who produces indie? What is the ideology behind it? How can they realize their idealistic goals? Who participates in the indie community? What are the relationships among mainstream popular music, rock music and indie music? In this thesis, I study the production, circulation, and reception of Chinese indie music, with special attention paid to class, aesthetics, and the influence of the internet and globalization. Borrowing Stuart Hall’s theory of encoding/decoding, I propose that Chinese indie music production encodes ideologies into music. Pierre Bourdieu has noted that an individual’s preference, namely, tastes, corresponds to the individual’s profession, his/her highest educational degree, and his/her father’s profession. Whether indie audiences are able to decode the ideology correctly and how they decode it can be analyzed through Bourdieu’s taste and distinction theory, especially because Chinese indie music fans tend to come from a community of very distinctive, 20-to-30-year-old petite-bourgeois city dwellers. Overall, the thesis aims to illustrate how indie exists in between the incompatible poles of mainstream Chinese popular music and Chinese rock music, rephrasing mainstream and alternatives by mixing them in itself. -

Legal Aspects of the Commodity and Financial Futures Market in China Sanzhu Zhu

Brooklyn Journal of Corporate, Financial & Commercial Law Volume 3 | Issue 2 Article 4 2009 Legal Aspects of the Commodity and Financial Futures Market in China Sanzhu Zhu Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjcfcl Recommended Citation Sanzhu Zhu, Legal Aspects of the Commodity and Financial Futures Market in China, 3 Brook. J. Corp. Fin. & Com. L. (2009). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjcfcl/vol3/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Journal of Corporate, Financial & Commercial Law by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. LEGAL ASPECTS OF THE COMMODITY AND FINANCIAL FUTURES MARKET IN CHINA Sanzhu Zhu* I. INTRODUCTION The establishment of China’s first commodity futures exchange in Zhengzhou, Henan in October 1990 marked the emergence of a futures market in China. The Zhengzhou Commodity Exchange was created in the wake of the country’s economic reform and development, and it became the first experimental commodity futures market approved by the central government. The Zhengzhou Commodity Exchange provided a platform and facilitated a need for commodity futures trading arising alongside China’s economic reform, which had begun in 1978, and which was moving towards a market economy by the early 1990s.1 Sixteen years later, the China Financial Futures Exchange (CFFEX) was established in Shanghai.2 This was followed by the opening of gold futures trading on the Shanghai Futures Exchange on January 9, 2008.3 China gradually developed a legal and regulatory framework for its commodity and financial futures markets beginning in the early 1990s, * Senior Lecturer in Chinese commercial law, School of Law, SOAS, University of London. -

Downloaded At

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Professionalizing Service Provision : The Field of Social Work in Urban China Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/388729pv Author Han, Ling Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Professionalizing Service Provision: The Field of Social Work in Urban China A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology by Ling Han Committee in charge: Professor Richard Madsen, Chair Professor Richard Biernacki Professor Kwai Ng Professor Paul Pickowicz Professor Nancy Postero Professor Christena Turner 2015 Copyright Ling Han, 2015 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Ling Han is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2015 iii DEDICATION For my parents iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page .................................................................................................................. -

Music-Based TV Talent Shows in China: Celebrity and Meritocracy in the Post-Reform Society

Music-Based TV Talent Shows in China: Celebrity and Meritocracy in the Post-Reform Society by Wei Huang B. A., Huaqiao University, 2013 Extended Essays Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Communication (Dual Degree in Global Communication) Faculty of Communication, Art & Technology © Wei Huang 2015 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2015 Approval Name: Wei Huang Degree: Master of Arts (Communication) Title: Music-Based TV Talent Shows in China: Celebrity and Meritocracy in the Post-Reform Society Examining Committee: Program Director: Yuezhi Zhao Professor Frederik Lesage Senior Supervisor Assistant Professor School of Communication Simon Fraser University Baohua Wang Supervisor Professor School of Communication Communication University of China Date Defended/Approved: August 31, 2015 ii Abstract Meritocracy refers to the idea that whatever our social position at birth, society should offer the means for those with the right “talent” to “rise to top.” In context of celebrity culture, it could refer to the idea that society should allow all of us to have an equal chance to become celebrities. This article argues that as a result of globalization and consumerism in the post-reform market economy, the genre of music-based TV talent shows has become one of the most popular TV genres in China and has at the same time become a vehicle of a neoliberal meritocratic ideology. The rise of the ideology of meritocracy accompanied the pace of market reform in post-1980s China and is influenced by the loss of social safety nets during China’s transition from a socialist to a market economy. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles the Qin

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Qin and Literati Culture in Song China A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures by Meimei Zhang 2019 © Copyright by Meimei Zhang 2019 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Qin and Literati Culture in Song China by Meimei Zhang Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures University of California, Los Angeles, 2019 Professor David C Schaberg, Chair My dissertation examines the distinctive role that the qin played in Chinese literati culture in the Song dynasty (960-1279) through its representations in literary texts. As one of the earliest stringed musical instruments in China, the qin has occupied a unique status in Chinese cultural history. It has been played since ancient times, and has traditionally been favored by Chinese scholars and literati as an instrument of great subtlety and refinement. This dissertation focuses on the period of the Song because it was during this period that the literati developed as a class and started to indulge themselves in various cultural and artistic pursuits, and record their experiences in literary compositions as part of their self-fashioning. Among these cultural pursuits, the qin playing was an important one. Although there have been several academic works on the qin, most of them focus on the musical aspects of the instrument. My project aims to reorient the perspective on the qin by revealing its close relationship and interaction with the literati class from a series of ii historical and literary approaches. During the Song, the qin was mentioned in a multiplicity of literary texts, and associated with a plethora of renowned literary figures.