Migrant Thoughts Cinematographic Intersections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Gioco' E Del 'Montaggio'

Magazine del Festival ricerche e progetti research and projects on FAM dell’Architettura sull’architettura e la città architecture and the city Del ‘gioco’ 51 e del ‘montaggio’ nella didattica e nella composizione Elvio Manganaro Del gioco e del montaggio Tommaso Brighenti Per gioco ma sul serio Gianluca Maestri Note sulle semantiche del gioco Francesco Zucconi Montaggio e anatopismo secondo Jean-Luc Godard Antonella Sbrilli Sette appunti su scatole di giochi, artisti e storie dell’arte Laura Scala La Vittoria sul Sole di Malevič: la dissoluzione della realtà Cosimo Monteleone Frank Lloyd Wright e il gioco dell’astrazione geometrica Amra Salihbegovic Apologia per un’architettura del gioco Elvio Manganaro “Montage, mon beau souci” Tamar Zinguer All’origine della Sandbox Enrico Bordogna Il ragazzo dello IUAV Giuseppe Tupputi Le architetture metropolitane di Paulo Mendes da Rocha.Tra concezione spaziale e ideazione strutturale Giuseppe Verterame Abitare lo spazio attraverso archetipi. Letture delle opere di Kahn e Mies DOI: 10.1283/fam/issn2039-0491/n51-2020 Magazine del Festival ricerche e progetti research and projects on FAM dell’Architettura sull’architettura e la città architecture and the city FAMagazine. Ricerche e progetti sull’architettura e la città Editore: Festival Architettura Edizioni, Parma, Italia ISSN: 2039-0491 Segreteria di redazione c/o Università di Parma Campus Scienze e Tecnologie Via G. P. Usberti, 181/a 43124 - Parma (Italia) Email: [email protected] www.famagazine.it Editorial Team Direzione Enrico Prandi, -

Program Book Final 1-16-15.Pdf

4 5 7 BUFFALO PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA TABLE OF CONTENTS | JANUARY 24 – FEBRUARY 15, 2015 BPO Board of Trustees/BPO Foundation Board of Directors 11 BPO Musician Roster 15 Happy Birthday Mozart! 17 M&T Bank Classics Series January 24 & 25 Alan Parsons Live Project 25 BPO Rocks January 30 Ben Vereen 27 BPO Pops January 31 Russian Diversion 29 M&T Bank Classics Series February 7 & 8 Steve Lippia and Sinatra 35 BPO Pops February 13 & 14 A Very Beary Valentine 39 BPO Kids February 15 Corporate Sponsorships 41 Spotlight on Sponsor 42 Meet a Musician 44 Annual Fund 47 Patron Information 57 CONTACT VoIP phone service powered by BPO Administrative Offices (716) 885-0331 Development Office (716) 885-0331 Ext. 420 BPO Administrative Fax Line (716) 885-9372 Subscription Sales Office (716) 885-9371 Box Office (716) 885-5000 Group Sales Office (716) 885-5001 Box Office Fax Line (716) 885-5064 Kleinhans Music Hall (716) 883-3560 Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra | 499 Franklin Street, Buffalo, NY 14202 www.bpo.org | [email protected] Kleinhan's Music Hall | 3 Symphony Circle, Buffalo, NY 14201 www.kleinhansbuffalo.org 9 MESSAGE FROM BOARD CHAIR Dear Patrons, Last month witnessed an especially proud moment for the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra: the release of its “Built For Buffalo” CD. For several years, we’ve presented pieces commissioned by the best modern composers for our talented musicians, continuing the BPO’s tradition of contributing to classical music’s future. In 1946, the BPO made the premiere recording of the Shostakovich Leningrad Symphony. Music director Lukas Foss was also a renowned composer who regularly programmed world premieres of the works of himself and his contemporaries. -

Phonographic Performance Company of Australia Limited Control of Music on Hold and Public Performance Rights Schedule 2

PHONOGRAPHIC PERFORMANCE COMPANY OF AUSTRALIA LIMITED CONTROL OF MUSIC ON HOLD AND PUBLIC PERFORMANCE RIGHTS SCHEDULE 2 001 (SoundExchange) (SME US Latin) Make Money Records (The 10049735 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) 100% (BMG Rights Management (Australia) Orchard) 10049735 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) Music VIP Entertainment Inc. Pty Ltd) 10065544 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) 441 (SoundExchange) 2. (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) NRE Inc. (The Orchard) 100m Records (PPL) 777 (PPL) (SME US Latin) Ozner Entertainment Inc (The 100M Records (PPL) 786 (PPL) Orchard) 100mg Music (PPL) 1991 (Defensive Music Ltd) (SME US Latin) Regio Mex Music LLC (The 101 Production Music (101 Music Pty Ltd) 1991 (Lime Blue Music Limited) Orchard) 101 Records (PPL) !Handzup! Network (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) RVMK Records LLC (The Orchard) 104 Records (PPL) !K7 Records (!K7 Music GmbH) (SME US Latin) Up To Date Entertainment (The 10410Records (PPL) !K7 Records (PPL) Orchard) 106 Records (PPL) "12"" Monkeys" (Rights' Up SPRL) (SME US Latin) Vicktory Music Group (The 107 Records (PPL) $Profit Dolla$ Records,LLC. (PPL) Orchard) (SME US Latin) VP Records - New Masters 107 Records (SoundExchange) $treet Monopoly (SoundExchange) (The Orchard) 108 Pics llc. (SoundExchange) (Angel) 2 Publishing Company LCC (SME US Latin) VP Records Corp. (The 1080 Collective (1080 Collective) (SoundExchange) Orchard) (APC) (Apparel Music Classics) (PPL) (SZR) Music (The Orchard) 10am Records (PPL) (APD) (Apparel Music Digital) (PPL) (SZR) Music (PPL) 10Birds (SoundExchange) (APF) (Apparel Music Flash) (PPL) (The) Vinyl Stone (SoundExchange) 10E Records (PPL) (APL) (Apparel Music Ltd) (PPL) **** artistes (PPL) 10Man Productions (PPL) (ASCI) (SoundExchange) *Cutz (SoundExchange) 10T Records (SoundExchange) (Essential) Blay Vision (The Orchard) .DotBleep (SoundExchange) 10th Legion Records (The Orchard) (EV3) Evolution 3 Ent. -

Sigmund Freud Papers

Sigmund Freud Papers A Finding Aid to the Papers in the Sigmund Freud Collection in the Library of Congress Digitization made possible by The Polonsky Foundation Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2015 Revised 2016 December Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms004017 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm80039990 Prepared by Allan Teichroew and Fred Bauman with the assistance of Patrick Holyfield and Brian McGuire Revised and expanded by Margaret McAleer, Tracey Barton, Thomas Bigley, Kimberly Owens, and Tammi Taylor Collection Summary Title: Sigmund Freud Papers Span Dates: circa 6th century B.C.E.-1998 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1871-1939) ID No.: MSS39990 Creator: Freud, Sigmund, 1856-1939 Extent: 48,600 items ; 141 containers plus 20 oversize and 3 artifacts ; 70.4 linear feet ; 23 microfilm reels Language: Collection material in German, with English and French Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Founder of psychoanalysis. Correspondence, holograph and typewritten drafts of writings by Freud and others, family papers, patient case files, legal documents, estate records, receipts, military and school records, certificates, notebooks, a pocket watch, a Greek statue, an oil portrait painting, genealogical data, interviews, research files, exhibit material, bibliographies, lists, photographs and drawings, newspaper and magazine clippings, and other printed matter. The collection documents many facets of Freud's life and writings; his associations with family, friends, mentors, colleagues, students, and patients; and the evolution of psychoanalytic theory and technique. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. -

Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND SUBJECT INDEX Film review titles are also Akbari, Mania 6:18 Anchors Away 12:44, 46 Korean Film Archive, Seoul 3:8 archives of television material Spielberg’s campaign for four- included and are indicated by Akerman, Chantal 11:47, 92(b) Ancient Law, The 1/2:44, 45; 6:32 Stanley Kubrick 12:32 collected by 11:19 week theatrical release 5:5 (r) after the reference; Akhavan, Desiree 3:95; 6:15 Andersen, Thom 4:81 Library and Archives Richard Billingham 4:44 BAFTA 4:11, to Sue (b) after reference indicates Akin, Fatih 4:19 Anderson, Gillian 12:17 Canada, Ottawa 4:80 Jef Cornelis’s Bruce-Smith 3:5 a book review; Akin, Levan 7:29 Anderson, Laurie 4:13 Library of Congress, Washington documentaries 8:12-3 Awful Truth, The (1937) 9:42, 46 Akingbade, Ayo 8:31 Anderson, Lindsay 9:6 1/2:14; 4:80; 6:81 Josephine Deckers’s Madeline’s Axiom 7:11 A Akinnuoye-Agbaje, Adewale 8:42 Anderson, Paul Thomas Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Madeline 6:8-9, 66(r) Ayeh, Jaygann 8:22 Abbas, Hiam 1/2:47; 12:35 Akinola, Segun 10:44 1/2:24, 38; 4:25; 11:31, 34 New York 1/2:45; 6:81 Flaherty Seminar 2019, Ayer, David 10:31 Abbasi, Ali Akrami, Jamsheed 11:83 Anderson, Wes 1/2:24, 36; 5:7; 11:6 National Library of Scotland Hamilton 10:14-5 Ayoade, Richard -

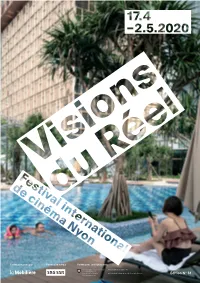

Vdr Prog 2020.Pdf

1 Partenaire principal Partenaire média Partenaires institutionnels Édition N° 51 2 1 Croquis du sinistre Editorial Fr Une édition qui non seulement doit En An edition that must not only forgo renoncer à son apparence physique, mais its physical form, but also exist in a world which, aussi exister dans un monde qui, tel un film de like a grade-Z science-fiction film, seems to be science-fiction de série Z, semble sur le point on the verge of disappearing in its known form… de disparaître dans sa forme connue… On 16 March, the entire Visions du Réel team Le 16 mars, toute l’équipe a amorcé la préparation began the preparation of a profoundly re-invented d’un Festival profondément ré-inventé, à distance, edition, working remotely, making great use à grand renfort de Skypes, de Zoom et de Google of Skype, Zoom and Google Docs, with frustration, Docs, s’énervant, s’enthousiasmant, sans réponses with enthusiasm, and sometimes without answers face à tant d’incertitudes. C’est là que se révèle, in the face of so much incertitude. It is here, in the au cœur de la crise, la beauté du collectif et les heart of the crisis, that the beauty of the collective énergies qui se complètent lorsque certain.e.s is revealed, the energies that complement each faiblissent. other when some weaken. Alors certes, VdR 2020 n’a pas lieu à la Place du So, of course, Visions du Réel 2020 is not taking Réel, dans les salles de cinéma, ou sous la tente. place at the Place du Réel, in the cinemas, or Mais il se tient résolument sur internet, dans in the tent. -

Your LIFF 2018 Guide

Welcome Welcome to your LIFF 2018 Guide. The global programme of the 32nd Leeds International Film Festival is all yours for exploring! You can find over 350 feature films, documentaries and shorts from 60 countries across five major programme sections: Official Selection, Cinema Versa, Fanomenon, Time Frames and Leeds Short Film Awards. You have over 300 eye-opening screenings and events to choose from at many of the city’s favourite venues and whether you want to see 6 or 60, we have great value passes and ticket offers available. We hope you have a wonderful experience at LIFF 2018 with 1000s of other film explorers! Contents LIFF 2018 Catalogue In the LIFF 2018 Catalogue you can Tickets / Map 4 discover more information about every Schedule 6 film presented in the programme. The Partners 11 catalogue will be available for FREE from Leeds Town Hall from 1 November, but Official Selection 14 there will be a limited supply so pick up Cinema Versa 34 your copy early!! Fanomenon 52 LIFF 2018 Online Time Frames 70 Leeds Short You can find the full LIFF 2018 programme online at leedsfilmcity.com where you 0113 376 0318 Film Awards 90 can also access the latest news including BOX OFFICE Index 100 guest announcements and award winners. To receive LIFF 2018 news first, join us on social media @leedsfilmfest and with # L I FF2018. Leeds International Screendance Competition Screendance Leeds International 3 Leeds Town Hall City Varieties Venues The Headrow, Leeds LS1 3AD Swan St, Leeds LS1 6LW Hyde Park Picture House Belgrave Music Hall 73 Brudenell -

Sfreeweekl Ysince | De Cember

CHICAGO’SFREEWEEKLYSINCE | DECEMBER | DECEMBER CHICAGO’SFREEWEEKLYSINCE Year in review THIS WEEK CHICAGOREADER | DECEMBER | VOLUME NUMBER IN THIS ISSUE T R - CITYLIFE 16 FeatureTheworsteverday 27 Galil|ListenTheshrinking 03 TransportationLightfoot’s inChicagotheaterprovides ofmusicmediarequiresanew @ doneagoodjobofkeepingher theimpetusforabeloved defi nitionof“overlooked” promisetopromotemobility quirkyholidayshow buteventhestrictestcriteria PTB ADVERTISING EC -- - @ STAFFING CHANGES justicewithoneglaring 17 Review TheLightinthe admitavastunexploredtrove S K KH AT THE READER exception PiazzashinesatLyric ofriches CL C @ 18 ShowsThebestofChicago 28 ShowsofnoteAvreeaylRa S K MEP M KEEN EYED READERS of NEWS& theaterinputthe andTimeMachineAntiFlag TD SDP F spotlightonreshapingold TamaSumo&Lakutiandmore KR VPS our masthead will notice POLITICS narrativesandfalsehistory thisweek CEBW A M several changes we’d like AEJL CR M 04 Joravsky|PoliticsAsthe 19 DanceThebestmomentsin 31 TheSecretHistoryof SWDI T P to acknowledge this week. teensturntothetwentiesit’s dancethisyearfocusedonthe ChicagoMusicHard BJMS SAR After 20 years with the astruggletofi ndcheerinthe powerofcommunity workingcountryrockersthe SWM L M-H DLG L S Reader, Kate Schmidt is gloom 20 PlaysofNote America’s Moondogsneverreleasedtheir EA CSM stepping away from her role 07 Dukmasova|NewsAnight BestOutcastToyisheartfelt onlyalbum S N L W R as deputy editor to pursue spentrevelingintheabsurdity andfunnyTheMysteryof 32 EarlyWarningsSteveAoki -

PPCA Licensors Phonographic Performance Company of Australia Limited Control of Music on Hold and Public Performance Rights

PPCA Licensors Phonographic Performance Company of Australia Limited Control of Music on Hold and Public Performance Rights 88dB Bowles Production *ABC Music Brian Lord Entertainment ACMEC Bridge, Billy Adams, Clelia Broad Music AGR Television Records Buckley, Russell Aitken, Gregory A. Budimir, Mary Michelle AITP Records Bullbar P/L aJaymusic Bulletproof Records t/a Fighterpilot AJO Services Bulmer, Grant Matthew Allan, Jane Bunza Entertainment International Pty Ltd Aloha Management Pty Ltd Butler Brown P/L t/a The John Butler Trio Alter Ego Promotions Byrne, Craig Alston, Chris Byrne, Janine Alston, Mark *CAAMA Music Amber Records Aust. Pty Ltd. Cameron Bracken Concepts Amphibian *Care Factor Zero Recordz Anamoe Productions Celtic Records Anderson, James Gordon SA 5006 Angelik Central Station Pty Ltd Angell, Matt Charlie Chan Music Pty Ltd Anthem Pty Ltd Chart Records and Publishing Anvil Records Chase Corporation P/L Anvil Lane Records Chatterbox Records P/L Appleseed Cheshire, Kim Armchair Circus Music Chester, John Armchair Productions t/a Artworks Recorded Circle Records Music CJJM Australian Music Promotions Artistocrat P/L Clarke, Denise Pamela Arvidson, Daniel Clifton, Jane Ascension World Music Productions House Coggan, Darren Attar, Lior Col Millington Prodcutions *Australian Music Centre Collins, Andrew James B.E. Cooper Pty Ltd *Colossal Records of Australia Pty Ltd B(if)tek Conlaw (No. 16) Pty Ltd t/a Sundown Records Backtrack Music Coo-ee Music Band Camp Cooper, Jacki Bellbird Music Pty Ltd Coulson, Greg Below Par Records -

Archivio Cd Stranieri.Xlsx

50 CENT 2003 - GET RICH ON DIE A HA 1985 - HUNTING HIGH AND LOW A HA 2005 - ANALOGUE A HA 2005 - THE DEFINITIVE SINGLES COLLECTION 1984-2004 A HA 2009 - FOOT OF THE MOUNTAIN A HA 2011 - ENDING ON A HIGH NOTE LIVE AT OSLO SPEKTRUM 2CD A HA 2015 - CAST IN STEEL A HA 2016 - TIME AND AGAIN THE ULTIMATE 2CD A HA 2017 - UNPLUGGED SUMMER SOLSTICE 2CD ABBA 1992 - GOLG GREATEST HITS ABBA 2008 - MORE ABBA GOLD MORE ABBA HITS ABBA 2011 - COLLECTED 3CD ABBA 2012 - THE VISITORS ABBA 2014 - LIVE AT WEMBLEY ARENA 1979 2CD AC DC 2008 - BLACK ICE ADELE 2008 - 19 ADELE 2011 - 21 ADELE 2011 - LIVE AT THE ROYAL ALBERT HALL LIVE ADELE 2012 - GREATEST HITS ADELE 2015 - 25 AEROSMITH 2012 - MUSIC FROM ANOTHER DIMENSION AIR 2007 - POCKET SYMPHONY AKHENATON SOLDATS DE FORTUNE AL STEWART 1976 - YEAR OF THE CAT ALABAMA 2007 - 16 BIGGEST HITS ALAIN CLARK 2007 - LIVE IT OUT ALANIS MORISSETTE 2004 - SO CALLED CHAOS ALANIS MORISSETTE 2005 - THE COLLECTION ALANIS MORISSETTE 2008 - FLAVORS OF ENTANGLEMENT ALANIS MORISSETTE 2012 - HAVOC AND BRIGHT LIGHTS ALESHA DIXON 2011 - THE ENTERTAINER ALICIA KEYS 2009 - THE ELEMENT OF FREEDOM ALICIA KEYS 2012 - GIRL ON FIRE ALICIA KEYS 2016 - HERE ALICIA KYES 2003 - THE DIARY OF ALICIA KYES ALICIA KYES 2005 - MTV UNPLUGGED Live ALICIA KYES 2007 - AS I AM ALISON MOYET 2009 - THE BEST OF ALL SAINTS 1997 - ALL SAINTS ALL SAINTS 2000 - SAINTS AND SINNERS ALL SAINTS 2006 - STUDIO 1 ALL WOMAN 2003 - 41 CLASSICS FOR THE CONTEMPORARY 2CD ALL WOMAN 2003 - ALL WOMAN 4CD ALL WOMAN 2003 - THE NEW HITS COLLECTION 2CD ALL WOMAN 2006 - THE PLATIMUN -

Fifteen Lessons with Godard

SEEING FROM SCRATCH ◊ by RICHARD DIENST with 15 LESSONS WITH GODARD ◊ THE POSTCARD GAME SEEING FROM SCRATCH ◊ by RICHARD DIENST with 15 LESSONS WITH GODARD ◊ THE POSTCARD GAME SEEING FROM SCRATCH ◊ by RICHARD DIENST with 15 LESSONS WITH GODARD ◊ THE POSTCARD GAME SEEING FROM SCRATCH ◊ by RICHARD DIENST with 15 LESSONS WITH GODARD ◊ THE POSTCARD GAME SEEING FROM SCRATCH ◊ by RICHARD DIENST with 15 LESSONS WITH GODARD ◊ THE POSTCARD GAME SEEING FROM SCRATCH ◊ by RICHARD DIENST with 15 LESSONS WITH GODARD ◊ THE POSTCARD GAME SEEING FROM SCRATCH ◊ by RICHARD DIENST with 15 LESSONS WITH GODARD ◊ THE POSTCARD GAME SEEING FROM SCRATCH ◊ by RICHARD DIENST with 15 LESSONS WITH GODARD ◊ THE POSTCARD GAME SEEING FROM SCRATCH ◊ by RICHARD DIENST with 15 LESSONS WITH GODARD ◊ THE POSTCARD GAME SEEING FROM SCRATCH ◊ by RICHARD DIENST with 15 LESSONS WITH GODARD ◊ THE POSTCARD GAME SEEING FROM SCRATCH ◊ by RICHARD DIENST with 15 LESSONS WITH GODARD ◊ THE POSTCARD GAME SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH with THE POSTCARD GAME THE POSTCARD GAME CABOOSE SEEING FROM SCRATCH ◊ 15 LESSONS WITH GODARD with THE POSTCARD GAME ◊ RICHARD DIENST CABOOSE ◊ MONTREAL SEEING FROM SCRATCH 1 INTERMISSION 99 THE POSTCARD GAME 103 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 131 COLOPHON 132 SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN 3 In 1979 Jean-Luc Godard filled a page ofCahiers du Cinéma with the word LEARN (APPRENDRE).1 It appears twenty-two times. -

Historical Collections in Psychiatry and Psychoanalysis

Historical Collections in Psychiatry and Psychoanalysis MARY MYLENKI ANYDISCUSSION OF THE HISTORY of psychiatry and psychoanalysis is as broad as the scope and definition of those terms. Is psychiatry a rrla- tively new branch of medicine with psychoanalysis merely its newest branch? Did Freud invent or define it-depending upon the point of view-less than one hundred years ago? Or is it as old as man’s interest in the human mind? Since librarians are not (nor should they be) arbiters of these issues, it is not surprising that most libraries with collections devoted to the history of psychiatry take a broad view of the literature dealing with mental disorders, aberrations and peculiar behavior through the years. The literature encompasses the reactions of laymen as well as of the established medical, legal or religious powers of the time. Those holding the view that psychiatry is a “modern” field of medicine may be surprised to learn that several of the libraries discussed in this article have some incunabula in their collections. Virtually all of these early published works deal with the cause and cure of witchcraft- the cures in most cases being pretty drastic. Then there was the early psychiatric diagnosis of “melancholie,” popular in poetic literature as well as in medicine. And as everyone knows, Shakespeare was a fairly good Freudian. Later one can add to the list of psychiatric subjects hysteria, phrenology, mesmerism and hypnosis, spiritualism, and some which are still very much with us, likealcoholism anddrug abuse. All of these may be considered within the realm of psychiatry or psychoanaly- Mary Mylenki is Senior Assistant Librarian, Payne Whitney Psychiatric Clinic Library, New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center, New York.