Fifteen Lessons with Godard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Gioco' E Del 'Montaggio'

Magazine del Festival ricerche e progetti research and projects on FAM dell’Architettura sull’architettura e la città architecture and the city Del ‘gioco’ 51 e del ‘montaggio’ nella didattica e nella composizione Elvio Manganaro Del gioco e del montaggio Tommaso Brighenti Per gioco ma sul serio Gianluca Maestri Note sulle semantiche del gioco Francesco Zucconi Montaggio e anatopismo secondo Jean-Luc Godard Antonella Sbrilli Sette appunti su scatole di giochi, artisti e storie dell’arte Laura Scala La Vittoria sul Sole di Malevič: la dissoluzione della realtà Cosimo Monteleone Frank Lloyd Wright e il gioco dell’astrazione geometrica Amra Salihbegovic Apologia per un’architettura del gioco Elvio Manganaro “Montage, mon beau souci” Tamar Zinguer All’origine della Sandbox Enrico Bordogna Il ragazzo dello IUAV Giuseppe Tupputi Le architetture metropolitane di Paulo Mendes da Rocha.Tra concezione spaziale e ideazione strutturale Giuseppe Verterame Abitare lo spazio attraverso archetipi. Letture delle opere di Kahn e Mies DOI: 10.1283/fam/issn2039-0491/n51-2020 Magazine del Festival ricerche e progetti research and projects on FAM dell’Architettura sull’architettura e la città architecture and the city FAMagazine. Ricerche e progetti sull’architettura e la città Editore: Festival Architettura Edizioni, Parma, Italia ISSN: 2039-0491 Segreteria di redazione c/o Università di Parma Campus Scienze e Tecnologie Via G. P. Usberti, 181/a 43124 - Parma (Italia) Email: [email protected] www.famagazine.it Editorial Team Direzione Enrico Prandi, -

Between Objective Engagement and Engaged Cinema: Jean- Luc

It is often argued that between 1967 and 1974 Godard operated under a misguided assessment of the effervescence of the social and political situation and produced the equivalent of “terrorism” in filmmaking. He did this, as the argument goes, by both subverting the formal operations of narrative film and by being biased 01/13 toward an ideological political engagement.1 Here, I explore the idea that Godard’s films of this period are more than partisan political statements or anti-narrative formal experimentations. The filmmaker’s response to the intense political climate that reigned during what he would retrospectively call his “leftist trip” years was based on a filmic-theoretical Irmgard Emmelhainz praxis in a Marxist-Leninist vein. Through this I t praxis, Godard explored the role of art and artists r a and their relationship to empirical reality. He P , Between ) 4 examined these in three arenas: politics, 7 9 aesthetics, and semiotics. His work between 1 - Objective 7 1967 and 1974 includes the production of 6 9 1 collective work with the Dziga Vertov Group (DVG) ( ” g until its dissolution in 1972, and culminates in Engagement n i k his collaboration with Anne-Marie Miéville under a m the framework of Sonimage, a new production m l and Engaged i company founded in 1973 as a project of F t n “journalism of the audiovisual.” a t i l ÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊGodard’s leftist trip period can be bracketed Cinema: Jean- i M by two references he made to other politically “ s ’ engaged artists. In Camera Eye, his contribution d Luc Godard’s r a to the collectively-made film Loin du Vietnam of d o G 1967, Godard refers to André Breton. -

Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND SUBJECT INDEX Film review titles are also Akbari, Mania 6:18 Anchors Away 12:44, 46 Korean Film Archive, Seoul 3:8 archives of television material Spielberg’s campaign for four- included and are indicated by Akerman, Chantal 11:47, 92(b) Ancient Law, The 1/2:44, 45; 6:32 Stanley Kubrick 12:32 collected by 11:19 week theatrical release 5:5 (r) after the reference; Akhavan, Desiree 3:95; 6:15 Andersen, Thom 4:81 Library and Archives Richard Billingham 4:44 BAFTA 4:11, to Sue (b) after reference indicates Akin, Fatih 4:19 Anderson, Gillian 12:17 Canada, Ottawa 4:80 Jef Cornelis’s Bruce-Smith 3:5 a book review; Akin, Levan 7:29 Anderson, Laurie 4:13 Library of Congress, Washington documentaries 8:12-3 Awful Truth, The (1937) 9:42, 46 Akingbade, Ayo 8:31 Anderson, Lindsay 9:6 1/2:14; 4:80; 6:81 Josephine Deckers’s Madeline’s Axiom 7:11 A Akinnuoye-Agbaje, Adewale 8:42 Anderson, Paul Thomas Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Madeline 6:8-9, 66(r) Ayeh, Jaygann 8:22 Abbas, Hiam 1/2:47; 12:35 Akinola, Segun 10:44 1/2:24, 38; 4:25; 11:31, 34 New York 1/2:45; 6:81 Flaherty Seminar 2019, Ayer, David 10:31 Abbasi, Ali Akrami, Jamsheed 11:83 Anderson, Wes 1/2:24, 36; 5:7; 11:6 National Library of Scotland Hamilton 10:14-5 Ayoade, Richard -

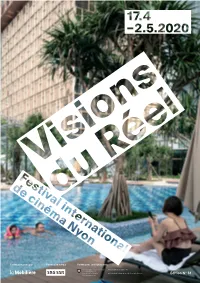

Vdr Prog 2020.Pdf

1 Partenaire principal Partenaire média Partenaires institutionnels Édition N° 51 2 1 Croquis du sinistre Editorial Fr Une édition qui non seulement doit En An edition that must not only forgo renoncer à son apparence physique, mais its physical form, but also exist in a world which, aussi exister dans un monde qui, tel un film de like a grade-Z science-fiction film, seems to be science-fiction de série Z, semble sur le point on the verge of disappearing in its known form… de disparaître dans sa forme connue… On 16 March, the entire Visions du Réel team Le 16 mars, toute l’équipe a amorcé la préparation began the preparation of a profoundly re-invented d’un Festival profondément ré-inventé, à distance, edition, working remotely, making great use à grand renfort de Skypes, de Zoom et de Google of Skype, Zoom and Google Docs, with frustration, Docs, s’énervant, s’enthousiasmant, sans réponses with enthusiasm, and sometimes without answers face à tant d’incertitudes. C’est là que se révèle, in the face of so much incertitude. It is here, in the au cœur de la crise, la beauté du collectif et les heart of the crisis, that the beauty of the collective énergies qui se complètent lorsque certain.e.s is revealed, the energies that complement each faiblissent. other when some weaken. Alors certes, VdR 2020 n’a pas lieu à la Place du So, of course, Visions du Réel 2020 is not taking Réel, dans les salles de cinéma, ou sous la tente. place at the Place du Réel, in the cinemas, or Mais il se tient résolument sur internet, dans in the tent. -

Your LIFF 2018 Guide

Welcome Welcome to your LIFF 2018 Guide. The global programme of the 32nd Leeds International Film Festival is all yours for exploring! You can find over 350 feature films, documentaries and shorts from 60 countries across five major programme sections: Official Selection, Cinema Versa, Fanomenon, Time Frames and Leeds Short Film Awards. You have over 300 eye-opening screenings and events to choose from at many of the city’s favourite venues and whether you want to see 6 or 60, we have great value passes and ticket offers available. We hope you have a wonderful experience at LIFF 2018 with 1000s of other film explorers! Contents LIFF 2018 Catalogue In the LIFF 2018 Catalogue you can Tickets / Map 4 discover more information about every Schedule 6 film presented in the programme. The Partners 11 catalogue will be available for FREE from Leeds Town Hall from 1 November, but Official Selection 14 there will be a limited supply so pick up Cinema Versa 34 your copy early!! Fanomenon 52 LIFF 2018 Online Time Frames 70 Leeds Short You can find the full LIFF 2018 programme online at leedsfilmcity.com where you 0113 376 0318 Film Awards 90 can also access the latest news including BOX OFFICE Index 100 guest announcements and award winners. To receive LIFF 2018 news first, join us on social media @leedsfilmfest and with # L I FF2018. Leeds International Screendance Competition Screendance Leeds International 3 Leeds Town Hall City Varieties Venues The Headrow, Leeds LS1 3AD Swan St, Leeds LS1 6LW Hyde Park Picture House Belgrave Music Hall 73 Brudenell -

GODARD FILM AS THEORY Volker Pantenburg Farocki/Godard

FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION FAROCKI/ GODARD FILM AS THEORY volker pantenburg Farocki/Godard Farocki/Godard Film as Theory Volker Pantenburg Amsterdam University Press The translation of this book is made possible by a grant from Volkswagen Foundation. Originally published as: Volker Pantenburg, Film als Theorie. Bildforschung bei Harun Farocki und Jean-Luc Godard, transcript Verlag, 2006 [isbn 3-899420440-9] Translated by Michael Turnbull This publication was supported by the Internationales Kolleg für Kulturtechnikforschung und Medienphilosophie of the Bauhaus-Universität Weimar with funds from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. IKKM BOOKS Volume 25 An overview of the whole series can be found at www.ikkm-weimar.de/schriften Cover illustration (front): Jean-Luc Godard, Histoire(s) du cinéma, Chapter 4B (1988-1998) Cover illustration (back): Interface © Harun Farocki 1995 Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Layout: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 90 8964 891 4 e-isbn 978 90 4852 755 7 doi 10.5117/9789089648914 nur 670 © V. Pantenburg / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2015 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustrations reproduced in this book. -

Farocki/Godard. Film As Theory

FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION FAROCKI/ GODARD FILM AS THEORY volker pantenburg Farocki/Godard Farocki/Godard Film as Theory Volker Pantenburg Amsterdam University Press The translation of this book is made possible by a grant from Volkswagen Foundation. Originally published as: Volker Pantenburg, Film als Theorie. Bildforschung bei Harun Farocki und Jean-Luc Godard, transcript Verlag, 2006 [isbn 3-899420440-9] Translated by Michael Turnbull This publication was supported by the Internationales Kolleg für Kulturtechnikforschung und Medienphilosophie of the Bauhaus-Universität Weimar with funds from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. IKKM BOOKS Volume 25 An overview of the whole series can be found at www.ikkm-weimar.de/schriften Cover illustration (front): Jean-Luc Godard, Histoire(s) du cinéma, Chapter 4B (1988-1998) Cover illustration (back): Interface © Harun Farocki 1995 Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Layout: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 90 8964 891 4 e-isbn 978 90 4852 755 7 doi 10.5117/9789089648914 nur 670 © V. Pantenburg / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2015 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustrations reproduced in this book. -

Sfreeweekl Ysince | De Cember

CHICAGO’SFREEWEEKLYSINCE | DECEMBER | DECEMBER CHICAGO’SFREEWEEKLYSINCE Year in review THIS WEEK CHICAGOREADER | DECEMBER | VOLUME NUMBER IN THIS ISSUE T R - CITYLIFE 16 FeatureTheworsteverday 27 Galil|ListenTheshrinking 03 TransportationLightfoot’s inChicagotheaterprovides ofmusicmediarequiresanew @ doneagoodjobofkeepingher theimpetusforabeloved defi nitionof“overlooked” promisetopromotemobility quirkyholidayshow buteventhestrictestcriteria PTB ADVERTISING EC -- - @ STAFFING CHANGES justicewithoneglaring 17 Review TheLightinthe admitavastunexploredtrove S K KH AT THE READER exception PiazzashinesatLyric ofriches CL C @ 18 ShowsThebestofChicago 28 ShowsofnoteAvreeaylRa S K MEP M KEEN EYED READERS of NEWS& theaterinputthe andTimeMachineAntiFlag TD SDP F spotlightonreshapingold TamaSumo&Lakutiandmore KR VPS our masthead will notice POLITICS narrativesandfalsehistory thisweek CEBW A M several changes we’d like AEJL CR M 04 Joravsky|PoliticsAsthe 19 DanceThebestmomentsin 31 TheSecretHistoryof SWDI T P to acknowledge this week. teensturntothetwentiesit’s dancethisyearfocusedonthe ChicagoMusicHard BJMS SAR After 20 years with the astruggletofi ndcheerinthe powerofcommunity workingcountryrockersthe SWM L M-H DLG L S Reader, Kate Schmidt is gloom 20 PlaysofNote America’s Moondogsneverreleasedtheir EA CSM stepping away from her role 07 Dukmasova|NewsAnight BestOutcastToyisheartfelt onlyalbum S N L W R as deputy editor to pursue spentrevelingintheabsurdity andfunnyTheMysteryof 32 EarlyWarningsSteveAoki -

Touching the Virgin. on the Politics of Intimacy in Jean-Luc Godard's Hail

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Emotion, Space and Society 13 (2014) 134e139 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Emotion, Space and Society journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/emospa Touching the Virgin. On the politics of intimacy in Jean-Luc Godard’s Hail Maryq Stefan Kristensen* Université de Genève, Unité d’histoire de l’art, Uni Dufour, 1211 Genève 4, Switzerland article info abstract Article history: This paper is guided by a conviction common to Godard and Merleau-Ponty: namely, that the special Received 13 May 2013 power of art is its ability to show up for us the invisible, what was previously unseen, and thereby to Received in revised form shape intimately, to transform, our own perceptions of the world. Art can thereby bring us into a more 4 December 2013 intimate contact with reality. With reference especially to Godard’s film Hail Mary, the paper argues that Accepted 6 December 2013 Godard distinguishes between two ways of approaching the human body: on the one hand, it can be Available online 4 January 2014 approached as prostituted thing e which has the effect of developing in the prostituted person a kind of absence to herself and to others, a dispossession of herself and an anesthesia to her own and others’ Keywords: e Jean-Luc Godard affective life. On the other hand, the human body can be approached as sacredly human in which case Maurice Merleau-Ponty we will touch that body very differently, expressing our presence to its embodied divinity precisely by Philosophy of perception withdrawing our touch and leaving space for its own desires. -

Love, Death and the Search for Community in William Gaddis And

Histoire(s) of Art and the Commodity: Love, Death, and the Search for Community in William Gaddis and Jean-Luc Godard Damien Marwood Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Discipline of English and Creative Writing The University of Adelaide December 2013 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................... iii Declaration............................................................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................... v Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 3 Methodology ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Topography ........................................................................................................................................ 11 Godard, Gaddis .................................................................................................................................. 17 Commodity, Catastrophe: the Artist Confined to Earth ........................................................................... 21 Satanic and Childish Commerce / Art and Culture ............................................................................ -

GODARD and the CINEMATIC ESSAY by Charles Richard Warner

RESEARCH IN THE FORM OF A SPECTACLE: GODARD AND THE CINEMATIC ESSAY by Charles Richard Warner, Jr. B.A., Georgetown College, 2000 M.A., Emory University, 2004 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2011 i UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Charles Richard Warner, Jr. It was defended on September 28, 2010 and approved by Lucy Fischer, Distinguished Professor, Department of English Randalle Halle, Klaus Jones Professor, Department of German Marcia Landy, Distinguished Professor, Department of English Colin MacCabe, Distinguished University Professor, Department of English Daniel Morgan, Assistant Professor, Department of English Dissertation Advisor: Adam Lowenstein, Associate Professor, Department of English ii Copyright © by Rick Warner 2011 iii RESEARCH IN THE FORM OF A SPECTACLE: GODARD AND THE CINEMATIC ESSAY Charles Richard Warner, Jr., PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2011 This dissertation is a study of the aesthetic, political, and ethical dimensions of the essay form as it passes into cinema – particularly the modern cinema in the aftermath of the Second World War – from literary and philosophic sources. Taking Jean-Luc Godard as my main case, but encompassing other important figures as well (including Agnès Varda, Chris Marker, and Guy Debord), I show how the cinematic essay is uniquely equipped to conduct an open-ended investigation into the powers and limits of film and other audio- visual manners of expression. I provide an analysis of the cinematic essay that illuminates its working principles in two crucial respects. -

THE IMAGE BOOK a Film by Jean-Luc Godard

THE IMAGE BOOK A film by Jean-Luc Godard ** Special Palme d’Or | 2018 Cannes Film Festival** **Official Selection | 2018 Toronto International Film Festival** **Official Selection | 2018 New York Film Festival** **Official Selection | 2018 San Sebastian Film Festival** Country: Switzerland / France Languages: English, French, Arabic, Italian Run Time: 84 minutes, Color, DCP. 7.1 Sound Publicity Contacts: Courtney Ott, [email protected] Nico Chapin, [email protected] David Ninh, [email protected] Distributor Contact: Graham Swindoll, [email protected] Kino Lorber, Inc., 333 West 39 St. Suite 503, New York, NY 10018, (212) 629-6880 Do you still remember how long ago we trained our thoughts? Most often we’d start from a dream… We wondered how, in total darkness colours of such intensity could emerge within us. In a soft low voice Saying great things, Surprising, deep and accurate matters. Like a bad dream written on a stormy night Under western eyes The lost paradises War is here The legendary Jean-Luc Godard adds to his influential, iconoclastic legacy with this provocative collage film essay, a vast ontological inquiry into the history of the moving image and a commentary on the contemporary world. Winner of the first Special Palme d'Or to be awarded in the history of the Cannes Film Festival, Jean-Luc Godard's Le livre d'image is another extraordinary addition to the French master's vast filmography. Ever the iconoclast and always the enquirer, Godard eschews actors and any pretence of narrative in this dazzling and brilliant film essay. Displaying an encyclopedic grasp of cinema and its history, Godard pieces together fragments and clips them from some of the greatest films of the past, then digitally alters, bleaches, and washes them, all in the service of reflecting on what he sees in front of him and what he makes of the dissonance that surrounds him.