Love, Death and the Search for Community in William Gaddis And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Image – Action – Space

Image – Action – Space IMAGE – ACTION – SPACE SITUATING THE SCREEN IN VISUAL PRACTICE Luisa Feiersinger, Kathrin Friedrich, Moritz Queisner (Eds.) This publication was made possible by the Image Knowledge Gestaltung. An Interdisciplinary Laboratory Cluster of Excellence at the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (EXC 1027/1) with financial support from the German Research Foundation as part of the Excellence Initiative. The editors like to thank Sarah Scheidmantel, Paul Schulmeister, Lisa Weber as well as Jacob Watson, Roisin Cronin and Stefan Ernsting (Translabor GbR) for their help in editing and proofreading the texts. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No-Derivatives 4.0 License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Copyrights for figures have been acknowledged according to best knowledge and ability. In case of legal claims please contact the editors. ISBN 978-3-11-046366-8 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-046497-9 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-046377-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018956404 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche National bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2018 Luisa Feiersinger, Kathrin Friedrich, Moritz Queisner, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com, https://www.doabooks.org and https://www.oapen.org. Cover illustration: Malte Euler Typesetting and design: Andreas Eberlein, aromaBerlin Printing and binding: Beltz Bad Langensalza GmbH, Bad Langensalza Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Inhalt 7 Editorial 115 Nina Franz and Moritz Queisner Image – Action – Space. -

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum Rivette: Texts and Interviews (editor, 1977) Orson Welles: A Critical View, by André Bazin (editor and translator, 1978) Moving Places: A Life in the Movies (1980) Film: The Front Line 1983 (1983) Midnight Movies (with J. Hoberman, 1983) Greed (1991) This Is Orson Welles, by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich (editor, 1992) Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995) Movies as Politics (1997) Another Kind of Independence: Joe Dante and the Roger Corman Class of 1970 (coedited with Bill Krohn, 1999) Dead Man (2000) Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000) Abbas Kiarostami (with Mehrmax Saeed-Vafa, 2003) Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (coedited with Adrian Martin, 2003) Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (2004) Discovering Orson Welles (2007) The Unquiet American: Trangressive Comedies from the U.S. (2009) Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Film Culture in Transition Jonathan Rosenbaum the university of chicago press | chicago and london Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote for many periodicals (including the Village Voice, Sight and Sound, Film Quarterly, and Film Comment) before becoming principal fi lm critic for the Chicago Reader in 1987. Since his retirement from that position in March 2008, he has maintained his own Web site and continued to write for both print and online publications. His many books include four major collections of essays: Placing Movies (California 1995), Movies as Politics (California 1997), Movie Wars (a cappella 2000), and Essential Cinema (Johns Hopkins 2004). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. -

Samuel Beckett's Peristaltic Modernism, 1932-1958 Adam

‘FIRST DIRTY, THEN MAKE CLEAN’: SAMUEL BECKETT’S PERISTALTIC MODERNISM, 1932-1958 ADAM MICHAEL WINSTANLEY PhD THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND RELATED LITERATURE MARCH 2013 1 ABSTRACT Drawing together a number of different recent approaches to Samuel Beckett’s studies, this thesis examines the convulsive narrative trajectories of Beckett’s prose works from Dream of Fair to Middling Women (1931-2) to The Unnamable (1958) in relation to the disorganised muscular contractions of peristalsis. Peristalsis is understood here, however, not merely as a digestive process, as the ‘propulsive movement of the gastrointestinal tract and other tubular organs’, but as the ‘coordinated waves of contraction and relaxation of the circular muscle’ (OED). Accordingly, this thesis reconciles a number of recent approaches to Beckett studies by combining textual, phenomenological and cultural concerns with a detailed account of Beckett’s own familiarity with early twentieth-century medical and psychoanalytical discourses. It examines the extent to which these discourses find a parallel in his work’s corporeal conception of the linguistic and narrative process, where the convolutions, disavowals and disjunctions that function at the level of narrative and syntax are persistently equated with medical ailments, autonomous reflexes and bodily emissions. Tracing this interest to his early work, the first chapter focuses upon the masturbatory trope of ‘dehiscence’ in Dream of Fair to Middling Women, while the second examines cardiovascular complaints in Murphy (1935-6). The third chapter considers the role that linguistic constipation plays in Watt (1941-5), while the fourth chapter focuses upon peristalsis and rumination in Molloy (1947). The penultimate chapter examines the significance of epilepsy, dilation and parturition in the ‘throes’ that dominate Malone Dies (1954-5), whereas the final chapter evaluates the significance of contamination and respiration in The Unnamable (1957-8). -

Select Letters of Percy Bysshe Shelley

ENGLISH CLÀSSICS The vignette, representing Shelleÿs house at Great Mar lou) before the late alterations, is /ro m a water- colour drawing by Dina Williams, daughter of Shelleÿs friend Edward Williams, given to the E ditor by / . Bertrand Payne, Esq., and probably made about 1840. SELECT LETTERS OF PERCY BYSSHE SHELLEY EDITED WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY RICHARD GARNETT NEW YORK D.APPLETON AND COMPANY X, 3, AND 5 BOND STREET MDCCCLXXXIII INTRODUCTION T he publication of a book in the series of which this little volume forms part, implies a claim on its behalf to a perfe&ion of form, as well as an attradiveness of subjeâ:, entitling it to the rank of a recognised English classic. This pretensión can rarely be advanced in favour of familiar letters, written in haste for the information or entertain ment of private friends. Such letters are frequently among the most delightful of literary compositions, but the stamp of absolute literary perfe&ion is rarely impressed upon them. The exceptions to this rule, in English literature at least, occur principally in the epistolary litera ture of the eighteenth century. Pope and Gray, artificial in their poetry, were not less artificial in genius to Cowper and Gray ; but would their un- their correspondence ; but while in the former premeditated utterances, from a literary point of department of composition they strove to display view, compare with the artifice of their prede their art, in the latter their no less successful cessors? The answer is not doubtful. Byron, endeavour was to conceal it. Together with Scott, and Kcats are excellent letter-writers, but Cowper and Walpole, they achieved the feat of their letters are far from possessing the classical imparting a literary value to ordinary topics by impress which they communicated to their poetry. -

What Literature Knows: Forays Into Literary Knowledge Production

Contributions to English 2 Contributions to English and American Literary Studies 2 and American Literary Studies 2 Antje Kley / Kai Merten (eds.) Antje Kley / Kai Merten (eds.) Kai Merten (eds.) Merten Kai / What Literature Knows This volume sheds light on the nexus between knowledge and literature. Arranged What Literature Knows historically, contributions address both popular and canonical English and Antje Kley US-American writing from the early modern period to the present. They focus on how historically specific texts engage with epistemological questions in relation to Forays into Literary Knowledge Production material and social forms as well as representation. The authors discuss literature as a culturally embedded form of knowledge production in its own right, which deploys narrative and poetic means of exploration to establish an independent and sometimes dissident archive. The worlds that imaginary texts project are shown to open up alternative perspectives to be reckoned with in the academic articulation and public discussion of issues in economics and the sciences, identity formation and wellbeing, legal rationale and political decision-making. What Literature Knows The Editors Antje Kley is professor of American Literary Studies at FAU Erlangen-Nürnberg, Germany. Her research interests focus on aesthetic forms and cultural functions of narrative, both autobiographical and fictional, in changing media environments between the eighteenth century and the present. Kai Merten is professor of British Literature at the University of Erfurt, Germany. His research focuses on contemporary poetry in English, Romantic culture in Britain as well as on questions of mediality in British literature and Postcolonial Studies. He is also the founder of the Erfurt Network on New Materialism. -

First Love, a Novella Part One Illustrated Volume 27 the Last Marriage of Editor Lily Hibberd Published by Ellikon Press 2009 Space and Time John C

Lily Hibberd First Love A novella Part one Illustrated volume Edited by Lily Hibberd Contents 11 Preface 15 Ice, time, desire Lily Hibberd First Love, a novella Part one illustrated volume 27 The Last Marriage of Editor Lily Hibberd Published by Ellikon Press 2009 Space and Time John C. Welchman Printed by Ellikon Fine Printers 384 George Street, Fitzroy Victoria 3065 Australia 42 Bibliography Telephone: +61 3 9417 3121 Designed by Warren Taylor © Copyright of all text is held by the authors Lily Hibberd and John C. Welchman, and copyright of all images is held by the artist, Lily Hibberd. This publication and its format and design are copyright of the editor and designer. All rights reserved. Artworks from the exhibition First Love, 2009 Lily Hibberd is a lecturer in the Fine Art Department, Faculty of Art & Design, Monash University, and is represented by Karen Woodbury Gallery, Melbourne. The production of this volume coincides with the solo exhibition of First Love at GRANTPIRRIE gallery, Sydney, in June 2009, and was facilitated with the kind assistance of gallery staff. This book was created because of the encouragement and generosity of John C. Welchman, Anne Marsh, Lois Ellis, and Hélène 4-7 Photoluminescent oil Delta time Cixous. paintings on canvas Celestial navigation Available for sale. Contact GRANTPIRRIE Gallery, Sydney. grantpirrie.com Gravity of light National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Lunar mirror Author: Hibberd, Lily, 1972- Title: First love. Part one : illustrated volume / Lily Hibberd. 10-34 Ice Mirror 10 works selected ISBN: 9781921179549 (pbk.) Notes: Bibliography. Oil paintings on from 13 in the series, Subjects: Time--Philosophy. -

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960S

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s By Zachary Saltz University of Kansas, Copyright 2011 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Film and Media Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts ________________________________ Dr. Michael Baskett ________________________________ Dr. Chuck Berg Date Defended: 19 April 2011 ii The Thesis Committee for Zachary Saltz certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts Date approved: 19 April 2011 iii ABSTRACT The Green Sheet was a bulletin created by the Film Estimate Board of National Organizations, and featured the composite movie ratings of its ten member organizations, largely Protestant and represented by women. Between 1933 and 1969, the Green Sheet was offered as a service to civic, educational, and religious centers informing patrons which motion pictures contained potentially offensive and prurient content for younger viewers and families. When the Motion Picture Association of America began underwriting its costs of publication, the Green Sheet was used as a bartering device by the film industry to root out municipal censorship boards and legislative bills mandating state classification measures. The Green Sheet underscored tensions between film industry executives such as Eric Johnston and Jack Valenti, movie theater owners, politicians, and patrons demanding more integrity in monitoring changing film content in the rapidly progressive era of the 1960s. Using a system of symbolic advisory ratings, the Green Sheet set an early precedent for the age-based types of ratings the motion picture industry would adopt in its own rating system of 1968. -

The Language of Emotion in Godard's Films Anuja Madan (Cineaction 80

The Language of Emotion in Godard's Films Anuja Madan (Cineaction 80 2010) So, to the question ʻWhat is Cinema?ʼ, I would reply: the expression of lofty sentiments. —Godard, in an essay 1 Nana: Isnʼt love the only truth?2 Emotion in the New Wave films is a fraught concept. Critics like Raymond Durgnat have commented that the New Wave films are characterized by emotional “dryness,” but such a view fails to engage with the complexity of the films.3 In what may seem like a paradoxical statement, these films display a passionate concern for the status of emotional life while being simultaneously engaged in the critique of emotion. This paper seeks to discuss the complex dynamics of emotion in three of Jean-Luc Godardʼs films—Vivre Sa Vie (My Life to Live, 1962), Alphaville, une Étrange aventure de Lemmy Caution (Alphaville, A Strange Adventure of Lemmy Caution, 1965) and Week End (1967). All of them belong to the fertile period of the 60s in which Godardʼs aesthetic strategies became increasingly daring. These will be examined in relation to some of his critical writings. An important paradigm within which Godardʼs films will be analyzed is that of cinemaʼs relationship to reality. A foundational principle of the New Wave was the faith in the intrinsic realism of the cinema, something Bazin had expounded upon. However, according to Godard, Bazinʼs model of cinema was novelistic, the realist description of relationships existent elsewhere. In his model, the director constructs his film, dialogue, and mise-en- scene, at every point: Reality is formed as the camera is framing it. -

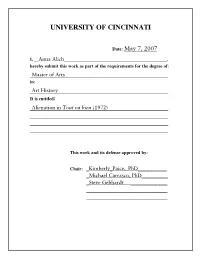

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: May 7, 2007 I, __Anna Alich_____________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: Art History It is entitled: Alienation in Tout va bien (1972) This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _Kimberly_Paice, PhD___________ _Michael Carrasco, PhD__________ _Steve Gebhardt ______________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Alienation in Jean-Luc Godard’s Tout Va Bien (1972) A thesis presented to the Art History Faculty of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning University of Cincinnati in candidacy for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Anna Alich May 2007 Advisor: Dr. Kimberly Paice Abstract Jean-Luc Godard’s (b. 1930) Tout va bien (1972) cannot be considered a successful political film because of its alienated methods of film production. In chapter one I examine the first part of Godard’s film career (1952-1967) the Nouvelle Vague years. Influenced by the events of May 1968, Godard at the end of this period renounced his films as bourgeois only to announce a new method of making films that would reflect the au courant French Maoist politics. In chapter two I discuss Godard and the Dziga Vertov Group’s last film Tout va bien. This film displays a marked difference in style from Godard’s earlier films, yet does not display a clear understanding of how to make a political film of this measure without alienating the audience. In contrast to this film, I contrast Guy Debord’s (1931-1994) contemporaneous film The Society of the Spectacle (1973). As a filmmaker Debord successfully dealt with alienation in film. -

Waiting for Godot and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead Axel KRUSI;

SYDNEY STUDIES Tragicomedy and Tragic Burlesque: Waiting for Godot and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead AxEL KRUSI; When Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead appeared at the .Old Vic theatre' in 1967, there was some suspicion that lack of literary value was one reason for the play's success. These doubts are repeated in the revised 1969 edition of John Russell Taylor's standard survey of recent British drama. The view in The Angry Theatre is that Stoppard lacks individuality, and that Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead is a pale imitation of the theatre of the absurd, wrillen in "brisk, informal prose", and with a vision of character and life which seems "a very small mouse to emerge from such an imposing mountain".l In contrast, Jumpers was received with considerable critical approval. Jumpers and Osborne's A Sense of Detachment and Storey's Life Class might seem to be evidence that in the past few years the new British drama has reached maturity as a tradition of dramatic forms aitd dramatic conventions which exist as a pattern of meaningful relationships between plays and audiences in particular theatres.2 Jumpers includes a group of philosophical acrobats, and in style and meaning seems to be an improved version of Stoppard's trans· lation of Beckett's theatre of the absurd into the terms of the conversation about the death of tragedy between the Player and Rosencrantz: Player Why, we grow rusty and you catch us at the very point of decadence-by this time tomorrow we might have forgotten every thing we ever knew. -

Myth-Making and the Novella Form in Denis Johnson's Train Dreams

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-15-2015 A Fire Stronger than God: Myth-making and the Novella Form in Denis Johnson's Train Dreams Chinh Ngo University of New Orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Ngo, Chinh, "A Fire Stronger than God: Myth-making and the Novella Form in Denis Johnson's Train Dreams" (2015). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1982. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1982 This Thesis-Restricted is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis-Restricted in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis-Restricted has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Fire Stronger than God: Myth-making and the Novella Form in Denis Johnson's Train Dreams A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Teaching by Chinh Ngo B.A. -

Retrospektive Viennale 1998 CESTERREICHISCHES FILM

Retrospektive Viennale 1998 CESTERREICHISCHES FILM MUSEUM Oktober 1998 RETROSPEKTIVE JEAN-LUC GODARD Das filmische Werk IN ZUSAMMENARBEIT MIT BRITISH FILM INSTITUTE, LONDON • CINEMATHEQUE DE TOULOUSE • LA CINl-MATHfeQUE FRAN^AISE, PARIS • CINIiMATHkQUE MUNICIPALE DE LUXEMBOURG. LUXEMBURG FREUNDE DER DEUTSCHEN KINEMATHEK. BERLIN ■ INSTITUT FRAN^AIS DB VIENNE MINISTERE DES AFFAIRES ETRANGERES, PARIS MÜNCHNER STADTMUSEUM - FILMMUSEUM NATIONAL FILM AND TELEVISION ARCHIVE, LONDON STIFTUNG PRO HEI.VETIA, ZÜRICH ZYKLISCHES PROGRAMM - WAS IST FILM * DIE GESCHICHTE DES FILMISCHEN DENKENS IN BEISPIELEN MIT FILMEN VON STAN BRAKHAGE • EMILE COHL • BRUCE CONNER • WILLIAM KENNEDY LAURIE DfCKSON - ALEKSANDR P DOVSHENKO • MARCEL DUCHAMP • EDISON KINETOGRAPH • VIKING EGGELING; ROBERT J. FLAHERTY ROBERT FRANK • JORIS IVENS • RICHARD LEACOCK • FERNAND LEGER CIN^MATOGRAPHE LUMIERE • ETIENNE-JULES MAREY • JONAS MEKAS • GEORGES MELIUS • MARIE MENKEN • ROBERT NELSON • DON A. PENNEBAKER • MAN RAY • HANS RICHTER • LENI glEFENSTAHL • JACK SMITH • DZIGA VERTOV 60 PROGRAMME • 30 WOCHEN • JÄHRLICH WIEDERHOLT • JEDEN DIENSTAG ZWEI VORSTELLUNGEN Donnerstag, 1. Oktober 1998, 17.00 Uhr Marrfnuß sich den anderen leihen, sich jedoch Monsigny; Darsteller: Jean-Claude Brialy. UNE FEMME MARIEE 1964) Sonntag, 4. Oktober 1998, 19.00 Uhr Undurchsichtigkeit und Venvirrung. Seht, die Rea¬ Mittwoch, 7. Oktober 1998, 21.00 Uhr Raou! Coutard; Schnitt: Agnes Guiliemot; Die beiden vorrangigen Autoren der Gruppe Dziga sich selbst geben- Montaigne Sein Leben leben. Anne Colette, Nicole Berger Regie: Jean-Luc Godard; Drehbuch: Jean-Luc lität. metaphorisiert Godaiti nichtsonderlich inspi¬ Musik: Karl-Heinz Stockhausen, Franz Vertov. Jean-Luc Godard und Jean-Pierre Gönn, CHARLOTTE ET SON JULES (1958) VfVRE SA VIE. Die Heldin, die dies versucht: eine MASCULIN - FEMININ (1966) riert, em Strudel, in dem sich die Wege verlaufen.