THE IMAGE BOOK a Film by Jean-Luc Godard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Gioco' E Del 'Montaggio'

Magazine del Festival ricerche e progetti research and projects on FAM dell’Architettura sull’architettura e la città architecture and the city Del ‘gioco’ 51 e del ‘montaggio’ nella didattica e nella composizione Elvio Manganaro Del gioco e del montaggio Tommaso Brighenti Per gioco ma sul serio Gianluca Maestri Note sulle semantiche del gioco Francesco Zucconi Montaggio e anatopismo secondo Jean-Luc Godard Antonella Sbrilli Sette appunti su scatole di giochi, artisti e storie dell’arte Laura Scala La Vittoria sul Sole di Malevič: la dissoluzione della realtà Cosimo Monteleone Frank Lloyd Wright e il gioco dell’astrazione geometrica Amra Salihbegovic Apologia per un’architettura del gioco Elvio Manganaro “Montage, mon beau souci” Tamar Zinguer All’origine della Sandbox Enrico Bordogna Il ragazzo dello IUAV Giuseppe Tupputi Le architetture metropolitane di Paulo Mendes da Rocha.Tra concezione spaziale e ideazione strutturale Giuseppe Verterame Abitare lo spazio attraverso archetipi. Letture delle opere di Kahn e Mies DOI: 10.1283/fam/issn2039-0491/n51-2020 Magazine del Festival ricerche e progetti research and projects on FAM dell’Architettura sull’architettura e la città architecture and the city FAMagazine. Ricerche e progetti sull’architettura e la città Editore: Festival Architettura Edizioni, Parma, Italia ISSN: 2039-0491 Segreteria di redazione c/o Università di Parma Campus Scienze e Tecnologie Via G. P. Usberti, 181/a 43124 - Parma (Italia) Email: [email protected] www.famagazine.it Editorial Team Direzione Enrico Prandi, -

Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND SUBJECT INDEX Film review titles are also Akbari, Mania 6:18 Anchors Away 12:44, 46 Korean Film Archive, Seoul 3:8 archives of television material Spielberg’s campaign for four- included and are indicated by Akerman, Chantal 11:47, 92(b) Ancient Law, The 1/2:44, 45; 6:32 Stanley Kubrick 12:32 collected by 11:19 week theatrical release 5:5 (r) after the reference; Akhavan, Desiree 3:95; 6:15 Andersen, Thom 4:81 Library and Archives Richard Billingham 4:44 BAFTA 4:11, to Sue (b) after reference indicates Akin, Fatih 4:19 Anderson, Gillian 12:17 Canada, Ottawa 4:80 Jef Cornelis’s Bruce-Smith 3:5 a book review; Akin, Levan 7:29 Anderson, Laurie 4:13 Library of Congress, Washington documentaries 8:12-3 Awful Truth, The (1937) 9:42, 46 Akingbade, Ayo 8:31 Anderson, Lindsay 9:6 1/2:14; 4:80; 6:81 Josephine Deckers’s Madeline’s Axiom 7:11 A Akinnuoye-Agbaje, Adewale 8:42 Anderson, Paul Thomas Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Madeline 6:8-9, 66(r) Ayeh, Jaygann 8:22 Abbas, Hiam 1/2:47; 12:35 Akinola, Segun 10:44 1/2:24, 38; 4:25; 11:31, 34 New York 1/2:45; 6:81 Flaherty Seminar 2019, Ayer, David 10:31 Abbasi, Ali Akrami, Jamsheed 11:83 Anderson, Wes 1/2:24, 36; 5:7; 11:6 National Library of Scotland Hamilton 10:14-5 Ayoade, Richard -

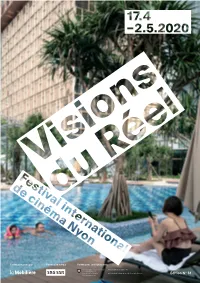

Vdr Prog 2020.Pdf

1 Partenaire principal Partenaire média Partenaires institutionnels Édition N° 51 2 1 Croquis du sinistre Editorial Fr Une édition qui non seulement doit En An edition that must not only forgo renoncer à son apparence physique, mais its physical form, but also exist in a world which, aussi exister dans un monde qui, tel un film de like a grade-Z science-fiction film, seems to be science-fiction de série Z, semble sur le point on the verge of disappearing in its known form… de disparaître dans sa forme connue… On 16 March, the entire Visions du Réel team Le 16 mars, toute l’équipe a amorcé la préparation began the preparation of a profoundly re-invented d’un Festival profondément ré-inventé, à distance, edition, working remotely, making great use à grand renfort de Skypes, de Zoom et de Google of Skype, Zoom and Google Docs, with frustration, Docs, s’énervant, s’enthousiasmant, sans réponses with enthusiasm, and sometimes without answers face à tant d’incertitudes. C’est là que se révèle, in the face of so much incertitude. It is here, in the au cœur de la crise, la beauté du collectif et les heart of the crisis, that the beauty of the collective énergies qui se complètent lorsque certain.e.s is revealed, the energies that complement each faiblissent. other when some weaken. Alors certes, VdR 2020 n’a pas lieu à la Place du So, of course, Visions du Réel 2020 is not taking Réel, dans les salles de cinéma, ou sous la tente. place at the Place du Réel, in the cinemas, or Mais il se tient résolument sur internet, dans in the tent. -

Your LIFF 2018 Guide

Welcome Welcome to your LIFF 2018 Guide. The global programme of the 32nd Leeds International Film Festival is all yours for exploring! You can find over 350 feature films, documentaries and shorts from 60 countries across five major programme sections: Official Selection, Cinema Versa, Fanomenon, Time Frames and Leeds Short Film Awards. You have over 300 eye-opening screenings and events to choose from at many of the city’s favourite venues and whether you want to see 6 or 60, we have great value passes and ticket offers available. We hope you have a wonderful experience at LIFF 2018 with 1000s of other film explorers! Contents LIFF 2018 Catalogue In the LIFF 2018 Catalogue you can Tickets / Map 4 discover more information about every Schedule 6 film presented in the programme. The Partners 11 catalogue will be available for FREE from Leeds Town Hall from 1 November, but Official Selection 14 there will be a limited supply so pick up Cinema Versa 34 your copy early!! Fanomenon 52 LIFF 2018 Online Time Frames 70 Leeds Short You can find the full LIFF 2018 programme online at leedsfilmcity.com where you 0113 376 0318 Film Awards 90 can also access the latest news including BOX OFFICE Index 100 guest announcements and award winners. To receive LIFF 2018 news first, join us on social media @leedsfilmfest and with # L I FF2018. Leeds International Screendance Competition Screendance Leeds International 3 Leeds Town Hall City Varieties Venues The Headrow, Leeds LS1 3AD Swan St, Leeds LS1 6LW Hyde Park Picture House Belgrave Music Hall 73 Brudenell -

Sfreeweekl Ysince | De Cember

CHICAGO’SFREEWEEKLYSINCE | DECEMBER | DECEMBER CHICAGO’SFREEWEEKLYSINCE Year in review THIS WEEK CHICAGOREADER | DECEMBER | VOLUME NUMBER IN THIS ISSUE T R - CITYLIFE 16 FeatureTheworsteverday 27 Galil|ListenTheshrinking 03 TransportationLightfoot’s inChicagotheaterprovides ofmusicmediarequiresanew @ doneagoodjobofkeepingher theimpetusforabeloved defi nitionof“overlooked” promisetopromotemobility quirkyholidayshow buteventhestrictestcriteria PTB ADVERTISING EC -- - @ STAFFING CHANGES justicewithoneglaring 17 Review TheLightinthe admitavastunexploredtrove S K KH AT THE READER exception PiazzashinesatLyric ofriches CL C @ 18 ShowsThebestofChicago 28 ShowsofnoteAvreeaylRa S K MEP M KEEN EYED READERS of NEWS& theaterinputthe andTimeMachineAntiFlag TD SDP F spotlightonreshapingold TamaSumo&Lakutiandmore KR VPS our masthead will notice POLITICS narrativesandfalsehistory thisweek CEBW A M several changes we’d like AEJL CR M 04 Joravsky|PoliticsAsthe 19 DanceThebestmomentsin 31 TheSecretHistoryof SWDI T P to acknowledge this week. teensturntothetwentiesit’s dancethisyearfocusedonthe ChicagoMusicHard BJMS SAR After 20 years with the astruggletofi ndcheerinthe powerofcommunity workingcountryrockersthe SWM L M-H DLG L S Reader, Kate Schmidt is gloom 20 PlaysofNote America’s Moondogsneverreleasedtheir EA CSM stepping away from her role 07 Dukmasova|NewsAnight BestOutcastToyisheartfelt onlyalbum S N L W R as deputy editor to pursue spentrevelingintheabsurdity andfunnyTheMysteryof 32 EarlyWarningsSteveAoki -

Fifteen Lessons with Godard

SEEING FROM SCRATCH ◊ by RICHARD DIENST with 15 LESSONS WITH GODARD ◊ THE POSTCARD GAME SEEING FROM SCRATCH ◊ by RICHARD DIENST with 15 LESSONS WITH GODARD ◊ THE POSTCARD GAME SEEING FROM SCRATCH ◊ by RICHARD DIENST with 15 LESSONS WITH GODARD ◊ THE POSTCARD GAME SEEING FROM SCRATCH ◊ by RICHARD DIENST with 15 LESSONS WITH GODARD ◊ THE POSTCARD GAME SEEING FROM SCRATCH ◊ by RICHARD DIENST with 15 LESSONS WITH GODARD ◊ THE POSTCARD GAME SEEING FROM SCRATCH ◊ by RICHARD DIENST with 15 LESSONS WITH GODARD ◊ THE POSTCARD GAME SEEING FROM SCRATCH ◊ by RICHARD DIENST with 15 LESSONS WITH GODARD ◊ THE POSTCARD GAME SEEING FROM SCRATCH ◊ by RICHARD DIENST with 15 LESSONS WITH GODARD ◊ THE POSTCARD GAME SEEING FROM SCRATCH ◊ by RICHARD DIENST with 15 LESSONS WITH GODARD ◊ THE POSTCARD GAME SEEING FROM SCRATCH ◊ by RICHARD DIENST with 15 LESSONS WITH GODARD ◊ THE POSTCARD GAME SEEING FROM SCRATCH ◊ by RICHARD DIENST with 15 LESSONS WITH GODARD ◊ THE POSTCARD GAME SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH with THE POSTCARD GAME THE POSTCARD GAME CABOOSE SEEING FROM SCRATCH ◊ 15 LESSONS WITH GODARD with THE POSTCARD GAME ◊ RICHARD DIENST CABOOSE ◊ MONTREAL SEEING FROM SCRATCH 1 INTERMISSION 99 THE POSTCARD GAME 103 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 131 COLOPHON 132 SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH SEEING FROM SCRATCH LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN LEARN 3 In 1979 Jean-Luc Godard filled a page ofCahiers du Cinéma with the word LEARN (APPRENDRE).1 It appears twenty-two times. -

LIFF 2018 Catalogue

Welcome LEEDS INTERNATIONAL Welcome to FILM FESTIVAL the LIFF 2018 Catalogue The 32nd Leeds International Film Festival is presented in association with Leeds 2023, a partnership that has made possible the most extensive and diverse celebration of film in the city yet. From world premieres of films made in Leeds and Yorkshire to programmes chosen from over 6,000 films submitted from 109 countries, This festival’s winning short films may LIFF 2018 represents the epic scale and incredible qualify for consideration for the variety of global filmmaking culture. A big thank you to everyone who has contributed to the development of LIFF 2018 and to our audiences for their support of film culture in Leeds. Contents Partners 5 LIFF 2018 Team 6 Official Selection 9 Cinema Versa 63 Fanomenon 101 Time Frames 141 ENTRY REQUIREMENTS Leeds Short Film Awards 185 Oscars.org/Rules Index 243 2 3 Partners Partners Presented by Leading Funders Leading Partners In Association with Major Partners Supporting Partners Sorry to Bother You 4 5 Team Director Leeds City Centre Box Office Staff Venue Assistants Chris Fell Adam Hogarty, Dena Marsh, Kate Parkin, Katy Adams, Lewis Anderson, Daria Arofikina, LIFF 2018 Production Manager Dean Ramsden, Helen Richmond, Shirley Shortall. Jonathan Atkinson, Natasha Audsley, Tom Jamie Cross Bache, Ross Baillie-Eames, Jack Beaumont, Communications Manager Venue Coordinators Sophie Bellová, Emma Bird, Angie Bourdillon, Nick Jones Sue Barnes, Laura Beddows, Alice Duggan, Simon Brett, Hannah Broadbent, Michael Programme Manager Nils Finken, Matt Goodband, Tom Kendall, Brough, Jenna Brown, Julie Carrack, Jess Carrier, Team Alex King Katie Lee, Melissa McVeigh, Joe Newberry, Peter Clarke, Jessie Clayton, Sarah Danaher, Development Managers Vicki Rolley, Natalie Walton, Sarah Wilson. -

13.Internationales Filmfestival

UNDER DOX internationales flmfestival dokument und experiment 13. 11—17 okt 2018 www.underdox-festival.de do 11.10. 19.00 inhalt filmmuseum Le livre d’image fr 12.10. 18.30 20.30 21.00 22.30 filmmuseum Cinema ★ português I: The School langfilme dokumente & experimente of Reis 04 ★ (Johann Lurf) 67 Armand Yervant Tufenkian & werkstatt Djamilia Don't Work Traces of 06 Ang Panahon ng Halimaw (Lav Diaz) Tamer Hassan kino Toi qui 1968-2018 Garden 08 Aufbruch (Ludwig Wüst) 67 Evelyn Rüsseler aka Bear Boy sa 13.10. 16.30 18.30 20.30 21.00 22.30 10 Black Mother (Khalik Allah) 68 Félix Rehm filmmuseum Cinema Ray & Liz 12 Dead Souls (Wang Bing) 68 Camilo Restrepo português II: 14 Djamilia (Aminatou Echard) 71 Evelyn Rüsseler aka Bear Boy Die 1980er 16 An Elephant Sitting Still (Hu Bo) 71 Brent Green Generation 18 The Green Fog (Guy Maddin, 72 Nicolas Boone werkstatt La muerte Manivelle Aufbruch Black Evan Johnson, Galen Johnson) 72 Philip Widmann kino del maestro The Bird and Mother 20 Invest in Failure (Norbert 75 Herbert Fell La sombra Us La bouche Pfaffenbichler) 75 Lukas Marxt de un dios Das Gestell 22 Jeannette – L’Enfance de Jeanne d’Arc 76 Francesca Scalisi & Mark Olexa so 14.10. 11.00 15.00 18.30 20.00 (Bruno Dumont) 76 Nan Wang kunstverein Dead Souls 24 Kalès (Laurent Van Lancker) 79 Sohrab Hura 26 Le livre d’image (Jean-Luc Godard) 79 Fadi [the fdz] Baki theatiner Jeannette, l’enfance 28 La muerte del maestro (José María 80 Billy Roisz de Jeanne Avilés) 80 Okin Cznupolowsky d’Arc 30 Ne travaille pas (1968–2018) (César 83 Laurence Favre filmmuseum Season of Vayssié) 83 Sara Cwynar the Devil 32 Playing Men (Matjaž Ivanišin) 84 Alex Gerbaulet werkstatt King Kong Kalès An Elephant 34 Ray & Liz (Richard Billingham) 84 Kate Tessa Lee & Tom Schön kino Kunstkabinett La Sombra Sitting Still 36 Traces of Garden (Wolfgang Lehmann) 87 Regina José Gilando 87 Bernhard Hetzenauer mo 15.10. -

Francesco Zucconi Assemblage and Anatopism According to Jean-Luc Godard

DOI: 10.1283/fam/issn2039-0491/n51-2020/322 Francesco Zucconi Assemblage and anatopism according to Jean-Luc Godard Abstract Frequently described as a reflection on the traumatic history of the 20th century, the cinema of Jean-Luc Godard has managed to call attention several times to the geographical atlas, forcing us to conceive the practi- ce of assemblage as an unceasing juxtaposition of different places. This article sets out to rethink his cinema as a large assemblage laboratory, where the spatial component of the image as well as the geographical and political ones are called into question. In speaking of assemblage, we turn to the concepts of “anachronism” and “anatopism”, the latter se- emingly never granted due theoretical prominence. Keywords Cinematic Editing — Anachronism — Anatopism Layouts of a thought in images In the autumn of 2019, the 89-year-old Franco-Swiss director Jean-Luc Godard was invited to present his latest film, The Image Book (2019), in the form of a multi-media visit at the premises of the Théâtre Nanterre- Amandiers, on the outskirts of Paris1. The idea to design an exhibition from a film might appear to be the umpteenth reflection on the relationship between the forms of the cinematic experience and that of the museum: a new episode of that “querelle des dispositifs” (Bellour 2012) which has so enlivened the theoretical and critical debate of recent years. Howev- er, those who know Godard also know that the only controversies which count are those launched by his films, by his stance; ingenious and difficult to totally marry into in equal measure. -

Migrant Thoughts Cinematographic Intersections

migrant thoughts cinematographic intersections ] hambre [ espacio cine experimental Migrant Thoughts : Cinematographic — Intersections / Nicole Brenez... [et al.] ; edition compilated by Florencia Incarbone ; Florencia Incarbone Sebastian Wiedemann. - 1st ed. - Sebastian Wiedemann Vicente López : Florencia Incarbone, 2020. 204 p. ; 20 x 14 cm. proofreading Mariano Blatt ISBN 978-987-86-7203-8 Alicia Di Stasio Mario Valledor 1. Film analysis. 2. Film criticism. I. Brenez, Nicole. II. Incarbone, Florencia, comp. translation III. Wiedemann, Sebastian, comp. Alicia Bermolen CDD 791.4361 Alejo Magariños Daniel Tunnard Sebastian Wiedemann design Micaela Blaustein font Alegreya Sans by Juan Pablo del Peral Prologue 7 — Migrant Thoughts. Images as a Gesture of Resistance florencia incarbone and sebastian wiedemann Interval 15 — Image, Fact, Action, and What Remains to Be Done nicole brenez Intersection I: Memory and Archive 53 — Marta Rodríguez: Memory and Resistance andrés bedoya ortiz 69 — Glaring Absence: Viral Archives in Albertina Carri’s Restos and Cuatreros jens andermann Intersection II: Literature and Philosophy 81 — Faces that Remain, Any Given Face. The Films of Pedro Costa and the Fictions of Maurice Blanchot carolina villada castro 91 — The Clearing in the Woods. Carelia: internacional con monumento, by Andrés Duque cloe masotta 111 — The Transformation of the Poetic Animal carlos m. videla Intersection III: Decolonizing the Image 131 — Karrabing: An Essay in Keywords tess lea and elizabeth a. povinelli 153 — Dy(e)ing is Not-Dying. Nova Paul’s Experimental Colour Film Polemic tessa laird Interval 163 — Improvisation. The Controlled Accident yann beauvais 190 — About the Authors la radicalidad de la im migrant thoughts. image as a gesture of resistance florencia incarbone and sebastian wiedemann To migrate is to move from one place to another, seeking to sustain the flow of life. -

Okcmoa Museum Films March 2019 Schedule

OKCMOA MUSEUM FILMS MARCH 2019 SCHEDULE JLG FOREVER BREATHLESS Jean-Luc Godard | 1960 | 90 min. | NR Thurs. Feb 28 @ 7:30 pm A jazzy, sexy, free-form homage to American genre film, Godard’s revolutionary debut launched the French New Wave movement and transformed film language. Screening on 35mm film. THE IMAGE BOOK Jean-Luc Godard | 2018 | 84 min. | NR Fri. March 1 @ 5:30 pm | Sat. March 2 @ 8 pm | Sun. March 3 @ 2 & 5:30 pm Winner of the Special Palme d’Or at the 2018 Cannes Film Festival, Godard’s latest is a sweeping film historical collage and a provocative commentary on the contemporary world. CONTEMPT Jean-Luc Godard | 1963 | 103 min. | NR Fri. March 1 @ 8 pm Godard’s most commercially successful film, Contempt is a brilliant study of marital breakdown, artistic compromise and the cinematic process, starring Brigitte Bardot and Michel Piccoli. PIERROT LE FOU Jean-Luc Godard | 1965 | 110 min. | NR Sat. March 1 @ 5:30 pm Jean-Paul Belmondo and Anna Karina play a pair of amoral lovers on the run in a stylish mash-up of consumerist satire, politics, and comic-book aesthetics. One of the New Wave’s aesthetic peaks. ____________________________________________________________________ THE COMPETITION Claire Simon | 2016 | 121 min. | NR Thurs. March 7 @ 5:30 & 8 pm Funny, penetrating and surprisingly suspenseful, this observational documentary from French filmmaker Claire Simon offers insights into the highly selective admissions process of one the world’s most prestigious film schools. THE WILD PEAR TREE Nuri Bilge Ceylan | 2018 | 188 min. | NR Fri. March 8 @ 7 pm | Sat. -

SIN-Booklet-Design-Print.Pdf

14, 15, 16 رام ﷲ ّ ﻏﺰة ﻣﺎرﺳﻴﻠﻴﺎ ﻟﻔﻦ اﻟﻔﻴﺪﻳﻮ واﻷداء Special Thanks To Film Screening in collaboration with شكر خاص لـ عروض األفالم بالتعاون مع Jean-Luc Godard for his trust جون لوك غودار ملنحنا ثقته Yazid Anani Zeit ou Zaatar زيت وزعرت يزيد عناين Nisreen Naffa’ Top Corner توب كورنر نرسين نفاع Sally Abu baker Jawwal Telecommunication Center معرض جوال – وسط البلد سايل أبو بكر Eid Dwikat Karameh Pastry حلويات كرامة عيد دويكات Fabrice Aragno Baladna Ice Cream بوظة بلدنا فابريكا أراغنو Jean-Paul Battaggia Sbitany Hitech رشكة سبيتاين جون-بول باتايا Nicole Brenez Zughaier Sun Sun ّزغي بيكول برينزي Raed Issa Zughayer – Shoes & Fashion ّزغي – أزياء وأحذية رائد عيىس Yousef Mansour Bazar Company for Communications and General Services يوسف منصور ّ ارالزب لالتصاالت Nirmeen Safi European Pastries نرمني صايف حلويات أوروبا Raed Issa Liftawi Men's Wear رائد عيىس اللفتاوي لأللبسة الرجالية Birzeit University Dunia Exhibition جامعة بيزيت معرض دنيا Heba Hamarsheh Heliopolis Fashion هبة حمارشة هليوبولوس Tarteel Muammar Rukab’s Ice Cream ترتيل معمر بوظة ركب .Jawwal Co Saba Sandwiches رشكة جوال مطعم سابا Rula Rezeq روال رزق Birzeit University Museum الت ّ متحف جامعة بيزيت Issam Khaseeb ّمصم القيّ عصام خصيب التقن ّ ال ّرت يون: ضيّ ّ تحرير الرتجمة العربيّ ّ ّ تحرير الرت مون علىمو االختيار الجرافيك: الدهيثم حدّ ّويل جمة العربيّاء الجعبة، مهن ّ ة: هنا إرشيد اإلعالم: نسيق:مرام شادي طوطح، بكر، نايك حسن مسيلي،صفدي، نادر رشيف داغررسحان ة: عبد ّالر د أبو اد،حمدي ّةويلفريد ليجود ّ تحرير ترجمة الفيديو: خالد فن حمن أبو ّشم جمة االنجلزيية: مارغريت دباي: مارك الةمريسري، نايك