Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Soldier Fights for Three Separate but Sometimes Associated Reasons: for Duty, for Payment and for Cause

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stirling Online Research Repository The press and military conflict in early modern Scotland by Alastair J. Mann A soldier fights for three separate but sometimes associated reasons: for duty, for payment and for cause. Nathianiel Hawthorne once said of valour, however, that ‘he is only brave who has affections to fight for’. Those soldiers who are prepared most readily to risk their lives are those driven by political and religious passions. From the advent of printing to the present day the printed word has provided governments and generals with a means to galvanise support and to delineate both the emotional and rational reasons for participation in conflict. Like steel and gunpowder, the press was generally available to all military propagandists in early modern Europe, and so a press war was characteristic of outbreaks of civil war and inter-national war, and thus it was for those conflicts involving the Scottish soldier. Did Scotland’s early modern soldiers carry print into battle? Paul Huhnerfeld, the biographer of the German philosopher and Nazi Martin Heidegger, provides the curious revelation that German soldiers who died at the Russian front in the Second World War were to be found with copies of Heidegger’s popular philosophical works, with all their nihilism and anti-Semitism, in their knapsacks.1 The evidence for such proximity between print and combat is inconclusive for early modern Scotland, at least in any large scale. Officers and military chaplains certainly obtained religious pamphlets during the covenanting period from 1638 to 1651. -

A Memorial Volume of St. Andrews University In

DUPLICATE FROM THE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY, ST. ANDREWS, SCOTLAND. GIFT OF VOTIVA TABELLA H H H The Coats of Arms belong respectively to Alexander Stewart, natural son James Kennedy, Bishop of St of James IV, Archbishop of St Andrews 1440-1465, founder Andrews 1509-1513, and John Hepburn, Prior of St Andrews of St Salvator's College 1482-1522, cofounders of 1450 St Leonard's College 1512 The University- James Beaton, Archbishop of St Sir George Washington Andrews 1 522-1 539, who com- Baxter, menced the foundation of St grand-nephew and representative Mary's College 1537; Cardinal of Miss Mary Ann Baxter of David Beaton, Archbishop 1539- Balgavies, who founded 1546, who continued his brother's work, and John Hamilton, Arch- University College bishop 1 546-1 57 1, who com- Dundee in pleted the foundation 1880 1553 VOTIVA TABELLA A MEMORIAL VOLUME OF ST ANDREWS UNIVERSITY IN CONNECTION WITH ITS QUINCENTENARY FESTIVAL MDCCCCXI MCCCCXI iLVal Quo fit ut omnis Votiva pateat veluti descripta tabella Vita senis Horace PRINTED FOR THE UNIVERSITY BY ROBERT MACLEHOSE AND COMPANY LIMITED MCMXI GIF [ Presented by the University PREFACE This volume is intended primarily as a book of information about St Andrews University, to be placed in the hands of the distinguished guests who are coming from many lands to take part in our Quincentenary festival. It is accordingly in the main historical. In Part I the story is told of the beginning of the University and of its Colleges. Here it will be seen that the University was the work in the first instance of Churchmen unselfishly devoted to the improvement of their country, and manifesting by their acts that deep interest in education which long, before John Knox was born, lay in the heart of Scotland. -

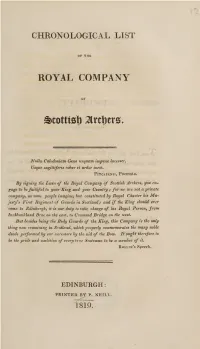

Chronological List of the Royal Company of Scottish Archers

CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF THE ROYAL COMPANY OF 2lrrt)er0. Nulla Caledoniam Gens unquarn impune laces set, Usque sagittiferis rohur et ardor inest. Pitcairnii, Poemata. By signing the Laws of the Royal Company of Scottish Archers, you en¬ gage to he faithful to your King and your Country ; for we are not a private company, as some people imagine, but constituted hy Royal Charter his Ma¬ jesty's First Regiment of Guards in Scotland; and if the King should ever come to Edinburgh, it is our duty to take charge of his Royal Person, from Inchbunkland Brae on the east, to Cramond Bridge on the west. But besides being the Body Guards of the King, this Company is the only thing now remaining in Scotland, which properly commemorates the many noble deeds performed by our ancestors by the aid of the Bow. It ought therefore to be the pride and ambition of every true Scotsman to be a member of it. Roslin’s Speech. EDINBURGH: PRINTED BY P. NEII.T.. 1819. PREFACE, T he first part of the following List, is not preserved in the handwriting of the Members themselves, and is not accurate with respect to dates; but the names are copied from the oldest Minute-books of the Company which have been preserved. The list from the 13th of May 1714, is copied from the Parchment Roll, which every Member subscribes with his own hand, in presence of the Council of the Company, when he receives his Diploma. Edinburgh, 1 5th July 1819* | f I LIST OF MEMBERS ADMITTED INTO THE ROYAL COMPANY OF SCOTTISH ARCHERS, FROM 1676, Extracted from Minute-books prior to the 13th of May 1714. -

Trophy of the Edinburgh Society of Bowlers George R Dalgleish*

Proc SocAntiq Scot, 120 (1990), 189-200, The 'Silver Jack' trophy of the Edinburgh Society of Bowlers George R Dalgleish* '. doucer folk wysing a-jee The by as bowls on Tamson's green.' Allan Ramsay ABSTRACT This paper presents descriptiona 18th-century ofan sporting trophy investigatesand historythe of the society to which it was presented. INTRODUCTION In April 1986, the National Museums of Scotland bought, from a silver dealer in London, a unique 18th-century bowling trophy. Known as the 'Silver Jack', it was originally presented as an annual trophy to the Edinburgh Society of Bowlers in 1771 (NMS registration MEQ1594). The year before the Museums acquired it, it had appeared in an auction of Important English and Continental Silver hel Christie'y dYorb w kNe n (Christie'i s s 1985 t 1167),lo . Enquiries int histore os th it f yo previous ownership have, unfortunately, proved inconclusive, although it does seem it was in the possession of a London collector some time prior to its export to America. Despit e lac th f elateko r provenanc e extremel e 'Jackar th e r w ' fo e y fortunat o havet e considerable contemporary evidenc originas it r efo l presentatio e Societth r whico fo yt d t nhan i relates. This article will presen detailea t d descriptio trophe th thed f no y an n investigat historys eit , settin t withigi contexna histore spore th th f Edinburgto n f i tyo Scotlandd han . DESCRIPTION (illus 1) trophe Th y comprise silvesa r bowl morr ,o e accurately 'jack',a flattenef ,o d spherical form9 ,7 mm in diameter by 67 mm in width. -

Directory for the City of Aberdeen

ABERDEEN CITY LIBRARIES Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/directoryforcity185556uns mxUij €i% of ^krtimt \ 1855-56. TO WHICH tS AI)DEI< [THE NAMES OF THE PRINCIPAL INHABITAxnTs OLD ABERDEEN AND WOODSIDE. %httim : WILLIAM BENNETT, PRINTER, 42, Castle Street. 185 : <t A 2 8S. CONTENTS. PAGE. Kalendar for 1855-56 . 5 Agents.for Insurance Companies . 6 Section I.-- Municipal Institutions 9 Establishments 12 ,, II. — Commercial ,, III. — Revenue Department 24 . 42 ,, IV.—Legal Department Department ,, V.—Ecclesiastical 47 „ VI. — Educational Department . 49 „ VII.— Miscellaneous Registration of Births, Death?, and Marri 51 Billeting of Soldiers .... 51: The Northern Club .... Aberdeenshire Horticultural Society . Police Officers, &c Conveyances from Aberdeen Stamp Duties Aberdeen Shipping General Directory of the Inhabitants of the City of Aberd 1 Streets, Squares, Lanes, Courts, &c 124 Trades, Professions, &c 1.97 Cottages, Mansions, and Places in the Suburbs Append ix i Old Aberdeen x Woodside BANK HOLIDAYS. Prince Albert's Birthday, . Aug. 26 New Year's Day, Jan 1 | Friday, Prince of Birthday, Nov. 9 Good April 6 | Wales' Queen's Birthday, . Christmas Day, . Dec. 25 May 24 | Queen's Coronation, June 28 And the Sacramental Fasts. When a Holiday falls on a Sunday, the Monday following is leapt, AGENTS FOR INSURANCE COMPANIES. OFFICES. AGENTS Aberd. Mutual Assurance & Fiieudly Society Alexander Yeats, 47 Schoolhill Do Marine Insurance Association R. Connon, 58 Marischal Street Accidental Death Insurance Co.~~.~~., , A Masson, 4 Queen Street Insurance Age Co,^.^,^.^.—.^,.M, . Alex. Hunter, 61 St. Nicholas Street Agriculturist Cattle Insurance Co.-~,.,„..,,„ . A. -

Gazetteer of Selected Scottish Battlefields

Scotland’s Historic Fields of Conflict Gazetteer: page 1 GAZETTEER OF SELECTED SCOTTISH BATTLEFIELDS LIST OF CONTENTS ABERDEEN II ............................................................................................................. 4 ALFORD ...................................................................................................................... 9 ANCRUM MOOR...................................................................................................... 19 AULDEARN .............................................................................................................. 26 BANNOCKBURN ..................................................................................................... 34 BOTHWELL BRIDGE .............................................................................................. 59 BRUNANBURH ........................................................................................................ 64 DRUMCLOG ............................................................................................................. 66 DUNBAR II................................................................................................................ 71 DUPPLIN MOOR ...................................................................................................... 79 FALKIRK I ................................................................................................................ 87 FALKIRK II .............................................................................................................. -

William Gostling a Walk in and About the City of Canterbury, Second

William Gostling A walk in and about the city of Canterbury, second edition Canterbury 1777 <i> A WALK IN AND ABOUT THE CITY OF CANTERBURY, WITH Many OBSERVATIONS not to be found in any Description hitherto published. THE SECOND EDITION. By WILLIAM GOSTLING, M. A. A NATIVE of the PLACE, AND MINOR CANON of the CATHEDRAL. CANTERBURY; printed by SIMMONS and KIRKBY; MDCCLXXVII. <ii> <blank> <iii> ADVERTISEMENT. THE Subscribers to this second edition may be assured that, although the Author died while his book was in the press, yet the whole was prepared or approved of by him= self, and is printed from his own corrected copy. A few other remarks are contained in the Addenda at the end of the book. The substantial proof of the regard, which his friends retain for the memory of her father, given in a very numerous subscription, calls for the warmest acknowledgements from his daugh= ter; especially as so many have very greatly ex= ceeded the terms of the subscription in their liberality: she hopes they will not be offended by her prefixing an asterisk to such of their names as have come to her knowledge; for she is very sensible of great obligations not only to them, but to many other persons, whose names have not been transmitted to her, and therefore do not appear in her list. Her most grateful thanks are also due to those friends who have contributed to the embellish= ment of this little book; and as the size of the plates would not permit it in them, to express here her sense of his generosity to Francis Grose, <iv> Esq; F. -

He Covenanters of the Merse Their History and Sufferings As Found In

HE COV ENANTERS OF THE MERSE THEIR HISTO RY AND SU FFERING S AS FOU ND IN TH E RECORDS OF V OD TIM} BY THE RE . J O R M A RD N B . G O OWN, . , O PUBL ISHED BY OL IPHANT ANDERSON 8: FERRIER ST MARY STREET mxunvac AND 30 , u, 2 BAI EY 4 L , L ONDON 1 8 9 3 UNIFO RM WITH THIS VOL UME. ’ DR W HYTE S B U NYAN L ECTU RES . Post 800, Antiq ue Laid Papar, Price 23 . 6d. m m u n h ters. B A m D D. of B unya C arac y W , . , ’ hu rch din ur h St George s Free C , E b g . The British Weekly says : We cann ot too warmly welcome this very ' if an d amazin chee re rin t of Dr Wh te s ectures on Bun beaut ul gly p p y l yan . k should t n ce se b thousan ds an d it wi take a The boo a o ll y , ll permanen t B un a t place in y n litera ure. The S ea ker sa s : There is both vi our an d vivacit about th book p y g y e , an d f e in et the ten dern ess is as con s icuou s as the coura e fan cy e l g, y p g ” m f e o x ri c as we an In d d t th t it Is the outco e o m ll w e pe en e ll epen en o ugh . -

U DDLG Papers of the Lloyd-Greame 12Th Cent. - 1950 Family of Sewerby

Hull History Centre: Papers of the Lloyd-Greame Family of Sewerby U DDLG Papers of the Lloyd-Greame 12th cent. - 1950 Family of Sewerby Historical Background: The estate papers in this collection relate to the manor of Sewerby, Bridlington, which was in the hands of the de Sewerdby family from at least the twelfth century until descendants in a female line sold it in 1545. For two decades the estate passed through several hands before being bought by the Carliell family of Bootham, York. The Carliells moved to Sewerby and the four daughters of the first owner, John Carliell, intermarried with local gentry. His son, Tristram Carliell succeeded to the estates in 1579 and upon his death in 1618 he was succeeded by his son, Randolph or Randle Carliell. He died in 1659 and was succeeded by his son, Robert Carliell, who was married to Anne Vickerman, daughter and heiress of Henry Vickerman of Fraisthorpe. Robert Carliell died in in 1685 and his son Henry Carliell was the last male member of the family to live at Sewerby, dying in 1701 (Johnson, Sewerby Hall and Park, pp.4-9). Around 1714 Henry Carliell's heir sold the Sewerby estate to tenants, John and Mary Greame. The Greame family had originated in Scotland before moving south and establishing themselves in and around Bridlington. One line of the family were yeoman farmers in Sewerby, but John Greame's direct family were mariners and merchants in Bridlington. John Greame (b.1664) made two good marriages; first, to Grace Kitchingham, the daughter of a Leeds merchant of some wealth and, second to Mary Taylor of Towthorpe, a co-heiress. -

The Politics and Society of Glasgow, 1648-74 by William Scott Shepherd a Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

The Politics and Society of Glasgow, 1648-74 by William Scott Shepherd A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, to the Faculty of Arts in the University of Glasgow February 1978 ProQuest Number: 13804140 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13804140 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Contents Acknowledgments iii Abbreviations iv Notes on dating and currency vii Abstract viii Introduction to the society of Glasgow: its environment, constitution and institutions. 1 Prelude: the formation of parties in Glasgow, 1645-8 30 PART ONE The struggle for Kirk and King, 1648-52 Chapter 1 The radical ascendancy in Glasgow from October 1648 to the fall of the Western Association in December 1650. 52 Chapter II The time of trial: the revival of malignancy in Glasgow, and the last years of the radical Councils, December 1650 - March 1652. 70 PART TWO Glasgow under the Cromwellian Union, 1652-60 Chapter III A malignant re-assessment: the conservative rule in Glasgow, 1652-5. -

St Andrews Cathedral & St Mary's Church, Kirkheugh

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC035 & PIC038 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM13322) Taken into State care: 1948 (Ownership); 1999 (Ownership) Last reviewed: 2011 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE ST ANDREWS CATHEDRAL & ST MARY’S CHURCH, KIRKHEUGH We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH ST ANDREWS CATHEDRAL & ST MARY'S CHURCH, KIRKHEUGH SYNOPSIS St Andrews cathedral-priory was the premier medieval church in Scotland. In existence since the 8th century as a Celtic monastery, it became a cathedral by the 11th century. -

Scottish Reformation And

Slide 1 Scottish Reformation and Part 2 1 Slide 2 2nd Scottish Reformation Commences • 1637 The reaction - Jenny Geddis • 1637 (25th August) Privy Council decree it’s complusory to purchase Service Book. • 1637 (29th Sept.) Petition sent to PC • 1637 (17th Oct.) PC response • People flood into Edinburgh Dean Hanny - Jenny Geddis • 1637 (15th Nov.) The Four Tables are set up – Nobles, Gentlemen, Burgesses, Ministers 2 Slide 3 The National(23rd July) Covenant • 1638 (20th Feb) ‘The Proclamation’ • 1638 (26th Feb) Covenant renewed – 1580 Covenant – Legal section, comprised laws against Popery – A practical application • Alexander Henderson Alexander Henderson – Born in Fife – Graduated in 1603 St Andrews – Taught philosophy – 1614 Ordained to ministry at Leuchars – Converted under Robert Bruce preaching John 10 – Moderator GA in 1638 • Archibald Johnston of Warriston Johnston of Warriston3 Slide 4 Public Swearing of National Covenant National Covenant Signing at Greyfairs 1638 (19th February/1st March) The National Covenant was signed in Greyfrairs Churchyard. 4 Slide 5 The National Covenant – Its Effect • It reasserted the public’s desire to renounce Roman Catholicism. • It asserted the necessity of the King to rule within the bounds of his authority. • It gave rise to the first free General Assembly for 36 years - held in Glasgow. • Charles 1 raises an army to fight the Scots under General Leslie - Bishop’s Wars 5 Slide 6 The English Dimension • 1640 Long Parliament in England called • 1642 Civil war breaks out in England • 1643 English suggest a military union to the Scots Westminster Assembly of Divines established – 7 Scots. ‘Solemn League and Covenant’ produced by AH • 1646 Charles I surrenders to the Scottish Army 6 Slide 7 Scotland under Cromwell A period of calm and growth • 1649 Charles 1 executed by English Par.