William Gostling a Walk in and About the City of Canterbury, Second

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Soldier Fights for Three Separate but Sometimes Associated Reasons: for Duty, for Payment and for Cause

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stirling Online Research Repository The press and military conflict in early modern Scotland by Alastair J. Mann A soldier fights for three separate but sometimes associated reasons: for duty, for payment and for cause. Nathianiel Hawthorne once said of valour, however, that ‘he is only brave who has affections to fight for’. Those soldiers who are prepared most readily to risk their lives are those driven by political and religious passions. From the advent of printing to the present day the printed word has provided governments and generals with a means to galvanise support and to delineate both the emotional and rational reasons for participation in conflict. Like steel and gunpowder, the press was generally available to all military propagandists in early modern Europe, and so a press war was characteristic of outbreaks of civil war and inter-national war, and thus it was for those conflicts involving the Scottish soldier. Did Scotland’s early modern soldiers carry print into battle? Paul Huhnerfeld, the biographer of the German philosopher and Nazi Martin Heidegger, provides the curious revelation that German soldiers who died at the Russian front in the Second World War were to be found with copies of Heidegger’s popular philosophical works, with all their nihilism and anti-Semitism, in their knapsacks.1 The evidence for such proximity between print and combat is inconclusive for early modern Scotland, at least in any large scale. Officers and military chaplains certainly obtained religious pamphlets during the covenanting period from 1638 to 1651. -

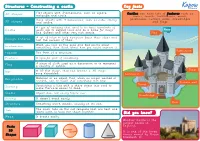

KO DT Y3 Castles

Structures - Constructing a castle Key facts Flat objects with 2-dimensions, such as square, 2D shapes Castles can have lots of features such as rectangle and circle. towers, turrets, battlements, moats, Solid objects with 3-dimensions, such as cube, oblong gatehouses, curtain walls, drawbridges 3D shapes and sphere. and flags. A type of building that used to be built hundreds of Castle years ago to defend land and be a home for Kings and Queens and other very rich people. Flag A set of rules to help designers focus their ideas and Design criteria test the success of them. When you look at the good and bad points about Evaluation something, then think about how you could improve it. Battlement Façade The front of a structure. Feature A specific part of something. Flag A piece of cloth used as a decoration or to represent a country or symbol. Tower Net A 2D flat shape, that can become a 3D shape once assembled. Gatehouse Recyclable Material or an object that, when no longer wanted or needed, can be made into something else new. Curtain wall Turret Scoring Scratching a line with a sharp object into card to make the card easier to bend. Stable Object does not easily topple over. Drawbridge Strong It doesn't break easily. Moat Structure Something which stands, usually on its own. Tab The small tabs on the net template that are bent and glued down to hold the shape together. Did you know? Weak It breaks easily. Windsor Castle is the largest castle in Basic England. -

Some Seventeenth Century Letters and P E T I T I O N S Erom T H E M U N I M E N T S O F T H E Dean a N D C H a P T E R O E C a N T E R B U R Y

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society ( 93 ) SOME SEVENTEENTH CENTURY LETTERS AND P E T I T I O N S EROM T H E M U N I M E N T S O F T H E DEAN A N D C H A P T E R O E C A N T E R B U R Y . EDITED BY 0. EVELEIGH WOODRUFF, M.A. INTRODUCTION THE thirty-two letters and petitions which, by the courtesy of the Dean and Chapter, I have been permitted to trans- cribe, and now to offer to the Kent Archasological Society for pubhcation, were written—with the exception of three or four—in the seventeenth century, on the eve of the troublous times which culminated in the overthrow of Church and King, or in the years immediately fohowing the restoration of the monarchy when deans and chapters, once more in possession of their churches, and estates, were reviving the worship and customs which had been for many years in abeyance. One letter, however, is of earher date than the seventeenth century and three are later. Thus number one is from the pen of Dr. Nicholas Wotton, the first dean of the New Eoundation. Wotton, who was much employed in affairs of state, did not spend much time at Canterbury. His letter, which is dated from London, February 11th, 1564-5, is addressed to his brethren the prebendaries of Canterbury, and its purport is to inform them that Sir Thomas Gresham has offered to build, at his own proper cost and charges, a new Royal Exchange in the city of London. -

The Midwives of Seventeenth-Century London

The Midwives of Seventeenth-Century London DOREEN EVENDEN Mount Saint Vincent University published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb22ru, uk http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, usa http://www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de AlarcoÂn 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain q Doreen Evenden 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2000 Printed in the United States of America bv Typeface Bembo 10/12 pt. System DeskTopPro/ux [ ] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication data Evenden, Doreen. The midwives of seventeenth-century London / Doreen Evenden. p. cm. ± (Cambridge studies in the history of medicine) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-521-66107-2 (hc) 1. Midwives ± England ± London ± History ± 17th century. 2. Obstetrics ± England ± London ± History ± 17th century. 3. Obstetricians ± England ± London ± History ± 17th century. 4. n-uk-en. I. Title. II. Series. rg950.e94 1999 618.2©09421©09032 ± dc21 99-26518 cip isbn 0 521 66107 2 hardback CONTENTS List of Tables and Figures page xiii Acknowledgements xv List of Abbreviations xvii Introduction 1 Early Modern Midwifery Texts 6 The Subjects of the Study 13 Sources and Methodology 17 1 Ecclesiastical Licensing of Midwives 24 Origins of Licensing 25 Oaths and Articles Relating to the Midwife's Of®ce 27 Midwives and the Churching Ritual 31 Acquiring a Licence 34 Midwives at Visitations 42 2 Pre-Licensed Experience 50 Length of Experience 50 Deputy Midwives 54 Matrilineal Midwifery Links 59 Senior Midwives 62 Midwives' Referees 65 Competence vs. -

A Memorial Volume of St. Andrews University In

DUPLICATE FROM THE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY, ST. ANDREWS, SCOTLAND. GIFT OF VOTIVA TABELLA H H H The Coats of Arms belong respectively to Alexander Stewart, natural son James Kennedy, Bishop of St of James IV, Archbishop of St Andrews 1440-1465, founder Andrews 1509-1513, and John Hepburn, Prior of St Andrews of St Salvator's College 1482-1522, cofounders of 1450 St Leonard's College 1512 The University- James Beaton, Archbishop of St Sir George Washington Andrews 1 522-1 539, who com- Baxter, menced the foundation of St grand-nephew and representative Mary's College 1537; Cardinal of Miss Mary Ann Baxter of David Beaton, Archbishop 1539- Balgavies, who founded 1546, who continued his brother's work, and John Hamilton, Arch- University College bishop 1 546-1 57 1, who com- Dundee in pleted the foundation 1880 1553 VOTIVA TABELLA A MEMORIAL VOLUME OF ST ANDREWS UNIVERSITY IN CONNECTION WITH ITS QUINCENTENARY FESTIVAL MDCCCCXI MCCCCXI iLVal Quo fit ut omnis Votiva pateat veluti descripta tabella Vita senis Horace PRINTED FOR THE UNIVERSITY BY ROBERT MACLEHOSE AND COMPANY LIMITED MCMXI GIF [ Presented by the University PREFACE This volume is intended primarily as a book of information about St Andrews University, to be placed in the hands of the distinguished guests who are coming from many lands to take part in our Quincentenary festival. It is accordingly in the main historical. In Part I the story is told of the beginning of the University and of its Colleges. Here it will be seen that the University was the work in the first instance of Churchmen unselfishly devoted to the improvement of their country, and manifesting by their acts that deep interest in education which long, before John Knox was born, lay in the heart of Scotland. -

D'elboux Manuscripts

D’Elboux Manuscripts © B J White, December 2001 Indexed Abstracts page 63 of 156 774. Halsted (59-5-r2c10) • Joseph ASHE of Twickenham, in 1660 • arms. HARRIS under Bradbourne, Sevenoaks • James ASHE of Twickenham, d1733 =, d. Edmund BOWYER of Richmond Park • Joseph WINDHAM = ……, od. James ASHE 775. Halsted (59-5-r2c11) • Thomas BOURCHIER of Canterbury & Halstead, d1486 • Thomas BOURCHIER the younger, kinsman of Thomas • William PETLEY of Halstead, d1528, 2s. Richard = Alyce BOURCHIER, descendant of Thomas BOURCHIER the younger • Thomas HOLT of London, d1761 776. Halsted (59-5-r2c12) • William WINDHAM of Fellbrigge in Norfolk, m1669 (London licence) = Katherine A, d. Joseph ASHE 777. Halsted (59-5-r3c03) • Thomas HOLT of London, d1761, s. Thomas HOLT otp • arms. HOLT of Lancashire • John SARGENT of Halstead Place, d1791 = Rosamund, d1792 • arms. SARGENT of Gloucestershire or Staffordshire, CHAMBER • MAN family of Halstead Place • Henry Stae MAN, d1848 = Caroline Louisa, d1878, d. E FOWLE of Crabtree in Kent • George Arnold ARNOLD = Mary Ann, z1760, d1858 • arms. ROSSCARROCK of Cornwall • John ATKINS = Sarah, d1802 • arms. ADAMS 778. Halsted (59-5-r3c04) • James ASHE of Twickenham, d1733 = ……, d. Edmund BOWYER of Richmond Park • Joseph WINDHAM = ……, od. James ASHE • George Arnold ARNOLD, d1805 • James CAZALET, d1855 = Marianne, d1859, d. George Arnold ARNOLD 779. Ham (57-4-r1c06) • Edward BUNCE otp, z1684, d1750 = Anne, z1701, d1749 • Anne & Jane, ch. Edward & Anne BUNCE • Margaret BUNCE otp, z1691, d1728 • Thomas BUNCE otp, z1651, d1716 = Mary, z1660, d1726 • Thomas FAGG, z1683, d1748 = Lydia • Lydia, z1735, d1737, d. Thomas & Lydia FAGG 780. Ham (57-4-r1c07) • Thomas TURNER • Nicholas CARTER in 1759 781. -

Castle Structure and Function

Vocabulary Castle Structure and Function Name: Date: Castle Use A Castle’s Structure: · Large and of great defensive strength · Surrounded by a wall with a fighting platform · Usually has a large, strong tower A Castle’s Function: · Fortress and military protection · Center of local government · Home of the owner, usually a king The Parts of a Castle allure: the walkway at the top of a castle wall. The allure was often shielded by a protective wall so that guards could move between towers; also called a wall-walk arcading: a series of columns and arches, built in an upside-down U shape arrow loop: a tiny vertical opening in the castle wall; a thin window used for shooting arrows at the enemy; also called a loophole or meurtriere ashlar: blocks of stone, used to build castle wa lls and towers bailey: an open, grassy area inside the walls of the castle containing farm pastures, cottages, and other buildings. Sometimes a castle had more than one bailey; also called a ward. balustrade: railing along a path or stairway barrel vault: semicircular roof made out of wood or stone bastion: a small tower on a courtyard wall or an outside wall battlement: a narrow wall built along the outer edge of the wall-walk to protect soldiers against attack boss: the middle stone in an arch; also called a keystone concentric: having two sets of walls, one inside the other cornerstone: a stone at the corner of a building uniting two intersecting walls, sometimes inscribed with the year the building was constructed; also called a quoin crosswall: a wall inside a large tower Lesson Connection: Castles and Cornerstones Copyright The Kennedy Center. -

Chronological List of the Royal Company of Scottish Archers

CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF THE ROYAL COMPANY OF 2lrrt)er0. Nulla Caledoniam Gens unquarn impune laces set, Usque sagittiferis rohur et ardor inest. Pitcairnii, Poemata. By signing the Laws of the Royal Company of Scottish Archers, you en¬ gage to he faithful to your King and your Country ; for we are not a private company, as some people imagine, but constituted hy Royal Charter his Ma¬ jesty's First Regiment of Guards in Scotland; and if the King should ever come to Edinburgh, it is our duty to take charge of his Royal Person, from Inchbunkland Brae on the east, to Cramond Bridge on the west. But besides being the Body Guards of the King, this Company is the only thing now remaining in Scotland, which properly commemorates the many noble deeds performed by our ancestors by the aid of the Bow. It ought therefore to be the pride and ambition of every true Scotsman to be a member of it. Roslin’s Speech. EDINBURGH: PRINTED BY P. NEII.T.. 1819. PREFACE, T he first part of the following List, is not preserved in the handwriting of the Members themselves, and is not accurate with respect to dates; but the names are copied from the oldest Minute-books of the Company which have been preserved. The list from the 13th of May 1714, is copied from the Parchment Roll, which every Member subscribes with his own hand, in presence of the Council of the Company, when he receives his Diploma. Edinburgh, 1 5th July 1819* | f I LIST OF MEMBERS ADMITTED INTO THE ROYAL COMPANY OF SCOTTISH ARCHERS, FROM 1676, Extracted from Minute-books prior to the 13th of May 1714. -

The Apostolic Succession of the Right Rev. James Michael St. George

The Apostolic Succession of The Right Rev. James Michael St. George © Copyright 2014-2015, The International Old Catholic Churches, Inc. 1 Table of Contents Certificates ....................................................................................................................................................4 ......................................................................................................................................................................5 Photos ...........................................................................................................................................................6 Lines of Succession........................................................................................................................................7 Succession from the Chaldean Catholic Church .......................................................................................7 Succession from the Syrian-Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch..............................................................10 The Coptic Orthodox Succession ............................................................................................................16 Succession from the Russian Orthodox Church......................................................................................20 Succession from the Melkite-Greek Patriarchate of Antioch and all East..............................................27 Duarte Costa Succession – Roman Catholic Succession .........................................................................34 -

Trophy of the Edinburgh Society of Bowlers George R Dalgleish*

Proc SocAntiq Scot, 120 (1990), 189-200, The 'Silver Jack' trophy of the Edinburgh Society of Bowlers George R Dalgleish* '. doucer folk wysing a-jee The by as bowls on Tamson's green.' Allan Ramsay ABSTRACT This paper presents descriptiona 18th-century ofan sporting trophy investigatesand historythe of the society to which it was presented. INTRODUCTION In April 1986, the National Museums of Scotland bought, from a silver dealer in London, a unique 18th-century bowling trophy. Known as the 'Silver Jack', it was originally presented as an annual trophy to the Edinburgh Society of Bowlers in 1771 (NMS registration MEQ1594). The year before the Museums acquired it, it had appeared in an auction of Important English and Continental Silver hel Christie'y dYorb w kNe n (Christie'i s s 1985 t 1167),lo . Enquiries int histore os th it f yo previous ownership have, unfortunately, proved inconclusive, although it does seem it was in the possession of a London collector some time prior to its export to America. Despit e lac th f elateko r provenanc e extremel e 'Jackar th e r w ' fo e y fortunat o havet e considerable contemporary evidenc originas it r efo l presentatio e Societth r whico fo yt d t nhan i relates. This article will presen detailea t d descriptio trophe th thed f no y an n investigat historys eit , settin t withigi contexna histore spore th th f Edinburgto n f i tyo Scotlandd han . DESCRIPTION (illus 1) trophe Th y comprise silvesa r bowl morr ,o e accurately 'jack',a flattenef ,o d spherical form9 ,7 mm in diameter by 67 mm in width. -

Archeological Findings of the Battle of Apache Pass, Fort Bowie National Historic Site Non-Sensitive Version

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Resource Stewardship and Science Archeological Findings of the Battle of Apache Pass, Fort Bowie National Historic Site Non-Sensitive Version Natural Resource Report NPS/FOBO/NRR—2016/1361 ON THIS PAGE Photograph (looking southeast) of Section K, Southeast First Fort Hill, where many cannonball fragments were recorded. Photograph courtesy National Park Service. ON THE COVER Top photograph, taken by William Bell, shows Apache Pass and the battle site in 1867 (courtesy of William A. Bell Photographs Collection, #10027488, History Colorado). Center photograph shows the breastworks as digitized from close range photogrammatic orthophoto (courtesy NPS SOAR Office). Lower photograph shows intact cannonball found in Section A. Photograph courtesy National Park Service. Archeological Findings of the Battle of Apache Pass, Fort Bowie National Historic Site Non-sensitive Version Natural Resource Report NPS/FOBO/NRR—2016/1361 Larry Ludwig National Park Service Fort Bowie National Historic Site 3327 Old Fort Bowie Road Bowie, AZ 85605 December 2016 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. -

Lisa L. Ford Phd Thesis

CONCILIAR POLITICS AND ADMINISTRATION IN THE REIGN OF HENRY VII Lisa L. Ford A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2001 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/7121 This item is protected by original copyright Conciliar Politics and Administration in the Reign of Henry VII Lisa L. Ford A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of St. Andrews April 2001 DECLARATIONS (i) I, Lisa Lynn Ford, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 100,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. Signature of candidate' (ii) I was admitted as a reseach student in January 1996 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph.D. in January 1997; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St. Andrews between 1996 and 2001. / 1 Date: ') -:::S;{:}'(j. )fJ1;;/ Signature of candidate: 1/ - / i (iii) I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of Ph.D. in the University of St. Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. Date \ (If (Ls-> 1 Signature of supervisor: (iv) In submitting this thesis to the University of St.