Negotiating Religious Change Final Version.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

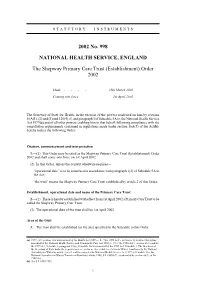

Queen's Printer Version

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2002 No. 998 NATIONAL HEALTH SERVICE, ENGLAND The Shepway Primary Care Trust (Establishment) Order 2002 Made ---- 25th March 2002 Coming into force 1st April 2002 The Secretary of State for Health, in the exercise of the powers conferred on him by sections 16A(1), (2) and (3) and 126(4) of, and paragraph 1 of Schedule 5A to, the National Health Service Act 1977(a) and of all other powers enabling him in that behalf, following compliance with the consultation requirements contained in regulations made under section 16A(5) of the Act(b), hereby makes the following Order: Citation, commencement and interpretation 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the Shepway Primary Care Trust (Establishment) Order 2002 and shall come into force on 1st April 2002. (2) In this Order, unless the context otherwise requires— “operational date” is to be construed in accordance with paragraph 1(2) of Schedule 5A to the Act; “the trust” means the Shepway Primary Care Trust established by article 2 of this Order. Establishment, operational date and name of the Primary Care Trust 2.—(1) There is hereby established with effect from 1st April 2002 a Primary Care Trust to be called the Shepway Primary Care Trust. (2) The operational date of the trust shall be 1st April 2002. Area of the trust 3. The trust shall be established for the area specified in the Schedule to this Order. (a) 1977 c.49; section 16A was inserted by the Health Act 1999 (c. 8) (“the 1999 Act”), section 2(1); section 126(4) was amended by the National Health Service and Community Care Act 1990 (c. -

Letter C Introduction This Index Covers Volumes 110–112 and 114–120 Inclusive (1992–2000) of Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 113 Being the Preceding General Index

Archaeologia Cantiana - On-line Index 2012 GENERAL INDEX TO VOLUMES CX 1992 ( 110 ) to CXX 2000 ( 120 ) Letter C Introduction This index covers volumes 110–112 and 114–120 inclusive (1992–2000) of Archaeologia Cantiana, volume 113 being the preceding General Index. It includes all significant persons, places and subjects with the exception of books reviewed. Volume numbers are shown in bold type and illustrations are denoted by page numbers in italic type or by (illus.) where figures occur throughout the text. The letter n after a page number indicates that the reference will be found in a footnote and pull-out pages are referred to as f – facing. Alphabetisation is word by word. Women are indexed by their maiden name, where known, with cross references from any married name(s). All places within historic Kent are included and are arranged by civil parish. Places that fall within Greater London are to be found listed under their London Borough. Places outside Kent that play a significant part in the text are followed by their post 1974 county. Place names with two elements (e.g. East Peckham, Upper Hardres) will be found indexed under their full place name. T. G. LAWSON, Honorary Editor Kent Archaeological Society, February 2012 Abbreviations m. married Ald. Alderman E. Sussex East Sussex M.P. Member of Parliament b. born ed./eds. editor/editors Notts. Nottinghamshire B. & N.E.S. Bath and North East f facing Oxon. Oxfordshire Somerset fl. floruit P.M. Prime Minister Berks. Berkshire G. London Greater London Pembs. Pembrokeshire Bt. Baronet Gen. General Revd Reverend Bucks. -

Our Grimston Rectors by Stephanie Hall © 2021

Our Grimston Rectors By Stephanie Hall © 2021 Contents Page Our Medieval Rectors ............................................................................................................................. 2 Rev Thomas Hare .................................................................................................................................... 5 Rev Nicholas Carr- died 1530 .................................................................................................................. 6 Rev Richard (or Edward) Rochester died in 1560 ................................................................................... 7 Rev Rochester , 1530 – 1560 ................................................................................................................... 8 Rev William Pordage (Porridge) - died 1585 .......................................................................................... 9 Reverend William Thorowgood , 1544 – 1625 ..................................................................................... 10 Reverend Thomas Thorowgood, 1588 -1669........................................................................................ 12 Rev John Brockett 1613-1664 ............................................................................................................... 14 Reverend Thomas Cremer 1635 - 1694 ................................................................................................ 16 Reverend John Cremer 1663 - 1743 .................................................................................................... -

Monks Horton Parish Meeting From

Monks Horton Parish Meeting from . Councillor, Vice Chairman SUBMISSION TO CSR. FHDC. JULY 2020. This document, published some 18 months ago has been reviewed to account for weather conditions over the past year. POTABLE WATER SUPPLY. I would begin by prefacing this document with a brief description of where we are now in terms of water scarcity and potable water supply for a growing community. The South East of England has always been, in relation to the rest of the UK, water stressed. With a growing local population, certainly over the past 30 years, measures have been taken to try to limit water usage which has, for the most part, been successful. Metering has played a big part in the water intake of households, made compulsory by the designation of our local water company, Affinity Water, of having ‘Water Scarcity Status’. Some 90% of supplies are now metered. Over recent years we have seen drought measures instigated by way of hose pipe bans, car washing facilities restricted or shut down and so forth. Affinity Water has persuaded us to use hippo bags in WC Cisterns, and even today are promoting (FOC) water saving shower heads and similar products to save water. There was even a plan to import water through the channel tunnel fire hydrant system and tow water filled barges across the North from Scandinavia in the mid nineties given the local drought situation. The scenario of severe drought has not yet fully been experienced, but with a growing local population, would the attempted measures of resilience being mooted be enough to alleviate and reduce such a situation happening in the near future? Migration from cities is definitely not one of them and would only serve to exacerbate the water scarcity situation even further. -

Care Services Directory2019/20

Kent Care Services Directory 2019/20 The essential guide to choosing and paying for care and support In association with www.carechoices.co.uk Contents Introduction 4 Important information 56 How to use this Directory Further help and information The local authority’s role 5 Residential care in Kent 60 A message from Kent County Council Comprehensive listings by region Kent Integrated Care Alliance 7 Useful local contacts 115 Helping to shape health and social care Useful national contacts 117 Helping you to stay independent 7 Local services, equipment and solutions Index 118 Support from the council 12 Specialist indices 127 First steps and assessment Essential checklists Services for carers 15 Assistive technology 9 Assessment, benefits and guidance Home care agency 23 Care homes 49 Care and support in the home 17 Residential dementia care 51 How it can help Living with dementia at home 19 Family support, respite and services Paying for care in your home 21 Understanding your options Home care providers 25 A comprehensive list of local agencies Housing with care 42 The different models available Specialist services 43 Disability care, end of life care and advocacy Care homes 47 All the listings in this publication of care homes, care homes with nursing and home care providers Types of homes and activities explained are supplied by the Care Quality Commission Paying for care 53 (CQC) and Care Choices Ltd cannot be held liable for any errors or omissions. Understanding the system To obtain extra copies of this Directory, free of charge, call Care Choices on 01223 207770. -

Some Seventeenth Century Letters and P E T I T I O N S Erom T H E M U N I M E N T S O F T H E Dean a N D C H a P T E R O E C a N T E R B U R Y

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society ( 93 ) SOME SEVENTEENTH CENTURY LETTERS AND P E T I T I O N S EROM T H E M U N I M E N T S O F T H E DEAN A N D C H A P T E R O E C A N T E R B U R Y . EDITED BY 0. EVELEIGH WOODRUFF, M.A. INTRODUCTION THE thirty-two letters and petitions which, by the courtesy of the Dean and Chapter, I have been permitted to trans- cribe, and now to offer to the Kent Archasological Society for pubhcation, were written—with the exception of three or four—in the seventeenth century, on the eve of the troublous times which culminated in the overthrow of Church and King, or in the years immediately fohowing the restoration of the monarchy when deans and chapters, once more in possession of their churches, and estates, were reviving the worship and customs which had been for many years in abeyance. One letter, however, is of earher date than the seventeenth century and three are later. Thus number one is from the pen of Dr. Nicholas Wotton, the first dean of the New Eoundation. Wotton, who was much employed in affairs of state, did not spend much time at Canterbury. His letter, which is dated from London, February 11th, 1564-5, is addressed to his brethren the prebendaries of Canterbury, and its purport is to inform them that Sir Thomas Gresham has offered to build, at his own proper cost and charges, a new Royal Exchange in the city of London. -

Kent Archæological Society Library

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society KENT ARCILEOLOGICAL SOCIETY LIBRARY SIXTH INSTALMENT HUSSEY MS. NOTES THE MS. notes made by Arthur Hussey were given to the Society after his death in 1941. An index exists in the library, almost certainly made by the late B. W. Swithinbank. This is printed as it stands. The number given is that of the bundle or box. D.B.K. F = Family. Acol, see Woodchurch-in-Thanet. Benenden, 12; see also Petham. Ady F, see Eddye. Bethersden, 2; see also Charing Deanery. Alcock F, 11. Betteshanger, 1; see also Kent: Non- Aldington near Lympne, 1. jurors. Aldington near Thurnham, 10. Biddend.en, 10; see also Charing Allcham, 1. Deanery. Appledore, 6; see also Kent: Hermitages. Bigge F, 17. Apulderfield in Cudham, 8. Bigod F, 11. Apulderfield F, 4; see also Whitfield and Bilsington, 7; see also Belgar. Cudham. Birchington, 7; see also Kent: Chantries Ash-next-Fawkham, see Kent: Holy and Woodchurch-in-Thanet. Wells. Bishopsbourne, 2. Ash-next-Sandwich, 7. Blackmanstone, 9. Ashford, 9. Bobbing, 11. at Lese F, 12. Bockingfold, see Brenchley. Aucher F, 4; see also Mottinden. Boleyn F, see Hever. Austen F (Austyn, Astyn), 13; see also Bonnington, 3; see also Goodneston- St. Peter's in Tha,net. next-Wingham and Kent: Chantries. Axon F, 13. Bonner F (Bonnar), 10. Aylesford, 11. Boorman F, 13. Borden, 11. BacIlesmere F, 7; see also Chartham. Boreman F, see Boorman. Baclmangore, see Apulderfield F. Boughton Aluph, see Soalcham. Ballard F, see Chartham. -

Norfolk. Bishopric. Sonmdn: Yarii'outh Lynn Tmn'rl'oimfl

11 0RF0LK LISTS W 1 Q THE PRESENT TIME; ‘ . n uu lj, of wuum JRTRAITS BLISHED, vE L l s T 0 F ' V INCIAL HALFPENNIES ' - R N ORFOLK LIS TS FROM THE REFORMATION To THE PRESENT TIME ; COMPRIS ING Ll" OP L ORD LIEUTEN ANT BARONET S , S , HIG HERIFF H S S , E B ER O F P A R L IA EN T M M S M , 0 ! THE COUNTY of N ORFOLK ; BIS HOPS DEA S CHA CELLORS ARCHDEAC S , N , N , ON , PREBE DA I N R ES , MEMBERS F PARLIAME T O N , MAYORS SHERIFFS RECORDERS STEWARDS , , , , 0 ? THE CITY OF N ORWIC H ; MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT AND MAYORS 0 ? THE BOROUGHS OP MOUTH LYN N T T R YAR , , HE FO D, AN D C ASTL E RIS IN G f Persons connected with th e Coun Also a List o ty, of whom ENGRAVED PORTRAITS I HAV E B EEN PUBL SHED, A N D A D B S C R I P 'I‘ I V E L I S T O F TRADES MENS ’ TOKIBNS PROV INCIAL HA LFPENNIES ISS UED I” THE Y COUNT OF NORFOLK . + 9 NORWICH ‘ V ' PRINTED BY HATCHB IT, STE ENSON , AN D MATCHB", HARKBT PLACI. I NDEX . Lord Lieutenants ' High Sherifl s Members f or the County Nonw xcH o o o o o o o 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Prebendaries Members f or th e City Ym ou'rn Mayors LYNN Members of Parliament Mayors Membersof Parliament CASTLERISING Members of Parliament Engraved Portraits ’ Tradesmans Tok ens ProvincialHalf pennles County and B orough Members elected in 1 837 L O RD L I EUT EN A N T S NORFOLK) “ ' L r Ratcli e Ea rl of us e h re d Hen y fl n S s x , e si ed at Attle borou h uc eded to th e Ea r d m1 1 g , s ce l o 542 , ch . -

I 'A MAN MOSTE MEETE': a NATIONWIDE SURVEY OF

'A MAN MOSTE MEETE': A NATIONWIDE SURVEY OF JUSTICES OF THE PEACE IN MID-TUDOR ENGLAND, 1547-1582 _____________ A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _____________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _____________ By Clarissa Elisabeth Hinojosa May 2014 i 'A MAN MOSTE MEETE': A NATIONWIDE SURVEY OF JUSTICES OF THE PEACE IN MID-TUDOR ENGLAND, 1547-1582 _____________ An Abstract of a Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _____________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _____________ By Clarissa Elisabeth Hinojosa May 2014 ii ABSTRACT This dissertation is a national study of English justices of the peace (JPs) in the mid- Tudor era. It incorporates comparable data from the reigns of Edward VI, Mary I, and the Elizabeth I. Much of the analysis is quantitative in nature: chapters compare the appointments of justices of the peace during the reigns of Edward VI, Mary I, and Elizabeth I, and reveal that purges of the commissions of the peace were far more common than is generally believed. Furthermore, purges appear to have been religiously- based, especially during the reign of Elizabeth I. There is a gap in the quantitative data beginning in 1569, only eleven years into Elizabeth I’s reign, which continues until 1584. In an effort to compensate for the loss of quantitative data, this dissertation analyzes a different primary source, William Lambarde’s guidebook for JPs, Eirenarcha. The fourth chapter makes particular use of Eirenarcha, exploring required duties both in and out of session, what technical and personal qualities were expected of JPs, and how well they lived up to them. -

KENT. Canterbt'ry, 135

'DIRECTORY.] KENT. CANTERBt'RY, 135 I FIRE BRIGADES. Thornton M.R.O.S.Eng. medical officer; E. W. Bald... win, clerk & storekeeper; William Kitchen, chief wardr City; head quarters, Police station, Westgate; four lad Inland Revilnue Offices, 28 High street; John lJuncan, ders with ropes, 1,000 feet of hose; 2 hose carts & ] collector; Henry J. E. Uarcia, surveyor; Arthur Robert; escape; Supt. John W. Farmery, chief of the amal gamated brigades, captain; number of men, q. Palmer, principal clerk; Stanley Groom, Robert L. W. Cooper & Charles Herbert Belbin, clerk.s; supervisors' County (formed in 1867); head quarters, 35 St. George'l; street; fire station, Rose lane; Oapt. W. G. Pidduck, office, 3a, Stour stroot; Prederick Charles Alexander, supervisor; James Higgins, officer 2 lieutenants, an engineer & 7 men. The engine is a Kent &; Canterbury Institute for Trained Nur,ses, 62 Bur Merryweather "Paxton 11 manual, & was, with all tht' gate street, W. H. Horsley esq. hon. sec.; Miss C.!". necessary appliances, supplied to th9 brigade by th, Shaw, lady superintendent directors of the County Fire Office Kent & Canterbury Hospital, Longport street, H. .A.. Kent; head quarters, 29 Westgate; engine house, Palace Gogarty M.D. physician; James Reid F.R.C.S.Eng. street, Acting Capt. Leonard Ashenden, 2 lieutenant~ T. & Frank Wacher M.R.C.S.Eng. cOJ1J8ulting surgeons; &; 6 men; appliances, I steam engine, I manual, 2 hQ5l Thomas Whitehead Reid M.RC.S.Eng. John Greasley Teel!! & 2,500 feet of hose M.RC.S.Eng. Sidney Wacher F.R.C.S.Eng. & Z. Fren Fire Escape; the City fire escape is kept at the police tice M.R.C.S. -

D'elboux Manuscripts

D’Elboux Manuscripts © B J White, December 2001 Indexed Abstracts page 63 of 156 774. Halsted (59-5-r2c10) • Joseph ASHE of Twickenham, in 1660 • arms. HARRIS under Bradbourne, Sevenoaks • James ASHE of Twickenham, d1733 =, d. Edmund BOWYER of Richmond Park • Joseph WINDHAM = ……, od. James ASHE 775. Halsted (59-5-r2c11) • Thomas BOURCHIER of Canterbury & Halstead, d1486 • Thomas BOURCHIER the younger, kinsman of Thomas • William PETLEY of Halstead, d1528, 2s. Richard = Alyce BOURCHIER, descendant of Thomas BOURCHIER the younger • Thomas HOLT of London, d1761 776. Halsted (59-5-r2c12) • William WINDHAM of Fellbrigge in Norfolk, m1669 (London licence) = Katherine A, d. Joseph ASHE 777. Halsted (59-5-r3c03) • Thomas HOLT of London, d1761, s. Thomas HOLT otp • arms. HOLT of Lancashire • John SARGENT of Halstead Place, d1791 = Rosamund, d1792 • arms. SARGENT of Gloucestershire or Staffordshire, CHAMBER • MAN family of Halstead Place • Henry Stae MAN, d1848 = Caroline Louisa, d1878, d. E FOWLE of Crabtree in Kent • George Arnold ARNOLD = Mary Ann, z1760, d1858 • arms. ROSSCARROCK of Cornwall • John ATKINS = Sarah, d1802 • arms. ADAMS 778. Halsted (59-5-r3c04) • James ASHE of Twickenham, d1733 = ……, d. Edmund BOWYER of Richmond Park • Joseph WINDHAM = ……, od. James ASHE • George Arnold ARNOLD, d1805 • James CAZALET, d1855 = Marianne, d1859, d. George Arnold ARNOLD 779. Ham (57-4-r1c06) • Edward BUNCE otp, z1684, d1750 = Anne, z1701, d1749 • Anne & Jane, ch. Edward & Anne BUNCE • Margaret BUNCE otp, z1691, d1728 • Thomas BUNCE otp, z1651, d1716 = Mary, z1660, d1726 • Thomas FAGG, z1683, d1748 = Lydia • Lydia, z1735, d1737, d. Thomas & Lydia FAGG 780. Ham (57-4-r1c07) • Thomas TURNER • Nicholas CARTER in 1759 781. -

Some Problems of the North Downs Trackway in Kent

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society SOME PROBLEMS OF THE NORTH DOWNS TRACKWAY IN KENT By REV. H. W. R. Liman, S.J., M.A.(0xon.) THE importance of this pre-historic route from the Continent to the ancient habitat of man in Wiltshire has long been recognized. In the Surrey Archceological Collections of 1964 will be found an attempted re-appraisal of its route through the county of Surrey. Although the problems connected with its passage through Kent are fewer owing to its being better preserved, there are some points which I think still deserve attention—the three river crossings of the Darenth, the Medway and the Stour; the crossing of the Elham valley; and the passage to Canterbury of the branch route from Eastwell Park, known as the Pilgrims' Way. It may be worth while, before dealing with the actual crossings, to note a few general characteristics. Mr. I. D. Margary—our most eminent authority on ancient roads in Britain—has pointed out the dual nature of this trackway. It com- prises a Ridgeway and a Terraceway. The first runs along the crest of the escarpment. The second runs parallel to it, usually at the point below the escarpment where the slope flattens out into cultivation. In Kent for the most part the Terraceway has survived more effectually than the Ridgeway. It is for much of its length used as a modern road, marked by the familiar sign 'Pilgrims' Way'. Except at its eastern terminus the Ridgeway has not been so lucky, although it can be traced fairly accurately by those who take the trouble to do so.