Fortification in the XVI Century: the Case of Famagusta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Northgate Reconstruction

131 7 THE NORTHGATE RECONSTRUCTION P Holder and J Walker INTRODUCTION have come from the supposedly ancient quarries at Collyhurst some few kilometres north-east of the The Unit was asked to provide advice and fort. As this source was not available, Hollington assistance to Manchester City Council so that the Red Sandstone from Staffordshire was used to form City could reconstruct the Roman fort wall and a wall of coursed facing blocks 200-320 mm long by defences at Manchester as they would have appeared 140-250 mm deep by 100-120 mm thick. York stone around the beginning of the 3rd century (Phase 4). was used for paving, steps and copings. A recipe for the right type of mortar, which consisted of This short report has been included in the volume three parts river sand, three parts building sand, in order that a record of the archaeological work two parts lime and one part white cement, was should be available for visitors to the site. obtained from Hampshire County Council. The Ditches and Roods The Wall and Rampart The Phase 4a (see Chapter 4, Area B) ditches were Only the foundations and part of the first course re-establised along their original line to form a of the wall survived (see Chapter 4, Phase 4, Area defensive circuit consisting of an outer V-shaped A). The underlying foundations consisted of ditch in front of a smaller inner ditch running interleaved layers of rammed clay and river close to the fort wall. cobble. On top of the foundations of the fort wall lay traces of a chamfered plinth (see Chapter 5g) There were three original roads; the main road made up of large red sandstone blocks, behind from the Northgate that ran up to Deansgate, the which was a rough rubble backing. -

New Methodologies for the Documentation of Fortified Architecture in the State of Ruins

The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XLII-5/W1, 2017 GEOMATICS & RESTORATION – Conservation of Cultural Heritage in the Digital Era, 22–24 May 2017, Florence, Italy NEW METHODOLOGIES FOR THE DOCUMENTATION OF FORTIFIED ARCHITECTURE IN THE STATE OF RUINS F. Fallavollita a, A. Ugolini a a Dept. of Architecture, University of Bologna, Viale del Risorgimento, 2, 40136 Bologna, Italy - (federico.fallavollita, andrea.ugolini)@unibo.it KEY WORDS: Castles, Laser Scanner, Digital Photogrammetry, Architectural Survey, Restoration ABSTRACT: Fortresses and castles are important symbols of social and cultural identity providing tangible evidence of cultural unity in Europe. They are items for which it is always difficult to outline a credible prospect of reuse, their old raison d'être- namely the military, political and economic purposes for which they were built- having been lost. In recent years a Research Unit of the University of Bologna composed of architects from different disciplines has conducted a series of studies on fortified heritage in the Emilia Romagna region (and not only) often characterized by buildings in ruins. The purpose of this study is mainly to document a legacy, which has already been studied in depth by historians, and previously lacked reliable architectural surveys for the definition of a credible as well as sustainable conservation project. Our contribution will focus on different techniques and methods used for the survey of these architectures, the characteristics of which- in the past- have made an effective survey of these buildings difficult, if not impossible. The survey of a ruin requires, much more than the evaluation of an intact building, reading skills and an interpretation of architectural spaces to better manage the stages of documentation and data processing. -

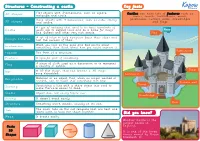

KO DT Y3 Castles

Structures - Constructing a castle Key facts Flat objects with 2-dimensions, such as square, 2D shapes Castles can have lots of features such as rectangle and circle. towers, turrets, battlements, moats, Solid objects with 3-dimensions, such as cube, oblong gatehouses, curtain walls, drawbridges 3D shapes and sphere. and flags. A type of building that used to be built hundreds of Castle years ago to defend land and be a home for Kings and Queens and other very rich people. Flag A set of rules to help designers focus their ideas and Design criteria test the success of them. When you look at the good and bad points about Evaluation something, then think about how you could improve it. Battlement Façade The front of a structure. Feature A specific part of something. Flag A piece of cloth used as a decoration or to represent a country or symbol. Tower Net A 2D flat shape, that can become a 3D shape once assembled. Gatehouse Recyclable Material or an object that, when no longer wanted or needed, can be made into something else new. Curtain wall Turret Scoring Scratching a line with a sharp object into card to make the card easier to bend. Stable Object does not easily topple over. Drawbridge Strong It doesn't break easily. Moat Structure Something which stands, usually on its own. Tab The small tabs on the net template that are bent and glued down to hold the shape together. Did you know? Weak It breaks easily. Windsor Castle is the largest castle in Basic England. -

CPCCST3003A Split Stone Manually

CPCCST3003A Split stone manually Release: 1 CPCCST3003A Split stone manually Date this document was generated: 26 May 2012 CPCCST3003A Split stone manually Modification History Not Applicable Unit Descriptor Unit descriptor This unit specifies the outcomes required to split stone using a range of methods for both hard and soft stone. Application of the Unit Application of the unit This unit of competency supports the achievement of skills and knowledge to split stone manually, which may include working with others and as a member of a team. Licensing/Regulatory Information Not Applicable Pre-Requisites Prerequisite units CPCCOHS2001A Apply OHS requirements, policies and procedures in the construction industry Approved Page 2 of 11 © Commonwealth of Australia, 2012 Construction & Property Services Industry Skills Council CPCCST3003A Split stone manually Date this document was generated: 26 May 2012 Employability Skills Information Employability skills This unit contains employability skills. Elements and Performance Criteria Pre-Content Elements describe the Performance criteria describe the performance needed to essential outcomes of a demonstrate achievement of the element. Where bold unit of competency. italicised text is used, further information is detailed in the required skills and knowledge section and the range statement. Assessment of performance is to be consistent with the evidence guide. Approved Page 3 of 11 © Commonwealth of Australia, 2012 Construction & Property Services Industry Skills Council CPCCST3003A Split stone manually Date this document was generated: 26 May 2012 Elements and Performance Criteria ELEMENT PERFORMANCE CRITERIA 1. Plan and prepare. 1.1. Work instructions and operational details are obtained using relevant information, confirmed and applied for planning and preparation purposes. -

Roodstown Castle Video Script

Roodstown Castle Adèle Commins and Daithí Kearney Roodstown Castle is a prominent feature of the built heritage of Co. Louth. Its excellent state of preservation gives it added stature and it provides an excellent example of a tower house in Ireland. National records provide an interesting account of the change of name of the townland of Roodstown since 1301. Over the years the following variants of the name existed: Rotheston (1301), Routheston (1305), Rotheston (1582), Roothstowne (1635), Roothtowne (1655), Roothestowne (1658), Roods towne (1659), Rootstowne (1664), Roodestowne (1666), Roodstowne (1667), Roothstowne (1670), Roothtown (1685), Rootstown (1777), Roodstown (1836). At this time it was noted that Rooth was a family name.1 The 1837 Topographical Dictionary of Ireland noted that the townland contained 25 houses at the time with 148 inhabitants and described it as a village.2 This dictionary also suggested that the townland was called Rootstown or Ruthstown. In the Barony of Ardee and Civil Parish of Stabannan, the townland of Roodstown is surrounded by a number of other townlands including Gudderstown, Rock, Broadlough, Drumcashel, Philibenstown and Irishtown. Roodstown Castle is the most prominent structure today in the townland. The castle overlooks the N33 and the River Dee and is an imposing feature in the landscape visible today from a number of surrounding roads including the N52 and N33. Roodstown Castle is positioned on the roadside at a junction. To the right of the castle is Ardee and to the left of the castle is Stabannan. In days gone by this was the main road from Ardee to Castlebellingham. -

MHA Newsletter July 2015

MHA Newsletter No. 6/2015 www.mha.org.au July 2015 Merħba! A warm welcome is extended to all our June 2014 members and friends. THE MALTESE HISTORICAL Joe Borg’s lecture about the great Siege on 16 June June 2014 was well attended, and he has sent us a summary of his ASSOCIATION (AUSTRALIA) talk. A link to the PowerPoint and lecture recording are provided in case you missed it. After the lecture, two invites you to attend the new members joined the MHA, Marie Pirotta and John Melbourne launch of the Bonnice. I am sure you will make them feel welcome, with true Maltese hospitality. John contributed the commemorative book: excellent pictorial essay on Fort St Elmo to the last newsletter. Malta and the ANZACS - You may recall that at our last AGM the MHA agreed to Nurse of the Mediterranean help sponsor the publication of Frank Scicluna’s book, Malta and the ANZACS - Nurse of the Mediterranean. It has finally been released. As an individual sponsor, I have already received a copy, which I have reviewed on page 6 of this newsletter. In a word, it is superb! The Maltese Consul General, Mr. Victor Grech, will officially launch the book in Melbourne at our next meeting on 21 July. The author, Frank Scicluna OAM, will be in attendance, speaking about his book and will be bringing copies for sale. It is a public event, so tell everyone you can think of. Malta’s role in World War I makes me particularly proud of my Maltese heritage. Joe Borg’s third lecture on the Great Siege was originally scheduled for this month but will be postponed to September. -

Castle Structure and Function

Vocabulary Castle Structure and Function Name: Date: Castle Use A Castle’s Structure: · Large and of great defensive strength · Surrounded by a wall with a fighting platform · Usually has a large, strong tower A Castle’s Function: · Fortress and military protection · Center of local government · Home of the owner, usually a king The Parts of a Castle allure: the walkway at the top of a castle wall. The allure was often shielded by a protective wall so that guards could move between towers; also called a wall-walk arcading: a series of columns and arches, built in an upside-down U shape arrow loop: a tiny vertical opening in the castle wall; a thin window used for shooting arrows at the enemy; also called a loophole or meurtriere ashlar: blocks of stone, used to build castle wa lls and towers bailey: an open, grassy area inside the walls of the castle containing farm pastures, cottages, and other buildings. Sometimes a castle had more than one bailey; also called a ward. balustrade: railing along a path or stairway barrel vault: semicircular roof made out of wood or stone bastion: a small tower on a courtyard wall or an outside wall battlement: a narrow wall built along the outer edge of the wall-walk to protect soldiers against attack boss: the middle stone in an arch; also called a keystone concentric: having two sets of walls, one inside the other cornerstone: a stone at the corner of a building uniting two intersecting walls, sometimes inscribed with the year the building was constructed; also called a quoin crosswall: a wall inside a large tower Lesson Connection: Castles and Cornerstones Copyright The Kennedy Center. -

ART HISTORY of VENICE HA-590I (Sec

Gentile Bellini, Procession in Saint Mark’s Square, oil on canvas, 1496. Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice ART HISTORY OF VENICE HA-590I (sec. 01– undergraduate; sec. 02– graduate) 3 credits, Summer 2016 Pratt in Venice––Pratt Institute INSTRUCTOR Joseph Kopta, [email protected] (preferred); [email protected] Direct phone in Italy: (+39) 339 16 11 818 Office hours: on-site in Venice immediately before or after class, or by appointment COURSE DESCRIPTION On-site study of mosaics, painting, architecture, and sculpture of Venice is the primary purpose of this course. Classes held on site alternate with lectures and discussions that place material in its art historical context. Students explore Byzantine, Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque examples at many locations that show in one place the rich visual materials of all these periods, as well as materials and works acquired through conquest or collection. Students will carry out visually- and historically-based assignments in Venice. Upon return, undergraduates complete a paper based on site study, and graduate students submit a paper researched in Venice. The Marciana and Querini Stampalia libraries are available to all students, and those doing graduate work also have access to the Cini Foundation Library. Class meetings (refer to calendar) include lectures at the Università Internazionale dell’ Arte (UIA) and on-site visits to churches, architectural landmarks, and museums of Venice. TEXTS • Deborah Howard, Architectural History of Venice, reprint (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2003). [Recommended for purchase prior to departure as this book is generally unavailable in Venice; several copies are available in the Pratt in Venice Library at UIA] • David Chambers and Brian Pullan, with Jennifer Fletcher, eds., Venice: A Documentary History, 1450– 1630 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001). -

Building the Lighthouse on Montague

SELF-GUIDED TOUR 2 BUILDING THE LIGHT This self-guided tour focuses on the construction of the Lighthouse on Montague Island - in particular the work of the stonemasons. PERHAPS BEGIN THIS TOUR SITTING ON THE STEPS LEADING UP TO THE TOWER... LOOK... at the tower: • Observe how it “grows” from the rock... • Appreciate its proportions suggesting strength, durability and watchfulness. • Notice the courses of blocks, the windows, the overhangs, the balcony and the lantern room at the top. CONSIDER... This Lighthouse has been operating continuously since 1881 - staffed until September 1986, and then automatically since 1986. The Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) now maintains the tower and light, totally funded by the shipping and insurance industries. GUIDE TO YOUR TOUR SIGNIFICANT DATES: 1873 Decision for a “First Order, Fixed and Flashing Light” on Montague Island 1877 Monies allocated within NSW budget – James Barnet, Colonial Architect, designs the lighthouse and buildings. 1878 – October Tenders let – Musson and Co wins the tender. 1879 – June? Musson surrenders his contract 1880 – July Fresh tenders called – William H. Jennings of Sydney wins the tender. 1880 – September Visitors impressed with Jennings’ Progress. 1881 – October Work completed by Jennings, 4 months ahead of schedule. 1881 – November 1st Lighthouse is formally opened by the NSW Marine Board THE DESIGN OF THE LIGHT STATION AND TOWER. James Barnet, the Colonial Architect from 1865 to 1890, was responsible for some 15 lighthouses in NSW, in particular during the period 1875-1885. Other lighthouses he designed include the Macquarie Light on Sydney’s south head, after Greenway’s tower experienced problems; Cape Byron; Norah Head; and the nearby Greencape light, south of Eden. -

The Trouble with Bulls: the Cacce Dei Tori in Early4modern Venice

The Trouble with Bulls: The Cacce dei Tori in Early-Modern Venice ROBERT C. DAVIS* The city of Venice has been historiographically identified with festival. Venetians staged regular symbolic enactments of the city’s piety, beauty, unity, military valour, connection with the sea, and sense of justice, usually exploiting Venice’s public squares, boats, bridges, and canals to give these occasions a unique character. One festival, however, the cacce dei tori or baiting of bulls, celebrated none of these virtues and had nothing to do with the sea. Usually found in cities with strong feudal and economic ties to the countryside, such events would seem out of place in a city with no such ties and an impractical environment for large animals. The roots of the cacce dei tori, however, lay more in Venice’s intense neighbourhood and factional rivalries than in urban-rural tensions. Sur le plan historiographique, on identifie la ville de Venise aux festivals. Les Vénitiens faisaient régulièrement des mises en scène symboliques de la piété, de la beauté, de l’unité, de la vaillance militaire, du lieu avec la mer et du sens de la justice de la ville, exploitant habituellement les places publiques, les bateaux, les ponts et les canaux de Venise pour conférer un cachet unique à ces occasions. Un festival, toutefois, le cacce dei tori, ou l’appâtage des taureaux, ne célébrait aucune de ces vertus et n’avait rien à voir avec la mer. De tels événements, qui se dérou- laient normalement dans des villes ayant de solides liens féodaux et économiques avec la campagne, paraîtraient incongrus dans une ville ne présentant aucuns liens de la sorte et offrant un milieu inhospitalier pour des animaux de grande taille. -

Soldier Illness and Environment in the War of 1812

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library Spring 5-8-2020 "The Men Were Sick of the Place" : Soldier Illness and Environment in the War of 1812 Joseph R. Miller University of Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Canadian History Commons, Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Joseph R., ""The Men Were Sick of the Place" : Soldier Illness and Environment in the War of 1812" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3208. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/3208 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “THE MEN WERE SICK OF THE PLACE”: SOLDIER ILLNESS AND ENVIRONMENT IN THE WAR OF 1812 By Joseph R. Miller B.A. North Georgia University, 2003 M.A. University of Maine, 2012 A DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in History) The Graduate School The University of Maine May 2020 Advisory Committee: Scott W. See, Professor Emeritus of History, Co-advisor Jacques Ferland, Associate Professor of History, Co-advisor Liam Riordan, Professor of History Kathryn Shively, Associate Professor of History, Virginia Commonwealth University James Campbell, Professor of Joint, Air War College, Brigadier General (ret) Michael Robbins, Associate Research Professor of Psychology Copyright 2020 Joseph R. -

Archeological Findings of the Battle of Apache Pass, Fort Bowie National Historic Site Non-Sensitive Version

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Resource Stewardship and Science Archeological Findings of the Battle of Apache Pass, Fort Bowie National Historic Site Non-Sensitive Version Natural Resource Report NPS/FOBO/NRR—2016/1361 ON THIS PAGE Photograph (looking southeast) of Section K, Southeast First Fort Hill, where many cannonball fragments were recorded. Photograph courtesy National Park Service. ON THE COVER Top photograph, taken by William Bell, shows Apache Pass and the battle site in 1867 (courtesy of William A. Bell Photographs Collection, #10027488, History Colorado). Center photograph shows the breastworks as digitized from close range photogrammatic orthophoto (courtesy NPS SOAR Office). Lower photograph shows intact cannonball found in Section A. Photograph courtesy National Park Service. Archeological Findings of the Battle of Apache Pass, Fort Bowie National Historic Site Non-sensitive Version Natural Resource Report NPS/FOBO/NRR—2016/1361 Larry Ludwig National Park Service Fort Bowie National Historic Site 3327 Old Fort Bowie Road Bowie, AZ 85605 December 2016 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service.