A Soldier Fights for Three Separate but Sometimes Associated Reasons: for Duty, for Payment and for Cause

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

July at the Museum!

July at the Museum! Battle of Aughrim, John Mulvaney. The Battle of the Boyne, July 1st 1690. On 1 July 1690, the Battle of the Boyne was fought between King James II's Jacobite army, and the Williamite Army under William of Orange. Despite only being a minor military victory in favour of the Williamites, it has a major symbolic significance. The Battle's annual commemorations by The Orange Order, a masonic-style fraternity dedicated to the protection of the Protestant Ascendancy, remain a topic of great controversy. This is especially true in areas of Northern Ireland where sectarian tensions remain rife. No year in Irish history is better known than 1690. No Irish battle is more famous than William III's victory over James II at the River Boyne, a few miles west of Drogheda. James, a Roman Catholic, had lost the throne of England in the bloodless "Glorious Revolution" of 1688. William was Prince of Orange, a Dutch-speaking Protestant married to James's daughter Mary, and became king at the request of parliament. James sought refuge with his old ally, Louis XIV of France, who saw an opportunity to strike at William through Ireland. He provided French officers and arms for James, who landed at Kinsale in March 1689. The lord deputy, the Earl of Tyrconnell was a Catholic loyal to James, and his Irish army controlled most of the island. James quickly summoned a parliament, largely Catholic, which proceeded to repeal the legislation under which Protestant settlers had acquired land. During the rule of Tyrconnell, the first Catholic viceroy since the Reformation, Protestants had seen their influence eroded in the army, in the courts and in civil government. -

Famous Scots Phone Is 425-806-3734

Volume 117 Issue 7 October 2019 https://tickets.thetripledoor.net/eventperformances.asp?e vt=1626. https://skerryvore.com NEXT GATHERING 5 Fred Morrison Concert, Littlefield Celtic Center, 1124 Our October gathering will be on Sunday, Cleveland Ave., Mount Vernon, WA. 7pm. $30. 360-416- October 13th. We are back to our usual second 4934 https://celticarts.org/celtic-events/fred19/ Sunday meeting date. 8 SSHGA Meeting, 7:30 pm. St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church 111 NE 80th St., Seattle, WA. Info: (206) 522- As usual, we will gather at 2:00 pm at Haller 2541 Lake United Methodist Church, 13055 1st Ave. 10 Gaelic Supergroup Daimh Ceilidh, Lake City NE, Seattle, WA. 98125. Eagles, 8201 Lake City Way NE, Seattle. 7pm. $15 Reservations at [email protected] or 206-861- The program will be a presentation by Tyrone 4530. Heade of Elliot Bay Pipes and Drums on his 11 Gaelic Supergroup Daimh Concert, Ballard experiences as a professional piper. Homestead, 6541 Jones Ave. NW, Seattle, 7:30pm. $25. _____________________________________ 12 Gaelic Supergroup Daimh Concert, Littlefield Celtic Center, 1124 Cleveland Ave., Mount Vernon, WA. 7pm. Facebook $25. 360-416-4934 https://celticarts.org/celtic- events/daimh-19/ The Caledonians have a Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/seattlecaledonians/?r 13 Caledonian & St. Andrews Society Gathering, 2:00 pm. Haller Lake United Methodist Church, 13055 1st ef=bookmarks Ave. NE, Seattle, WA. 98125. Diana Smith frequently posts interesting articles http://www.caledonians.com and notices, so check back often. 26 MacToberfest Scotch Ale Competition, Littlefield __________________________________________ Celtic Center, 1124 Cleveland Ave., Mount Vernon, WA. -

"For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh Mackay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 4-2012 "For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh MacKay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland Andrew Phillip Frantz College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Frantz, Andrew Phillip, ""For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh MacKay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland" (2012). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 480. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/480 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF SO GOOD A CAUSE”: HUGH MACKAY, THE HIGHLAND WAR AND THE GLORIOUS REVOLUTION IN SCOTLAND A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors is History from the College of William and Mary in Virginia, by Andrew Phillip Frantz Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) _________________________________________ Nicholas Popper, Director _________________________________________ Paul Mapp _________________________________________ Simon Stow Williamsburg, Virginia April 30, 2012 Contents Figures iii Acknowledgements iv Introduction 1 Chapter I The Origins of the Conflict 13 Chapter II Hugh MacKay and the Glorious Revolution 33 Conclusion 101 Bibliography 105 iii Figures 1. General Hugh MacKay, from The Life of Lieutenant-General Hugh MacKay (1836) 41 2. The Kingdom of Scotland 65 iv Acknowledgements William of Orange would not have been able to succeed in his efforts to claim the British crowns if it were not for thousands of people across all three kingdoms, and beyond, who rallied to his cause. -

Erin and Alban

A READY REFERENCE SKETCH OF ERIN AND ALBAN WITH SOME ANNALS OF A BRANCH OF A WEST HIGHLAND FAMILY SARAH A. McCANDLESS CONTENTS. INTRODUCTION. PART I CHAPTER I PRE-HISTORIC PEOPLE OF BRITAIN 1. The Stone Age--Periods 2. The Bronze Age 3. The Iron Age 4. The Turanians 5. The Aryans and Branches 6. The Celto CHAPTER II FIRST HISTORICAL MENTION OF BRITAIN 1. Greeks 2. Phoenicians 3. Romans CHAPTER III COLONIZATION PE}RIODS OF ERIN, TRADITIONS 1. British 2. Irish: 1. Partholon 2. Nemhidh 3. Firbolg 4. Tuatha de Danan 5. Miledh 6. Creuthnigh 7. Physical CharacteriEtics of the Colonists 8. Period of Ollaimh Fodhla n ·'· Cadroc's Tradition 10. Pictish Tradition CHAPTER IV ERIN FROM THE 5TH TO 15TH CENTURY 1. 5th to 8th, Christianity-Results 2. 9th to 12th, Danish Invasions :0. 12th. Tribes and Families 4. 1169-1175, Anglo-Norman Conquest 5. Condition under Anglo-Norman Rule CHAPTER V LEGENDARY HISTORY OF ALBAN 1. Irish sources 2. Nemedians in Alban 3. Firbolg and Tuatha de Danan 4. Milesians in Alban 5. Creuthnigh in Alban 6. Two Landmarks 7. Three pagan kings of Erin in Alban II CONTENTS CHAPTER VI AUTHENTIC HISTORY BEGINS 1. Battle of Ocha, 478 A. D. 2. Dalaradia, 498 A. D. 3. Connection between Erin and Alban CHAPTER VII ROMAN CAMPAIGNS IN BRITAIN (55 B.C.-410 A.D.) 1. Caesar's Campaigns, 54-55 B.C. 2. Agricola's Campaigns, 78-86 A.D. 3. Hadrian's Campaigns, 120 A.D. 4. Severus' Campaigns, 208 A.D. 5. State of Britain During 150 Years after SeveTus 6. -

Christopher Upton Phd Thesis

?@A374? 7; ?2<@@7?6 81@7; 2IQJRSOPIFQ 1$ APSON 1 @IFRJR ?TCMJSSFE GOQ SIF 3FHQFF OG =I3 BS SIF ANJUFQRJSX OG ?S$ 1NEQFVR '.-+ 5TLL MFSBEBSB GOQ SIJR JSFM JR BUBJLBCLF JN >FRFBQDI0?S1NEQFVR/5TLL@FWS BS/ ISSP/%%QFRFBQDI#QFPORJSOQX$RS#BNEQFVR$BD$TK% =LFBRF TRF SIJR JEFNSJGJFQ SO DJSF OQ LJNK SO SIJR JSFM/ ISSP/%%IEL$IBNELF$NFS%'&&()%(,)* @IJR JSFM JR PQOSFDSFE CX OQJHJNBL DOPXQJHIS STUDIES IN SCOTTISH LATIN by Christopher A. Upton Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of St. Andrews October 1984 ýýFCA ýý£ s'i ý`q. q DRE N.6 - Parentibus meis conjugique meae. Iý Christopher Allan Upton hereby certify that this thesis which is approximately 100,000 words in length has been written by men that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. ý.. 'C) : %6 date .... .... signature of candidat 1404100 I was admitted as a research student under Ordinance No. 12 on I October 1977 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph. D. on I October 1978; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 1977 and 1980. $'ý.... date . .. 0&0.9 0. signature of candidat I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate to the degree of Ph. D. of the University of St Andrews and that he is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

A Memorial Volume of St. Andrews University In

DUPLICATE FROM THE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY, ST. ANDREWS, SCOTLAND. GIFT OF VOTIVA TABELLA H H H The Coats of Arms belong respectively to Alexander Stewart, natural son James Kennedy, Bishop of St of James IV, Archbishop of St Andrews 1440-1465, founder Andrews 1509-1513, and John Hepburn, Prior of St Andrews of St Salvator's College 1482-1522, cofounders of 1450 St Leonard's College 1512 The University- James Beaton, Archbishop of St Sir George Washington Andrews 1 522-1 539, who com- Baxter, menced the foundation of St grand-nephew and representative Mary's College 1537; Cardinal of Miss Mary Ann Baxter of David Beaton, Archbishop 1539- Balgavies, who founded 1546, who continued his brother's work, and John Hamilton, Arch- University College bishop 1 546-1 57 1, who com- Dundee in pleted the foundation 1880 1553 VOTIVA TABELLA A MEMORIAL VOLUME OF ST ANDREWS UNIVERSITY IN CONNECTION WITH ITS QUINCENTENARY FESTIVAL MDCCCCXI MCCCCXI iLVal Quo fit ut omnis Votiva pateat veluti descripta tabella Vita senis Horace PRINTED FOR THE UNIVERSITY BY ROBERT MACLEHOSE AND COMPANY LIMITED MCMXI GIF [ Presented by the University PREFACE This volume is intended primarily as a book of information about St Andrews University, to be placed in the hands of the distinguished guests who are coming from many lands to take part in our Quincentenary festival. It is accordingly in the main historical. In Part I the story is told of the beginning of the University and of its Colleges. Here it will be seen that the University was the work in the first instance of Churchmen unselfishly devoted to the improvement of their country, and manifesting by their acts that deep interest in education which long, before John Knox was born, lay in the heart of Scotland. -

Scotland – North

Scotland – North Scotland was at the heart of Jacobitism. All four Jacobite risings - in 1689-91, 1715-16, 1719 and 1745-46 - took place either entirely (the first and third) or largely (the second and fourth) in Scotland. The north of Scotland was particularly important in the story of the risings. Two of them (in 1689-91 and 1719) took place entirely in the north of Scotland. The other two (in 1715-16 and 1745-46) began and ended in the north of Scotland, although both had wider theatres during the middle stages of the risings. The Jacobite movement in Scotland managed to attract a wide range of support, which is why more than one of the risings came close to succeeding. This support included Lowlanders as well as Highlanders, Episcopalians as well as Catholics (not to mention some Presbyterians and others), women as well as men, and an array of social groups and ages. This Scotland-North section has many Jacobite highlights. These include outstanding Jacobite collections in private houses such as Blair Castle, Scone Palace and Glamis Castle; state-owned houses with Jacobite links, such as Drum Castle and Corgarff Castle; and museums and exhibitions such as the West Highland Museum and the Culloden Visitor Centre. They also include places which played a vital role in Jacobite history, such as Glenfinnan, and the loyal Jacobite ports of the north-east, and battlefields (six of the land battles fought during the risings are in this section, together with several other skirmishes on land and sea). The decision has been made here to divide the Scottish sections into Scotland – South and Scotland – North, rather than the more traditional Highlands and Lowlands. -

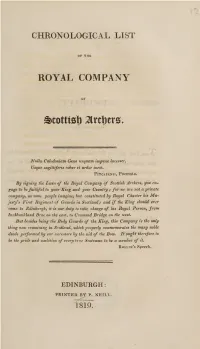

Chronological List of the Royal Company of Scottish Archers

CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF THE ROYAL COMPANY OF 2lrrt)er0. Nulla Caledoniam Gens unquarn impune laces set, Usque sagittiferis rohur et ardor inest. Pitcairnii, Poemata. By signing the Laws of the Royal Company of Scottish Archers, you en¬ gage to he faithful to your King and your Country ; for we are not a private company, as some people imagine, but constituted hy Royal Charter his Ma¬ jesty's First Regiment of Guards in Scotland; and if the King should ever come to Edinburgh, it is our duty to take charge of his Royal Person, from Inchbunkland Brae on the east, to Cramond Bridge on the west. But besides being the Body Guards of the King, this Company is the only thing now remaining in Scotland, which properly commemorates the many noble deeds performed by our ancestors by the aid of the Bow. It ought therefore to be the pride and ambition of every true Scotsman to be a member of it. Roslin’s Speech. EDINBURGH: PRINTED BY P. NEII.T.. 1819. PREFACE, T he first part of the following List, is not preserved in the handwriting of the Members themselves, and is not accurate with respect to dates; but the names are copied from the oldest Minute-books of the Company which have been preserved. The list from the 13th of May 1714, is copied from the Parchment Roll, which every Member subscribes with his own hand, in presence of the Council of the Company, when he receives his Diploma. Edinburgh, 1 5th July 1819* | f I LIST OF MEMBERS ADMITTED INTO THE ROYAL COMPANY OF SCOTTISH ARCHERS, FROM 1676, Extracted from Minute-books prior to the 13th of May 1714. -

Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites Teacher & Adult Helper

Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites Teacher & Adult Helper Notes Contents 1 Visiting the Exhibition 2 The Exhibition 3 Answers to the Trail Page 1 – Family Tree Page 2 – 1689 (James VII and II) Page 3 – 1708 (James VIII and III) Page 4 – 1745 (Bonnie Prince Charlie) 4 After your visit 5 Additional Resources National Museums Scotland Scottish Charity, No. SC011130 illustrations © Jenny Proudfoot www.jennyproudfoot.co.uk Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites Teacher & Adult Helper Notes 1 Introduction Explore the real story of Prince Charles Edward Stuart, better known as Bonnie Prince Charlie, and the rise and fall of the Jacobites. Step into the world of the Royal House of Stuart, one dynasty divided into two courts by religion, politics and war, each fighting for the throne of thethree kingdoms of Scotland, England and Ireland. Discover how four Jacobite kings became pawns in a much wider European political game. And follow the Jacobites’ fight to regain their lost kingdoms through five challenges to the throne, the last ending in crushing defeat at the Battle of Culloden and Bonnie Prince Charlie’s escape to the Isle of Skye and onwards to Europe. The schools trail will help your class explore the exhibition and the Jacobite story through three key players: James VII and II, James VIII and III and Bonnie Prince Charlie. 1. Visiting the Exhibition (Please share this information with your adult helpers) Page Character Year Exhibition sections Important information 1 N/A N/A The Stuart Dynasty and the Union of the Crowns • Food and drink is not permitted 2 James VII 1688 Dynasty restored, Dynasty • Photography is not allowed and II divided, A court in exile • When completing the trail, ensure pupils use a pencil 3 James VIII 1708- The challenges of James VIII and III 1715 and III, All roads lead to Rome • You will enter and exit via different doors. -

Trophy of the Edinburgh Society of Bowlers George R Dalgleish*

Proc SocAntiq Scot, 120 (1990), 189-200, The 'Silver Jack' trophy of the Edinburgh Society of Bowlers George R Dalgleish* '. doucer folk wysing a-jee The by as bowls on Tamson's green.' Allan Ramsay ABSTRACT This paper presents descriptiona 18th-century ofan sporting trophy investigatesand historythe of the society to which it was presented. INTRODUCTION In April 1986, the National Museums of Scotland bought, from a silver dealer in London, a unique 18th-century bowling trophy. Known as the 'Silver Jack', it was originally presented as an annual trophy to the Edinburgh Society of Bowlers in 1771 (NMS registration MEQ1594). The year before the Museums acquired it, it had appeared in an auction of Important English and Continental Silver hel Christie'y dYorb w kNe n (Christie'i s s 1985 t 1167),lo . Enquiries int histore os th it f yo previous ownership have, unfortunately, proved inconclusive, although it does seem it was in the possession of a London collector some time prior to its export to America. Despit e lac th f elateko r provenanc e extremel e 'Jackar th e r w ' fo e y fortunat o havet e considerable contemporary evidenc originas it r efo l presentatio e Societth r whico fo yt d t nhan i relates. This article will presen detailea t d descriptio trophe th thed f no y an n investigat historys eit , settin t withigi contexna histore spore th th f Edinburgto n f i tyo Scotlandd han . DESCRIPTION (illus 1) trophe Th y comprise silvesa r bowl morr ,o e accurately 'jack',a flattenef ,o d spherical form9 ,7 mm in diameter by 67 mm in width. -

Now the War Is Over

Pollard, T. and Banks, I. (2010) Now the wars are over: The past, present and future of Scottish battlefields. International Journal of Historical Archaeology,14 (3). pp. 414-441. ISSN 1092-7697. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/45069/ Deposited on: 17 November 2010 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Now the Wars are Over: the past, present and future of Scottish battlefields Tony Pollard and Iain Banks1 Suggested running head: The past, present and future of Scottish battlefields Centre for Battlefield Archaeology University of Glasgow The Gregory Building Lilybank Gardens Glasgow G12 8QQ United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)141 330 5541 Fax: +44 (0)141 330 3863 Email: [email protected] 1 Centre for Battlefield Archaeology, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland 1 Abstract Battlefield archaeology has provided a new way of appreciating historic battlefields. This paper provides a summary of the long history of warfare and conflict in Scotland which has given rise to a large number of battlefield sites. Recent moves to highlight the archaeological importance of these sites, in the form of Historic Scotland’s Battlefields Inventory are discussed, along with some of the problems associated with the preservation and management of these important cultural sites. 2 Keywords Battlefields; Conflict Archaeology; Management 3 Introduction Battlefield archaeology is a relatively recent development within the field of historical archaeology, which, in the UK at least, has itself not long been established within the archaeological mainstream. Within the present context it is noteworthy that Scotland has played an important role in this process, with the first international conference devoted to battlefield archaeology taking place at the University of Glasgow in 2000 (Freeman and Pollard, 2001).