St Andrews Cathedral & St Mary's Church, Kirkheugh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Soldier Fights for Three Separate but Sometimes Associated Reasons: for Duty, for Payment and for Cause

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stirling Online Research Repository The press and military conflict in early modern Scotland by Alastair J. Mann A soldier fights for three separate but sometimes associated reasons: for duty, for payment and for cause. Nathianiel Hawthorne once said of valour, however, that ‘he is only brave who has affections to fight for’. Those soldiers who are prepared most readily to risk their lives are those driven by political and religious passions. From the advent of printing to the present day the printed word has provided governments and generals with a means to galvanise support and to delineate both the emotional and rational reasons for participation in conflict. Like steel and gunpowder, the press was generally available to all military propagandists in early modern Europe, and so a press war was characteristic of outbreaks of civil war and inter-national war, and thus it was for those conflicts involving the Scottish soldier. Did Scotland’s early modern soldiers carry print into battle? Paul Huhnerfeld, the biographer of the German philosopher and Nazi Martin Heidegger, provides the curious revelation that German soldiers who died at the Russian front in the Second World War were to be found with copies of Heidegger’s popular philosophical works, with all their nihilism and anti-Semitism, in their knapsacks.1 The evidence for such proximity between print and combat is inconclusive for early modern Scotland, at least in any large scale. Officers and military chaplains certainly obtained religious pamphlets during the covenanting period from 1638 to 1651. -

126613853.23.Pdf

Sc&- PUBLICATIONS OF THE SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY VOLUME LIV STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH OCTOBEK 190' V STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH 1225-1559 Being a Translation of CONCILIA SCOTIAE: ECCLESIAE SCOTI- CANAE STATUTA TAM PROVINCIALIA QUAM SYNODALIA QUAE SUPERSUNT With Introduction and Notes by DAVID PATRICK, LL.D. Printed at the University Press by T. and A. Constable for the Scottish History Society 1907 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION— i. The Celtic Church in Scotland superseded by the Church of the Roman Obedience, . ix ir. The Independence of the Scottish Church and the Institution of the Provincial Council, . xxx in. Enormia, . xlvii iv. Sources of the Statutes, . li v. The Statutes and the Courts, .... Ivii vi. The Significance of the Statutes, ... lx vii. Irreverence and Shortcomings, .... Ixiv vni. Warying, . Ixx ix. Defective Learning, . Ixxv x. De Concubinariis, Ixxxvii xi. A Catholic Rebellion, ..... xciv xn. Pre-Reformation Puritanism, . xcvii xiii. Unpublished Documents of Archbishop Schevez, cvii xiv. Envoy, cxi List of Bishops and Archbishops, . cxiii Table of Money Values, cxiv Bull of Pope Honorius hi., ...... 1 Letter of the Conservator, ...... 1 Procedure, ......... 2 Forms of Excommunication, 3 General or Provincial Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, 8 Aberdeen Synodal Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, 30 Ecclesiastical Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, . 46 Constitutions of Bishop David of St. Andrews, . 57 St. Andrews Synodal Statutes of the Fourteenth Century, vii 68 viii STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH Provincial and Synodal Statute of the Fifteenth Century, . .78 Provincial Synod and General Council of 1420, . 80 General Council of 1459, 82 Provincial Council of 1549, ...... 84 General Provincial Council of 1551-2 ... -

A Singular Solace: an Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000

A Singular Solace: An Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000 David William Dutton BA, MTh October 2020 This dissertation is submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Stirling for the degree of Master of Philosophy in History. Division of History and Politics 1 Research Degree Thesis Submission Candidates should prepare their thesis in line with the code of practice. Candidates should complete and submit this form, along with a soft bound copy of their thesis for each examiner, to: Student Services Hub, 2A1 Cottrell Building, or to [email protected]. Candidate’s Full Name: DAVID WILLIAM DUTTON Student ID: 2644948 Thesis Word Count: 49,936 Maximum word limits include appendices but exclude footnotes and bibliographies. Please tick the appropriate box MPhil 50,000 words (approx. 150 pages) PhD 80,000 words (approx. 300 pages) PhD (by publication) 80,000 words (approx. 300 pages) PhD (by practice) 40,000 words (approx. 120 pages) Doctor of Applied Social Research 60,000 words (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Business Administration 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Education 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Midwifery / Nursing / Professional Health Studies 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Diplomacy 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Thesis Title: A Singular Solace: An Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000 Declaration I wish to submit the thesis detailed above in according with the University of Stirling research degree regulations. I declare that the thesis embodies the results of my own research and was composed by me. Where appropriate I have acknowledged the nature and extent of work carried out in collaboration with others included in the thesis. -

The Arms of the Baronial and Police Burghs of Scotland

'^m^ ^k: UC-NRLF nil! |il!|l|ll|ll|l||il|l|l|||||i!|||!| C E 525 bm ^M^ "^ A \ THE ARMS OF THE BARONIAL AND POLICE BURGHS OF SCOTLAND Of this Volume THREE HUNDRED AND Fifteen Copies have been printed, of which One Hundred and twenty are offered for sale. THE ARMS OF THE BARONIAL AND POLICE BURGHS OF SCOTLAND BY JOHN MARQUESS OF BUTE, K.T. H. J. STEVENSON AND H. W. LONSDALE EDINBURGH WILLIAM BLACKWOOD & SONS 1903 UNIFORM WITH THIS VOLUME. THE ARMS OF THE ROYAL AND PARLIAMENTARY BURGHS OF SCOTLAND. BY JOHN, MARQUESS OF BUTE, K.T., J. R. N. MACPHAIL, AND H. W. LONSDALE. With 131 Engravings on Wood and 11 other Illustrations. Crown 4to, 2 Guineas net. ABERCHIRDER. Argent, a cross patee gules. The burgh seal leaves no doubt of the tinctures — the field being plain, and the cross scored to indicate gules. One of the points of difference between the bearings of the Royal and Parliamentary Burghs on the one hand and those of the I Police Burghs on the other lies in the fact that the former carry castles and ships to an extent which becomes almost monotonous, while among the latter these bearings are rare. On the other hand, the Police Burghs very frequently assume a charge of which A 079 2 Aberchirder. examples, in the blazonry of the Royal and Parliamentary Burghs, are very rare : this is the cross, derived apparently from the fact that their market-crosses are the most prominent of their ancient monuments. In cases where the cross calvary does not appear, a cross of some other kind is often found, as in the present instance. -

Scottish Supreme Starting at $3319.00*

Scottish Supreme Starting at $3319.00* Live a luxe life among the lochs Trip details This heart of Scotland tour showcases the country's Tour start Tour end Trip Highlights: gorgeous castles, cathedrals, and countryside. Enjoy an Glasgow Edinburgh • Loch Ness Cruise intimate small group tour with luxury accommodations • Glamis Castle at every stop. 8 7 12 • Traditional Afternoon Tea Days Nights Meals • St Andrews Castle & Cathedral • Whisky Experience • Cawdor Castle • Stirling Castle Hotels: • DoubleTree by Hilton Dunblane Hydro • Ness Walk • Fairmont St Andrews Hotel • The Dunstane Houses 2020 Scottish Supreme - 8 days/7 nights Trip Itinerary Day 1 Arrival in Dunblane Day 2 Stirling Castle | The Trossachs Your tour starts with a traditional Scottish afternoon tea at your hotel in Dunblane, Travel to the historic town of Stirling to visit Stirling Castle. Captured in the 13th 40 miles north of Glasgow. Your beautifully restored Victorian-style hotel is set on century from the English by William Wallace and then by Robert the Bruce, Stirling 10 acres of private grounds and offers an indoor pool, fitness room, sauna, steam Castle has featured largely throughout Scottish history. Drive through the stunning room, and whirlpool. In the evening meet your tour director and fellow travelers for scenery of the Trossachs National Park before returning to your hotel for some a welcome drink before dinner. (D) leisure time before dinner. (B, D) Day 4 Johnstons of Elgin | Distillery Tour | Cawdor Castle Day 3 Urquhart Castle | Loch Ness Cruise Visit Johnstons of Elgin to discover the 220-year-old story of Scottish innovation and luxury, and learn how local craftspeople have collaborated with generations of herding communities from Mongolia, China, Afghanistan, Australia, and Peru to Drive across the haunting Rannoch Moor and through Glencoe, often considered create the finest woolen and cashmere cloth and accessories. -

A Memorial Volume of St. Andrews University In

DUPLICATE FROM THE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY, ST. ANDREWS, SCOTLAND. GIFT OF VOTIVA TABELLA H H H The Coats of Arms belong respectively to Alexander Stewart, natural son James Kennedy, Bishop of St of James IV, Archbishop of St Andrews 1440-1465, founder Andrews 1509-1513, and John Hepburn, Prior of St Andrews of St Salvator's College 1482-1522, cofounders of 1450 St Leonard's College 1512 The University- James Beaton, Archbishop of St Sir George Washington Andrews 1 522-1 539, who com- Baxter, menced the foundation of St grand-nephew and representative Mary's College 1537; Cardinal of Miss Mary Ann Baxter of David Beaton, Archbishop 1539- Balgavies, who founded 1546, who continued his brother's work, and John Hamilton, Arch- University College bishop 1 546-1 57 1, who com- Dundee in pleted the foundation 1880 1553 VOTIVA TABELLA A MEMORIAL VOLUME OF ST ANDREWS UNIVERSITY IN CONNECTION WITH ITS QUINCENTENARY FESTIVAL MDCCCCXI MCCCCXI iLVal Quo fit ut omnis Votiva pateat veluti descripta tabella Vita senis Horace PRINTED FOR THE UNIVERSITY BY ROBERT MACLEHOSE AND COMPANY LIMITED MCMXI GIF [ Presented by the University PREFACE This volume is intended primarily as a book of information about St Andrews University, to be placed in the hands of the distinguished guests who are coming from many lands to take part in our Quincentenary festival. It is accordingly in the main historical. In Part I the story is told of the beginning of the University and of its Colleges. Here it will be seen that the University was the work in the first instance of Churchmen unselfishly devoted to the improvement of their country, and manifesting by their acts that deep interest in education which long, before John Knox was born, lay in the heart of Scotland. -

The History of Scotland from the Accession of Alexander III. to The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT LOS ANGELES THE GIFT OF MAY TREAT MORRISON IN MEMORY OF ALEXANDER F MORRISON THE A 1C MEMORIAL LIBRARY HISTORY OF THE HISTORY OF SCOTLAND, ACCESSION OF ALEXANDEB III. TO THE UNION. BY PATRICK FRASER TYTLER, ** F.RS.E. AND F.A.S. NEW EDITION. IN TEN VOLUMES. VOL. X. EDINBURGH: WILLIAM P. NIMMO. 1866. MUEKAY AND OIBB, PUINTERS. EDI.VBUKOII V.IC INDE X. ABBOT of Unreason, vi. 64 ABELARD, ii. 291 ABERBROTHOC, i. 318, 321 ; ii. 205, 207, 230 Henry, Abbot of, i. 99, Abbots of, ii. 206 Abbey of, ii. 205. See ARBROATH ABERCORN. Edward I. of England proceeds to, i. 147 Castle of, taken by James II. iv. 102, 104. Mentioned, 105 ABERCROMBY, author of the Martial Achievements, noticed, i. 125 n.; iv. 278 David, Dean of Aberdeen, iv. 264 ABERDEEN. Edward I. of England passes through, i. 105. Noticed, 174. Part of Wallace's body sent to, 186. Mentioned, 208; ii. Ill, n. iii. 148 iv. 206, 233 234, 237, 238, 248, 295, 364 ; 64, ; 159, v. vi. vii. 267 ; 9, 25, 30, 174, 219, 241 ; 175, 263, 265, 266 ; 278, viii. 339 ; 12 n.; ix. 14, 25, 26, 39, 75, 146, 152, 153, 154, 167, 233-234 iii. Bishop of, noticed, 76 ; iv. 137, 178, 206, 261, 290 ; v. 115, n. n. vi. 145, 149, 153, 155, 156, 167, 204, 205 242 ; 207 Thomas, bishop of, iv. 130 Provost of, vii. 164 n. Burgesses of, hanged by order of Wallace, i. 127 Breviary of, v. 36 n. Castle of, taken by Bruce, i. -

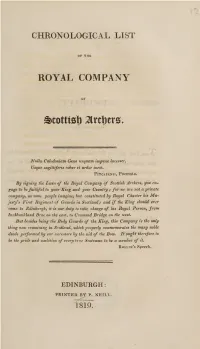

Chronological List of the Royal Company of Scottish Archers

CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF THE ROYAL COMPANY OF 2lrrt)er0. Nulla Caledoniam Gens unquarn impune laces set, Usque sagittiferis rohur et ardor inest. Pitcairnii, Poemata. By signing the Laws of the Royal Company of Scottish Archers, you en¬ gage to he faithful to your King and your Country ; for we are not a private company, as some people imagine, but constituted hy Royal Charter his Ma¬ jesty's First Regiment of Guards in Scotland; and if the King should ever come to Edinburgh, it is our duty to take charge of his Royal Person, from Inchbunkland Brae on the east, to Cramond Bridge on the west. But besides being the Body Guards of the King, this Company is the only thing now remaining in Scotland, which properly commemorates the many noble deeds performed by our ancestors by the aid of the Bow. It ought therefore to be the pride and ambition of every true Scotsman to be a member of it. Roslin’s Speech. EDINBURGH: PRINTED BY P. NEII.T.. 1819. PREFACE, T he first part of the following List, is not preserved in the handwriting of the Members themselves, and is not accurate with respect to dates; but the names are copied from the oldest Minute-books of the Company which have been preserved. The list from the 13th of May 1714, is copied from the Parchment Roll, which every Member subscribes with his own hand, in presence of the Council of the Company, when he receives his Diploma. Edinburgh, 1 5th July 1819* | f I LIST OF MEMBERS ADMITTED INTO THE ROYAL COMPANY OF SCOTTISH ARCHERS, FROM 1676, Extracted from Minute-books prior to the 13th of May 1714. -

Trophy of the Edinburgh Society of Bowlers George R Dalgleish*

Proc SocAntiq Scot, 120 (1990), 189-200, The 'Silver Jack' trophy of the Edinburgh Society of Bowlers George R Dalgleish* '. doucer folk wysing a-jee The by as bowls on Tamson's green.' Allan Ramsay ABSTRACT This paper presents descriptiona 18th-century ofan sporting trophy investigatesand historythe of the society to which it was presented. INTRODUCTION In April 1986, the National Museums of Scotland bought, from a silver dealer in London, a unique 18th-century bowling trophy. Known as the 'Silver Jack', it was originally presented as an annual trophy to the Edinburgh Society of Bowlers in 1771 (NMS registration MEQ1594). The year before the Museums acquired it, it had appeared in an auction of Important English and Continental Silver hel Christie'y dYorb w kNe n (Christie'i s s 1985 t 1167),lo . Enquiries int histore os th it f yo previous ownership have, unfortunately, proved inconclusive, although it does seem it was in the possession of a London collector some time prior to its export to America. Despit e lac th f elateko r provenanc e extremel e 'Jackar th e r w ' fo e y fortunat o havet e considerable contemporary evidenc originas it r efo l presentatio e Societth r whico fo yt d t nhan i relates. This article will presen detailea t d descriptio trophe th thed f no y an n investigat historys eit , settin t withigi contexna histore spore th th f Edinburgto n f i tyo Scotlandd han . DESCRIPTION (illus 1) trophe Th y comprise silvesa r bowl morr ,o e accurately 'jack',a flattenef ,o d spherical form9 ,7 mm in diameter by 67 mm in width. -

The Edinburgh History of Education in Scotland

The Edinburgh History of Education in Scotland Edited by Robert Anderson, Mark Freeman and Lindsay Paterson © editorial matter and organisation Robert Anderson, Mark Freeman and Lindsay Paterson, 2015 © the chapters, their several authors, 2015 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ www.euppublishing.com Typeset in 10/12 Goudy Old Style by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Stockport, Cheshire, printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7486 7915 7 (hardback) ISBN 978 0 7486 7916 4 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 0 7486 7917 1 (epub) The right of the contributors to be identified as authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). Contents List of Figures and Tables vii Acknowledgements viii Editors’ Introduction 1 Robert Anderson, Mark Freeman and Lindsay Paterson 1 Education in Scotland from 1000 to 1300 8 Matthew Hammond 2 ‘Through the Keyhole of the Monastic Library Door’: Learning and Education in Scottish Medieval Monasteries 25 Kimm Curran 3 Schooling in the Towns, c. 1400–c. 1560 39 Elizabeth Ewan 4 Education in the Century of Reformation 57 Stephen Mark Holmes 5 Urban Schooling in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth- century Scotland 79 Lindy Moore 6 The Universities and the Scottish Enlightenment 97 David Allan 7 Legal Education, 1650–1850 114 John Finlay 8 Scottish Schooling in the Denominational Era 133 John Stevenson 9 Education in Rural Scotland, 1696–1872 153 Ewen A. -

Memorials of Angus and Mearns, an Account, Historical, Antiquarian, and Traditionary

j m I tm &Cfi mm In^fl^fSm MEMORIALS OF ANGUS AND THE MEARNS AN ACCOUNT HISTORICAL, ANTIQUARIAN, AND TRADITIONARY, OF THE CASTLES AND TOWNS VISITED BY EDWARD L, AND OF THE BARONS, CLERGY, AND OTHERS WHO SWORE FEALTY TO ENGLAND IN 1291-6 ; ALSO OF THE ABBEY OF CUPAR AND THE PRIORY OF RESTENNETH, By the late ANDREW JERVISE, F.SA. SCOT. " DISTRICT EXAMINER OF REGISTERS ; AUTHOR OF THE LAND OF THE LINDSAYS," "EPITAPHS AND INSCRIPTIONS," ETC. REWRITTEN AND CORRECTED BY Rev. JAMES GAMMACK, M.A. Aberdeen CORRESPONDING MEMBER OF THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES, SCOTLAND ; AND MEMBER OF THE CAMBRIAN ARCH/EOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION. *v MEMORIALS OF ANGUS and M EARNS AN ACCOUNT HISTORICAL, ANTIQUARIAN, S* TRADITIONARY. VOL. I. EDINBURGH: DAVID DOUGLAS M DCCC LXXXV TO THE EIGHT HONOURABLE 31ame& SIXTH, AND BUT FOR THE ATTAINDER NINTH, EAEL OF SOUTHESK, BARON CARNEGIE OF KINNAIRD AND LEUCHARS, SIXTH BARONET OF PITTARROW, FIRST BARON BALINHARD OF FARNELL, AND A KNIGHT OF THE MOST ANCIENT AND MOST NOBLE ORDER OF THE THISTLE, Sins Seconn tuition IN IS, ACKNOWLEDGMENT OF MANY FAVOURS, MOST RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED, BY THE EDITOR VOL. I. EDITORS PBEFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION. As the Eirst Edition of this work was evidently an object of much satisfaction to the Author, and as its authority has been recognised by its being used so freely by later writers, I have felt in preparing this Second Edition that I was acting under a weighty responsibility both to the public and to Mr. Jervise's memory. Many fields have presented themselves for independent research, but as the plan of the work and its limits belonged to the author and not to the editor, I did not feel justified in materially altering either of them. -

Sueno's Stone, on the Northern Outskirts of Forres, Is a 6.5M-High Cross-Slab, the Tallest Piece of Early Historic Sculpture in Scotland

Property in Care no: 309 Designations: Scheduled Monument (90292) Taken into State care: 1923 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2015 HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE SUENO’S STONE We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE SUENO’S STONE CONTENTS 1 Summary 2 1.1 Introduction 2 1.2 Statement of significance 2 2 Assessment of values 3 2.1 Background 3 2.2 Evidential values 5 2.3 Historical values 5 2.4 Architectural and artistic values 6 2.5 Landscape and aesthetic values 7 2.6 Natural heritage values 8 2.7 Contemporary/use values 8 3 Major gaps in understanding 10 4 Associated properties 10 5 Keywords 10 Bibliography 10 APPENDICES Appendix 1: Timeline 11 Appendix 2: Summary of archaeological investigations 12 Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH 1 1 Summary 1.1 Introduction Sueno's Stone, on the northern outskirts of Forres, is a 6.5m-high cross-slab, the tallest piece of early historic sculpture in Scotland. It probably dates to the late first millennia AD.(The name Sueno, current from around 1700 and apparently in tribute to Svein Forkbeard, an 11th-century Danish king, is entirely without foundation.) In 1991 the stone was enclosed in a glass shelter to protect it from further erosion.