To the Quality of the Translation of Olivier Cunin's Text

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia. A bibliography of historical and modern texts with introduction and partial annotation, and some echoes in Western countries. [This annotated bibliography of 220 items suggests the range and major themes of how Buddhism and people influenced by Buddhism have responded to disability in Asia through two millennia, with cultural background. Titles of the materials may be skimmed through in an hour, or the titles and annotations read in a day. The works listed might take half a year to find and read.] M. Miles (compiler and annotator) West Midlands, UK. November 2013 Available at: http://www.independentliving.org/miles2014a and http://cirrie.buffalo.edu/bibliography/buddhism/index.php Some terms used in this bibliography Buddhist terms and people. Buddhism, Bouddhisme, Buddhismus, suffering, compassion, caring response, loving kindness, dharma, dukkha, evil, heaven, hell, ignorance, impermanence, kamma, karma, karuna, metta, noble truths, eightfold path, rebirth, reincarnation, soul, spirit, spirituality, transcendent, self, attachment, clinging, delusion, grasping, buddha, bodhisatta, nirvana; bhikkhu, bhikksu, bhikkhuni, samgha, sangha, monastery, refuge, sutra, sutta, bonze, friar, biwa hoshi, priest, monk, nun, alms, begging; healing, therapy, mindfulness, meditation, Gautama, Gotama, Maitreya, Shakyamuni, Siddhartha, Tathagata, Amida, Amita, Amitabha, Atisha, Avalokiteshvara, Guanyin, Kannon, Kuan-yin, Kukai, Samantabhadra, Santideva, Asoka, Bhaddiya, Khujjuttara, -

A Abbasid Caliphate, 239 Relations Between Tang Dynasty China And

INDEX A anti-communist forces, 2 Abbasid Caliphate, 239 Antony, Robert, 200 relations between Tang Dynasty “Apollonian” culture, 355 China and, 240 archaeological research in Southeast Yang Liangyao’s embassy to, Asia, 43, 44, 70 242–43, 261 aromatic resins, 233 Zhenyuan era (785–805), 242, aromatic timbers, 230 256 Arrayed Tales aboriginal settlements, 175–76 (The Arrayed Tales of Collected Abramson, Marc, 81 Oddities from South of the Abu Luoba ( · ), 239 Passes Lĩnh Nam chích quái liệt aconite, 284 truyện), 161–62 Agai ( ), Princess, 269, 286 becoming traditions, 183–88 Age of Exploration, 360–61 categorizing stories, 163 agricultural migrations, 325 fox essence in, 173–74 Amarapura Guanyin Temple, 314n58 and history, 165–70 An Dương Vương (also importance of, 164–65 known as Thục Phán ), 50, othering savages, 170–79 165, 167 promotion of, 164–65 Angkor, 61, 62 savage tales, 179–83 Cham naval attack on, 153 stories in, 162–63 Angkor Wat, 151 versions of, 170 carvings in, 153 writing style, 164 Anglo-Burmese War, 294 Atwill, David, 327 Annan tuzhi [Treatise and Âu Lạc Maps of Annan], 205 kingdom, 49–51 anti-colonial movements, 2 polity, 50 371 15 ImperialChinaIndexIT.indd 371 3/7/15 11:53 am 372 Index B Biography of Hua Guan Suo (Hua Bạch Đằng River, 204 Guan Suo zhuan ), 317 Bà Lộ Savages (Bà Lộ man ), black clothing, 95 177–79 Blakeley, Barry B., 347 Ba Min tongzhi , 118, bLo sbyong glegs bam (The Book of 121–22 Mind Training), 283 baneful spirits, in medieval China, Blumea balsamifera, 216, 220 143 boat competitions, 144 Banteay Chhmar carvings, 151, 153 in southern Chinese local Baoqing siming zhi , traditions, 149 224–25, 231 boat racing, 155, 156. -

A STUDY of the NAMES of MONUMENTS in ANGKOR (Cambodia)

A STUDY OF THE NAMES OF MONUMENTS IN ANGKOR (Cambodia) NHIM Sotheavin Sophia Asia Center for Research and Human Development, Sophia University Introduction This article aims at clarifying the concept of Khmer culture by specifically explaining the meanings of the names of the monuments in Angkor, names that have existed within the Khmer cultural community.1 Many works on Angkor history have been researched in different fields, such as the evolution of arts and architecture, through a systematic analysis of monuments and archaeological excavation analysis, and the most crucial are based on Cambodian epigraphy. My work however is meant to shed light on Angkor cultural history by studying the names of the monuments, and I intend to do so by searching for the original names that are found in ancient and middle period inscriptions, as well as those appearing in the oral tradition. This study also seeks to undertake a thorough verification of the condition and shape of the monuments, as well as the mode of affixation of names for them by the local inhabitants. I also wish to focus on certain crucial errors, as well as the insufficiency of earlier studies on the subject. To begin with, the books written in foreign languages often have mistakes in the vocabulary involved in the etymology of Khmer temples. Some researchers are not very familiar with the Khmer language, and besides, they might not have visited the site very often, or possibly also they did not pay too much attention to the oral tradition related to these ruins, a tradition that might be known to the village elders. -

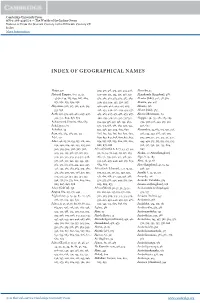

Index of Geographical Names

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42465-3 — The Worlds of the Indian Ocean Volume 2: From the Seventh Century to the Fifteenth Century CE Index More Information INDEX OF GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES Abaya, 571 309, 317, 318, 319, 320, 323, 328, Akumbu, 54 Abbasid Empire, 6–7, 12, 17, 329–370, 371, 374, 375, 376, 377, Alamkonda (kingdom), 488 45–70, 149, 185, 639, 667, 669, 379, 380, 382, 383, 384, 385, 389, Alaotra (lake), 401, 411, 582 671, 672, 673, 674, 676 390, 393, 394, 395, 396, 397, Alasora, 414, 427 Abyssinia, 306, 317, 322, 490, 519, 400, 401, 402, 409, 415, 425, Albania, 516 533, 656 426, 434, 440, 441, 449, 454, 457, Albert (lake), 365 Aceh, 198, 374, 425, 460, 497, 498, 463, 465, 467, 471, 478, 479, 487, Alborz Mountains, 69 503, 574, 609, 678, 679 490, 493, 519, 521, 534, 535–552, Aleppo, 149, 175, 281, 285, 293, Achaemenid Empire, 660, 665 554, 555, 556, 557, 558, 559, 569, 294, 307, 326, 443, 519, 522, Achalapura, 80 570, 575, 586, 588, 589, 590, 591, 528, 607 Achsiket, 49 592, 596, 597, 599, 603, 607, Alexandria, 53, 162, 175, 197, 208, Acre, 163, 284, 285, 311, 312 608, 611, 612, 615, 617, 620, 629, 216, 234, 247, 286, 298, 301, Adal, 451 630, 637, 647, 648, 649, 652, 653, 307, 309, 311, 312, 313, 315, 322, Aden, 46, 65, 70, 133, 157, 216, 220, 654, 657, 658, 659, 660, 661, 662, 443, 450, 515, 517, 519, 523, 525, 230, 240, 284, 291, 293, 295, 301, 668, 678, 688 526, 527, 530, 532, 533, 604, 302, 303, 304, 306, 307, 308, Africa (North), 6, 8, 17, 43, 47, 49, 607 309, 313, 315, 316, 317, 318, 319, 50, 52, 54, 70, 149, 151, 158, -

The Khmer Did Not Live by Rice Alone Archaeobotanical Investigations At

Archaeological Research in Asia 24 (2020) 100213 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Archaeological Research in Asia journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ara The Khmer did not live by rice alone: Archaeobotanical investigations at Angkor Wat and Ta Prohm T ⁎ Cristina Cobo Castilloa, , Alison Carterb, Eleanor Kingwell-Banhama, Yijie Zhuanga, Alison Weisskopfa, Rachna Chhayc, Piphal Hengd,f, Dorian Q. Fullera,e, Miriam Starkf a University College London, Institute of Archaeology, 31–34 Gordon Square, WC1H 0PY London, UK b University of Oregon, Department of Anthropology, 1218 University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97403, USA c Angkor International Centre of Research and Documentation, APSARA National Authority, Siem Reap, Cambodia d Northern Illinois University, Department of Anthropology, Center for Southeast Asian Studies, 520 College View Court, IL, USA e School of Archaeology and Museology, Northwest University, Xian, Shaanxi, China f University of Hawai'i at Manoa, Department of Anthropology, HI, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The Angkorian Empire was at its peak from the 10th to 13th centuries CE. It wielded great influence across Inscriptions mainland Southeast Asia and is now one of the most archaeologically visible polities due to its expansive re- Household gardens ligious building works. This paper presents archaeobotanical evidence from two of the most renowned Non-elites Angkorian temples largely associated with kings and elites, Angkor Wat and Ta Prohm. But it focuses on the Economic crops people that dwelt within the temple enclosures, some of whom were involved in the daily functions of the Rice temple. Archaeological work indicates that temple enclosures were areas of habitation within the Angkorian Cotton urban core and the temples and their enclosures were ritual, political, social, and economic landscapes. -

Archaeology Unit Archaeology Report Series

#8 NALANDA–SRIWIJAYA CENTRE ARCHAEOLOGY UNIT ARCHAEOLOGY REPORT SERIES Tonle Snguot: Preliminary Research Results from an Angkorian Hospital Site D. KYLE LATINIS, EA DARITH, KÁROLY BELÉNYESY, AND HUNTER I. WATSON A T F Archaeology Unit 6870 0955 facebook.com/nalandasriwijayacentre Nalanda–Sriwijaya Centre ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute F W 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace, 6778 1735 Singapore 119614 www.iseas.edu.sg/centres/nalanda-sriwijaya-centre E [email protected] The Nalanda–Sriwijaya Centre Archaeology Unit (NSC AU) Archaeology Report Series has been established to provide an avenue for publishing and disseminating archaeological and related research conducted or presented within the Centre. This also includes research conducted in partnership with the Centre as well as outside submissions from fields of enquiry relevant to the Centre's goals. The overall intent is to benefit communities of interest and augment ongoing and future research. The NSC AU Archaeology Report Series is published Citations of this publication should be made in the electronically by the Nalanda–Sriwijaya Centre of following manner: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. Latinis, D. K., Ea, D., Belényesy, K., and Watson, H. I. (2018). “Tonle Snguot: Preliminary Research Results from an © Copyright is held by the author/s of each report. Angkorian Hospital Site.” Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre Archaeology Unit Archaeology Report Series No. 8. ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute accepts no responsibility for facts presented and views expressed. Responsibility Cover image: Natalie Khoo rests exclusively with the individual author or authors. Authors have agreed that permission has been obtained from appropriate sources to include any Editor : Foo Shu Tieng content in the publication such as texts, images, maps, Cover Art Template : Aaron Kao tables, charts, graphs, illustrations, and photos that are Layout & Typesetting : Foo Shu Tieng not exclusively owned or copyrighted by the authors. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-19074-9 - The Cambridge World History: Volume V: Expanding Webs of Exchange and Conflict, 500 Ce–1500 Ce Edited by Benjamin Z . Kedar and Merry E. Wiesner-Hanks Index More information Index Aachen, 126, 180 Islam and educational institutions, 135–7 ‘Abbasid Baghdad, 186, 346 North, see North Africa. ‘Abbasids, 48, 100, 166, 187, 194, 200, 252, 398, northern, 681–2 411, 505–6 sub-Saharan, see sub-Saharan Africa. Caliphate, 24, 168, 199, 211, 213, 238, 252, West, see West Africa. 346, 402, 406 western coast of, 8, 254 Court, 180, 195, 199 Afro–Eurasia, 31, 33, 142, 667, 670–1, 674–7, ‘Abd al-Malik, 505 680, 682–3 Abd al-Rahman III, 346, 349 trade and commerce, 233–54 Abelard, Peter, 129 afterlife, 200, 546 absolutism, 99, 113 agrarian reformers, 52–3 Abu Ishaq al-Sahilil, 601 agricultural growth, 216, 626 Abu-Lughod, Janet, 634, 683 agricultural production, 220–1, 246, 318, Abū Mufarrij, Shaykh, 299–300, 302 336, 531 Acciaiuoli, 259, 266 agricultural societies, 95, 105, 669 Achaea, 580 agriculture, 20, 45, 53, 97–8, 100, 107, 148, adab, 191–2 334–6, 376–7, 669 adaptation, 22, 34–5, 328, 415, 476, 500, 559, permanent, 49, 54 668 rainfed, see rainfed agriculture. Aden, 4, 279, 301–4, 552, 674 wet-rice, 518, 525 administration, 123, 134, 180, 432–3, 532, 534, agro-literate societies, 212, 217, 225 539–42, 576–7 agro-urban civilizations, 29, 145, 149–50 centralized, 24, 332, 506, 578 Akroinon, 157, 564 imperial, 33, 555, 644 Albertus Magnus, 45 indirect, 539–40 alchemy, 125, 340 tax, 561, 570, 575, 577 Aleppo, -

Teaching the Silk Road

Introduction Morris Rossabi Globalization has become so identifi ed with the late twentieth and early twenty-fi rst centuries that it seems to overshadow earlier eras of international relations. Many in the modern world have associated such contacts with recent times, a view that prevailed in education as well. For example, most so-called World History courses in secondary schools and community colleges placed Europe at the center, consider- ing other civilizations principally when they interacted with the West. A global history perspective would reveal that globalization, in the form of East-West relations that signifi cantly infl uenced both, far predated the twentieth century. The World History Association pioneered such a global history approach. Established in the 1980s, it founded the Journal of World His- tory as an exemplar of the latest research that links political, cultural, and social interactions among civilizations. Textbooks with an emphasis on global history have proliferated over the past few decades. Many simply provide the history of individual civilizations in separate chapters, but a few have attempted to integrate developments in one part of the world with other regions. Such efforts at global history have gone beyond the previous Eurocentric views. Study of the Silk Roads, in particular, offers a unique means of conveying the signifi cance of intercultural relations. Although most historians date the origins of the Silk Roads with the Han dynasty mission of Zhang Qian to Central Asia in the second century,BCE, contacts between China and Central Asia no doubt preceded that time, as evidenced by scraps of silk (which only the Chinese then knew how to produce) in Middle Eastern tombs centuries before Zhang’s expedi- tion. -

Soli, Diplomaţi Şi Călători Chinezi În Spaţiul Eurasiatic

SOLI, DIPLOMAŢI ŞI CĂLĂTORI CHINEZI ÎN SPAŢIUL EURASIATIC. Scurtă privire istorică ANNA EVA BUDURA Spaţiul eurasiatic a oferit datorită reliefului şi cursurilor sale de ape condiţii favorabile formării rutelor de deplasare a locuitorilor săi încă din preistorie. Confirmarea acestui fapt istoric se găseşte cu prisosinţă în bogatul inventar al siturilor arheologice descoperite de-a lungul traiectoriilor acestor mişcări permanente de populaţii din est spre vest şi dinspre vest spre est, din sud spre nord şi nord spre sud. Centrele de cultură create de-a lungul acestora constituie repere de referinţă în istoria civilizaţiei umane, centre unde s-a realizat acea întrepătrundere a civilizaţiilor chineze şi indiene cu cele greco-romane şi arabe într-una ce poate să caracterizeze civilizaţia noastră eurasiatică, unde se simt urmele forfotei neamurilor fără astâmpăr, urmele sciţilor, yuezhilor, wusunilor, ale hunilor, turcilor şi mongolilor în avântata lor pornire, ba paşnică, ba războinică, spre vest, centre ce constituie moştenirea spirituală a tuturor seminţiilor de pe întregul continent eurasiatic şi a întregii omeniri. Una dintre aceste culturi, care s-a impus ca una din centrele de civilizaţie din estul Eurasiei, a fost creată de neamul huaxia care s-a format pe marele platou de loes, apoi s-a extins spre est, de-a lungul cursului mediu şi inferior al Râului Galben spre centrul Chinei şi spre China de nord. Aici cu 6 000-5 000 de ani în urmă a luat naştere cultura Yangshao a cărei ceramică colorată poate fi considerată primul mesager al civilizaţiei huaxia care a ajuns până în Europa centrală şi a găsit condiţii de înflorire maximă la Cucuteni, pe plaiurile României. -

SPAFA Digest 1981, Vol. 2, No. 1

4 Workshop Paper Exports of Chinese Porcelains Up to the Yuan Dynasty By Professor Feng Xian Ming Background to the Export of Chinese Porcelains China is known the world over as the "country of porcelains". Far back in the Eastern Han period, more than seventeen centuries ago, mature green- glaze porcelains appeared in Zhejiang province, thus completing the transition from proto-porcelains to full-fledged ceramics. During the Tang dynasty, porcelain-making techniques were further advanced. The green porcelains of Yuyao county, the white- porcelains of Lincheng county, the underglazed porcelains of Changsha and the three-colored porce- lains of Gongxian county won fame throughout the country for their unique local flavor and style. Chang'an, capital of the Tang dynasty, was one of the centers of international trade in the orient and its West Market was reserved for trade with foreign merchants. Products of the kilns of Yuyao, Lincheng, Changsha and Gongxian, appearing for the first time on the market in Chang'an, caused a sensation among foreign merchants who hunted around for specimens to take back to their own countries. The market for Tang dynasty porcelains grew. They were shipped overland on the old Silk Road and overseas in Arab and Chinese bottoms to many countries in Asia. In those days Chinese porcelains were unique, since no other Asian countries had them as yet. Moreover, they were much more attractive than pottery. Contributing Factors to Increased Exports In the Song dynasty, exports increased dramatical- ly both in volume and in the number of foreign mar- kets. There were five factors behind this development: 1. -

Chinese Sea Merchants and Pirates

Chinese Sea Merchants and Pirates 著者 Matsuura Akira journal or A Selection of Essays on Oriental Studies of publication title ICIS page range 63-84 year 2011-03-31 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10112/4345 Chinese Sea Merchants and Pirates MATSUURA Akira Key words: Chinese Sea, Sea Merchants, Pinates, Junks, East Asia Introduction: the course of research in Chinese maritime history Studies of global maritime history have frequently dealt with questions involving the Mediterranean and Atlantic, focusing on the history of Western Europe. However, there have been few studies dealing specifically with the waters surrounding East Asia. It would be fair to say that up until now historical studies looking at the seas lying within the area contained by the Chinese mainland, the Korean penin- sula, the Japanese archipelago, the Ryukyu Islands, Taiwan, the Philippine and Indonesian archipelagos, the Malay peninsula, and mainland Indochina, namely the Bohai, Yellow, East China and South China Seas, have been slow to appear. This is perhaps because existing studies of Chinese history have mostly taken a continental view of history, as Kawakatsu Heita points out in ‘Launching Maritime History’ (Kaiyō shikan no funade): ‘postwar Japanese have not had a view of history that takes account of the sea.’ It has been said that Chinese history emerged from the Yellow River basin. Although the importance of the culture of the Yangtze River basin has recently been acknowledged, the cultural activity of the maritime regions, with their broad coastline, has been neglected and for a long time has received little attention. As archaeological surveys of the coastal regions have progressed, the history of the maritime life of Chinese people living in coastal areas has gradually come to be re-thought. -

The Trouble with Mechanized Farming

EASTM 23 (2005): 54-78 Maritime Travel and the Question of Provisions and Scurvy in a Chinese Context Mathieu Torck [Mathieu Torck is currently PhD-student at the Department of Languages and Cultures of South and East Asia at Ghent University (Belgium). His current research deals with the history of provisioning on land and at sea and involves such areas as Chinese maritime and military history, food science and migra- tion.] * * * Introduction In the long course of human history people have always been on the move. In fact, human history is characterized by a seemingly incessant process of migration. Even when the settlement of certain populations had reached its conclusive phase and the great cultural areas of the world had developed, there were still those who moved from one place to another in small or large numbers. The reasons for this movement are many. One can easily think of situations in which demographic and economic factors force people to look for a better place to reside, while voyages of discovery, inspired by whatever purpose, have always existed and been vividly remembered in the collective memory of many a nation. When one approaches the subjects of voyages, travel, migration, etc., one must also take account of the importance of provisioning. In the West, in medieval times and after, a lack of provisions often led to the much feared nutritional deficiency disease scurvy. As is commonly known, the problem of scurvy has everything to do with vitamin C. The disease occurs when the level of vitamin C in the human body is too low, the result of a scarcity or total absence of fresh fruit or vegetables in the daily diet.