A Review of Sources for Visualising the Royal Palace of Angkor, Cambodia, in the 13Th Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia. A bibliography of historical and modern texts with introduction and partial annotation, and some echoes in Western countries. [This annotated bibliography of 220 items suggests the range and major themes of how Buddhism and people influenced by Buddhism have responded to disability in Asia through two millennia, with cultural background. Titles of the materials may be skimmed through in an hour, or the titles and annotations read in a day. The works listed might take half a year to find and read.] M. Miles (compiler and annotator) West Midlands, UK. November 2013 Available at: http://www.independentliving.org/miles2014a and http://cirrie.buffalo.edu/bibliography/buddhism/index.php Some terms used in this bibliography Buddhist terms and people. Buddhism, Bouddhisme, Buddhismus, suffering, compassion, caring response, loving kindness, dharma, dukkha, evil, heaven, hell, ignorance, impermanence, kamma, karma, karuna, metta, noble truths, eightfold path, rebirth, reincarnation, soul, spirit, spirituality, transcendent, self, attachment, clinging, delusion, grasping, buddha, bodhisatta, nirvana; bhikkhu, bhikksu, bhikkhuni, samgha, sangha, monastery, refuge, sutra, sutta, bonze, friar, biwa hoshi, priest, monk, nun, alms, begging; healing, therapy, mindfulness, meditation, Gautama, Gotama, Maitreya, Shakyamuni, Siddhartha, Tathagata, Amida, Amita, Amitabha, Atisha, Avalokiteshvara, Guanyin, Kannon, Kuan-yin, Kukai, Samantabhadra, Santideva, Asoka, Bhaddiya, Khujjuttara, -

![Bibliography [PDF] (97.67Kb)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4717/bibliography-pdf-97-67kb-824717.webp)

Bibliography [PDF] (97.67Kb)

WORKS CITED Atlas Colonial illustré Paris: Librarie Larousse, 1905. Bal, Mieke. Double Exposures The Subject of Cultural Analysis. New York: Routledge, 1996. Benjamin, Walter. “The Task of the Translator,” Illuminations Essays and Reflections New York: Schocken Books, 1969. Benoit, Pierre. Le Roi Lépreux. Paris: Kailash Éditions, 2000. Bingham, Robert. Lightening on the Sun. New York: Doubleday, 2000. Black, Jeremy. The British Abroad the Grand Tour in the Eighteenth Century. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1992. Bouillevaux, C. E. Ma visite aux ruines cambodgiennes en 1850 Sanit-Quentin: Imprimerie J. Monceau, 1874. ———. Voyage Dans L'indo-Chine 1848-1856. Paris: Librarie de Victor Palmé, 1858. Carné, Louis de. Travels on the Mekong : Cambodia, Laos and Yunnan, the Political and Trade Report of the Mekong Exploration Commission (June 1866-June 1868). Bangkok: White Lotus, 2000. David Chandler, “An Anti-Vietnamese Rebellion in Early Nineteenth Century Cambodia”, Facing the Cambodian Past, Bangkok, Silkworm Books, 1996b. ———. "Assassination of Résident Bardez." In Facing the Cambodian Past: Selected Essays 1971-1994. Chiang Mai: Silkworm, 1996b. ———. "Cambodian Royal Chronicles (Rajabangsavatar), 1927-1949: Kingship and Historiography at the End of the Colonial Era." In Facing the Cambodian Past : Selected Essays 1971-1994, vi, [1], 331. Chiang Mai: Silkworn Books, 1996b. ———. A History of Cambodia. Second ed. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 1996a. ———. "Seeing Red: Perceptions of Cambodian History in Democratic Kampuchea." In Facing the Cambodian Past Selected Essays 1971-1994. Chiang mai: Silkworm Books, 1996b. 216 217 ———. "Transformation in Cambodia." In Facing the Cambodian Past Selected Essays 1971-1994. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 1996b. Chimprabha, Marisa. "Anti-Thai Feelings Flare up in Cambodia." The Nation, May 10 2004. -

Post/Colonial Discourses on the Cambodian Court Dance

Kyoto University Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 42, No. 4, 東南アジア研究 March 2005 42巻 4 号 Post/colonial Discourses on the Cambodian Court Dance SASAGAWA Hideo* Abstract Under the reign of King Ang Duong in the middle of nineteenth century, Cambodia was under the influence of Siamese culture. Although Cambodia was colonized by France in 1863, the royal troupe of the dance still performed Siamese repertoires. It was not until the cession of the Angkor monuments from Siam in 1907 that Angkor began to play a central role in French colonial discourse. George Groslier’s works inter alia were instrumental in historicizing the court dance as a “tradition” handed down from the Angkorean era. Groslier appealed to the colonial authorities for the protection of this “tradition” which had allegedly been on the “decline” owing to the influence of French culture. In the latter half of the 1920s the Résident Supérieur au Cambodge temporarily succeeded in transferring the royal troupe to Groslier’s control. In the 1930s members of the royal family set out to reconstruct the troupe, and the Minister of Palace named Thiounn wrote a book in which he described the court dance as Angkorean “tradition.” His book can be considered to be an attempt to appropriate colonial discourse and to construct a new narrative for the Khmers. After independence in 1953 French colonial discourse on Angkor was incorporated into Cam- bodian nationalism. While new repertoires such as Apsara Dance, modeled on the relief of the monuments, were created, the Buddhist Institute in Phnom Penh reprinted Thiounn’s book. Though the civil war was prolonged for 20 years and the Pol Pot regime rejected Cambodian cul- ture with the exception of the Angkor monuments, French colonial discourse is still alive in Cam- bodia today. -

A Abbasid Caliphate, 239 Relations Between Tang Dynasty China And

INDEX A anti-communist forces, 2 Abbasid Caliphate, 239 Antony, Robert, 200 relations between Tang Dynasty “Apollonian” culture, 355 China and, 240 archaeological research in Southeast Yang Liangyao’s embassy to, Asia, 43, 44, 70 242–43, 261 aromatic resins, 233 Zhenyuan era (785–805), 242, aromatic timbers, 230 256 Arrayed Tales aboriginal settlements, 175–76 (The Arrayed Tales of Collected Abramson, Marc, 81 Oddities from South of the Abu Luoba ( · ), 239 Passes Lĩnh Nam chích quái liệt aconite, 284 truyện), 161–62 Agai ( ), Princess, 269, 286 becoming traditions, 183–88 Age of Exploration, 360–61 categorizing stories, 163 agricultural migrations, 325 fox essence in, 173–74 Amarapura Guanyin Temple, 314n58 and history, 165–70 An Dương Vương (also importance of, 164–65 known as Thục Phán ), 50, othering savages, 170–79 165, 167 promotion of, 164–65 Angkor, 61, 62 savage tales, 179–83 Cham naval attack on, 153 stories in, 162–63 Angkor Wat, 151 versions of, 170 carvings in, 153 writing style, 164 Anglo-Burmese War, 294 Atwill, David, 327 Annan tuzhi [Treatise and Âu Lạc Maps of Annan], 205 kingdom, 49–51 anti-colonial movements, 2 polity, 50 371 15 ImperialChinaIndexIT.indd 371 3/7/15 11:53 am 372 Index B Biography of Hua Guan Suo (Hua Bạch Đằng River, 204 Guan Suo zhuan ), 317 Bà Lộ Savages (Bà Lộ man ), black clothing, 95 177–79 Blakeley, Barry B., 347 Ba Min tongzhi , 118, bLo sbyong glegs bam (The Book of 121–22 Mind Training), 283 baneful spirits, in medieval China, Blumea balsamifera, 216, 220 143 boat competitions, 144 Banteay Chhmar carvings, 151, 153 in southern Chinese local Baoqing siming zhi , traditions, 149 224–25, 231 boat racing, 155, 156. -

A STUDY of the NAMES of MONUMENTS in ANGKOR (Cambodia)

A STUDY OF THE NAMES OF MONUMENTS IN ANGKOR (Cambodia) NHIM Sotheavin Sophia Asia Center for Research and Human Development, Sophia University Introduction This article aims at clarifying the concept of Khmer culture by specifically explaining the meanings of the names of the monuments in Angkor, names that have existed within the Khmer cultural community.1 Many works on Angkor history have been researched in different fields, such as the evolution of arts and architecture, through a systematic analysis of monuments and archaeological excavation analysis, and the most crucial are based on Cambodian epigraphy. My work however is meant to shed light on Angkor cultural history by studying the names of the monuments, and I intend to do so by searching for the original names that are found in ancient and middle period inscriptions, as well as those appearing in the oral tradition. This study also seeks to undertake a thorough verification of the condition and shape of the monuments, as well as the mode of affixation of names for them by the local inhabitants. I also wish to focus on certain crucial errors, as well as the insufficiency of earlier studies on the subject. To begin with, the books written in foreign languages often have mistakes in the vocabulary involved in the etymology of Khmer temples. Some researchers are not very familiar with the Khmer language, and besides, they might not have visited the site very often, or possibly also they did not pay too much attention to the oral tradition related to these ruins, a tradition that might be known to the village elders. -

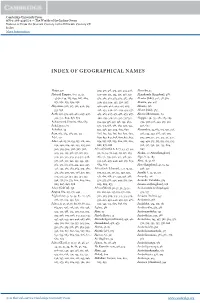

Index of Geographical Names

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42465-3 — The Worlds of the Indian Ocean Volume 2: From the Seventh Century to the Fifteenth Century CE Index More Information INDEX OF GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES Abaya, 571 309, 317, 318, 319, 320, 323, 328, Akumbu, 54 Abbasid Empire, 6–7, 12, 17, 329–370, 371, 374, 375, 376, 377, Alamkonda (kingdom), 488 45–70, 149, 185, 639, 667, 669, 379, 380, 382, 383, 384, 385, 389, Alaotra (lake), 401, 411, 582 671, 672, 673, 674, 676 390, 393, 394, 395, 396, 397, Alasora, 414, 427 Abyssinia, 306, 317, 322, 490, 519, 400, 401, 402, 409, 415, 425, Albania, 516 533, 656 426, 434, 440, 441, 449, 454, 457, Albert (lake), 365 Aceh, 198, 374, 425, 460, 497, 498, 463, 465, 467, 471, 478, 479, 487, Alborz Mountains, 69 503, 574, 609, 678, 679 490, 493, 519, 521, 534, 535–552, Aleppo, 149, 175, 281, 285, 293, Achaemenid Empire, 660, 665 554, 555, 556, 557, 558, 559, 569, 294, 307, 326, 443, 519, 522, Achalapura, 80 570, 575, 586, 588, 589, 590, 591, 528, 607 Achsiket, 49 592, 596, 597, 599, 603, 607, Alexandria, 53, 162, 175, 197, 208, Acre, 163, 284, 285, 311, 312 608, 611, 612, 615, 617, 620, 629, 216, 234, 247, 286, 298, 301, Adal, 451 630, 637, 647, 648, 649, 652, 653, 307, 309, 311, 312, 313, 315, 322, Aden, 46, 65, 70, 133, 157, 216, 220, 654, 657, 658, 659, 660, 661, 662, 443, 450, 515, 517, 519, 523, 525, 230, 240, 284, 291, 293, 295, 301, 668, 678, 688 526, 527, 530, 532, 533, 604, 302, 303, 304, 306, 307, 308, Africa (North), 6, 8, 17, 43, 47, 49, 607 309, 313, 315, 316, 317, 318, 319, 50, 52, 54, 70, 149, 151, 158, -

The Role of a National Museum the Case of the National Museum of Cambodia

BALANCING POLITICAL HISTORY, ETHNOGRAPHY, AND ART: THE ROLE OF A NATIONAL MUSEUM THE CASE OF THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF CAMBODIA Mr. Kong Vireak Director, National Museum of Cambodia INTRODUCTION It is not without difculty that one can For its modest defnition, museums are discuss and debate the role of the Cambodian a major expression of cultural identity in every National Museum within this theme. In its society. The role of national museums in defning context of having been part of a French Protec- and shaping a nation’s identity has been a much torate, the National Museum of Cambodia was discussed topic of late. In introducing, perhaps, created with a mandate to cover archaeology the most stimulating collection of essays on the and art history but also to balance the colonial subject, Darryl McIntyre and Kirsten Wehner in history with the great past Cambodian civiliza- the introduction to their co-edited publication, tion. Since it opened till the present day, the Na- National Museums: Negotiating Histories – Con- tional Museum of Cambodia’s core collections The Exterior of the National Museum of Cambodia ference proceedings (2001), drew attention to the and displays center on archaeological and art Image courtesy of the National Museum of Cambodia difculties contemporary national museums objects, which include exclusively the statues of face in trying to “negotiate and present com- Indian Gods of Hinduism and Buddhism, with peting interpretations of national histories and the exception of a small number of pre-historic Mouhot(1826–1861), such as Travels in the Central and researchers. The discovery of Khmer sites national identities.”1 How national museums and ethnographic objects. -

Arts of Asia Lecture Series Fall 2016 from Monet to Ai Weiwei: How We Got Here Sponsored by the Society for Asian Art

Arts of Asia Lecture Series Fall 2016 From Monet to Ai Weiwei: How We Got Here Sponsored by The Society for Asian Art Artisans to Artists: Colonial and Post-Independence Art Education in Vietnam and Cambodia Prof. Nora A. Taylor, School of the Art Institute of Chicago September 30, 2016 Historical background: In the race for European domination of Asia, in 1862 the French obtained concessions from Vietnamese and Cambodia emperors to establish trade ports in Tonkin, Annam and Cochinchina, present-day Northern, Central and Southern Vietnam respectively. In 1863, they established the protectorate of Cambodia and in 1887, created the Indochina Union made up of the five territories of Tonkin, Annam, Cochinchina, Laos and Cambodia. The French exploited local resources such as rubber, cotton, tabacco, coffee and opium and also established its first art school in Phnom Penh under the directorship of George Groslier. In 1925, after suffering devastating losses in World War I, colonialism no longer seemed like a viable economic enterprise. Amidst increasing anti-colonial sentiment among French citizens, the colonial government changed its cultural policies in the colony from one of assimilation to association before abandoning the colony altogether in 1954. It was then that Ecole des Beaux-Arts de l’Indochine or the Indochina School of Fine Art was established in Hanoi. The two art schools could not be more different in its approach to education and illustrate well the contrast between the two policies. In 1931, the benefits of colonial art education were displayed at the Exposition Coloniale in Paris. This lecture will provide an overview of the influence of the two art schools on the development of modern art in Cambodia and Vietnam both during the colonial period and following independence. -

![Chapter One [PDF] (146.2Kb)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3524/chapter-one-pdf-146-2kb-2683524.webp)

Chapter One [PDF] (146.2Kb)

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION “Ah! poet, come here, at this lyrical hour, sit yourself down on these stones, still warm, and take in the calm atmosphere of these great things. Come chant the appropriate words, in the divine cadence, with each passing second. Allow your genius to rush forth freely: these dormant waters and all that they reflect, these stones and the heavens of the eternal sleep.” 1 -George Groslier, Director of the School of Cambodian Arts The first time that Henri Mouhot, the French naturalist who has often (erroneously) been credited with discovering Angkor, mentions the temples in his published journals he has not yet visited the monuments, but is sure that the ruins testify to Cambodia once having been a powerful and populous country.2 Before he has laid his eyes upon the ruins he has already decided that Angkor will be evidence of Cambodia’s need for assistance,3 which he quickly asserts should be provided by his own country, France. His words were written in 1861, just two years before France granted his wish by making Cambodia a French protectorate. Mouhot’s description, one of the earliest published European accounts of Angkor, is an important opening act in the relationship between Cambodia and France that developed over the ninety years of colonial rule. While Mouhot’s was among the earliest such descriptions, it was by no means the last. He would be 1 George Groslier, A L'ombre D'angkor (Paris: Augustin Challamel, 1916), p. 103. 2 Henri Mouhot, Travels in Siam, Cambodia, Laos, and Annam (Bangkok: White Lotus Press, 2000) pp. -

The Khmer Did Not Live by Rice Alone Archaeobotanical Investigations At

Archaeological Research in Asia 24 (2020) 100213 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Archaeological Research in Asia journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ara The Khmer did not live by rice alone: Archaeobotanical investigations at Angkor Wat and Ta Prohm T ⁎ Cristina Cobo Castilloa, , Alison Carterb, Eleanor Kingwell-Banhama, Yijie Zhuanga, Alison Weisskopfa, Rachna Chhayc, Piphal Hengd,f, Dorian Q. Fullera,e, Miriam Starkf a University College London, Institute of Archaeology, 31–34 Gordon Square, WC1H 0PY London, UK b University of Oregon, Department of Anthropology, 1218 University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97403, USA c Angkor International Centre of Research and Documentation, APSARA National Authority, Siem Reap, Cambodia d Northern Illinois University, Department of Anthropology, Center for Southeast Asian Studies, 520 College View Court, IL, USA e School of Archaeology and Museology, Northwest University, Xian, Shaanxi, China f University of Hawai'i at Manoa, Department of Anthropology, HI, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The Angkorian Empire was at its peak from the 10th to 13th centuries CE. It wielded great influence across Inscriptions mainland Southeast Asia and is now one of the most archaeologically visible polities due to its expansive re- Household gardens ligious building works. This paper presents archaeobotanical evidence from two of the most renowned Non-elites Angkorian temples largely associated with kings and elites, Angkor Wat and Ta Prohm. But it focuses on the Economic crops people that dwelt within the temple enclosures, some of whom were involved in the daily functions of the Rice temple. Archaeological work indicates that temple enclosures were areas of habitation within the Angkorian Cotton urban core and the temples and their enclosures were ritual, political, social, and economic landscapes. -

Archaeology Unit Archaeology Report Series

#8 NALANDA–SRIWIJAYA CENTRE ARCHAEOLOGY UNIT ARCHAEOLOGY REPORT SERIES Tonle Snguot: Preliminary Research Results from an Angkorian Hospital Site D. KYLE LATINIS, EA DARITH, KÁROLY BELÉNYESY, AND HUNTER I. WATSON A T F Archaeology Unit 6870 0955 facebook.com/nalandasriwijayacentre Nalanda–Sriwijaya Centre ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute F W 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace, 6778 1735 Singapore 119614 www.iseas.edu.sg/centres/nalanda-sriwijaya-centre E [email protected] The Nalanda–Sriwijaya Centre Archaeology Unit (NSC AU) Archaeology Report Series has been established to provide an avenue for publishing and disseminating archaeological and related research conducted or presented within the Centre. This also includes research conducted in partnership with the Centre as well as outside submissions from fields of enquiry relevant to the Centre's goals. The overall intent is to benefit communities of interest and augment ongoing and future research. The NSC AU Archaeology Report Series is published Citations of this publication should be made in the electronically by the Nalanda–Sriwijaya Centre of following manner: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. Latinis, D. K., Ea, D., Belényesy, K., and Watson, H. I. (2018). “Tonle Snguot: Preliminary Research Results from an © Copyright is held by the author/s of each report. Angkorian Hospital Site.” Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre Archaeology Unit Archaeology Report Series No. 8. ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute accepts no responsibility for facts presented and views expressed. Responsibility Cover image: Natalie Khoo rests exclusively with the individual author or authors. Authors have agreed that permission has been obtained from appropriate sources to include any Editor : Foo Shu Tieng content in the publication such as texts, images, maps, Cover Art Template : Aaron Kao tables, charts, graphs, illustrations, and photos that are Layout & Typesetting : Foo Shu Tieng not exclusively owned or copyrighted by the authors. -

1 RESOURCES for CAMBODIAN FULBRIGHT Weavers And

RESOURCES FOR CAMBODIAN FULBRIGHT Weavers and Handicraft Author Maxwell, Robyn. Title Textiles of Southeast Asia : tradition, trade and transformation / Robyn Maxwell. Imprint Melbourne : Oxford University Press, 1990. Author Green, Gillian, curator. Title Pictorial Cambodian textiles / Gillian Green ; [editor: Narisa Chakrabongse] Imprint Bangkok : River Books ; London : Thames & Hudson [distributor], 2008. Author Green, Gillian. Title Traditional textiles of Cambodia : cultural threads and material heritage / Gillian Green. Imprint Chicago : Buppha Press, 2003. Folks and Literature Author Carrison, Muriel Paskin , 1928- Title Cambodian folk stories from the Gatiloke / retold by Muriel Paskin Carrison ; from a translation by Kong Chhean. Imprint Rutland, Vt. : C.E. Tuttle Co. , c1987. Khmer Folk Dance Paperback – March, 1987 by Sam-Ang Sam (Author), Chan Moly Sam (Author) Title Reamker (Ramakerti) : the Cambodian version of the Ramayana / translated by Judith M. Jacob with the assistance of Kuoch Haksrea. Imprint London : Royal Asiatic Society , [1986?] Author Carrison, Muriel Paskin , 1928- 1 Title Cambodian folk stories from the Gatiloke / retold by Muriel Paskin Carrison ; from a translation by Kong Chhean. Imprint Rutland, Vt. : C.E. Tuttle Co. , c1987. Arts and Paintings Title: KBACH: A Study of Khmer Ornament Alternative Title: Drawings and Photographs by Chan Vitharin Author/s: Vitharin CHAN, Preap Chanmara Editor/s: Daravuth LY, Ingrid MUAN Publisher/s: Reyum Publishing , Phnom Penh, Cambodia Year of Publication: 2005 Author Roveda, Vittorio. Title Preah bot : Buddhist painted scrolls in Cambodia / Vittorio Roveda & Sothon Yem. Imprint Bangkok : River Books, c2010. Author Roveda, Vittorio. Title Buddhist painting in Cambodia / Vittorio Roveda, Sothon Yem. Imprint Bangkok, Thailand : River Books : Holcim, 2009. Author Vann Nath, 1946- Title A Cambodian prison portrait : one year in the Khmer Rouge's S- 21 / Vann Nath ; translated by Moeun Chhean Narridh.