Teaching the Silk Road

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eastern and Western Look at the History of the Silk Road

Journal of Critical Reviews ISSN- 2394-5125 Vol 7, Issue 9, 2020 EASTERN AND WESTERN LOOK AT THE HISTORY OF THE SILK ROAD Kobzeva Olga1, Siddikov Ravshan2, Doroshenko Tatyana3, Atadjanova Sayora4, Ktaybekov Salamat5 1Professor, Doctor of Historical Sciences, National University of Uzbekistan named after Mirzo Ulugbek, Tashkent, Uzbekistan. [email protected] 2Docent, Candidate of historical Sciences, National University of Uzbekistan named after Mirzo Ulugbek, Tashkent, Uzbekistan. [email protected] 3Docent, Candidate of Historical Sciences, National University of Uzbekistan named after Mirzo Ulugbek, Tashkent, Uzbekistan. [email protected] 4Docent, Candidate of Historical Sciences, National University of Uzbekistan named after Mirzo Ulugbek, Tashkent, Uzbekistan. [email protected] 5Lecturer at the History faculty, National University of Uzbekistan named after Mirzo Ulugbek, Tashkent, Uzbekistan. [email protected] Received: 17.03.2020 Revised: 02.04.2020 Accepted: 11.05.2020 Abstract This article discusses the eastern and western views of the Great Silk Road as well as the works of scientists who studied the Great Silk Road. The main direction goes to the historiography of the Great Silk Road of 19-21 centuries. Keywords: Great Silk Road, Silk, East, West, China, Historiography, Zhang Qian, Sogdians, Trade and etc. © 2020 by Advance Scientific Research. This is an open-access article under the CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.31838/jcr.07.09.17 INTRODUCTION another temple in Suzhou, sacrifices are offered so-called to the The historiography of the Great Silk Road has thousands of “Yellow Emperor”, who according to a legend, with the help of 12 articles, monographs, essays, and other kinds of investigations. -

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia. A bibliography of historical and modern texts with introduction and partial annotation, and some echoes in Western countries. [This annotated bibliography of 220 items suggests the range and major themes of how Buddhism and people influenced by Buddhism have responded to disability in Asia through two millennia, with cultural background. Titles of the materials may be skimmed through in an hour, or the titles and annotations read in a day. The works listed might take half a year to find and read.] M. Miles (compiler and annotator) West Midlands, UK. November 2013 Available at: http://www.independentliving.org/miles2014a and http://cirrie.buffalo.edu/bibliography/buddhism/index.php Some terms used in this bibliography Buddhist terms and people. Buddhism, Bouddhisme, Buddhismus, suffering, compassion, caring response, loving kindness, dharma, dukkha, evil, heaven, hell, ignorance, impermanence, kamma, karma, karuna, metta, noble truths, eightfold path, rebirth, reincarnation, soul, spirit, spirituality, transcendent, self, attachment, clinging, delusion, grasping, buddha, bodhisatta, nirvana; bhikkhu, bhikksu, bhikkhuni, samgha, sangha, monastery, refuge, sutra, sutta, bonze, friar, biwa hoshi, priest, monk, nun, alms, begging; healing, therapy, mindfulness, meditation, Gautama, Gotama, Maitreya, Shakyamuni, Siddhartha, Tathagata, Amida, Amita, Amitabha, Atisha, Avalokiteshvara, Guanyin, Kannon, Kuan-yin, Kukai, Samantabhadra, Santideva, Asoka, Bhaddiya, Khujjuttara, -

Opening Essential Questions? Lesson Objectives

Silk Road Curriculum Project 2018-2019 Ingrid Herskind Title of Lesson Plan: Silk Road: Cartography and Trade in Ancient and Modern China Ingrid Herskind, Flintridge Prep School, La Canada, CA Lesson Overview: Students will explore the “Silk Road” trade networks by investigating a route, mapping the best path, and portraying a character who navigated the route. Opening essential questions? How did the Silk Road routes represent an early version of worldwide integration and development? How does China’s modern One Belt, One Road project use similar routes and methodologies as the earlier Silk Road project? How is this modern project different? Lesson Objectives: Students will be able to: Students will also apply skills from the Global Competence Matrix and will: • Investigate the world beyond their immediate environment by identifying an issue, generating a question, and explaining its significance locally, regionally, and globally. • Recognize their own and others’ perspectives by understanding the influences that impact those perspectives. • Communicate their ideas effectively with diverse audiences by realizing how their ideas and delivery can be perceived. • Translate their ideas and findings into appropriate actions to improve conditions and to create opportunities for personal and collaborative action. 1 1 World Savvy, Global Competence Matrix, Council of Chief State School Officers’ EdSteps Project in partnership with the Asia Society Partnership for Global Learning, 2010 1 Silk Road Curriculum Project 2018-2019 Ingrid Herskind Length of Project: This lesson as designed to take place over 2-3 days (periods are either 45 min or 77 min) in 9th Grade World History. Grade Level: High School (gr 9) World History, variation in International Relations 12th grade Historical Context: • China was a key player in the networks that crossed from one continent to another. -

A Abbasid Caliphate, 239 Relations Between Tang Dynasty China And

INDEX A anti-communist forces, 2 Abbasid Caliphate, 239 Antony, Robert, 200 relations between Tang Dynasty “Apollonian” culture, 355 China and, 240 archaeological research in Southeast Yang Liangyao’s embassy to, Asia, 43, 44, 70 242–43, 261 aromatic resins, 233 Zhenyuan era (785–805), 242, aromatic timbers, 230 256 Arrayed Tales aboriginal settlements, 175–76 (The Arrayed Tales of Collected Abramson, Marc, 81 Oddities from South of the Abu Luoba ( · ), 239 Passes Lĩnh Nam chích quái liệt aconite, 284 truyện), 161–62 Agai ( ), Princess, 269, 286 becoming traditions, 183–88 Age of Exploration, 360–61 categorizing stories, 163 agricultural migrations, 325 fox essence in, 173–74 Amarapura Guanyin Temple, 314n58 and history, 165–70 An Dương Vương (also importance of, 164–65 known as Thục Phán ), 50, othering savages, 170–79 165, 167 promotion of, 164–65 Angkor, 61, 62 savage tales, 179–83 Cham naval attack on, 153 stories in, 162–63 Angkor Wat, 151 versions of, 170 carvings in, 153 writing style, 164 Anglo-Burmese War, 294 Atwill, David, 327 Annan tuzhi [Treatise and Âu Lạc Maps of Annan], 205 kingdom, 49–51 anti-colonial movements, 2 polity, 50 371 15 ImperialChinaIndexIT.indd 371 3/7/15 11:53 am 372 Index B Biography of Hua Guan Suo (Hua Bạch Đằng River, 204 Guan Suo zhuan ), 317 Bà Lộ Savages (Bà Lộ man ), black clothing, 95 177–79 Blakeley, Barry B., 347 Ba Min tongzhi , 118, bLo sbyong glegs bam (The Book of 121–22 Mind Training), 283 baneful spirits, in medieval China, Blumea balsamifera, 216, 220 143 boat competitions, 144 Banteay Chhmar carvings, 151, 153 in southern Chinese local Baoqing siming zhi , traditions, 149 224–25, 231 boat racing, 155, 156. -

The Opening of the Silk Road 161

'T GLOBAL CONTACTS: THE OPENING 25 OF THE SILK ROAD During the early Han dynasty (206 B.cE.-220 CE.) Chinese emperors began to send large amounts of silk-for both diplomatic and commercial reasons-to the nomads of Central Asia, especially the Xiongnu. Within a short time some of this silk found its way, by means of a type of relay trade, to Rome. Modern scholars refer to the East- West routes on which the fabric, and other commodities, moved as the Silk Road. By 100 CE. the land routes linking China to Rome also had a maritime counterpart. Seaborne commerce flourished between Rome and India via the Red Sea and the Ara- bian Sea. Other routes farther east, connected Indian ports with harbors in Southeast Asia and China. A great Afro-Eurasian commercial network had now come into being. Silk from China (the only country that produced it until after 500 CE.), pepper and jewels from India, and incense from Arabia were sent to the Mediterranean region on routes that ter- minated in Roman cities such as Alexandria, Gaza, Antioch, and Ephesus. In exchange for the precious commodities, the Romans sent large amounts of silver and gold east- ward to destinations in Asia. Because the long-distance trade of the classical period was mainly in luxuries rather than in articles of daily use, its overall economic impact was probably limited. Most present-day historians think that the Rome-India-China trade was significant pri- marily because of its role in promoting the spread of religions, styles of art, technologies, and epidemic diseases. -

The Opening of the Silk Road

,~ GLOBAL CONTACTS: THE OPENING 25 OF THE SILK ROAD , . During the early Han dynasty (206 B.C.E,-220 C.E.)Chinese emperors began to send large amounts of silk-for both diplomatic and commercial reasons-to the nomads of Central Asia, especially the Xiongnu. Within a short time some of this silk found its way, by means of a type of relay trade, to Rome. Modern scholars refer to the East- West routes on which the fabric, and other commodities, moved as the Silk Road. By 100 C.E.the land routes linking China to Rome also had "a maritime counterpart. Seaborne commerce flourished between Rome and India via the Red Sea and the Ara- bian Sea. Other routes farther east, connected Indian ports with harbors in Southeast Asia and China. A great Afro-Eurasian commercial network had now come into being. Silk from China (the only country that produced it until after 500 CE.), pepper and jewels from India, and incense from Arabia were sent to the Mediterranean region on routes that ter-' minated in Roman cities such as Alexandria, Gaza, Antioch, and Ephesus. In exchange for the precious commodities, the Romans sent large amounts of silver and gold east- ward to destinations in Asia. Because the long-distance trade of the classical period was mainly in luxuries rather than in articles of daily use, its overall economic impact was probably limited. Most present-day historians think that the Rome-India-China trade was significant pri- '"", ",' ~. marily becauseof its role in promoting the spreadof religions, styles of art, technologies, and epidemic diseases. -

A STUDY of the NAMES of MONUMENTS in ANGKOR (Cambodia)

A STUDY OF THE NAMES OF MONUMENTS IN ANGKOR (Cambodia) NHIM Sotheavin Sophia Asia Center for Research and Human Development, Sophia University Introduction This article aims at clarifying the concept of Khmer culture by specifically explaining the meanings of the names of the monuments in Angkor, names that have existed within the Khmer cultural community.1 Many works on Angkor history have been researched in different fields, such as the evolution of arts and architecture, through a systematic analysis of monuments and archaeological excavation analysis, and the most crucial are based on Cambodian epigraphy. My work however is meant to shed light on Angkor cultural history by studying the names of the monuments, and I intend to do so by searching for the original names that are found in ancient and middle period inscriptions, as well as those appearing in the oral tradition. This study also seeks to undertake a thorough verification of the condition and shape of the monuments, as well as the mode of affixation of names for them by the local inhabitants. I also wish to focus on certain crucial errors, as well as the insufficiency of earlier studies on the subject. To begin with, the books written in foreign languages often have mistakes in the vocabulary involved in the etymology of Khmer temples. Some researchers are not very familiar with the Khmer language, and besides, they might not have visited the site very often, or possibly also they did not pay too much attention to the oral tradition related to these ruins, a tradition that might be known to the village elders. -

BUDDHISM (Statue of Buddha) This Statue, Dating to the Year 338 C

BUDDHISM (Statue of Buddha) This statue, dating to the year 338 C. E., is the earliest known depiction of a Chinese Buddha. Buddhism, which originated in India during the fifth century B.C.E, was gradually introduced into China through Central Asia via the Silk Road. Buddhism, which entered China during the Han dynasty, was influenced by other religions that were present in Central Asia at that time. Once in China, Buddhism was combined, for a time, with another popular Chinese belief system, Daoism. In fact, until the end of the Han dynasty, the two belief systems were virtually one and shared many beliefs. The early statues of Chinese Buddhas resembled the statues of Indian Buddhas from the fourth to fifth centuries B.C.E., but have some different features. For example, the Buddha pictured here has a more rounded head than his Indian counterpart; his nose is sculpted as a simple wedge; and his eyes, which are closed, look Chinese. TRANSPORTATION (Camel Figurine) This twin-humped camel was introduced into China from Bactria (BOK-tree-ah), in southwestern Asia, sometime around the first century B.C.E. As trade along the Silk Road grew, these pack animals became greatly valued for their ability to travel long distances over mountains and across deserts. Camels were uniquely suited to crossing the roughest terrain in an extremely difficult climate because they could go for days without food or water by living off the fat stored in their humps. Chinese traders used camels to transport such goods as silk, jade, tea, spices, and grain to the West. -

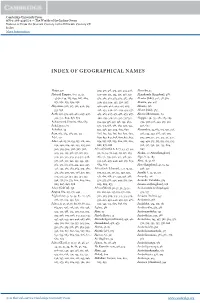

Index of Geographical Names

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42465-3 — The Worlds of the Indian Ocean Volume 2: From the Seventh Century to the Fifteenth Century CE Index More Information INDEX OF GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES Abaya, 571 309, 317, 318, 319, 320, 323, 328, Akumbu, 54 Abbasid Empire, 6–7, 12, 17, 329–370, 371, 374, 375, 376, 377, Alamkonda (kingdom), 488 45–70, 149, 185, 639, 667, 669, 379, 380, 382, 383, 384, 385, 389, Alaotra (lake), 401, 411, 582 671, 672, 673, 674, 676 390, 393, 394, 395, 396, 397, Alasora, 414, 427 Abyssinia, 306, 317, 322, 490, 519, 400, 401, 402, 409, 415, 425, Albania, 516 533, 656 426, 434, 440, 441, 449, 454, 457, Albert (lake), 365 Aceh, 198, 374, 425, 460, 497, 498, 463, 465, 467, 471, 478, 479, 487, Alborz Mountains, 69 503, 574, 609, 678, 679 490, 493, 519, 521, 534, 535–552, Aleppo, 149, 175, 281, 285, 293, Achaemenid Empire, 660, 665 554, 555, 556, 557, 558, 559, 569, 294, 307, 326, 443, 519, 522, Achalapura, 80 570, 575, 586, 588, 589, 590, 591, 528, 607 Achsiket, 49 592, 596, 597, 599, 603, 607, Alexandria, 53, 162, 175, 197, 208, Acre, 163, 284, 285, 311, 312 608, 611, 612, 615, 617, 620, 629, 216, 234, 247, 286, 298, 301, Adal, 451 630, 637, 647, 648, 649, 652, 653, 307, 309, 311, 312, 313, 315, 322, Aden, 46, 65, 70, 133, 157, 216, 220, 654, 657, 658, 659, 660, 661, 662, 443, 450, 515, 517, 519, 523, 525, 230, 240, 284, 291, 293, 295, 301, 668, 678, 688 526, 527, 530, 532, 533, 604, 302, 303, 304, 306, 307, 308, Africa (North), 6, 8, 17, 43, 47, 49, 607 309, 313, 315, 316, 317, 318, 319, 50, 52, 54, 70, 149, 151, 158, -

Silk Roads in History by Daniel C

The Silk Roads in History by daniel c. waugh here is an endless popular fascination with cultures and peoples, about whose identities we still know too the “Silk Roads,” the historic routes of eco- little. Many of the exchanges documented by archaeological nomic and cultural exchange across Eurasia. research were surely the result of contact between various The phrase in our own time has been used as ethnic or linguistic groups over time. The reader should keep a metaphor for Central Asian oil pipelines, and these qualifications in mind in reviewing the highlights from Tit is common advertising copy for the romantic exoticism of the history which follows. expensive adventure travel. One would think that, in the cen- tury and a third since the German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen coined the term to describe what for him was a The Beginnings quite specific route of east-west trade some 2,000 years ago, there might be some consensus as to what and when the Silk Among the most exciting archaeological discoveries of the Roads were. Yet, as the Penn Museum exhibition of Silk Road 20th century were the frozen tombs of the nomadic pastoral- artifacts demonstrates, we are still learning about that history, ists who occupied the Altai mountain region around Pazyryk and many aspects of it are subject to vigorous scholarly debate. in southern Siberia in the middle of the 1st millennium BCE. Most today would agree that Richthofen’s original concept These horsemen have been identified with the Scythians who was too limited in that he was concerned first of all about the dominated the steppes from Eastern Europe to Mongolia. -

The Khmer Did Not Live by Rice Alone Archaeobotanical Investigations At

Archaeological Research in Asia 24 (2020) 100213 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Archaeological Research in Asia journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ara The Khmer did not live by rice alone: Archaeobotanical investigations at Angkor Wat and Ta Prohm T ⁎ Cristina Cobo Castilloa, , Alison Carterb, Eleanor Kingwell-Banhama, Yijie Zhuanga, Alison Weisskopfa, Rachna Chhayc, Piphal Hengd,f, Dorian Q. Fullera,e, Miriam Starkf a University College London, Institute of Archaeology, 31–34 Gordon Square, WC1H 0PY London, UK b University of Oregon, Department of Anthropology, 1218 University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97403, USA c Angkor International Centre of Research and Documentation, APSARA National Authority, Siem Reap, Cambodia d Northern Illinois University, Department of Anthropology, Center for Southeast Asian Studies, 520 College View Court, IL, USA e School of Archaeology and Museology, Northwest University, Xian, Shaanxi, China f University of Hawai'i at Manoa, Department of Anthropology, HI, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The Angkorian Empire was at its peak from the 10th to 13th centuries CE. It wielded great influence across Inscriptions mainland Southeast Asia and is now one of the most archaeologically visible polities due to its expansive re- Household gardens ligious building works. This paper presents archaeobotanical evidence from two of the most renowned Non-elites Angkorian temples largely associated with kings and elites, Angkor Wat and Ta Prohm. But it focuses on the Economic crops people that dwelt within the temple enclosures, some of whom were involved in the daily functions of the Rice temple. Archaeological work indicates that temple enclosures were areas of habitation within the Angkorian Cotton urban core and the temples and their enclosures were ritual, political, social, and economic landscapes. -

Archaeology Unit Archaeology Report Series

#8 NALANDA–SRIWIJAYA CENTRE ARCHAEOLOGY UNIT ARCHAEOLOGY REPORT SERIES Tonle Snguot: Preliminary Research Results from an Angkorian Hospital Site D. KYLE LATINIS, EA DARITH, KÁROLY BELÉNYESY, AND HUNTER I. WATSON A T F Archaeology Unit 6870 0955 facebook.com/nalandasriwijayacentre Nalanda–Sriwijaya Centre ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute F W 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace, 6778 1735 Singapore 119614 www.iseas.edu.sg/centres/nalanda-sriwijaya-centre E [email protected] The Nalanda–Sriwijaya Centre Archaeology Unit (NSC AU) Archaeology Report Series has been established to provide an avenue for publishing and disseminating archaeological and related research conducted or presented within the Centre. This also includes research conducted in partnership with the Centre as well as outside submissions from fields of enquiry relevant to the Centre's goals. The overall intent is to benefit communities of interest and augment ongoing and future research. The NSC AU Archaeology Report Series is published Citations of this publication should be made in the electronically by the Nalanda–Sriwijaya Centre of following manner: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. Latinis, D. K., Ea, D., Belényesy, K., and Watson, H. I. (2018). “Tonle Snguot: Preliminary Research Results from an © Copyright is held by the author/s of each report. Angkorian Hospital Site.” Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre Archaeology Unit Archaeology Report Series No. 8. ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute accepts no responsibility for facts presented and views expressed. Responsibility Cover image: Natalie Khoo rests exclusively with the individual author or authors. Authors have agreed that permission has been obtained from appropriate sources to include any Editor : Foo Shu Tieng content in the publication such as texts, images, maps, Cover Art Template : Aaron Kao tables, charts, graphs, illustrations, and photos that are Layout & Typesetting : Foo Shu Tieng not exclusively owned or copyrighted by the authors.