Silk Roads in History by Daniel C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

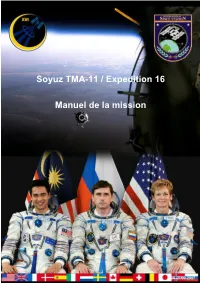

Soyuz TMA-11 / Expedition 16 Manuel De La Mission

Soyuz TMA-11 / Expedition 16 Manuel de la mission SOYUZ TMA-11 – EXPEDITION 16 Par Philippe VOLVERT SOMMAIRE I. Présentation des équipages II. Présentation de la mission III. Présentation du vaisseau Soyuz IV. Précédents équipages de l’ISS V. Chronologie de lancement VI. Procédures d’amarrage VII. Procédures de retour VIII. Horaires IX. Sources A noter que toutes les heures présentes dans ce dossier sont en heure GMT. I. PRESENTATION DES EQUIPAGES Equipage Expedition 15 Fyodor YURCHIKHIN (commandant ISS) Lieu et Lieu et date de naissance : 03/01/1959 ; Batumi (Géorgie) Statut familial : Marié et 2 enfants Etudes : Graduat d’économie à la Moscow Service State University Statut professionnel: Ingénieur et travaille depuis 1993 chez RKKE Roskosmos : Sélectionné le 28/07/1997 (RKKE-13) Précédents vols : STS-112 (07/10/2002 au 18/10/2002), totalisant 10 jours 19h58 Oleg KOTOV(ingénieur de bord) Lieu et date de naissance : 27/10/1965 ; Simferopol (Ukraine) Statut familial : Marié et 2 enfants Etudes : Doctorat en médecine obtenu à la Sergei M. Kirov Military Medicine Academy Statut professionnel: Colonel, Russian Air Force et travaille au centre d’entraînement des cosmonautes, le TsPK Roskosmos : Sélectionné le 09/02/1996 (RKKE-12) Précédents vols : - Clayton Conrad ANDERSON (Ingénieur de vol ISS) Lieu et date de naissance : 23/02/1959 ; Omaha (Nebraska) Statut familial : Marié et 2 enfants Etudes : Promu bachelier en physique à Hastings College, maîtrise en ingénierie aérospatiale à la Iowa State University Statut professionnel: Directeur du centre des opérations de secours à la Nasa Nasa : Sélectionné le 04/06/1998 (Groupe) Précédents vols : - Equipage Expedition 16 / Soyuz TM-11 Peggy A. -

Two Great Adventurers, Battuta and Polo, Affect the Medieval World

Two Great Adventurers, Battuta and Polo, Affect the Medieval World When you take a trip, how do you record what you did? Do you take pictures, and maybe post some of them on a social media site? Or you do send postcards or emails to your family and friends about your travels? Do you keep a journal to record events as they happen? Ibn Battuta and Marco Polo traveled in a time around the 13th and 14th centuries when recording events was not as easy as it is today. Upon their return to their homes, both Ibn Battuta and Marco Polo wrote about their adventures. Their stories were very influential in stimulating trade and travel in the regions they visited. Ibn Battuta’s desire to see the lands where his fellow Muslims lived led him across Asia, Africa, and Europe and the seas. His nearly thirty years of travel began when he was twenty-one when he set off for a pilgrimage to Mecca. After that, he traveled over 75,000 miles. Ibn Battuta traveled by joining trading caravans. Caravans were bands of travelers who journeyed together for security and mutual aid. He told of his adventures when he returned home to Morocco, and those who heard his stories thought they should be written down. The sultan of Morocco commissioned a young court secretary named Ibn Juzayy to listen to Ibn Battuta’s stories and record them. It took two years to write everything down, and when they were finished, the result was the Rihla, a story of travels centered on a pilgrimage. -

Parent Memo-26 |

Dear Parent, Hope you are well, As part of our Science and Technology Week, we are pleased to inform you that we will be hosting special events and activities for all students. One of the highlighted activities is a visit by a special guest speaker, Astronaut Nicole Stott. Nicole Stott is an American engineer and a retired NASA astronaut. She worked for NASA for 27 years in various positions and is one of very few women who conducted a spacewalk. Astronaut Stott served as a Flight Engineer on ISS Expedition 20 and Expedition 21 and was a Mission Specialist on STS-128 and STS-133. Please find attached her biography which denotes her very impressive career as an engineer, astronaut and director of missions. Nicole is the first person to tweet from space, and is an artist who has created several paintings while in space. She represents a perfect example of why we believe art must be integrated into the world of STEM to inspire creativity and innovation. This celebrated astronaut will be interacting with all of our students virtually starting May 3rd until May 6th 2020. Please find below the scheduled visits: Grade Date / Time Grades 5 and 6 Sunday, May 3rd at 1:00 p.m. Grades 7 and 8 Monday, May 4th at 1:00 p.m. Grades 9 and 10 Tuesday, May 5th at 1:00 p.m. Grades 11 and 12 Wednesday, May 6th at 1:00 p.m. Zoom Meeting IDs will be emailed to all students the night before. Each class will submit questions to the teachers beforehand and 6 of the best questions will be asked in the session to be answered by Astronaut Stott. -

The Silk Roads: an ICOMOS Thematic Study

The Silk Roads: an ICOMOS Thematic Study by Tim Williams on behalf of ICOMOS 2014 The Silk Roads An ICOMOS Thematic Study by Tim Williams on behalf of ICOMOS 2014 International Council of Monuments and Sites 11 rue du Séminaire de Conflans 94220 Charenton-le-Pont FRANCE ISBN 978-2-918086-12-3 © ICOMOS All rights reserved Contents STATES PARTIES COVERED BY THIS STUDY ......................................................................... X ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................................... XI 1 CONTEXT FOR THIS THEMATIC STUDY ........................................................................ 1 1.1 The purpose of the study ......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Background to this study ......................................................................................................... 2 1.2.1 Global Strategy ................................................................................................................................ 2 1.2.2 Cultural routes ................................................................................................................................. 2 1.2.3 Serial transnational World Heritage nominations of the Silk Roads .................................................. 3 1.2.4 Ittingen expert meeting 2010 ........................................................................................................... 3 2 THE SILK ROADS: BACKGROUND, DEFINITIONS -

Changes in Wheat Starch Grains Using Different Cooking Methods: Insights

December 2013 Vol.58 Suppl. : 8289 Ⅰ 《中国科学》杂志社 www.scichina.com csb.scichina.com SCIENCE CHINA PRESS Article Changes in wheat starch grains using different cooking methods: Insights into ancient food processing techniques DAI Ji1,2, YANG YiMin1,2 , WANG Bo3, WANG ChangSui1,2 & JIANG HongEn1,2* 1 Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100044, China; 2 Department of Scientific History and Archaeometry, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China; 3 Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Museum, Urumqi 830006, China *Corresponding author (email: [email protected]) Received April 11, 2013; accepted August 8, 2013 We investigate the morphological changes in starch grains from wheat (Triticum aestivum) using different cooking methods (boiling, steaming, frying, and baking). We compare the cooked starch grains with starch grains from ancient wheat flour cakes (Astana Cemetery, Turpan Basin, Xinjiang, China) to determine the cooking techniques used by people in Xinjiang 1200 years ago. Heat and water content affect starch grains when different cooking methods are used. Boiling and steaming results in the collapse of wheat starch grains accompanied by extreme swelling, curved granules, pasting, almost full gelatinization, a distinct extinction cross and vague granule outlines. Frying and baking cause less swelling, fewer curved granules, less pasting and only partial gelatinization of wheat starch grains, but the extinction lines are still distinct and the outlines of granules relatively clear. The pale brown substances on the starch grains make starch from baked-wheat products distinct from those cooked using other methods. -

Empires in East Asia

DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=NL-C Module 3 Empires in East Asia Essential Question In general, was China helpful or harmful to the development of neighboring empires and kingdoms? About the Photo: Angkor Wat was built in In this module you will learn how the cultures of East Asia influenced one the 1100s in the Khmer Empire, in what is another, as belief systems and ideas spread through both peaceful and now Cambodia. This enormous temple was violent means. dedicated to the Hindu god Vishnu. What You Will Learn … Explore ONLINE! Lesson 1: Tang and Song China . 80 The Big Idea During the Tang and Song dynasties, China experienced VIDEOS, including... an era of prosperity and technological innovation. • A Mongol Empire in China Lesson 2: The Mongols . 90 • Ancient Discoveries: Chinese Warfare The Big Idea The Mongols, a nomadic people from the steppe, • Ancient China: Masters of the Wind conquered settled societies across much of Asia and established the and Waves Yuan Dynasty to rule China. • Marco Polo: Journey to the East Lesson 3: Korean Dynasties . 100 The Big Idea The Koreans adapted Chinese culture to fi t their own • Rise of the Samurai Class needs but maintained a distinct way of life. • How the Vietnamese Defeated Lesson 4: Feudal Powers in Japan. 104 the Mongols The Big Idea Japanese civilization was shaped by cultural borrowing • Lost Spirits of Cambodia from China and the rise of feudalism and military rulers. Lesson 5: Kingdoms of Southeast Asia . 110 The Big Idea Several smaller kingdoms prospered in Southeast Asia, Document-Based Investigations a region culturally infl uenced by China and India. -

Chronology of Chinese History

Chronology of Chinese History I. Prehistory Neolithic Period ca. 8000-2000 BCE Xia (Hsia)? Trad. 2200-1766 BCE II. The Classical Age (Ancient China) Shang Dynasty ca. 1600-1045 BCE (Trad. 1766-1122 BCE) Zhou (Chou) Dynasty ca. 1045-256 BCE (Trad. 1122-256 BCE) Western Zhou (Chou) ca. 1045-771 BCE Eastern Zhou (Chou) 770-256 BCE Spring and Autumn Period 722-468 BCE (770-404 BCE) Warring States Period 403-221 BCE III. The Imperial Era (Imperial China) Qin (Ch’in) Dynasty 221-207 BCE Han Dynasty 202 BCE-220 CE Western (or Former) Han Dynasty 202 BCE-9 CE Xin (Hsin) Dynasty 9-23 Eastern (or Later) Han Dynasty 25-220 1st Period of Division 220-589 The Three Kingdoms 220-265 Shu 221-263 Wei 220-265 Wu 222-280 Jin (Chin) Dynasty 265-420 Western Jin (Chin) 265-317 Eastern Jin (Chin) 317-420 Southern Dynasties 420-589 Former (or Liu) Song (Sung) 420-479 Southern Qi (Ch’i) 479-502 Southern Liang 502-557 Southern Chen (Ch’en) 557-589 Northern Dynasties 317-589 Sixteen Kingdoms 317-386 NW Dynasties Former Liang 314-376, Chinese/Gansu Later Liang 386-403, Di/Gansu S. Liang 397-414, Xianbei/Gansu W. Liang 400-422, Chinese/Gansu N. Liang 398-439, Xiongnu?/Gansu North Central Dynasties Chang Han 304-347, Di/Hebei Former Zhao (Chao) 304-329, Xiongnu/Shanxi Later Zhao (Chao) 319-351, Jie/Hebei W. Qin (Ch’in) 365-431, Xianbei/Gansu & Shaanxi Former Qin (Ch’in) 349-394, Di/Shaanxi Later Qin (Ch’in) 384-417, Qiang/Shaanxi Xia (Hsia) 407-431, Xiongnu/Shaanxi Northeast Dynasties Former Yan (Yen) 333-370, Xianbei/Hebei Later Yan (Yen) 384-409, Xianbei/Hebei S. -

Inheritance, Protection and Innovative Development of China's Intangible Cultural Heritage—Carved Lacquerware

https://doi.org/10.37420/icaces.2020.031 Inheritance, Protection and Innovative Development of China's Intangible Cultural Heritage—Carved Lacquerware Desai Jiang, Yue Xu College of Arts, Guilin University of Technology, Guilin 541006, China Abstract: This paper studies the protection and inheritance of this precious China’s intangible cultural heritage from the aspects of carving lacquer technology, personnel training and innovation. Focusing on the protection of carving lacquer technology and the innovation in the design and production of carved lacquer handicrafts, it is proposed to protect the carving lacquer technology from three aspects which is intellectual property right, personnel training and raw material. In terms of technical innovation, the possibility of combining carved lacquer with various materials is studied and analyzed. Keywords: Carved lacquer; Arts and crafts; Lacquerware; Intangible cultural heritage 1 Introduction Carved lacquer is a unique category of arts and crafts in China. It can also be called Tihong, Tihuang,Tihei,Ticai and Tixi, because of its different colors. Among them, Beijing carved lacquerware is the most representative example, and has many quality products in the world. Carved lacquer has a long history. According to records, it can be traced back to the Tang Dynasty. The Yuan Dynasty carved lacquer gradually flourished, and the Ming and Qing Dynasties were its heyday of development. Carved lacquer handicrafts have won many awards in international expositions and earned a lot of foreign exchange for the country in special period. In 2006, carved lacquer was listed in the first batch of national intangible cultural heritage list in China. Unfortunately, since the 1990s, the carved lacquer industry has gradually shrunk, as the number of employees is extremely reduced and the trend is aging, cause the inheritance of skills has seriously broken down. -

CGEH Working Paper Series Urbanization in China, Ca. 1100

CGEH Working Paper Series Urbanization in China, ca. 1100–1900 Yi Xu, Guangxi Normal University and Utrecht University Bas van Leeuwen, Utrecht University and IISH Jan Luiten van Zanden, Utrecht University January 2015 Working paper no. 63 www.cgeh.nl/working-paper-series/ Urbanization in China, ca. 1100–1900 Yi Xu, Guangxi Normal University and Utrecht University Bas van Leeuwen, Utrecht University and IISH Jan Luiten van Zanden, Utrecht University Abstract: This paper presents new estimates of the development of the urban population and the urbanization ratio for the period spanning the Song and late Qing dynasties. Urbanization is viewed, as in much of the economic historical literature on the topic, as an indirect indicator of economic development and structural change. The development of the urban system can therefore tell us a lot about long-term trends in the Chinese economy between 1100 and 1900. During the Song the level of urbanization was high, also by international standards – the capital cities of the Song were probably the largest cities in the world. This remained so until the late Ming, but during the Qing there was a downward trend in the level of urbanization from 11–12% to 7% in the late 18th century, a level at which it remained until the early 1900s. In our paper we analyse the role that socio–political and economic causes played in this decline, such as the changing character of the Chinese state, the limited impact of overseas trade on the urban system, and the apparent absence of the dynamic economic effects that were characteristic for the European urban system. -

Highlights in Space 2010

International Astronautical Federation Committee on Space Research International Institute of Space Law 94 bis, Avenue de Suffren c/o CNES 94 bis, Avenue de Suffren UNITED NATIONS 75015 Paris, France 2 place Maurice Quentin 75015 Paris, France Tel: +33 1 45 67 42 60 Fax: +33 1 42 73 21 20 Tel. + 33 1 44 76 75 10 E-mail: : [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Fax. + 33 1 44 76 74 37 URL: www.iislweb.com OFFICE FOR OUTER SPACE AFFAIRS URL: www.iafastro.com E-mail: [email protected] URL : http://cosparhq.cnes.fr Highlights in Space 2010 Prepared in cooperation with the International Astronautical Federation, the Committee on Space Research and the International Institute of Space Law The United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs is responsible for promoting international cooperation in the peaceful uses of outer space and assisting developing countries in using space science and technology. United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs P. O. Box 500, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: (+43-1) 26060-4950 Fax: (+43-1) 26060-5830 E-mail: [email protected] URL: www.unoosa.org United Nations publication Printed in Austria USD 15 Sales No. E.11.I.3 ISBN 978-92-1-101236-1 ST/SPACE/57 *1180239* V.11-80239—January 2011—775 UNITED NATIONS OFFICE FOR OUTER SPACE AFFAIRS UNITED NATIONS OFFICE AT VIENNA Highlights in Space 2010 Prepared in cooperation with the International Astronautical Federation, the Committee on Space Research and the International Institute of Space Law Progress in space science, technology and applications, international cooperation and space law UNITED NATIONS New York, 2011 UniTEd NationS PUblication Sales no. -

Official Colours of Chinese Regimes: a Panchronic Philological Study with Historical Accounts of China

TRAMES, 2012, 16(66/61), 3, 237–285 OFFICIAL COLOURS OF CHINESE REGIMES: A PANCHRONIC PHILOLOGICAL STUDY WITH HISTORICAL ACCOUNTS OF CHINA Jingyi Gao Institute of the Estonian Language, University of Tartu, and Tallinn University Abstract. The paper reports a panchronic philological study on the official colours of Chinese regimes. The historical accounts of the Chinese regimes are introduced. The official colours are summarised with philological references of archaic texts. Remarkably, it has been suggested that the official colours of the most ancient regimes should be the three primitive colours: (1) white-yellow, (2) black-grue yellow, and (3) red-yellow, instead of the simple colours. There were inconsistent historical records on the official colours of the most ancient regimes because the composite colour categories had been split. It has solved the historical problem with the linguistic theory of composite colour categories. Besides, it is concluded how the official colours were determined: At first, the official colour might be naturally determined according to the substance of the ruling population. There might be three groups of people in the Far East. (1) The developed hunter gatherers with livestock preferred the white-yellow colour of milk. (2) The farmers preferred the red-yellow colour of sun and fire. (3) The herders preferred the black-grue-yellow colour of water bodies. Later, after the Han-Chinese consolidation, the official colour could be politically determined according to the main property of the five elements in Sino-metaphysics. The red colour has been predominate in China for many reasons. Keywords: colour symbolism, official colours, national colours, five elements, philology, Chinese history, Chinese language, etymology, basic colour terms DOI: 10.3176/tr.2012.3.03 1. -

Analysis of Artistic Characteristics of Chu Lacquerworks

2018 International Conference on Education, Management and Social Science (EMSS 2018) ISBN: 978-1-60595-554-4 Analysis of Artistic Characteristics of Chu Lacquerworks Han-Qing Ge Abstract: Chu lacquer has become the representative of lacquer art in the Warring States Period because of its variety and excellent production. This article elaborates its unique artistic features through the analysis of the selection, types and modeling arts, colors, decoration and other aspects of Chu lacquer ware. Keyword: Chu Lacquerware, Fetus, types and shapes, decorative techniques, patterns Chu State is a country with a long history and amazing color in Chinese history. During the Warring States period, only the Chu State could contend with the Qin State and there was a trend of being divided by the world with Qin. According to "Huainanzi • soldier slightly training" records, "South Juan Yuan Xiang, north around Ying Si, West Bao Ba Shu, East Huai Huai, Ying Ru thought , Jianghan that pool, Yuan to Deng Lin, cotton with Fangcheng, Chu's strong, the earth in public, in points world. "Thus, Chu territory was almost covered the entire southern region. At present, the construction of major provincial capital cities in central and southern China all have the credit of the Chu Kingdom. At the same time, the Chu culture has gradually infiltrated into various places. Most of the lacquer wares from the Warring States Period come from the Chu Tomb. During this period, the lacquer ware manufacturing industry entered an unprecedented prosperity stage. It is the first peak of the development of Chinese lacquer ware art. There are three reasons for this: First, Chu is located in a warm and humid subtropical region, 15 degrees Celsius temperature and 1100 mm rainfall, even if the production process of lacquer simplification, but also easy to form a high-quality film.