Changes in Wheat Starch Grains Using Different Cooking Methods: Insights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Silk Roads: an ICOMOS Thematic Study

The Silk Roads: an ICOMOS Thematic Study by Tim Williams on behalf of ICOMOS 2014 The Silk Roads An ICOMOS Thematic Study by Tim Williams on behalf of ICOMOS 2014 International Council of Monuments and Sites 11 rue du Séminaire de Conflans 94220 Charenton-le-Pont FRANCE ISBN 978-2-918086-12-3 © ICOMOS All rights reserved Contents STATES PARTIES COVERED BY THIS STUDY ......................................................................... X ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................................... XI 1 CONTEXT FOR THIS THEMATIC STUDY ........................................................................ 1 1.1 The purpose of the study ......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Background to this study ......................................................................................................... 2 1.2.1 Global Strategy ................................................................................................................................ 2 1.2.2 Cultural routes ................................................................................................................................. 2 1.2.3 Serial transnational World Heritage nominations of the Silk Roads .................................................. 3 1.2.4 Ittingen expert meeting 2010 ........................................................................................................... 3 2 THE SILK ROADS: BACKGROUND, DEFINITIONS -

A Study on the Auspicious Animal Motifs on Han Textiles in Ancient China

A STUDY ON THE AUSPICIOUS ANIMAL MOTIFS ON HAN TEXTILES IN ANCIENT CHINA Zhang Wen 張文 Xu Chunzhong 徐純中 Wu Zhuo 吳焯 Qiu Yiping 邱夷平 hinese textiles have many animal motifs, found weft ones will be from 1/3 up to nearly all of of the C especially in combination with traditional Chi- cloth width (Zhao 2005, p. 132). There are many dif- nese cloud-designs. Such textiles were manufactured ferent kinds of animals in the designs on these textiles. during the period of the Han 漢代 and Northern Dy- To begin, we will classify in the table on the next page nasties (206 BCE – 589 CE), with many of the high- all the auspicious animals on the textiles by “species,” est quality examples produced in the Eastern Han the individual pieces often identifi ed by the inscrip- period, (25 – 220 CE). In earlier research, most schol- tions on them. ars thought motifs such as the winged monster origi- All the textiles in the list represent some of the fi n- nated in Chinese traditional culture: such auspicious est examples of world textile art. Most of them were 麒麟 天祿 animals have other names, e.g., qilin , tianlu , manufactured during the period from the Han to the 辟邪 bixie . Of interest though is the fact that similar Northern and Southern Dynasties. Such silk textiles depictions have been found in other places far away have been found in different sites, evidence for Silk from China — Central Asia, Western Asia, and even Road trade across Eurasia, from Korea in the east to in ancient Greece. -

Langdon Warner at Dunhuang: What Really Happened? by Justin M

ISSN 2152-7237 (print) ISSN 2153-2060 (online) The Silk Road Volume 11 2013 Contents In Memoriam ........................................................................................................................................................... [iii] Langdon Warner at Dunhuang: What Really Happened? by Justin M. Jacobs ............................................................................................................................ 1 Metallurgy and Technology of the Hunnic Gold Hoard from Nagyszéksós, by Alessandra Giumlia-Mair ......................................................................................................... 12 New Discoveries of Rock Art in Afghanistan’s Wakhan Corridor and Pamir: A Preliminary Study, by John Mock .................................................................................................................................. 36 On the Interpretation of Certain Images on Deer Stones, by Sergei S. Miniaev ....................................................................................................................... 54 Tamgas, a Code of the Steppes. Identity Marks and Writing among the Ancient Iranians, by Niccolò Manassero .................................................................................................................... 60 Some Observations on Depictions of Early Turkic Costume, by Sergey A. Yatsenko .................................................................................................................... 70 The Relations between China and India -

半臂 a Banbi - Half-Sleeved Jacket V

半臂 A Banbi - Half-sleeved Jacket v. 2.0 for Gulf Wars in the Kingdom of An Tir March 19, 2020 AS LIV Ouyang Yingzhao A Banbi - Half-sleeved Jacket 1 Contents Contents 1 Preface 2 Introduction 3 The Banbi 4 Patterning 10 Initial Construction 14 Second Iteration 16 Initial Conclusions 17 Secondary Conclusions 17 Appendix A 18 Textiles 18 Fiber 18 Dyeing 18 Weave 19 Sewing Techniques 22 Tools 22 Stitches, Finishing Techniques, and Closures 24 Appendix B 27 Chinese Dynasties and Tang Dynasty Emperors 27 References 28 mka Marti Fuerst biblionalia.info/leah Ouyang Yingzhao A Banbi - Half-sleeved Jacket 2 Preface This is the second iteration of this project, which I initially entered in Magna Faire (AS LIV/2019). After receiving feedback, I made some adjustments to my documentation’s organization, included more information about the garment ties, and added more images to my documentation, including final images of both the first and second iteration, for comparison. On the garment, I re-made both the ties and re-stitched the inner seam of the collar with a different, more invisible stitch. Between the first and second iteration, I received the appendix to Ulrike Halbertsma-Herold’s Master’s Thesis, from Leiden University, Clothing authority: Mongol attire and textiles in the socio-political complex. This appendix included three images of extant half-sleeve outer garments which are visually similar to the Chinese banbi. I’ve added a brief discussion of these jackets based on the sources provided by Halberstma-Herold to my discussion of the banbi. In order to maintain the integrity of the first attempt, I have relabled that section Initial Construction and put additional notes and reflections under the headings Second Iteration and Secondary Conclusions. -

Silk Roads in History by Daniel C

The Silk Roads in History by daniel c. waugh here is an endless popular fascination with cultures and peoples, about whose identities we still know too the “Silk Roads,” the historic routes of eco- little. Many of the exchanges documented by archaeological nomic and cultural exchange across Eurasia. research were surely the result of contact between various The phrase in our own time has been used as ethnic or linguistic groups over time. The reader should keep a metaphor for Central Asian oil pipelines, and these qualifications in mind in reviewing the highlights from Tit is common advertising copy for the romantic exoticism of the history which follows. expensive adventure travel. One would think that, in the cen- tury and a third since the German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen coined the term to describe what for him was a The Beginnings quite specific route of east-west trade some 2,000 years ago, there might be some consensus as to what and when the Silk Among the most exciting archaeological discoveries of the Roads were. Yet, as the Penn Museum exhibition of Silk Road 20th century were the frozen tombs of the nomadic pastoral- artifacts demonstrates, we are still learning about that history, ists who occupied the Altai mountain region around Pazyryk and many aspects of it are subject to vigorous scholarly debate. in southern Siberia in the middle of the 1st millennium BCE. Most today would agree that Richthofen’s original concept These horsemen have been identified with the Scythians who was too limited in that he was concerned first of all about the dominated the steppes from Eastern Europe to Mongolia. -

Xinjiang Museum

Coordinates: 43°49′10.32″N 87°35′02.29″E Xinjiang Museum The Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region Museum, or Xinjiang Museum, is located in Urumqi, Xinjiang, China. Its Xinjiang Museum address is at 581 Xibei Road, Urumqi.[1] 物馆 The museum holds over 40,000 items of various cultural relics and specimens, including 381 national first-grade cultural relics (国 家 ⼀ 级 ⽂ 物 ). In May 2008, the Xinjiang Museum was included in the first batch of the National first-grade museums of China. Contents General Exhibits Gallery See also References External links Location Urumqi, Xinjiang, China General Coordinates 43°49′10.32″N 87°35′02.29″E The Xinjiang Museum was established in August 1959. The current museum building was built and opened for public on September 20, 2005. Exhibits The museum has been set up to show the four major exhibits: "Recover the Western Region's Glory of Yesterday - the exhibit of the historical cultural relics in Xinjiang", "the exhibit of Xinjiang's ethnic customs", "The Mummies of the Immortal World - the exhibit of the ancient mummies of Xinjiang,", “The Historical Monuments – the exhibit of Xinjiang's revolutionary history”[2]. Gallery Inside the museum An exhibit at the Fuxi and, his sister Kharosthi script Xinjiang Region and wife, Nüwa Museum Beauty of Loulan, a The life depicted on Statuette of a Greek A wooden bar mummy from Loulan the tomb wall soldier, from a 3rd- inscribed with Old (Astana Cemetery) century BCE burial Uyghur text site north of the Tian Shan See also List of museums in China Turpan Museum Hotan Cultural Museum References 1. -

Tang Dynasty Games Magna Faire, AS LIV/2019

Ouyang Yingzhao Tang Dynasty Games Magna Faire, AS LIV/2019 Weiqi (围棋) or Go A game of Strategy Perhaps better known by the name of it’s Japanese deritivie, Go, weiqi (围棋, wéi qí) is a territory control game played with a gridded board and 361 disc-shaped pieces. Unlike western Chess, there are no prescribed, piece-specific directional moves in Go, so that the combination possibilities are almost infinite. In the Tang Dynasty, one’s ability to play Go was a measure of a person’s gentility among the elites (men and women alike), along with calligraphy, music, and painting.1 The earliest reliable record of the game comes from 548 BCE, making it possibly the oldest game that has been continuously played.2 The standard size Go board consists of a grid of 19 by 19 intersections, but variant boards have existed throughout history. The earliest extant board, a fragment from the mausoleum of Emperor Jing (r. 157-141 BCE) is 17 by 17.3 Two more 17 by 17 boards were found in an Eastern Han Dynasty (dates) tomb and official Cao Teng’s tomb (mid-second century). A 15 by 15 board was found in a tomb dated to the late Western Han Dynasty, and similar variants may have survived into the Tang or Liao periods. (dates).4 The earliest 19 by 19 board is made of porcelain and dates to 595, and another is from the early Tang Dynasty, found in the tomb of Ran Rencai (598-652), who was Prefect of Yongzhou.5 To play weiqi, players take turns placing black and white stones on the board’s intersections. -

Easy, Breezy, Beautiful: Tang Ladies Fashion for Your Summer SCA Needs

Easy, Breezy, Beautiful: Tang Ladies Fashion for your Summer SCA Needs The Honorable Lady Ouyang Yingzhao • For the Known World Costume and Fiber Arts Symposium 2019 Tang Dynasty China (7th – 8th Century) fashion for court ladies featured flowing skirts and sleeves made of lightweight fabric. It’s a style that flatters a variety of body types and is incredibly comfortable. This class will go over the basic wardrobe pieces, including cutting layouts, construction, and fabric options, as well as accessories to complete the look. Table of Contents Overview 1 Introduction 1 The Tang Dynasty — A Brief History 1 Sumptuary Laws 3 Fibers and Fabrics 3 Colors and Patterning 4 General Construction Notes 5 Fabric Width 5 Seams and Finishes 5 Closures 6 Wardrobe 7 Undergarments 7 The elusive Hezi (诃子, hŭ-tzŭ) — upper undergarment 7 Debunking the “Hezi-qun” 9 Ku (袴, kū) and Kun (裈, kūn) — pants with a crotch and without a crotch 11 Wa (袜, wă) — Socks 14 Garments 15 Ru (襦, rū) — Shirt 15 Qun (裙, chūn) — Skirt 19 Banbi (半臂, băn-bī) — Jacket 22 Da Xiu Shan (大袖衫, dă shō shăn) — Large-sleeved Gown 23 Accessories 25 Pibo (披帛, pībō) and Peizi (帔子, pĕi-tzŭ) — Shawls and Capes 25 Shoes 25 Jewelry 26 Cosmetology 28 Hair, including “Adopted hair” (义髻, hē jĭ) 28 Makeup 28 Suggested Reading 30 Tang Dynasty 30 Textiles 30 Wardrobe 30 Cosmetology 30 References 31 About the Author Back OVERVIEW The Tang Dynasty — A Brief History The Tang Dynasty (唐朝, tăng) lasted from 618 to Introduction 907 CE and is widely considered the “golden age” of imperial China.1 China today covers 9.596 million This handout was written to accompany my class square miles and a variety of climates.2 Summer at Known World Costuming and Fiber Arts Sympo- temperatures ranged from 115 degrees3 in Turpan, sium in June 2019. -

Notes on the Lighting Devices in the Medicine Buddha Transformation Tableau in Mogao Cave 220, Dunhuang by Sha Wutian 沙武田

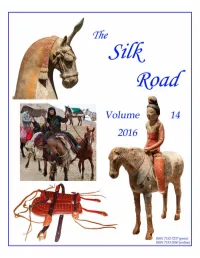

ISSN 2152-7237 (print) ISSN 2153-2060 (online) The Silk Road Volume 14 2016 Contents From the editor’s desktop: The Future of The Silk Road ....................................................................... [iii] Reconstruction of a Scythian Saddle from Pazyryk Barrow № 3 by Elena V. Stepanova .............................................................................................................. 1 An Image of Nighttime Music and Dance in Tang Chang’an: Notes on the Lighting Devices in the Medicine Buddha Transformation Tableau in Mogao Cave 220, Dunhuang by Sha Wutian 沙武田 ................................................................................................................ 19 The Results of the Excavation of the Yihe-Nur Cemetery in Zhengxiangbai Banner (2012-2014) by Chen Yongzhi 陈永志, Song Guodong 宋国栋, and Ma Yan 马艳 .................................. 42 Art and Religious Beliefs of Kangju: Evidence from an Anthropomorphic Image Found in the Ugam Valley (Southern Kazakhstan) by Aleksandr Podushkin .......................................................................................................... 58 Observations on the Rock Reliefs at Taq-i Bustan: A Late Sasanian Monument along the “Silk Road” by Matteo Compareti ................................................................................................................ 71 Sino-Iranian Textile Patterns in Trans-Himalayan Areas by Mariachiara Gasparini ....................................................................................................... -

A Mathematic Expression of Art: Sino- Iranian and Uighur Textile Interactions and the Turfan Textile Collection in Berlin

134 A Mathematic Expression of Art A Mathematic Expression of Art: Sino- Iranian and Uighur Textile Interactions and the Turfan Textile Collection in Berlin Mariachiara Gasparini, Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Introduction The two main roads around the Tarim Basin in Xinjiang province, China, are commonly referred to as the Northern and Southern Silk Road. Along them once thrived important cities and sacred places, where different artistic influences from various Central Asian cultures had gathered. The northern road, along which the city of Turfan is located, transversed one of the main cross-cultural regions between East and West, which can be defined as Sogdian-Turfanese. It reaches from the city of Samarkand in present Uzbekistan to the area of Dunhuang in Gansu province, China (figure 1).1 Indian, Iranian, Chinese, Turkic and Mongolian Tibetan populations, along with diasporas from small and big heterogeneous ethnic groups, which over the centuries had moved in many directions along the Silk Road network, were among those who created a style that, due to its multi-ethnical features, should be recognized as “Central Asian”. Nevertheless, this term has still not found its rightful place in the history of art. Instead, the style has been labeled as “Chinese”, or sometimes “Iranian”, or “Indian” depending on the scholarly discipline of the studies. However, in the Sogdian-Turfanese context, where languages and religions belonging to western, eastern, northern, and southern regions coalesced, the collaboration of local artisans who emerged from this cultural melting pot made a distinctly Central Asian style recognizable and different from those of the metropolitan and central areas of the great Chinese, Iranian or Indian empires. -

Identification of Cannabis Fiber from the Astana Cemeteries, Xinjiang, China, with Reference to Its Unique Decorative Utilization1

Identification of Cannabis Fiber from the Astana Cemeteries, Xinjiang, China, with Reference to Its Unique Decorative Utilization1 2,3 4 5 2,3 2,3 TAO CHEN ,SHUWEN YAO ,MARK MERLIN ,HUIJUAN MAI ,ZHENWEI QIU , 3,2 4 3,2 ,3,2 YAOWU HU ,BO WANG ,CHANGSUI WANG , AND HONGEN JIANG* 2Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China 3Department of Scientific History and Archaeometry, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China 4Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Museum, Urumchi, China 5University of Hawai‘i at Manoa, Honolulu, HI, USA *Corresponding author; e-mail: [email protected] Identification of Cannabis Fiber from the Astana Cemeteries, Xinjiang, China, with Reference to Its Unique Decorative Utilization: In the Turpan District of Xinjiang, China, large numbers of ancient clay figurines, with representations including equestrians, animals, and actors, have been excavated from the Astana Cemeteries and date from about the 3rd to the 9th centuries C.E. Based on visual inspection, the tails of some of the figurines representing horses are made of plant fibers. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, light microscope examination, and drying–twist tests demonstrated that these fibers were extracted from one or more stalks of hemp (Cannabis) plants. This is a unique report of the utilization of Cannabis bast fibers for figurine decoration in ancient Turpan. 阿斯塔那古墓群出土大麻纤维的鉴定分析及其装饰功能的探讨. 中国新疆吐鲁番地区阿斯塔 那古墓群出土了大量年代为公元3–9世纪的泥俑,其中包括骑马俑,动物俑和演员俑等。肉 眼观察发现骑马俑的马尾可能由植物纤维制成。通过傅里叶变换红外光谱、光学显微镜观 察和纤维旋转方向实验鉴定出这些植物纤维来自于大麻纤维。这一发现为我们提供了吐鲁 番先民利用大麻纤维装饰泥俑的新证据。 Key Words: Cannabis, fiber plant, Astana Cemeteries, clay figurines, ethnobotany. Introduction remains, and food residues (Chen et al. -

](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8715/download-english-pdf-5188715.webp)

Download[English](PDF)

31 Eurasian Transfer of Knowledge vs. Eurasian Interchange of Knowledge ―The Times Before Writing― Alfons LABISCH* Abstract/Summary In light of the widely discussed issues on the modernization and indus- trialization of East Asia, it is sometimes overlooked that there has been a constant exchange of knowledge between East Asia and Europe. This “transfer of knowledge” during all known times was associated with the traffic of humans, animals and goods and had an input on skills and tech- niques, too. And it were not only goods, skills and knowledge, but religions, world views and cultures that were exchanged. Thus is it productive to speak of an “transfer of knowledge”? Is it not rather productive to speak of a constant exchange and thus of an “inter- change of knowledge” - and so of a steadily ongoing process of giving and taking? So is the real question what separates East Asia and Europe or what they have in common? It is precisely this general problem that is to be pursued in a special question in time, for which there are no written sources. So it is about the earliest history, possibly even the origin of exchange processes between East and West, which can be achieved with most modern methods. Are the latest methods and results of archeology providing us with information on whether, as of when and in what areas, an exchange of knowledge between East and West existed before the time of writing? This question is being examined in a central region of the exchange, namely the “Oasis Silk Road” with the “bottle neck” of the Taklamakan.