The Singapore Baha'i Studies Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia. A bibliography of historical and modern texts with introduction and partial annotation, and some echoes in Western countries. [This annotated bibliography of 220 items suggests the range and major themes of how Buddhism and people influenced by Buddhism have responded to disability in Asia through two millennia, with cultural background. Titles of the materials may be skimmed through in an hour, or the titles and annotations read in a day. The works listed might take half a year to find and read.] M. Miles (compiler and annotator) West Midlands, UK. November 2013 Available at: http://www.independentliving.org/miles2014a and http://cirrie.buffalo.edu/bibliography/buddhism/index.php Some terms used in this bibliography Buddhist terms and people. Buddhism, Bouddhisme, Buddhismus, suffering, compassion, caring response, loving kindness, dharma, dukkha, evil, heaven, hell, ignorance, impermanence, kamma, karma, karuna, metta, noble truths, eightfold path, rebirth, reincarnation, soul, spirit, spirituality, transcendent, self, attachment, clinging, delusion, grasping, buddha, bodhisatta, nirvana; bhikkhu, bhikksu, bhikkhuni, samgha, sangha, monastery, refuge, sutra, sutta, bonze, friar, biwa hoshi, priest, monk, nun, alms, begging; healing, therapy, mindfulness, meditation, Gautama, Gotama, Maitreya, Shakyamuni, Siddhartha, Tathagata, Amida, Amita, Amitabha, Atisha, Avalokiteshvara, Guanyin, Kannon, Kuan-yin, Kukai, Samantabhadra, Santideva, Asoka, Bhaddiya, Khujjuttara, -

The University of Chicago Practices of Scriptural Economy: Compiling and Copying a Seventh-Century Chinese Buddhist Anthology A

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRACTICES OF SCRIPTURAL ECONOMY: COMPILING AND COPYING A SEVENTH-CENTURY CHINESE BUDDHIST ANTHOLOGY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVINITY SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY ALEXANDER ONG HSU CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2018 © Copyright by Alexander Ong Hsu, 2018. All rights reserved. Dissertation Abstract: Practices of Scriptural Economy: Compiling and Copying a Seventh-Century Chinese Buddhist Anthology By Alexander Ong Hsu This dissertation reads a seventh-century Chinese Buddhist anthology to examine how medieval Chinese Buddhists practiced reducing and reorganizing their voluminous scriptural tra- dition into more useful formats. The anthology, A Grove of Pearls from the Garden of Dharma (Fayuan zhulin ), was compiled by a scholar-monk named Daoshi (?–683) from hundreds of Buddhist scriptures and other religious writings, listing thousands of quotations un- der a system of one-hundred category-chapters. This dissertation shows how A Grove of Pearls was designed by and for scriptural economy: it facilitated and was facilitated by traditions of categorizing, excerpting, and collecting units of scripture. Anthologies like A Grove of Pearls selectively copied the forms and contents of earlier Buddhist anthologies, catalogs, and other compilations; and, in turn, later Buddhists would selectively copy from it in order to spread the Buddhist dharma. I read anthologies not merely to describe their contents but to show what their compilers and copyists thought they were doing when they made and used them. A Grove of Pearls from the Garden of Dharma has often been read as an example of a Buddhist leishu , or “Chinese encyclopedia.” But the work’s precursors from the sixth cen- tury do not all fit neatly into this genre because they do not all use lei or categories consist- ently, nor do they all have encyclopedic breadth like A Grove of Pearls. -

The Daoist Tradition Also Available from Bloomsbury

The Daoist Tradition Also available from Bloomsbury Chinese Religion, Xinzhong Yao and Yanxia Zhao Confucius: A Guide for the Perplexed, Yong Huang The Daoist Tradition An Introduction LOUIS KOMJATHY Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 175 Fifth Avenue London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10010 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com First published 2013 © Louis Komjathy, 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Louis Komjathy has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury Academic or the author. Permissions Cover: Kate Townsend Ch. 10: Chart 10: Livia Kohn Ch. 11: Chart 11: Harold Roth Ch. 13: Fig. 20: Michael Saso Ch. 15: Fig. 22: Wu’s Healing Art Ch. 16: Fig. 25: British Taoist Association British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: 9781472508942 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Komjathy, Louis, 1971- The Daoist tradition : an introduction / Louis Komjathy. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4411-1669-7 (hardback) -- ISBN 978-1-4411-6873-3 (pbk.) -- ISBN 978-1-4411-9645-3 (epub) 1. -

A Abbasid Caliphate, 239 Relations Between Tang Dynasty China And

INDEX A anti-communist forces, 2 Abbasid Caliphate, 239 Antony, Robert, 200 relations between Tang Dynasty “Apollonian” culture, 355 China and, 240 archaeological research in Southeast Yang Liangyao’s embassy to, Asia, 43, 44, 70 242–43, 261 aromatic resins, 233 Zhenyuan era (785–805), 242, aromatic timbers, 230 256 Arrayed Tales aboriginal settlements, 175–76 (The Arrayed Tales of Collected Abramson, Marc, 81 Oddities from South of the Abu Luoba ( · ), 239 Passes Lĩnh Nam chích quái liệt aconite, 284 truyện), 161–62 Agai ( ), Princess, 269, 286 becoming traditions, 183–88 Age of Exploration, 360–61 categorizing stories, 163 agricultural migrations, 325 fox essence in, 173–74 Amarapura Guanyin Temple, 314n58 and history, 165–70 An Dương Vương (also importance of, 164–65 known as Thục Phán ), 50, othering savages, 170–79 165, 167 promotion of, 164–65 Angkor, 61, 62 savage tales, 179–83 Cham naval attack on, 153 stories in, 162–63 Angkor Wat, 151 versions of, 170 carvings in, 153 writing style, 164 Anglo-Burmese War, 294 Atwill, David, 327 Annan tuzhi [Treatise and Âu Lạc Maps of Annan], 205 kingdom, 49–51 anti-colonial movements, 2 polity, 50 371 15 ImperialChinaIndexIT.indd 371 3/7/15 11:53 am 372 Index B Biography of Hua Guan Suo (Hua Bạch Đằng River, 204 Guan Suo zhuan ), 317 Bà Lộ Savages (Bà Lộ man ), black clothing, 95 177–79 Blakeley, Barry B., 347 Ba Min tongzhi , 118, bLo sbyong glegs bam (The Book of 121–22 Mind Training), 283 baneful spirits, in medieval China, Blumea balsamifera, 216, 220 143 boat competitions, 144 Banteay Chhmar carvings, 151, 153 in southern Chinese local Baoqing siming zhi , traditions, 149 224–25, 231 boat racing, 155, 156. -

Dharaıi and SPELLS in MEDIEVAL SINITIC BUDDHISM It Has Become Common for Scholars to Interpret the Ubiquitous Presence of Dhara

DHARAıI AND SPELLS IN MEDIEVAL SINITIC BUDDHISM RICHARD D. MCBRIDE, II It has become common for scholars to interpret the ubiquitous presence of dhara∞i (tuoluoni ) and spells (zhou ) in medieval Sinitic Bud- dhism1 as evidence of proto-Tantrism in China2. For this reason, infor- mation associated with monk-theurgists and thaumaturges has been organ- ized in a teleological manner that presupposes the characteristics of a mature Tantric system and projects them backward over time onto an earlier period. Recently, however, scholars such as Robert H. Sharf have begun to point out the limitations of this approach to understanding the nature of Chinese Buddhism and religion3. This essay will address two inter-related questions: (1) How did eminent monks in medieval China conceptualize dhara∞i and spells? And (2) did they conceive of them as belonging exclusively to some defined tradition (proto-Tantric, Tantric, or something else)? In this essay I will present a more nuanced view of the mainstream Sinitic Buddhist understanding of dhara∞i and spells by providing back- ground on the role of spell techniques and spell masters in Buddhism and medieval Chinese religion and by focusing on the way three select The author of this article wishes to express gratitude to Gregory Schopen, Robert Buswell, George Keyworth, James Benn, Chen Jinhua, and the anonymous reviewer for their comments and suggestions on how to improve the article. 1 In this essay I deploy word “dhara∞i” following traditional Buddhist convention in both the singular and plural senses. I also use the word “medieval” rather loosely to refer to the period extending from the Northern and Southern Dynasties period through the end of the Tang, roughly 317-907 C.E. -

International Yearbook of Aesthetics Volume 18 | 2014 IAA Y Earbook

International Yearbook of Aesthetics Volume 18 | 2014 IAA Yearbook edited by Krystyna Wilkoszewska The 18th volume of the International Yearbook of Aesthet- ics comprises a selection of papers presented at the 19th International Congress of Aesthetics, which took place edited by Krystyna Wilkoszewska in Cracow in 2013. The Congress entitled “Aesthetics in Action” was in- tended to cover an extended research area of aesthet- ics going beyond the fine arts towards various forms of human practice. In this way it bore witness to the transformation that aesthetics has been undergoing for a few decades at the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries. edited by Krystyna Wilkoszewska International Yearbook of Aesthetics 2014 Volume 18 | 2014 ISBN 978-83-65148-21-6 International Association for Aesthetics International Association for Aesthetics Association Internationale d'Esthetique Wydawnictwo LIBRON | www.libron.pl 9 788365148216 edited by Krystyna Wilkoszewska edited by Krystyna Wilkoszewska Proceedings of the 19th International Congress of Aesthetics, Cracow 2013 International Yearbook of Aesthetics Volume 18 | 2014 International Association for Aesthetics Association Internationale d'Esthetique Cover design: Joanna Krzempek Layout: LIBRON Proofreading: Tim Hardy ISBN 978-83-65148-21-6 © Krystyna Wilkoszewska and Authors Publication financed by Institute of Philosophy of the Jagiellonian University Every efort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustrations reproduced in this book. Table of contents Krystyna Wilkoszewska -

A STUDY of the NAMES of MONUMENTS in ANGKOR (Cambodia)

A STUDY OF THE NAMES OF MONUMENTS IN ANGKOR (Cambodia) NHIM Sotheavin Sophia Asia Center for Research and Human Development, Sophia University Introduction This article aims at clarifying the concept of Khmer culture by specifically explaining the meanings of the names of the monuments in Angkor, names that have existed within the Khmer cultural community.1 Many works on Angkor history have been researched in different fields, such as the evolution of arts and architecture, through a systematic analysis of monuments and archaeological excavation analysis, and the most crucial are based on Cambodian epigraphy. My work however is meant to shed light on Angkor cultural history by studying the names of the monuments, and I intend to do so by searching for the original names that are found in ancient and middle period inscriptions, as well as those appearing in the oral tradition. This study also seeks to undertake a thorough verification of the condition and shape of the monuments, as well as the mode of affixation of names for them by the local inhabitants. I also wish to focus on certain crucial errors, as well as the insufficiency of earlier studies on the subject. To begin with, the books written in foreign languages often have mistakes in the vocabulary involved in the etymology of Khmer temples. Some researchers are not very familiar with the Khmer language, and besides, they might not have visited the site very often, or possibly also they did not pay too much attention to the oral tradition related to these ruins, a tradition that might be known to the village elders. -

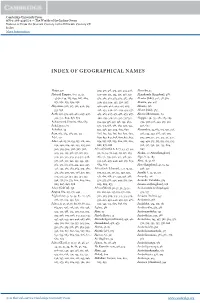

Index of Geographical Names

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42465-3 — The Worlds of the Indian Ocean Volume 2: From the Seventh Century to the Fifteenth Century CE Index More Information INDEX OF GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES Abaya, 571 309, 317, 318, 319, 320, 323, 328, Akumbu, 54 Abbasid Empire, 6–7, 12, 17, 329–370, 371, 374, 375, 376, 377, Alamkonda (kingdom), 488 45–70, 149, 185, 639, 667, 669, 379, 380, 382, 383, 384, 385, 389, Alaotra (lake), 401, 411, 582 671, 672, 673, 674, 676 390, 393, 394, 395, 396, 397, Alasora, 414, 427 Abyssinia, 306, 317, 322, 490, 519, 400, 401, 402, 409, 415, 425, Albania, 516 533, 656 426, 434, 440, 441, 449, 454, 457, Albert (lake), 365 Aceh, 198, 374, 425, 460, 497, 498, 463, 465, 467, 471, 478, 479, 487, Alborz Mountains, 69 503, 574, 609, 678, 679 490, 493, 519, 521, 534, 535–552, Aleppo, 149, 175, 281, 285, 293, Achaemenid Empire, 660, 665 554, 555, 556, 557, 558, 559, 569, 294, 307, 326, 443, 519, 522, Achalapura, 80 570, 575, 586, 588, 589, 590, 591, 528, 607 Achsiket, 49 592, 596, 597, 599, 603, 607, Alexandria, 53, 162, 175, 197, 208, Acre, 163, 284, 285, 311, 312 608, 611, 612, 615, 617, 620, 629, 216, 234, 247, 286, 298, 301, Adal, 451 630, 637, 647, 648, 649, 652, 653, 307, 309, 311, 312, 313, 315, 322, Aden, 46, 65, 70, 133, 157, 216, 220, 654, 657, 658, 659, 660, 661, 662, 443, 450, 515, 517, 519, 523, 525, 230, 240, 284, 291, 293, 295, 301, 668, 678, 688 526, 527, 530, 532, 533, 604, 302, 303, 304, 306, 307, 308, Africa (North), 6, 8, 17, 43, 47, 49, 607 309, 313, 315, 316, 317, 318, 319, 50, 52, 54, 70, 149, 151, 158, -

{PDF EPUB} Xunzi Basic Writings by Xun Kuang Xunzi 荀子

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Xunzi Basic Writings by Xun Kuang Xunzi 荀子. The book Xunzi 荀子 "Master Xun", also called Sunqingzi 孫卿子 or Xunqingzi 荀卿子, is a philosophical book of the late Warring States period 戰國 (5th cent-221 BCE). It belongs to the Confucian treatises but is not rated as a Confucian Classic because it contains numerous propositions that were for a long time classified as unorthodox. Xun Kuang. The author of the book Xunzi was Xun Kuang 荀況 (trad. 313-238 BCE) or Xun Qing 荀卿 (sometimes also called Sun Qing 孫卿), called Xunzi "Master Xun", a scholar from the regional state of Zhao 趙 who dwelled at the court of the kings of Qi 齊 where he was an eminent scholar at the Jixia state academy 稷下. When the state of Qi was conquered by the armies of Yan 燕, the scholars at the Academy were scattered into the four winds, and Xunzi went to the southern state of Chu 楚 to become a follower of Lord Chunshen 春申君. In 279 he returned to Qi, where he was at that time the most prominent teacher. After the death of King Xiang 齊襄王 (r. 283-265), he left Qi and served King Zhaoxiang of Qin 秦昭襄王 (r. 306-251). He admired the results of the administrative reform in that state, but also stressed that Qin was lacking the advice of experts in ritual matters, and therefore only used a combination of codified bureaucracy with an expansive militarism which would in the eyes of Xunzi not good in the long run. -

Rūta Stanevičiūtė Nick Zangwill Rima Povilionienė Editors Between Music

Numanities - Arts and Humanities in Progress 7 Rūta Stanevičiūtė Nick Zangwill Rima Povilionienė Editors Of Essence and Context Between Music and Philosophy Numanities - Arts and Humanities in Progress Volume 7 Series Editor Dario Martinelli, Faculty of Creative Industries, Vilnius Gediminas Technical University, Vilnius, Lithuania [email protected] The series originates from the need to create a more proactive platform in the form of monographs and edited volumes in thematic collections, to discuss the current crisis of the humanities and its possible solutions, in a spirit that should be both critical and self-critical. “Numanities” (New Humanities) aim to unify the various approaches and potentials of the humanities in the context, dynamics and problems of current societies, and in the attempt to overcome the crisis. The series is intended to target an academic audience interested in the following areas: – Traditional fields of humanities whose research paths are focused on issues of current concern; – New fields of humanities emerged to meet the demands of societal changes; – Multi/Inter/Cross/Transdisciplinary dialogues between humanities and social and/or natural sciences; – Humanities “in disguise”, that is, those fields (currently belonging to other spheres), that remain rooted in a humanistic vision of the world; – Forms of investigations and reflections, in which the humanities monitor and critically assess their scientific status and social condition; – Forms of research animated by creative and innovative humanities-based -

The Journal of Taoist Philosophy and Practice

The Journal of Taoist Philosophy and Practice Summer 2015 $5.95 U.S. $6.95 Canada The Five Fold Essence of Tea The Story of the Tao Te Ching The Functions of Essence, Breath and Spirit The Empty Vessel Interview: with Master Yang Hai and more! The Empty Vessel A Book to Guide the Way DAOIST NEI GONG The Philosophical Art of Change Damo Mitchell For the first time in the English language, this book describes the philosophy and practice of Nei Gong. The author explains the philosophy which underpins this practice, and the methodology of Sung breathing, an advanced meditative practice, is described. The book also contains a set of Qigong exercises, accompanied by instructional illustrations. $24.95 978-1-84819-065-8 PAPERBACK THE FOUR THE FOUR DRAGONS DIGNITIES Clearing the Meridians and The Spiritual Practice of Awakening the Spine in Walking, Standing, Sitting, and Nei Gong Lying Down Damo Mitchell Cain Carroll $29.95 $24.95 978-1-84819-226-3 978-1-84819-216-4 PAPERBACK PAPERBACK CHA DAO DAOIST The Way of Tea, MEDITATION Tea as a Way of Life The Purification of the Heart Solala Towler Method of Meditation and Discourse on Sitting and $17.95 Forgetting (Zuò Wàng Lùn) by 978-1-84819-032-0 Si Ma Cheng Zhen PAPERBACK Translated by Wu Jyh Cherng $49.95 978-1-84819-211-9 PAPERBACK WWW.SINGINGDRAGON.COM A Book to Guide the Way Step Into the Tao DAOIST NEI GONG with Dr. and Master Zhi Gang Sha New York Times Best Selling Author, Doctor of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Western Medicine The Philosophical Art of Change Damo Mitchell Tao is The Way of all life. -

Chinese Letters and Intellectual Life in Medieval Japan: the Poetry and Political Philosophy of Chūgan Engetsu

Chinese Letters and Intellectual Life in Medieval Japan: The Poetry and Political Philosophy of Chūgan Engetsu By Brendan Arkell Morley A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese Language in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor H. Mack Horton Professor Alan Tansman Professor Paula Varsano Professor Mary Elizabeth Berry Summer 2019 1 Abstract Chinese Letters and Intellectual Life in Medieval Japan: The Poetry and Political Philosophy of Chūgan Engetsu by Brendan Arkell Morley Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese University of California, Berkeley Professor H. Mack Horton, Chair This dissertation explores the writings of the fourteenth-century poet and intellectual Chūgan Engetsu 中巌円月, a leading figure in the literary movement known to history as Gozan (“Five Mountains”) literature. In terms of modern disciplinary divisions, Gozan literature straddles the interstices of several distinct areas of study, including classical Chinese poetry and poetics, Chinese philosophy and intellectual history, Buddhology, and the broader tradition of “Sinitic” poetry and prose (kanshibun) in Japan. Among the central contentions of this dissertation are the following: (1) that Chūgan was the most original Confucian thinker in pre-Tokugawa Japanese history, the significance of his contributions matched only by those of early-modern figures such as Ogyū Sorai, and (2) that kanshi and kanbun were creative media, not merely displays of erudition or scholastic mimicry. Chūgan’s expository writing demonstrates that the enormous multiplicity of terms and concepts animating the Chinese philosophical tradition were very much alive to premodern Japanese intellectuals, and that they were subject to thoughtful reinterpretation and application to specifically Japanese sociohistorical phenomena.