Download Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 to 15 May, 2008

PPPaaarrrllliiiaaammmeeennntttaaarrryyy DDDooocccuuummmeeennntttaaatttiiiooonnn VVVooolll XXXXXXXXXIIIVVV (((111 tttooo 111555 MMMaaayyy,,, 222000000888))) NNNooo... 999 AGRICULTURE -(INDIA) 1 KADAMBOT SIDDIQUE Challenge and opportunity in agriculture. HINDU, 2008(2.5.2008) ** Agriculture-(India). -AGRICULTURAL COMMODITIES-COTTON 2 DESAI, Sachiketa Taking the organic route. BUSINESS INDIA, No.782, 2008(9.3.2008): P.110-111 Examines India's emergence as world's top producer of Organic cotton. ** Agriculture-Agricultural commodities-Cotton; Organic farming -AGRICULTURAL COMMODITIES-SUGARCANE 3 ANTONY, M.J. Bitter battles in the sugar fields. BUSINESS STANDARD, 2008(14.5.2008) Focuses on lack of rationalisation of sugarcane prices and coordinated policy. ** Agriculture-Agricultural Commodities-Sugarcane. -AGRICULTURAL COMMODITIES-TEA 4 SATYA SUNDARAM, I Tea: Facing rough weather. FACTS FOR YOU, V.28(No.5), 2008(February): P.7-9 ** Agriculture-Agricultural commodities-Tea. -AGRICULTURAL COMMODITIES-VEGETABLES 5 RAHUL JAYARAM Brinjal battles. TELEGRAPH, 2008(14.5.2008) Focuses on controversies related with genetically modified brinjals. ** Agriculture-Agricultural Commodities-Vegetables. ** - Keywords 1 -AGRICULTURAL CREDIT 6 GOSWAMI, Anupam Credit for a waiver. BUSINESS INDIA, No.784, 2008(6.4.2008): P.42-44 Analyses the consequences of farm loan waiver scheme announced in the current budget. ** Agriculture-Agricultural Credit. 7 JOSHI, Rakesh Notes for votes. BUSINESS INDIA, No.783, 2008(23.3.2008): P.98-104 Highlights the loan waiver package offered to farmers in the present budget. ** Agriculture-Agricultural Credit. -AGRICULTURAL POLICY-(INDIA) 8 Prospects of agriculture. ASSAM TRIBUNE, 2008(7.5.2008) ** Agriculture-Agricultural Policy-(India). 9 SHARMA, Manish Optimise the food-energy mix. FINANCIAL EXPRESS, 2008(7.5.2008) Emphasises the need for comprehensive agriculture sector reforms. -

Questions & Solutions

ENGLISH NDA-2012 EXAMINATION CAREER POINT QUESTIONS & SOLUTIONS PART – A Direction (For the next 08 items which follow) : Read the following 02 passages and answer the questions that following each passage : Passage – 1 There was a farewell ceremony on here day at school, to which my parents and I were invited. It was a touching ceremony in a solemn kind of way. The City Corporation sent a representative and so did the two main political parties. There were many speeches and my grandmother was garlanded by a girl from every class. Then the haed-girl, a particular favourite of hers, unveiled the farewell present the girls had bought for her by subscription. It was a large marble model of the Taj Mahal; it had a bulb inside and could be lit up like a table lamp. My grandmother made a speech too, but she couldn't finish it properly, for she began to cry before she got to the end of it and to stop to wipe away her tears. I turned away when she began dabbing at her eyes with a huge green handkerchief and discovered, to my surprise, that many of the girls sitting around me were wiping their green hankerchief and discovered, to my surprise. that many of the girls sitting around me were wiping their eyes too. I was very jealous. I remember. I had always taken it for granted that it was my own special right to love her ; I did know how to cope with the discovery that my right had been infringed by a whole school. -

I Semester II Semester

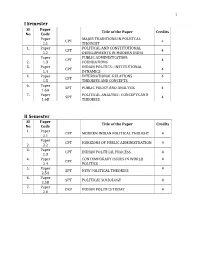

1 I Semester Sl Paper Title of the Paper Credits No Code Paper MAJOR TRADITIONS IN POLIITCAL CPT 4 1.1 THOUGHT 1. Paper POLITICAL AND CONSTITUTIONAL CPT 4 1.2 DEVELOPMENTS IN MODERN INDIA Paper PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION: CPT 4 2. 1.3 FOUNDATIONS 3. Paper INDIAN POLITICS : INSTITUTIONAL CPT 4 1.4 DYNAMICS 4. Paper INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS : 4 CPT 1.5 THEORIES AND CONCEPTS 6. Paper SPT PUBLIC POLICY AND ANALYSIS 4 1.6A 7. Paper POLITICAL ANALYSIS : CONCEPTS AND SPT 4 1.6B THEORIES II Semester Sl Paper Title of the Paper Credits No Code 1. Paper CPT MODERN INDIAN POLITICAL THOUGHT 4 2.1 Paper CPT HORIZONS OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION 4 2. 2.2 3. Paper CPT INDIAN POLITICAL PROCESS 4 2.3 4. Paper CONTEMPORARY ISSUES IN WORLD 4 CPT 2.4 POLITICS 5. Paper 4 SPT NEW POLITICAL THEORIES 2.5A 6. Paper SPT POLITICAL SOCIOLOGY 4 2.5B 7. Paper OEP INDIAN POLITICS TODAY 4 2.6 III Semester Sl Paper Title of the Paper Credits No Code 1. Paper DEBATES IN CONTEMPORARY POLITICAL 4 CPT 3.1 THEORY Paper CPT PUBLIC GOVERNANCE 4 2. 3.2 3. Paper DIMENSIONS OF DEVELOPMENT IN CPT 4 3.3 KARNATAKA 4. Paper 4 CPT RESEARCH METHODS IN SOCIAL SCIENCE 3.4 5. Paper 4 SPT RURAL GOVERNANCE IN INDIA 3.5A 6. Paper SPT GLOBAL CHALLENGES 4 3.5B 7. Paper OEP HUMAN RIGHTS : ISSUES AND CHALLENGES 4 3.6 IV Semester Sl Paper Title of the Paper Credits No Code 1. Paper MODERN WESTERN POLITICAL CPT 4 4.1 THOUGHT Paper GOVERNMENT AND POLITICS IN CPT 4 2. -

Government of Karnataka Department of Collegiate Education Sri Mahadeshwara Government First Grade College Kollegal-571440 Department of Economics

Government of Karnataka Department of Collegiate Education Sri Mahadeshwara Government First Grade College Kollegal-571440 Department of Economics LESSON PLAN FOR THE ACADEMIC YEAR: 2015-16 Programme: Arts Course/Paper Name: Principles of Macro Economics Semester: II semester Class: B.A Sl. Unit Unit to be covered as Date Unit related events / No prescribed by the components for effective university From To curriculum delivery 01. I An Overview of 11/01/2016 10/02/2016 Unit Test, Unit wise Macroeconomics : Assignment, Seminar by Macroeconomics: Meaning, Students, Group Types and Scope - discussion. Importance and Limitations - Basic Concepts of Macroeconomics, Stocks, Flow and Equilibrium - National Income: Meaning and Importance - Concepts - GDP, GNP, NDP, NNP, NI, PI, DPI and Per capita Income - Circular Flow of Income 02. II Classical Theory of 11/02/2016 02/03/2016 Unit Test, Unit wise Employment: Basic Assignment, Seminar by Assumptions of Classical Students, Group Theory - Classical Theory discussion. of Employment - Say’s Law of Market - Wage - Price Flexibility (Pigou’s Version) - Saving and Investment Equality - Evaluation of the Classical Theory of Employment 03. III Keynesian Theory: 03/03/2016 01/04/2016 Unit Test, Unit wise Concepts of Effective Assignment, Seminar by Demand and its Students, Group Determinants. Equilibrium discussion. Level of Income and Employment. Consumption Function: Psychological Law of Consumption, Factors Affecting Consumption Function. Investment Function: Factors Affecting Investment Function. Multipiler - Evaluation of the Keynesian Theory of Employment. 04. IV Inflation, Deflation and 02/04/2016 29/04/2016 Unit Test, Unit wise Business Cycle: Inflation: Assignment, Seminar by Meaning and Types - Students, Group Causes and Effects of discussion. -

Change in Rural Karnataka Over the Last Generation

Draft: Not to be quoted CHANGE IN KARNATAKA OVER THE LAST GENERATION: VILLAGES AND THE WIDER CONTEXT James Manor Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex 1 I. INTRODUCTION This paper examines changes that have (and have not) occurred – at the village level in Karnataka where most or the state’s residents live, and at higher levels when they impinge upon villages – since 1972. Throughout this discussion, we often encounter an oddity. Substantial changes have occurred on many (though certainly not all) fronts, but most of them have not resulted from conscious decisions by political leaders to induce dramatic change. With a small number of exceptions, political leaders have been distinctly reluctant to attempt marked changes of any description. They have not remained inert - nearly all governments have introduced changes. But almost all have proceeded quite cautiously, concentrating almost exclusively on incremental change. Four exceptions to this tendency are worth briefly noting here at the outset -- because they were important, but also to indicate how few of them there were. a) This story begins at a point – in 1972 – when Chief Minister Devaraj Urs (with the help of Karnataka’s voters) achieved a substantial, startling change. He broke the dominance that Lingayats and Vokkaligas had exercised over state-level politics since Independence. b) In 1983, the state’s party system changed when the Congress Party lost a state election for the first time. Since then, the alternation of parties at state elections has (with one notable exception) been then norm. c) After 1985, a Janata government generously empowered and funded panchayati raj institutions. -

Shree Khasgatesh College of Arts and Commerce, Talikoti-586 214

V.V.Sangha’s Shree Khasgatesh College of Arts and Commerce, Talikoti-586 214 Veerashaiva Vidyavardhak Sangha‘s SHREE KHASGATESH COLLEGE OF ARTS AND COMMERCE, TALIKOTI – 586214 DIST. VIJAYAPUR KARNATAKA (Affiliated to Rani Channamma University, Belagavi) Website:www.skctalikoti.com Email:[email protected] Phone No./Fax : 08356-266310 Cell : 9740220318 Self Study Report Submitted to National Assessment and Accreditation Council For 3rd Cycle of Accreditation January, 2016 SSR for Third Cycle of Accreditation…. V.V.Sangha’s Shree Khasgatesh College of Arts and Commerce, Talikoti-586 214 Shri. Khasgata Shivayogigalu SSR for Third Cycle of Accreditation…. V.V.Sangha’s Shree Khasgatesh College of Arts and Commerce, Talikoti-586 214 Shri. Ma. Ni. Pra. Virakta Mahaswamigalu SSR for Third Cycle of Accreditation…. V.V.Sangha’s Shree Khasgatesh College of Arts and Commerce, Talikoti-586 214 CONTENTS Sl. No. Particulars Page No. 1 Covering letter 01 2 Preface and Executive Summary : The SWOC Analysis 02-13 3 Profile of the Institution : Institutional data 14-22 4 Criteria-Wise Analytical Report Criterion – I – Curricular Aspects 23-37 Criterion – II – Teaching-Learning and Evaluation 38-75 Criterion – III – Research, Consultancy and Extension 76-101 Criterion – IV – Infrastructure and Learning Resources 102-117 Criterion – V – Student Support and Progression 118-142 Criterion – VI -- Governance, Leadership and 143-166 Management Criterion – VII - Innovations and Best Practices 167-176 5 Evaluative Report of the Departments 177-234 6 Post Accreditation Initiatives 235-236 7 Compliance Report 237 8 Declaration by the Head of the Institution 238 9 Enclosures 239-287 SSR for Third Cycle of Accreditation…. -

Suppl. Syn. E Dt. 26.11.07.Pdf

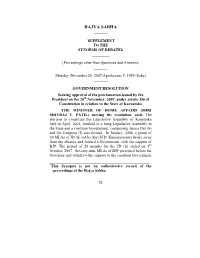

RAJYA SABHA _______ *SUPPLEMENT TO THE SYNOPSIS OF DEBATES _________ (Proceedings other than Questions and Answers) _______ Monday, November 26, 2007/Agrahayana 5, 1929 (Saka) _______ GOVERNMENT RESOLUTION Seeking approval of the proclamation issued by the President on the 20th November, 2007, under article 356 of Constitution in relation to the State of Karnataka THE MINISTER OF HOME AFFAIRS (SHRI SHIVRAJ V. PATIL) moving the resolution, said: The election to constitute the Legislative Assembly of Karnataka held in April, 2004, resulted in a hung Legislative Assembly in the State and a coalition Government, comprising Janata Dal (S) and the Congress (I) was formed. In January, 2006, a group of 39 MLAs of JD (S) led by Shri H.D. Kumaraswamy broke away from the alliance and formed a Government, with the support of BJP. The period of 20 months for the JD (S) ended on 3rd October, 2007. Seventy-nine MLAs of BJP presented before the Governor and withdrew the support to the coalition Government ___________________________________________________ *This Synopsis is not an authoritative record of the proceedings of the Rajya Sabha. 92 on 6th October, 2007. Thereafter, the Chief Minister met the Governor and submitted his resignation on 8th October, 2007. The Governor, recommended invoking the President's rule in the State of Karnataka and the President's rule was proclaimed on 9th October, 2007 in the State of Karnataka under article 356 (1) of the Constitution keeping the Legislative Assembly under suspended animation. On 29th October, 2007, the JD(S)-BJP combine submitted 129 letters of individual support to the Governor -- 79 BJP, 41 JD(S), 3 JD(U) and 6 Independents -- and also signed in the register at Raj Bhawan. -

Modi's Trump Card

Established 1946 1 Pages 16 Price : Rupees Five Vol. 72 No. 24 Modi’s Trump Card July 2, 2017 Kuldip Nayar A Policy to Eliminate Every statement or a visit by a exactly what you have, a true Toiletless People foreign dignitary has to be related friend…I am thrilled to salute you, Sandeep Pandey to our attitude on Pakistan. Even Prime Minister Modi, and the if there is no mention of Islamabad, Indian people for all that you are we stretch the observation to the accomplishing together. Your point where it is meant to be so. accomplishments have been vast,” PM Modi in USA American Presidents have so far said Trump. The President also D. K. Giri been hedging an open criticism of described Prime Minister Modi Pakistan because the US has been and himself as “world leaders in supplying arms to Islamabad. But social media” and that it has In the Name of Public for the first time, America has enabled them to directly hear from Interest dropped ifs and buts to pull up their citizens.” J. L. Jawahar Pakistan for abetting terrorism and giving shelter to the militants. In the past, India had friendly presidents in John F. Kennedy, Bill President Donald Trump in a joint Clinton and Barrack Obama. But Fast Against Lynching statement with Prime Minister they did very little to help New Delhi Dr. Prem Singh Narendra Modi, following their first in its strategic and development meeting at the White House, made requirements. They were obsessed terrorism the cornerstone of mutual with the thought that they should cooperation between the two not in any way rub Pakistan on the countries. -

Political Science BA Optional Syllabus

Political Science BA Optional Syllabus Semester I Political Theory 80 Marks 5 hrs per week Semester II Political Thought 80 Marks 5 hrs per week a) Western Political Thinkers b) Indian Political Thinkers Semester III Indian Government & Politics 80 Marks 5 hrs per week Semester IV Karnataka Government & Politics 80 Marks 5 hrs per week Semester V Compulsory paper Public Administration 80 Marks 5 hrs per week Paper II Elective Paper-1 80 Marks 5 hrs per week Modern Governments (United Kingdom & Switzerland) or Indian Administration 80 Marks 5 hrs per week Semester VI Compulsory paper International Relations 80 Marks 5 hrs per week Paper II Elective Papers Political Process & Institutions in India 80 Marks 5 hrs per week or Indian Foreign Policy 80 Marks 5 hrs per week Political Science Optional B.A. Semester – I Political Theory 80 Marks 5 hrs per week Chapter- 1:Political Theory 1) Meaning Nature, Scope and Importance of Political Theory 2) Approaches to Political Theory :- Normative, Historical & Empirical Chapter-2:State Meaning and Elements Theories of the Origin of the State- Divine origin theory, , Social contract theory, State, Historical Theory, Nation and Civil Society. Chapter-3: Sovereignty Meaning and perspectives of Sovereignty, Austins Theory, Pluralist Theory, Sovereignty in the age of Globalisation. Chapter-4: Basic Concepts Liberty : Meaning and kinds of Liberty Equality :,Meaning Importance and kinds of equality Rights : Meaning ,importance, kinds of Rights Natural Theory of Rights Law : Meaning Importance and kinds of Law Justice : Meaning, and Kinds- John Rawls theory of Justice Chapter-5 Political Ideologies Socialism : Meaning and Importance Democracy : Meaning,forms and Kinds of Democracy Challenges to Democracy – Inequality, Communalism Corruption, Terrorism, End of Ideology Debate Books Reference 1. -

The Making of the 2019 Verdict

EEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEE DELHI THE HINDU 10 EDITORIAL MONDAY, MAY 27, 2019 EEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEE The making of the 2019 verdict Voters want someone who will protect them from insecurities flowing from the new economy and globalisation Narendra Modi who had held pow dia, contract labour was cial esteem, the politics of frustra er for more than 12 continuous introduced in the organised work tion and social envy have been years in Gujarat before he became ing class. This generated tremen harnessed to a project of xeno Facing the debacle Prime Minister. Three, authoritar dous insecurity. Public enterprises phobic nationalism. In this mood Congress’s stocktaking must be deeper than ian populist leaders prefer to were privatised and workers were of nationalism anyone who is not speak directly to an inchoate and thrown onto the street. Here they -

![Rethinking State Politics in India Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:31 24 May 2016 Rethinking State Politics in India](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4370/rethinking-state-politics-in-india-downloaded-by-university-of-defence-at-01-31-24-may-2016-rethinking-state-politics-in-india-4024370.webp)

Rethinking State Politics in India Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:31 24 May 2016 Rethinking State Politics in India

Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:31 24 May 2016 Rethinking State Politics in India Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:31 24 May 2016 Rethinking State Politics in India Regions within Regions Editor Ashutosh Kumar Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:31 24 May 2016 LONDON NEW YORK NEW DELHI First published 2011 in India by Routledge 912–915 Tolstoy House, 15–17 Tolstoy Marg, Connaught Place, New Delhi 110 001 Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2011 Ashutosh Kumar Typeset by Star Compugraphics Private Limited D–156, Second Floor Sector 7, Noida 201 301 Printed and bound in India by Baba Barkha Nath Printers MIE-37, Bahadurgarh, Haryana 124507 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the publishers. Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:31 24 May 2016 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 978-0-415-59777-7 This book is printed on ECF environment-friendly paper manufactured from unconventional and other raw materials sourced from sustainable and identified sources. Contents List of Tables and Charts ix Preface and Acknowledgements xiii Introduction — Rethinking State Politics in India: Regions within Regions 1 Ashutosh Kumar Part I: United Colours of New States 1. -

The Case of Karnataka's Biotechnology Policy

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IDS OpenDocs IDS Working Paper 196 Making policy in the “new economy”: the case of biotechnology in Karnataka, India Ian Scoones July 2003 INSTITUTE OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES Brighton, Sussex BN1 9RE ENGLAND i © Institute of Development Studies, 2003 ISBN 1 85864 509 3 ii Summary This paper is a story of the making of a policy, one that included many different players, located across a variety of sites. By tracing the origins of the millennium biotechnology policy in Karnataka state, south India, examining the content of and participants in the debate that led up to it, and analysing the final result and some of its consequences, the paper attempts to understand what policy-making means in practice. Who are the policy-makers? What is a policy? What are the technical, political and bureaucratic inputs to policy-making? These questions are asked for a much hyped, hi-tech sector – biotechnology – seen by some as a key to future economic development, and central to the “new economy” of the post- reform era in India. The paper argues that a new style of politics is emerging in response to the changing contexts of the “new economy” era. This is particularly apparent in the hi-tech, science-driven, so-called knowledge economy sectors, where a particular form of science-industry expertise is deemed essential. The paper shows how the politics of policy-making is a long way from previous understandings of the policy process in India, based on the assumptions of a centralised planned economy where states danced to the centre’s tune and the private sector was not a major player.