Caste Associations in the Post-Mandal Era: Notes from Maharashtra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender Quotas and Caste in India

Competing Inequalities? Gender Quotas and Caste in India Alexander Lee* Varun Karekurve-Ramachandra† March 27, 2019 Short Title: Competing Inequalities Key Words: Gender Quotas, India, Women in Politics, Caste, Intersectionality *Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, University of Rochester. 333 Harkness Hall Rochester NY 14627. Email: [email protected] †PhD Student, Department of Political Science, University of Rochester. 333 Harkness Hall Rochester NY 14627. Email: [email protected]. The authors gratefully acknowledge Charles E Lanni fellowship that funded a part of this research. The authors also thank Prof. Rajeev Gowda, Ramprasad Alva and Avinash Gowda for help and encouragement during fieldwork in Delhi, the Takshashila Insti- tution and PRS Legislative Research for providing working space and amazing hospitality in Bengaluru and New Delhi respectively, and Harnidh Kaur for research assistance. Alessio Albarello, Sergio Ascensio, Emiel Awad, Tiffany Barnes, Salil Bijur, Saurabh Chandra, Praveen Chandrashekaran, Zuheir Desai, Ramanjit Duggal, Olga Gasparyan, Gretchen Helmke, Aravind Gayam, Aparna Goel, Nidhi Gupta, Gleason Judd, Adam Kaplan, Pranay Kotasthane, Sanjay Kumar, M.R.Madhavan, Prachee Mishra, Meenakshi Narayanan, Sundeep Narwani, Jack Paine, Aman Panwar, Akhila Prakash, Vibhor Relhan, Maria Silfa, Pavan Srinath, Ramachan- dra Shingare, Aruna Urs and Yannis Vassiliadis provided constructive suggestions, help, and comments. Responsibility for any errors remains our own. 1 Competing Inequalities? Gender Quotas and Caste in India Abstract How do political gender quotas affect representation? We suggest that when gender attitudes are correlated with ethnicity, promoting female politicians may reduce the descriptive representation of traditionally disadvantaged ethnic groups. To assess this idea, we examine the consequences of the implementation of random electoral quotas for women on the representation of caste groups in Delhi. -

The History of Punjab Is Replete with Its Political Parties Entering Into Mergers, Post-Election Coalitions and Pre-Election Alliances

COALITION POLITICS IN PUNJAB* PRAMOD KUMAR The history of Punjab is replete with its political parties entering into mergers, post-election coalitions and pre-election alliances. Pre-election electoral alliances are a more recent phenomenon, occasional seat adjustments, notwithstanding. While the mergers have been with parties offering a competing support base (Congress and Akalis) the post-election coalition and pre-election alliance have been among parties drawing upon sectional interests. As such there have been two main groupings. One led by the Congress, partnered by the communists, and the other consisting of the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) and Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). The Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) has moulded itself to joining any grouping as per its needs. Fringe groups that sprout from time to time, position themselves vis-à-vis the main groups to play the spoiler’s role in the elections. These groups are formed around common minimum programmes which have been used mainly to defend the alliances rather than nurture the ideological basis. For instance, the BJP, in alliance with the Akali Dal, finds it difficult to make the Anti-Terrorist Act, POTA, a main election issue, since the Akalis had been at the receiving end of state repression in the early ‘90s. The Akalis, in alliance with the BJP, cannot revive their anti-Centre political plank. And the Congress finds it difficult to talk about economic liberalisation, as it has to take into account the sensitivities of its main ally, the CPI, which has campaigned against the WTO regime. The implications of this situation can be better understood by recalling the politics that has led to these alliances. -

Theoretical Debates About the Scheduled Caste Mlas Performance

© 2018 JETIR October 2018, Volume 5, Issue 10 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) THEORETICAL DEBATES ABOUT THE SCHEDULED CASTE MLAS PERFORMANCE Dr. Bal Kamble Principal, Rayat Shikshan Sanstha’s, Dada Patil Mahavidyalaya, Karjat, Dist.- Ahmednagar (M.S.) Abstract : For the study of Indian Political Process, study of state level politics is necessary. Through state level politics, national level politics can be studied in two ways. We get common issues which are useful for the comparison of state politics. Special features of the states are come to know through this study. In this relation, one kind of research has not been done yet about the performance of the SC MLAs elected from reserved seats. In this research paper effort is made to review the past studies related to this research. On the basic of number, MLAs has performed well in and outside the legislature. For examples, in Maharashtra Maratha leadership which have majority population performed well in and outside the legislature. IndexTerms – Caste, Customs, Untouchability, Power, Reservation, Auhtority, Urbanization, Dominant, Bahujan. Discussion of the scholars about the caste:- Caste is the social and economic factor which have co-relation with Indian politics. In fact it can be said, the study of Indian political process without the basis of caste politics, will be irrelevant. Caste politics study is made by thinker and experts, through socio-political and socio-economical approaches. In traditional caste system, society is divided into four layers on the basis of social status. Caste membership is decided by birth. Higher-lower social hierarchical structure, strict restriction on social interactions, inequality in social and religious qualification and rights, strict restrictions on occupation choice, strict rule caste internal marriage, are the pecular features of the Hindu traditional Caste system. -

1 to 15 May, 2008

PPPaaarrrllliiiaaammmeeennntttaaarrryyy DDDooocccuuummmeeennntttaaatttiiiooonnn VVVooolll XXXXXXXXXIIIVVV (((111 tttooo 111555 MMMaaayyy,,, 222000000888))) NNNooo... 999 AGRICULTURE -(INDIA) 1 KADAMBOT SIDDIQUE Challenge and opportunity in agriculture. HINDU, 2008(2.5.2008) ** Agriculture-(India). -AGRICULTURAL COMMODITIES-COTTON 2 DESAI, Sachiketa Taking the organic route. BUSINESS INDIA, No.782, 2008(9.3.2008): P.110-111 Examines India's emergence as world's top producer of Organic cotton. ** Agriculture-Agricultural commodities-Cotton; Organic farming -AGRICULTURAL COMMODITIES-SUGARCANE 3 ANTONY, M.J. Bitter battles in the sugar fields. BUSINESS STANDARD, 2008(14.5.2008) Focuses on lack of rationalisation of sugarcane prices and coordinated policy. ** Agriculture-Agricultural Commodities-Sugarcane. -AGRICULTURAL COMMODITIES-TEA 4 SATYA SUNDARAM, I Tea: Facing rough weather. FACTS FOR YOU, V.28(No.5), 2008(February): P.7-9 ** Agriculture-Agricultural commodities-Tea. -AGRICULTURAL COMMODITIES-VEGETABLES 5 RAHUL JAYARAM Brinjal battles. TELEGRAPH, 2008(14.5.2008) Focuses on controversies related with genetically modified brinjals. ** Agriculture-Agricultural Commodities-Vegetables. ** - Keywords 1 -AGRICULTURAL CREDIT 6 GOSWAMI, Anupam Credit for a waiver. BUSINESS INDIA, No.784, 2008(6.4.2008): P.42-44 Analyses the consequences of farm loan waiver scheme announced in the current budget. ** Agriculture-Agricultural Credit. 7 JOSHI, Rakesh Notes for votes. BUSINESS INDIA, No.783, 2008(23.3.2008): P.98-104 Highlights the loan waiver package offered to farmers in the present budget. ** Agriculture-Agricultural Credit. -AGRICULTURAL POLICY-(INDIA) 8 Prospects of agriculture. ASSAM TRIBUNE, 2008(7.5.2008) ** Agriculture-Agricultural Policy-(India). 9 SHARMA, Manish Optimise the food-energy mix. FINANCIAL EXPRESS, 2008(7.5.2008) Emphasises the need for comprehensive agriculture sector reforms. -

India's 2019 National Election and Implications for U.S. Interests

India’s 2019 National Election and Implications for U.S. Interests June 28, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45807 SUMMARY R45807 India’s 2019 National Election and Implications June 28, 2019 for U.S. Interests K. Alan Kronstadt India, a federal republic and the world’s most populous democracy, held elections to seat a new Specialist in South Asian lower house of parliament in April and May of 2019. Estimates suggest that more than two-thirds Affairs of the country’s nearly 900 million eligible voters participated. The 545-seat Lok Sabha (People’s House) is seated every five years, and the results saw a return to power of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who was chief minister of the west Indian state of Gujarat from 2001 to 2014. Modi’s party won decisively—it now holds 56% of Lok Sabha seats and Modi became the first Indian leader to win consecutive majorities since Indira Gandhi in 1971. The United States and India have been pursuing an expansive strategic partnership since 2005. The Trump Administration and many in the U.S. Congress welcomed Modi’s return to power for another five-year term. Successive U.S. Presidents have deemed India’s growing power and influence a boon to U.S. interests in Asia and globally, not least in the context of balancing against China’s increasing assertiveness. India is often called a preeminent actor in the Trump Administration’s strategy for a “free and open Indo-Pacific.” Yet there are potential stumbling blocks to continued development of the partnership. -

TYBA POLITICAL SCIENCE - PAPER VI DETERMINANTS of POLITICS of MAHARASHTRA SAMPLE Mcqs

TYBA POLITICAL SCIENCE - PAPER VI DETERMINANTS OF POLITICS OF MAHARASHTRA SAMPLE MCQs Q.1 The relationship between business class and politics existed A. Even Pre-1947 B. Only Post-1947 C. Only after 1960s D. Only after 1990s Q.2 Which business house had intimate relationship with Indian national Congress in the pre-independence days A. Adani B. Ambani C. Bajaj D. Pendharkar Q.3 The commercial capital of India A. Delhi B. Mumbai C. Bangalore D. Calcutta Q.4 The business class is regarded as A. Religious interest group. B. Social interest group. C. Cultural interest group. D. Institutional interest group. Q.5 The associations of business classes are called A. Congress of commerce B. Forum of commerce C. Platform of commerce D. Chambers of commerce Q.6 The Indian Merchants Chamber was established in A. 1887 B. 1900 C. 1905 D. 1907 Q.7 Which nationalist leader had his influence in working of chambers of commerce in the pre-independence days? A. Netaji Bose B. Dadabhai Naoroji C. Sardar Patel D. Lokmanya Tilak Q.8 Which act provided 4 seats to the Indian business community in the Central Legislature A. Act of 1905 B. Act of 1910 C. Act of 1919 D. Act of 1930 Q.9 Which State has the largest no. of co-operative institutes in India? A. Bihar B. Manipur C. Maharashtra D. Assam Q.9 Who was the first CM of Maharashtra ? A. Y.B. Chavan B. V.P. Naik C. Vasantdada Patil D. A.R. Antulay Q.10 The no. of co-operative institutions in Maharashtra in 1961 were A. -

Political Economy of a Dominant Caste

Draft Political Economy of a Dominant Caste Rajeshwari Deshpande and Suhas Palshikar* This paper is an attempt to investigate the multiple crises facing the Maratha community of Maharashtra. A dominant, intermediate peasantry caste that assumed control of the state’s political apparatus in the fifties, the Marathas ordinarily resided politically within the Congress fold and thus facilitated the continued domination of the Congress party within the state. However, Maratha politics has been in flux over the past two decades or so. At the formal level, this dominant community has somehow managed to retain power in the electoral arena (Palshikar- Birmal, 2003)—though it may be about to lose it. And yet, at the more intricate levels of political competition, the long surviving, complex patterns of Maratha dominance stand challenged in several ways. One, the challenge is of loss of Maratha hegemony and consequent loss of leadership of the non-Maratha backward communities, the OBCs. The other challenge pertains to the inability of different factions of Marathas to negotiate peace and ensure their combined domination through power sharing. And the third was the internal crisis of disconnect between political elite and the Maratha community which further contribute to the loss of hegemony. Various consequences emerged from these crises. One was simply the dispersal of the Maratha elite across different parties. The other was the increased competitiveness of politics in the state and the decline of not only the Congress system, but of the Congress party in Maharashtra. The third was a growing chasm within the community between the neo-rich and the newly impoverished. -

Question Bank Semester VI TYBA Political Science Paper 6- Determinants of Politics of Maharashtra

Question Bank Semester VI TYBA Political Science Paper 6- Determinants of Politics of Maharashtra 1. The relationship between business class and politics exist: A) Even before independence B) Only after independence C) Only after 1970s D) Only after 1990s 2. The link of the Indian chamber of commerce with the Indian National Congress data back to: A) 1940 B) 1920 C) 1930 D) 1907 3. Which of the following business house had intimate relationship with congress in the pre-independence days? A) Birla B) Ambani C) Adani D) Pendharkar 4. One of the highly industrialized state of India is : A) West Bengal B) Bihar C) Manipur D) Maharashtra 5. The commercial capital of India is: A) Delhi B) Mumbai C) Bangalore D) Kokatta 6. Which of the following state is famous for sugar factories? A) Manipur B) Maharashtra C) Bihar D) Tamil Nadu 7. The business class is regarded as which of the following? A) Religious interest gr B) Social interest gr C) Institutional interest gr. D) Cultural interest gr. 8. The interface between politics and business began to develop with A) First 5 year plan B) Second 5 year plan C) Third 5 year plan D) Fourth 5 year plan 9. After independence this plan was heavily industry oriented A) First plan B) Second plan C) Third plan D) Fourth plan 10. The association of business class are called as A) Forum of commerce B) Platform of commerce C) Congress of commerce D) Chambers of commerce 11. The Bombay Chamber of Commerce was organised on as early as in A) 1836 B) 1818 C) 1840 D) 1850 12. -

Questions & Solutions

ENGLISH NDA-2012 EXAMINATION CAREER POINT QUESTIONS & SOLUTIONS PART – A Direction (For the next 08 items which follow) : Read the following 02 passages and answer the questions that following each passage : Passage – 1 There was a farewell ceremony on here day at school, to which my parents and I were invited. It was a touching ceremony in a solemn kind of way. The City Corporation sent a representative and so did the two main political parties. There were many speeches and my grandmother was garlanded by a girl from every class. Then the haed-girl, a particular favourite of hers, unveiled the farewell present the girls had bought for her by subscription. It was a large marble model of the Taj Mahal; it had a bulb inside and could be lit up like a table lamp. My grandmother made a speech too, but she couldn't finish it properly, for she began to cry before she got to the end of it and to stop to wipe away her tears. I turned away when she began dabbing at her eyes with a huge green handkerchief and discovered, to my surprise, that many of the girls sitting around me were wiping their green hankerchief and discovered, to my surprise. that many of the girls sitting around me were wiping their eyes too. I was very jealous. I remember. I had always taken it for granted that it was my own special right to love her ; I did know how to cope with the discovery that my right had been infringed by a whole school. -

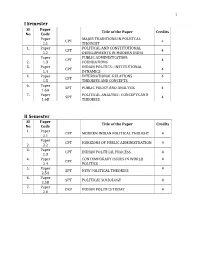

I Semester II Semester

1 I Semester Sl Paper Title of the Paper Credits No Code Paper MAJOR TRADITIONS IN POLIITCAL CPT 4 1.1 THOUGHT 1. Paper POLITICAL AND CONSTITUTIONAL CPT 4 1.2 DEVELOPMENTS IN MODERN INDIA Paper PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION: CPT 4 2. 1.3 FOUNDATIONS 3. Paper INDIAN POLITICS : INSTITUTIONAL CPT 4 1.4 DYNAMICS 4. Paper INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS : 4 CPT 1.5 THEORIES AND CONCEPTS 6. Paper SPT PUBLIC POLICY AND ANALYSIS 4 1.6A 7. Paper POLITICAL ANALYSIS : CONCEPTS AND SPT 4 1.6B THEORIES II Semester Sl Paper Title of the Paper Credits No Code 1. Paper CPT MODERN INDIAN POLITICAL THOUGHT 4 2.1 Paper CPT HORIZONS OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION 4 2. 2.2 3. Paper CPT INDIAN POLITICAL PROCESS 4 2.3 4. Paper CONTEMPORARY ISSUES IN WORLD 4 CPT 2.4 POLITICS 5. Paper 4 SPT NEW POLITICAL THEORIES 2.5A 6. Paper SPT POLITICAL SOCIOLOGY 4 2.5B 7. Paper OEP INDIAN POLITICS TODAY 4 2.6 III Semester Sl Paper Title of the Paper Credits No Code 1. Paper DEBATES IN CONTEMPORARY POLITICAL 4 CPT 3.1 THEORY Paper CPT PUBLIC GOVERNANCE 4 2. 3.2 3. Paper DIMENSIONS OF DEVELOPMENT IN CPT 4 3.3 KARNATAKA 4. Paper 4 CPT RESEARCH METHODS IN SOCIAL SCIENCE 3.4 5. Paper 4 SPT RURAL GOVERNANCE IN INDIA 3.5A 6. Paper SPT GLOBAL CHALLENGES 4 3.5B 7. Paper OEP HUMAN RIGHTS : ISSUES AND CHALLENGES 4 3.6 IV Semester Sl Paper Title of the Paper Credits No Code 1. Paper MODERN WESTERN POLITICAL CPT 4 4.1 THOUGHT Paper GOVERNMENT AND POLITICS IN CPT 4 2. -

India: the Shiv Sena, Including the Group's Activities and Areas Of

Home > Research > Responses to Information Requests RESPONSES TO INFORMATION REQUESTS (RIRs) New Search | About RIRs | Help 29 April 2011 IND103728.E India: The Shiv Sena, including the group's activities and areas of operation within India; whether the Shiv Sena is involved in criminal activity; if so, the nature of these activities (2009 - March 2011) Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Ottawa The Political Party The Shiv Sena, a political party in the Indian state of Maharashtra, was formed in 1966 and is led by Balashaheb Thackeray (Political Handbook of the World 2011, 632; MaharashtraPoliticalParties.com n.d.a). Other party leaders, according to the Political Handbook of the World 2011, include Uddhav Thackeray, the party's executive president, and Anant Gheete, a leader in the Lok Sabha (2011, 632). The Lok Sabha (House of the People) is a unit of the national Parliament, along with the Rajya Sabha (Council of States) (India 16 Sept. 2010). Members of the Lok Sabha are directly elected by eligible voters every five years (ibid.). In 2009, the Shiv Sena won 11 seats in a general election (Political Handbook of the World 2011, 632). The Political Handbook of the World notes that Shiv Sena is "closely linked" to the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) (2011, 632). The Press Trust of India (PTI) reports that on 6 March 2011, the BJP leader "said his party's alliance with Shiv Sena will remain intact at [the] Maharashtra and national level" (6 Mar. 2011). In 14 April 2011 correspondence with the Research Directorate, an honorary senior fellow and chairman of the Centre for Multilevel Federalism, at the Institute of Social Sciences in New Delhi, noted that the Shiv Sena was "the main opposition party" in the Maharashtra legislative assembly of 2004 to 2009. -

TERRORISM, COMMUNAL POLITICS and ETHNIC DEMOGRAPHY: IS THERE a CAUSAL CONNECTION? Empirical Analysis of Terrorist Incidents in Maharashtra

M. Mayilvaganan TERRORISM, COMMUNAL POLITICS AND ETHNIC DEMOGRAPHY: IS THERE A CAUSAL CONNECTION? Empirical Analysis of Terrorist Incidents in Maharashtra May 2020 International Strategic and Security1 Studies Programme National Institute of Advanced Studies Bengaluru, India Research Report NIAS/CSS/ISSSP/U/RR/08/2020 TERRORISM, COMMUNAL POLITICS AND ETHNIC DEMOGRAPHY: IS THERE A CAUSAL CONNECTION? Empirical Analysis of Terrorist Incidents in Maharashtra National Institute of Advanced Studies Bengaluru, India 2020 © National Institute of Advanced Studies, 2020 Published by National Institute of Advanced Studies Indian Institute of Science Campus Bengaluru – 560012 Tel: 22185000, Fax: 22185028 Email: [email protected] NIAS Report: NIAS/CSS/ISSSP/U/RR/08/2020 ISBN 978-93-83566-38-9 Content Introduction .............................................................................. 1 India and Terrorism .................................................................. 7 Maharashtra ............................................................................ 8 Micro Level Analysis ................................................................. 10 Key Observations ..................................................................... 24 Inference ................................................................................. 26 INTRODUCTION Is there a causal link between ethnic demography, communal violence, local politics and terrorism? What factors might prompt a terrorist to choose a target place? Why the states like Maharashtra